Photo: Tamar Levine

Deftones

news

20 Years After 'White Pony', Deftones' Chino Moreno Is At His Most Vulnerable On 'Ohms'

The renowned rock frontman talks to GRAMMY.com about opening up on Deftones' ninth studio album, how isolation is treating him, 20 years of 'White Pony' and more

The year 2000 feels like a lifetime ago for Chino Moreno, frontman of Deftones. The year that birthed the Sacramento alt-metal luminaries' most commercially successful album, White Pony, no doubt is a long time ago, but 2020's pandemic—combined with hurricanes, wildfires, racial reckonings, a heated presidential election (just to name a few)—makes the new millennium feel like more like a century ago. Looking back on the band's third album, Moreno is reflective regarding their sound's longevity. "It's a trip, man," he says on the phone from Portland, Oregon. "It seems like forever ago, and I guess it kind of was in a way, but it's awesome that that record still carries so much weight to it."

A band that formed in the late '80s, Deftones have developed a catalog that blends nu-metal, hard rock and synth sounds with anything else that tickles their fancy. They are experts at crafting a soundscape that introduces hard and heavy guitar and drums to softened undertones. It's all married by Moreno's vocals, which can go from croon to shriek. And they're still standing the test of time. This year, 20 years after White Pony's release, Deftones find themselves days away from releasing their ninth studio album, Ohms, out Sept. 25.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed/KUDbj0oeAj0' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

At a time where every day takes us even more into the unknown, Ohms, packed with the familiar heaviness (in both sound and lyricism) will come as a comfort to fans. But this time, their music won't serve as escapism; it's more grounding than ever.

Despite the familiarity, Moreno finds himself in new territory. He is more open, more vulnerable than ever, he explains: "Usually, I steer away from [vulnerability] a little bit. I think it was just like the music itself. I connected with it in a way where it was calling for that."

Moreno recently spoke with GRAMMY.com about opening up on Ohms, going into isolation during the making of the album and how he feels about isolation now. He also covers painting with words via songwriting, connecting to his Latinx fans, taking a risk with White Pony and more

You're releasing your first album in four years. How are you feeling?

Pretty excited. I mean, obviously it's a little different than what we're used to, usually at this time we'd be on tour, out ready to support the record itself. Yeah, it's a little different, but actually it's been good for us to have something to focus on in these times of uncertainty. It makes you feel a little normal, just being able to put the finishing touches on it and put it out there and hopefully have people enjoy it.

The album has a very familiar sound, but it hits different right now with everything going on. It makes you feel present instead of trying to escape reality. Do you mind that?

No, not really. Music has always kind of been about escape for me in a way, but I feel like lately, and probably, like you said, a little bit more with this record, it kind of feels a little more present. I sort of opened up a little bit more on the record. There's still some anonymity there. It's still doesn't feel like it's just this direct message. I let some more of my, I don't know, just my personal vibes into it. Usually, I steer away from that a little bit. I think it was just the music itself really. I just connected with it in a way where it was kind of calling for that. I think the songs kind of had this tension to them that brought that out of my lyrics and my vocal performances.

Is it freeing for you being able to do that on this album?

I don't know if it's freeing. It's still a little scary. Honestly, it's not the most comfortable thing. I always had a hard time writing lyrics and communicating and being direct. It's just with a lot of the records that I even like, too, I usually gravitate towards things that are a little bit more obscure. So when I'm making music, I tend to lean that way. But even with this, it still has that kind of obscurity to it, whatever. But I think certain things bleed through a little bit more. And it's weird because a lot of the record itself was actually written and recorded mostly before everything that's been going on in the last six months or so. But it's weird and ironic how it's very... it sort of mirrors kind of what's going on. Not the whole thing, obviously in general, but I feel like a lot of things that [are] reoccurring in the record are very bearing to current times.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//fbp0bET06wc' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

"Ohms" means a unit of electrical resistance. After hearing you talk about how were able to open up a little bit more, I'm wondering if you're resisting something else on the album?

No. I think it's also about connection.

I think that really rears its head a lot in a lot of the words of the record. For me personally, I was dealing with a lot of feelings of isolation and working through all that stuff. And that was like a physical thing of me just sort of being away from everybody for a long time. I'd spent about five or six years living out in the country, away from all my friends and all the people that I've made music with. Before that, I was living in Los Angeles. I was always around music or my friends who make music and I was constantly always filling that creative void. When I went on my own, I was like, "Okay, well, I'm just going to sit here and I'm going to make a bunch of music and I didn't make any music." I literally just—I'd go out to the mountains by myself and I'd hang out, and I liked it at first. But there was no balance there. At some point, I started to long for connection and conversations and just being a part of society again.

And so a lot of that stuff made its way into the lyrical content of the record. And like I said, the songs themselves kind of had that feeling to them. So with the title, it's obviously hard to title, to have one thing [encompass it all] because the record is not a concept record in any way. So it's hard to just think of a name that's going to blanket the whole... There's no statement there, or anything like that. I just felt like it really made sense. I mean, there's obviously this resistance and creating energy amongst the five of us as well. We were all sort of polarized in the way that we work. Everybody comes from a different place and I think that's what makes Deftones. It's kind of a beautiful thing in a way because if we all came from the same place, I think our music would suffer from being too one-dimensional. As to where there's a lot of push and pull involved in the songs themselves, so I think that's kind of always been one of our strong points.

Your title track was inspired by the environment. Tell us how.

Basically the state of the environment now. It was kind of literal when it came out, but then I realized that whether the song could be adapted obviously to a relationship, or whatever, where you are today is pretty much because of all the choices you've made coming through. So like I said, the very first adolescent mind in me just said, oh, this is definitely—and I never really write songs specifically about one thing—I like to keep it open-ended like that. But when a lot of people were, you know, because everybody has a different—it means something different to them. So I left it open-ended enough as it is.

But yeah, to answer the question, when they asked me like, "What did you write the song about?" That was, honestly, the first thing that clicked in my head. But then it very much opened up to a much broader spectrum.

I want to get into the lyrics a little bit. You write, "Through the haunted maze in your eyes, right through where I'll remain for all time." This could be in a poetry book. Are you inspired by any poets or writers at all?

You know what? When I was younger, like maybe a teenager, I think all teenagers get into this romantic phase. I used to try [to write poetry], but it used to always come out pretty hokey. My vocabulary is not that huge. I only have a high school education. But my favorite class that I did have in high school was creative writing, so I've always liked to kind of paint with words. And I feel like I've done that in a lot of our records, some more than others, but I don't really read books of poetry. I'm not really... I love music and I love when artists, when they paint pictures with their vocals. There's a vibe that's kind of given off and then the words fill in these gaps and it's not just like such a literal thing. Then, like I said earlier, you make your own interpretation of it and it kind of makes it special to you.

Your music puts together very heavy sounds with these subdued, rich undertones. Did you always set out to do that with your music?

I don't think it was something that was intentional or preconceived in any way. I think it was just what we grew up listening to individually and collectively. I've never felt comfortable with fitting in any one box, even from when I was young. In high school I hung out with everybody. I hung out with the goth kids. I was a skater, but I hung out with the preppy kids who listened to Pink Floyd and just everything. Some of the rap kids, everything. I listened to everything growing up and I never felt comfortable just having to pick a music that I was going to make, or at least that I was going to like even at that time. But especially when we're making music, We all continue on with that thought. I mean, yes, I think we are a rock band, you know what I mean? And the majority of it does have these heavy undertones, but to just box ourselves into that, I have never felt comfortable. So I feel like we've always drawn from influences from all the stuff that we grew up liking and loving.

Some of your fans like to really geek out on your synths on Reddit. How are you incorporating those sounds on this album?

I'm a big fan of a lot of synth music—from my childhood until now. When Frank [Delgado] first came into the fold, he didn't have any instruments and he didn't play any instruments, he was a DJ. So when he started using his turntable, we brought him in to bring in some kind of soundscape and more sample stuff. It wasn't about scratching or to add a hip-hop element at all to the music, he sort of blended. Our idea was to have him blend in where you almost don't know he's there. I feel like with now, even with the synths, although there are more, since he started getting more into instruments and bringing synthesizers into it, I still think that we try to keep that [idea of] mentality it not being [there]. If you hear the first song on the record "Genesis," there are synths present obviously on the intro, but throughout the song as well. Throughout the song when you hear them, they're there but I think we're very cautious of not making them overbearing as well because there's one thing that's important, that is as much as I love synth, they, along with guitar, don't blend well. They do, but if you turn the synth up too much, it takes away from the attack of the guitar. So then it can soften where a song should be heavy, it was written heavy, the synth can take that away from it. So the blend of it has to be right. And so that's kind of the task sometimes. We work hard on that because it's something that we love, but like anything you don't want to overdo it, you want to make it so it sounds organic and not like we shoved it in there just for the sake of doing it.

This is your ninth album. How reflective is it of where you are as a band?

I feel like it's pretty damn reflective. All our records are sort of a snapshot of that time. And obviously some times are better than other times, as far as us and the way that we work together. We've been through some tough times here and there. And I think those records kind of mirror that as well. This record, to me, it sounds very solid to me. If I had to compare it to a lot of our other recordings, I feel like it's a very solid recording. I feel like we spent a good quality of time on it, so I feel like the quality in general is there. Us as a band and as friends, more than anything, we're very engaged and having a really fun time making it. Although it's not like a party record in any way, there were a lot of laughs and a lot of good times making it. I feel like that reflects definitely when you hear the record in its entirety and hear that it's a solid piece of work and not something that was just slapped together at all.

You worked with Terry Date on this and you hadn't worked with him for a minute. How did he help you bring your vision for this album to life?

He's a really great sixth member of the band. We have a very close working relationship with him since the mid '90s when we did our first record with him up through our fourth. And then our sixth record we started with him and we didn't finish it. That was when our bass player was in a car accident, so at that point, we cut the record. We weren't finished with it, but we stopped working on it. When we continued again, we sought out a different producer, not because we didn't want to work with Terry but just because we wanted to start something brand-new from scratch. We felt like that might be the way to go as far as getting us in a whole different city and in a different studio with a different person.

So we did a few records with Nick Raskulinecz, which were great. But I think during that time, we all missed working with Terry just because, like I said, our friendship and our working... what's a good word? The way that we work with him, basically, it's very comfortable in a good way, where it's almost like you can try anything and it's just like there's no getting to know each other and figuring things out. He really is open, he's patient, and gives us space to sort of find our own way through making our songs as opposed to like trying to dictate where things should go. He is the best person I think that brings everything out of... lets everybody be themselves, lets everybody shine, I guess, in the best way, and captures it.

I grew up in L.A. and I remember listening to Deftones on KROQ thinking like, damn, this is such awesome music. And then I found out your name was Chino Moreno, not knowing what you looked like at all, but thinking like, damn, that's dope. That's a name that sounds like mine. Do you ever think about how much something like that might mean to your Latinx fans?

Yeah, I see it. When we travel. I notice we have a big Latin following and it's awesome to see faces, familiar faces, that you don't know, but they look like my brothers and sisters, my cousins, it's awesome. There's this connection that's there, that's just sort of unspoken. But we can go, especially through Texas, it's wild. You can go through there and you see so many just familiar faces and people and you just see just the love that's just like, and the passion really. You know what I mean? From these fans, it's really, it's a beautiful thing.

You recently celebrated 20 years of White Pony. How is it looking back at that album all these years later?

It's a trip, man. It seems like forever ago, and I guess it kind of was in a way, but it's awesome that that record still carries so much weight to it. When we made it, we obviously were taking a chance doing something that was a little different from where contemporary music was, you know? What was being played on the radio or MTV at the time. In our minds, we didn't know that anybody would even like the record. But we definitely were really into what we were doing and we didn't look back. And when it came out, it was sort of a lukewarm response. I mean, a lot of our fans liked it, but a lot of our fans didn't like it. What was crazy is that because they were used to just Deftones [being] in your face 90% of the time, 10% trippy shit. But this was like kind of maybe 50% trippy shit, maybe 50% in your face. So I think they just wanted more aggression from us, and I think we were just in a different place. Some of our fans, I don't think... It grew on them. But some of them just like, yeah, they did not get it.

What was cool is that we gained a bunch of different new fans that just only knew us from that and liked us for [that]. It was their first introduction to us. It's probably our most commercially successful record, and we're very proud of it. I'm happy that it's stood the test of time and people still react to it and are moved by it.

Is there musically something that you haven't done but want to do?

Nothing in particular. I definitely want to continue making music. Like I was saying earlier, I was, for a few years, maybe like six or seven years ago. I was really, really prolific. I was doing a lot of projects, like tons of side projects, along with Deftones, everything. And I was loving it. It was really, really fun, but it was when I lived in L.A. and I was surrounded by all my friends and musicians all the time. It was like it was just a natural thing. Then I stopped I stopped making music for awhile. I did one Deftones record, and that's about it really, in the last four years or so besides this Deftones record. So I'm looking forward to start doing more projects, collaborating with different people. That's really fun for me. And that's kind of one of the best ways I like making music is collaborating as opposed to just making music by myself. I love reacting to what someone else is playing and going back and forth, to me that's really, really fun. So I look forward to doing more of that.

Earlier you mentioned during the process of making some of these songs, you went off to the country and you felt isolated. How have you been doing with the isolation the pandemic has brought?

It's tough. I have two older sons who are in their 20s who I haven't seen. They live in Sacramento. I live in Oregon right now, in Portland. I was with them maybe two weeks before the shutdown happened. I went down there and stayed for like a week. My mom and my dad both live down there too, so all my brothers and sisters. I was seeing my whole family. Since the shutdown, I haven't gone, I haven't been able to see them. I get in like these little—and I'm sure a lot of people deal with this so I'm not saying "poor me" because I know everybody's in the same boat now—but yeah, I miss them and I want to spend time with them. But everything's very delicate still, so it's a difficult thing to do, but I plan on, in the next couple of weeks, doing that. So I have something to look forward to. I just try to keep optimistic and positive about it.

Doves On Their First Album In A Decade & Why They’re Still Trying To Stay Patient

Photo: Robby Klein

interview

HARDY On New Album 'Quit!!' & How "Trying To Push My Own Boundaries" Has Paid Off

On his third album, the self-described "black sheep" of country music proves he's here to stay.

Haters take note: nothing fires up a country boy like HARDY more than a naysayer. And this redneck has a long memory.

Despite the coveted catalog of country music hits to his credit — tunes he wrote for artists like Florida Georgia Line, Blake Shelton and Morgan Wallen, plus his own work as a solo artist — HARDY's third album begins with a three-minute response to a heckler who once left a nasty note in his jar in place of a tip.

That moment may have occurred a decade ago, but it's key to HARDY's defiant persona. In fact, the album's title is exactly what that note read — Quit!! — and its cover art is the actual napkin the message was written on, which the singer/songwriter has held on to all these years.

HARDY laughs off the memory at first, but as the title track plays on, his olive branch soon turns to coal. "I'm not the GOAT, I'm the black sheep hell-bent to find closure," he barks as the song escalates. "I can't let go — a note somebody wrote like ten years ago put a chip on my shoulder. If you wanted me to quit, you should've saved it, bro."

The takeaway here? HARDY won't quit. Or, to quote another Quit!! banger, "I DON'T MISS," when a hit is in the crosshairs, he "don't hit nothing but the bull's eye."

No doubt, he has the numbers to back it up. HARDY linked up with Florida Georgia Line after moving to Nashville in the 2010s, and landed his first country No. 1 as a songwriter in 2018 thanks to the duo and Wallen, with the smash "Up Down." As he began building a solo career — releasing a pair of EPs in 2018 (This Ole Boy) and 2019 (Where to Find Me) — he continued delivering chart-topping hits for FGL, Shelton, LOCASH, Wallen, Dierks Bentley, and more. As Quit!! arrives, HARDY boasts 15 No. 1 hits: 11 as a songwriter, and four as an artist.

Along the way, HARDY also established his Hixtape series, a countrified version of a hip-hop mixtape now three volumes deep, bringing together friends and superstars like Keith Urban, Trace Adkins, Thomas Rhett and a host of other stars to collaborate. Not only did Hixtape Vol. 1 land HARDY his first No. 1 as an artist in his own right — the Lauren Alaina and Devin Dawson team-up "ONE BEER" — but it put HARDY's shapeshifting musicality front and center.

"A lot of people ask, 'When did you decide to jump into the rock and roll thing?' HARDY, who uses his last name as his stage name, says. "I feel like I've always dipped my toes in it here and there, and a lot of my songs have been really close to it but not quite there. Hixtape, especially Vol. 1, I was definitely foreshadowing my sound, and I really didn't even know it at the time."

By now, modern country musicians regularly reflect influences from beyond Nashville's confines. But HARDY has played a big role in rock's country crossover, as he gradually showed more of his Mississippi-bred, guitar-riffing roots on his 2020 debut album, A ROCK. He fully embraced them on the 2023 double album, the mockingbird & THE CROW; while the first half has more country-oriented tunes like the Lainey Wilson-featuring murder ballad "wait in the truck," he lets loose on THE CROW.

"THE CROW will always be that cornerstone moment that defined who I am," he asserts. "It gave me the courage to do this Quit!! record."

HARDY has not only been an architect of this genre blending, but also its chief proponent — so much that in 2023, the L.A. Times crowned him "Nashville's nu-metal king." On Quit!!, he cashes in that currency with the gargantuan guitar riffs and bombastic beats popularized by acts like Limp Bizkit, and leans deeper into the rhythms and playful lyricism of hip-hop, a skill he recently flexed at the request of Jimmy Iovine and Dr. Dre on a hicked-up rendition of Snoop Dogg's G-funk classic "Gin and Juice."

Ironically, the further HARDY gets from straightforward country music, the closer he gets to who he really is as an artist. Below, the chart-topping star details the backstory of Quit!!, his conflicted relationship with the country-music formula, and how he'll continue pushing boundaries within the genre and beyond.

You grew up in the small town of Philadelphia, Mississippi. What role did music play in your upbringing?

My dad introduced me to rock and roll in general, but it was his era of rock and roll. Whatever you define as classic rock and everything under that umbrella. But music was a big deal in Philadelphia and it still is. There were tons of cover bands, and a lot of [my] buddies were into music. So that had a big influence on me.

I, thankfully, was in that last era of kids that the only time they got to hear a song was on MTV or on the radio. And I remember hearing "In the End" [by] Linkin Park, and then getting Hybrid Theory on CD. I remember the first time I saw [Limp Bizkit's] "Nookie" video on MTV. I was heavily influenced by all that stuff. I'm very thankful that I grew up in the era before the internet was really big.

Were you into country music back then?

Surprisingly, not at all. Not until Eric Church, Brad Paisley, a couple of people started singing about stuff that really piqued my interest. But no, I didn't really listen to much country.

I think the only country that I listened to, if you even call it that, was Charlie Daniels. He played at the Neshoba County Fair. I got to see him twice. But even he was more of, like, you'd almost call it more Southern rock. For some reason, country music at the time didn't do it for me. It took me a long time to get into it.

You recently re-envisioned "Gin and Juice." Were Snoop Dogg and Dr. Dre big artists for you when you were younger?

Yeah, especially Snoop. Snoop was in his later years when he started doing more pop stuff. I was a little too young for Doggystyle. I was 4 years old when Doggystyle came out, so my folks weren't letting me listen to that. But I will say, [Dr. Dre's 1992 album] The Chronic and especially [1999's] Chronic II, those records were huge. And anything that Dre touched after that, like all the beats he produced for 50 Cent, and obviously I'm a huge Eminem fan. I mean, all the way up to Kendrick [Lamar]'s early stuff.

I don't know how much they influenced me musically, but I definitely listened to both of them at the time.

You've got so many projects and co-writes and stuff going on, always. Is it easy to pinpoint where your journey to Quit!! began?

I can tell you for a stone-cold fact that "BOOTS" [from A ROCK] is responsible for the album Quit!! That was the first song that I ever wrote that had a breakdown in it. And when I played that live before it came out, people didn't know it, so it was a little different then. But once the song came out, and we started playing it live, it was bigger than "ONE BEER." It was bigger than "REDNECKER." It was the biggest song in our set, and to this day, it's still one of the biggest songs in the set.

But because I love the rock and roll sound so much, that's the song that I was like, Okay, this is working, because these people are losing their s— when we go into this song. So, then, that inspired me to write "SOLD OUT," and once "SOLD OUT" came out, and we started playing that song, that song was even bigger than "BOOTS," and it was heavier than "BOOTS." After "SOLD OUT," it was "JACK," and it's just a snowball of writing heavier songs and having the courage to keep going. "BOOTS" crawled so that Quit!! could run, you know? That was definitely the song that started it all.

The new album builds on the mockingbird & THE CROW and the direction you were heading.

Yeah, I think it builds on it maybe in the sense that there's a lot more screams, and maybe more breakdowns, and it's a little heavier than the mockingbird & THE CROW at times. But it is also very different. There's a lot more, like, pop-punk stuff and, I don't even know what you would call it, post-hardcore-sounding s—.

But all of the rock and roll stuff stands on the shoulders of THE CROW. It will always be that cornerstone moment that defined who I am. I mean, it definitely teed me up. It gave me the courage to do this Quit!! record.

I like that word, courage. It's not a word I expected to hear out of you based on your persona, but that's a very interesting way to phrase it.

No, I mean, the metal and country cultures are very, very, very different. There's never fear, but there's definitely, what's the right way to say that? You know, there's like when we throw like the goat horns and s— on the screen. Country has a big Christian background, and metal is like the exact opposite of that, and those can clash a lot, but there's definitely a little bit of some reserve — it seems to not get too much push back — mixing the two. My mom's not crazy about it, but what can you do?

And you have moments like "wait in the truck," where you're not writing for the party. Do you see yourself pursuing those avenues more often? Does the world want to hear HARDY reflect?

You mean like more of the deeper country stuff?

Correct, yeah.

I hope. That's the s— I love. I feel like they're so few and far between. Like, "wait in the truck," we just got so lucky. I feel like "ONE BEER" was kind of the same. Like, it's gotta be the right day, and the right time, and the right people in the room to really tell a story. It's tough. But I would love to continue to have those cool story songs.

But what I will say is there's a lot of gray area between the black-and-white of HARDY country and HARDY rock and roll. I'm still going to put out country songs. The gray area is that to me and to a lot of people, they're all just HARDY songs. But I have so many songs that I have written that I wanna put out that are so, maybe if they're not storylines, they're even deeper down the rabbit hole of thought-provoking stuff, like "A ROCK," or maybe even "wait in the truck," or even a song I have called "happy," on the last record — just songs that are very, very thought-provoking.

Just trying to push my own boundaries of country music, and not everything is right down the gut, you know, "let's go to radio with it." But just really trying to experiment with what I wanna say with country music. So, yes, there's definitely more of that coming.

You're playing your first headlining stadium gig in September. How has performing in those venues, and anticipating that, informed how you write? Are you writing for the stage?

Yeah, 100 percent. I would say, 75 percent of the time you're writing for the stage — even if it's not for myself, if I'm writing for somebody else — I'm definitely writing for the stage. I cannot tell you how many times I've sat in the room and been like, This s— is going to pop off live! And then try to put the other writers in that headspace.

Like on [Quit!! track] "JIM BOB," when we did the pow-pow-pow! thing, I'm like, just think about how cool it's gonna be live, and living in that headspace, because that's where it all comes to life. That's the end product.

Writing for the stage is something that a lot of people do. And that's why songwriters love going out on the road, is because they go out and they write songs with these artists, but they love watching the show because they get to see what really translates live, and then take that back to the writing room and try to recreate that.

Did that kind of experience have anything to do with you making the move to a marquee artist? Because not all songwriters can make that jump. Or was that always the plan?

Yeah, I mean, it was always that kind of thing. I was fortunate that I got to see Morgan [Wallen] perform "Up Down," and FGL perform a couple of their songs before I made the jump into an artist. I kind of already scratched that itch a little bit.

The Nashville writing scene can seem like a 9-to-5 kind of boring thing. But it doesn't sound that way from the way you describe it.

It's a little bit of both. The funny thing about that is like, if you walk into a publishing company, 10:30, 11 o'clock, whenever people start getting there, it's a bunch of dudes or girls standing around drinking coffee, hanging out. It's like a break room, and then everybody's like, "All right, well, y'all get a good one." And then everybody goes into their own rooms. That part of it is very 9 to 5.

But there is definitely — especially with our group of people, when you get on something that is so special, it's beyond, like, "We're writing a hit today." There's just something that transcends that. I don't know how to describe it, man. That's when it's really, really, really, really great. The Nashville process, that's what it's all about — having those moments in the room where you're like, "This is special," and, like, "We're witnessing something special that is going to affect people on a global or on a nationwide scale."

I remember when we wrote "wait In the truck" and how we were all just gassing each other up because we were like, "Dude, this song is gonna help a lot of people." And that's when the 9 to 5 goes away. We're being creative together, and it's a special thing.

There's been so many moments like that, where you're just so thankful to be a part of a great song, and how hyped everybody is. It's a feeling that's really, really hard to beat.

More Of The Latest Country News & Music

HARDY On New Album 'Quit!!' & How "Trying To Push My Own Boundaries" Has Paid Off

Amy Grant Shares Where She Keeps Her GRAMMYs

Watch Tiera Kennedy Perform "I Ain’t A Cowgirl"

How 'Petty Country: A Country Music Celebration' Makes Tom Petty A Posthumous Crossover Sensation

Vince Gill Reveals Where He Keeps His GRAMMYs

Photo: Rich Fury

list

A Beginner’s Guide To Phish: 8 Ways To Get Into The Popular Jam Band

Not a Phish phan? No worries. Ahead of their 26-date tour and new album, 'Evolve,' dig into this primer on the music and the subculture of the most popular jam band since the Grateful Dead.

Mainstream rock or pop, Phish are not. While the foursome from Vermont are definitely a jam band, that label does not capture their unique sound and varied influences. Both on record and live, Phish's extended improvisations noodle from reggae and all forms of rock, to bluegrass and funk, with healthy doses of country, blues and jazz.

Like the jam band godfathers the Grateful Dead, Phish built its devoted fanbase not through singles and airplay, but via tireless touring and word of mouth. On some nights — okay most nights — even the band has no clue where their rambling live shows will go. This spontaneity has been Phish's guiding ideology from its earliest days playing college campuses to their annual residency at Madison Square Garden; there is nothing contrived or calculated about a Phish show; instead, the band's filled with surprises and set lists that change more frequently than you change your bedsheets.

For more than 35 years now these four souls have been taking Phish-heads along on this joyous musical ride to unknown soundscapes. Concerts are fueled by passion, not perfection. Ask 10 Phish phans what their favorite live show is from the band’s history and likely each will offer a different answer and argue the reasons for their choice as if it were a thesis defense.

Read more: A Beginner’s Guide To The Grateful Dead: 5 Ways To Get Into The Legendary Jam Band

For Phish, it’s not about awards and accolades. The group has just one GRAMMY nomination and its highest charting single came and record came 30 years ago. In 1994, Billy Breathes peaked at No. 7 on the Billboard 200; its lead single "Free" hit No. 24 on the Billboard Hot Modern Rock charts and No. 11 on the Mainstream Rock Tracks chart.

What attracts people to Phish's music and subculture is the mood, the groove and the community; that’s why the band perennially have been one of the highest grossing live acts throughout their career. The band is also part of American pop culture: They have a Ben & Jerry’s flavor (Phish food), have appeared on "The Simpsons" and been parodied on "South Park."

This spring, Phish became only the second band (after U2) to perform at the Sphere in Las Vegas. Over the weekend of April 20, the foursome played four shows with a completely different set each night. The final show on Sunday evening featured an epic second set, even by Phish standards: the band performed for nearly two hours and jammed on for 34-minutes on "Down with Disease."

Surprises like this musical meandering abound at Phish shows and it’s another reason fans shell out a hefty chunk of their pay cheques to see them live again and again and again; it’s also what makes attending one of their concerts a unique experience. The relationship between the band and these devotees is symbiotic. Both inspire and guide the other.

Phish does not take itself too seriously. This is reflected in their songs, their artistic approach and their love of a good prank. Ready to go Phishing? Not the dictionary adjective that conjures negative connotations of scams and identity theft, but rather, a new word we suggest adding to the Urban Dictionary meaning to take a deep dive into the weird and wonderful world of Phish.

In advance of the band’s 26-date tour that starts with a three-night run in Mansfield, Massachusetts to promote Evolve — its 16th studio record that arrives July 12 — GRAMMY.com offers a lowdown on these musical merrymakers. Read on for a guide to appreciating and approaching Phish's lingo, lore, and lengthy discography.

Phish 101

Before the band had a name, a following, or conferences and university courses dedicated to the study of their music, they were just a bunch of college kids jamming in their dorm. The original members of the band met while attending the University of Vermont in Burlington. Initially formed as a trio in 1983 that featured guitarists Trey Anastasio and Jeff Holdsworth, along with drummer Jon Fishman. Bassist Mike Gordon joined that fall. In 1985, keyboardist Page McConnell was added and Holdsworth left. Today, it's these four (Anastasio, Gordon, Fishman and McConnell) that comprise Phish.

Junta, the band’s self-released debut arrived on cassette in 1989, followed by Lawn Boy the next year on Absolute A Go Go Records. The industry buzz created by their live shows then led to a multi-album deal with Elektra Records, who, in 1992, released their major label debut A Picture of Nectar, along with reissues of Junta and Lawn Boy.

What’s with the name? Everyone loves a good band name origin story, and there are often several versions of Phish's. The simplest and most popular one cited is that Fishman was asked at an early gig for the band’s name and thought they were asking for his name, so replied with his college nickname, "Fish." It stuck and they just changed the spelling.

A Lesson In Lingo: 4 Phish Phrases

Next up on the Phish syllabus is a lingo lesson in lingo. Overhear a pair of Phish fanatics chatting in a coffee shop, and you’ll wonder if they are speaking a different language. These devotees have developed their own lingo to express their love for all things Phish. Here’s a quick primer to help you converse with phans as if you know what you are talking about.

First, phans label each era of the band a number and these labels describe when their love of Phish began: 1.0 refers to the band’s beginnings until its first break in 2000; 2.0 is a short period and a small cohort of fans that starts when Phish returned from its first hiatus in 2002 and ends before they officially broke up in 2004. Finally, 3.0 refers to new converts: fans who discovered the band only after they reunited for good in 2009.

As this schooling on Phish continues, here are four words to drop into a conversation with a Phish fan to make you sound educated. "Noob" is a condescending word referring to a newbie, like post-2009 phans. A "chomper" is someone who talks during songs at a Phish concert (definitely a no-no). "Spunion" is someone whose appearance, actions and speech indicate they’ve taken way too many drugs. Finally, "hose" is a free-flowing improvisational jam where the music feels like it just flows directly into the listener’s ears.

Down On The Farm: Hits & A Few Phan Favorites

From the 2000 record of the same name, "Farmhouse" is one of the few Phish songs that made a splash beyond just their fans thanks to this radio-friendly chorus: "I never ever saw the Northern lights/I never really heard of cluster flies/ I never ever saw the stars so bright/ In the farmhouse, things will be alright." Besides this earworm, the ninth record from the band also featured another one of its biggest charting radio hits: "Heavy Things," which reached No. 29 on Billboard’s Adult Top 40 chart and No. 2 on the Adult Alternative Songs charts.

Some other key studio tracks to explore and listen to that show the depth and breadth of the band’s talents include: "Golgi Apparatus," "Chalkdust," "Torture," "Sample in a Jar," "Character Zero" and "Sand."

Into The Studio: A Choice Phish Records

Phish have released 20 studio albums and 53 live records. That’s a lot of music to sift through for any newbie. Three key albums to help understand and get into the band include: A Picture of Nectar (their major-label debut from 1992 that was certified gold), Hoist (1994) and The Story of the Ghost (1998), recorded at famed Bearsville Studios in in Woodstock, NY - a record Trey Anastasio described as "cow-funk." Listen carefully to this trio of records and you’ll come away from these deep dives either loving the band and ready to take the next step on this phishing trip or not.

Make sure to also check out the conceptual album Rift. This follow-up to their major-label debut is a fan favorite and also a critical darling. It’s possibly the band’s greatest studio creation, but it’s also an acquired taste. Rift follows the story of a man who dreams about the rift in his relationship with his girlfriend. The listener follows this protagonist on a dark and heavy ride as his emotional journey turns from a pleasant dream to a nightmare. The narrative is told backed by a sonic palette that showcases all of Phish’ colors and musical influences: from jazz and blues to psychedelic rock and funk.

Go See Phish Live

As Neil Young sang in "Union Man," that is often-quoted by concert lovers, "live music is better bumper stickers should be issued." Phish subscribe to this mantra and are known to plaster their cars in bumper stickers. The centerpiece of a Phish show is extended jams and the communion between Phish fans, but their concerts also feature amazing light shows, props, and pranks.

To get a sense of what attending a Phish concert is like, start with the six-disc set Hampton Comes Alive. Released Nov. 23, 1999, the collection consists of two concerts in their entirety captured at the Hampton Coliseum in Hampton, Virginia in 1998. The title plays on Frampton Comes Alive! — one of the best-selling live albums of all time.

In the band’s early days before the Internet came of age, bootleg tapes abounded. Trading these — just like Grateful Dead fans do — was always a part of Phish culture. LivePhish captured all of the band’s live shows. This is now an Android app where you can stream shows, past and present. Mere minutes after each Phish concert ends, the newest show is uploaded.

Before the streaming age, the band frequently released CDs up to six discs in length (most Phish concerts run more than three hours). One of these essential listening live releases is Darien Lake from Sept. 14, 2000 that includes a cover of Neil Young’s "Albuquerque."

Order Up The Baker’s Dozen

For Phish fans, the 13 concerts dubbed The Baker’s Dozen are pure bliss. The residency occurred at the Manhattan mecca from July 21 to Aug. 6, 2017. Every night featured a different set list (26 total sets as they played two each night). No song was repeated and each night had a theme.

Over the course of 13 shows, Phish played 237 songs. A highlight of The Baker’s Dozen was a 30-minute jam of "Lawn Boy" — a song that usually clocks in under four minutes.

Cover Me

Many consider the group the greatest cover band on earth, so go down the Phish YouTube rabbit hole and what matters at this moment in your life is sure to get neglected for a while.

An understanding of Phish's many collaborations and covers tis also essential to better appreciate the band. Phish has paid homage to everyone from classic rockers like Lynyrd Skynyrd, ZZ Top, Led Zeppelin and the Rolling Stones, to Frank Zappa and the Talking Heads. Collabs include: Bruce Springsteen, Neil Young, and weird as it sounds, even Jay-Z, who the band invited on stage during a Brooklyn gig in 2004, to sing-along on the 24-time GRAMMY-winner’s hits: "99 Problems" and "Big Pimpin.’"

Trick Or Treat Tributes & Auld Lang Syne Shenanigans

Halloween shows always feature musical costumes where Phish plays another artist’s album from front to back. The Beatles' White Album in 1994 is especially good and the first time the band premiered this concept. Many fans claim the 1998 Halloween show where the band covered the Velvet Underground’s Loaded is one of the most underrated and was mind blowing. But the best might be from 2018 when they invented a fake Scandinavian synth-rock outfit called Kasvot Växt.

For years, Phish have celebrated another year come and gone along with their fans, often playing a string of shows leading up to New Year’s Eve. Pranks are always a part of these special occasion gigs and there's often a theme with stages being transformed to transport their phlock to other realms.

Many of Phish’ most legendary end-of-year celebratory concerts occurred in New York City at Madison Square Garden where they’ve performed to close out the year 15 times. One of the most memorable saw the band "send in the clones" on Dec. 31, 2019, to ring in another new year.

Latest News & Exclusive Videos

Behind Ryan Tedder's Hits: Stories From The Studio With OneRepublic, Beyoncé, Taylor Swift & More

Crowder Performs "Grave Robber"

NCT 127 Essential Songs: 15 Tracks You Need To Know From The K-Pop Juggernauts

5 Rising L.A. Rappers To Know: Jayson Cash, 310babii & More

Why Elliott Smith's 'Roman Candle' Is A Watershed For Lo-Fi Indie Folk

Photo: Danielle Ernst

interview

Mexican Rockers The Warning On 'Keep Me Fed' & "The Possibility That We Could Literally Do Everything"

The three sisters of the whiplashing Mexican rock band The Warning sat down with GRAMMY.com to talk about their biggest recorded leap to date, 'Keep Me Fed.'

The Warning have been around for over a decade, with three previous albums under their belt — but they've never hit with gale force quite like their single "S!CK." Get a load of them on a recent "Kimmel" performance below; when singer/guitarist Daniela "Dany" Villarreal Vélez screams the title, her bandmates — her sisters, bassist Alejandra "Ale" Villarreal and drummer Paulina "Pau" Villarreal — respond with a groovy, steamrolling riff.

From harmonies to songwriting to sheer charisma, The Warning have reached a new pinnacle with their fourth album, Keep Me Fed, which arrived June 28. It's packed with bangers: the boiling-over "Apologize," the chugging, Spanish-language "Qué Más Quieres," and pop-laced detours that stick, like "Hell You Call a Dream."

The Monterrey, Mexico trio have opened for some of rock's titans over the past few years: Guns N' Roses, Foo Fighters, and Muse. This only incentivized them to make Keep Me Fed hit as hard as humanly possible.

This involved reaching out to rock's blue-chip writers, like Dan Lancaster and Mike Elizondo, to help the songs truly hit the jackpot. But speaking to the three on a four-way call, it's clear their success really relies on their sisterly synergy: they effortlessly bounce off each other in conversation, just like they do in the studio or on a stage.

Read on for a full interview with The Warning about the road to Keep Me Fed, songwriting in Spanish and English, and how supporting the greats spurred them to make a swing that connected.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

**Bring us from the Error era to Keep Me Fed. What transpired in The Warning's history?**

Pau: We grew so much as people, through our experiences touring with Foo Fighters, Muse and Guns N' Roses. You can't help but learn and grow from all of these experiences and shows.

We were very inspired, and I feel like Keep Me Fed was the first opportunity we had to sit down and actually process everything that we had been through, and just put it directly into the music.

Ale: We were recording and writing in between tours; we had a hectic schedule. I feel like you can definitely hear that chaotic energy, and everything we lived through this past year while writing the album.

You opened for some of the biggest rock bands on the planet. Tell me more about how that fed into the music.

Pau: Seeing these amazing musicians playing every night, you can't help but want to push yourself. What made us grow was that hunger to be better. We wanted to be a good opener for these legendary bands. We wanted the crowd to be impressed; we wanted to prove ourselves to these new crowds.

And, not only with our live performances: we knew we were going to write this album, and release new music. And if these new people were going to look for our new music, we wanted it to be this insanely huge step forward in our careers.

Musically, our biggest references are Muse and Royal Blood — and we toured with them. So, by seeing what they do live, and how their ideas are [executed], we had a really good idea of how we wanted our ideas to sound live.

Dany: Coming home from the tours to process everything that you went through, I think unconsciously you let everything out, and let everything go when you're writing music. I think that played a big part in what we came back to express in the Keep Me Fed songs.

Can you talk about working with outside writers on Keep Me Fed?

Ale: We've always only worked within the few of us, so adding someone else to the mix was very different. It's so interesting to see how other people work, and working with them, and hearing all of these different ideas. I feel like we learned so much from every person we wrote with.

Dany: We have three songs with Dan Lancaster, who is touring with Muse now; he's a great producer as well. We worked alongside our producer, Anton DeLost, for the whole record. They are such a dream team, honestly. They knew how to push us toward a direction that made us get the best out of us.

We were so surprised by the stuff we lived through — very intense, specific feelings, that they can relate to in a totally different way. We managed to connect the dots between feelings and what we wanted to express.

Pau: Also, they're not necessarily rock writers. Some of them are pop. Some of them are R&B writers. It's a really big melting pot of styles and inspirations and experiences.

You start learning little tricks and tips from each person. So now, even when we're writing alone, we channel everything that we learned from these individual writing sessions.

And I feel like we look at songwriting in a new way — especially because we are Mexican, and English is not our first language. So, we write in English with a very different mindset; we think in Spanish while we are writing in English. We see language in a more phonetic way.

So, finding new ways to look at the language that we write in, and new ways to communicate what we want to say through the words or eyes of these other writers, was a very enlightening experience.

The Warning - Qué Más Quieres (Official Video)

Keep Me Fed sounds absolutely massive. How did you craft that sound?

Dany: We were very focused on making it sound as big as possible, and as close to our live performance energy as we could. Guitar-wise, we explored a lot of different fuzz pedals, which was very new to me. I wasn't very much of a fuzz girl, but oh my god, it adds so much texture, and it added to the sound that we wanted to hear.

Also, we went a lot heavier with this album. I experimented with playing with baritone guitars, so I could be a lot lower than I usually am. I love that; it makes me feel so powerful, and I think it adds a lot to the songs.

Ale: I recorded all my bass parts with a pick, which is something I don't do; I only play with my fingers. But for the recording, it sounded clearer, and made the bass stand out, as we're only a three-piece. So, I liked exploring that.

Dany: I learned to play with a slide. I had never done that before. And I had to figure out how to play it live down the road. It really pushed us, and me, to stay sharp and do what was necessary for what we wanted to express in the music.

Vocally, I experimented with a lot of different textures. We usually just go all out and do this angry screaming that I know how to do from our 10-year career. But this time, I [explored] the dynamics more and more. I went soft, I went a little more airy, and then I screamed. It was fun to get to know myself more as a singer and guitar player.

Pau: We explored a lot of different styles. You can hear different [unexpected] influences. "Burnout" is really funky and groove-driven. "Apologize" is just a very angry song. "Sharks" is this type of new thing. It's just so varied.

We let ourselves be open to the possibility that we could literally do everything. We could try everything out, and it would still fit in this album, because it was still us.

Explore The World Of Rock

HARDY On New Album 'Quit!!' & How "Trying To Push My Own Boundaries" Has Paid Off

A Beginner’s Guide To Phish: 8 Ways To Get Into The Popular Jam Band

Mexican Rockers The Warning On 'Keep Me Fed' & "The Possibility That We Could Literally Do Everything"

Watch Red Hot Chili Peppers Win Best Rock Album

Darius Rucker Shares Stories Behind 'Cracked Rear View' Hits & Why He's Still Reveling In "A Dream Come True"

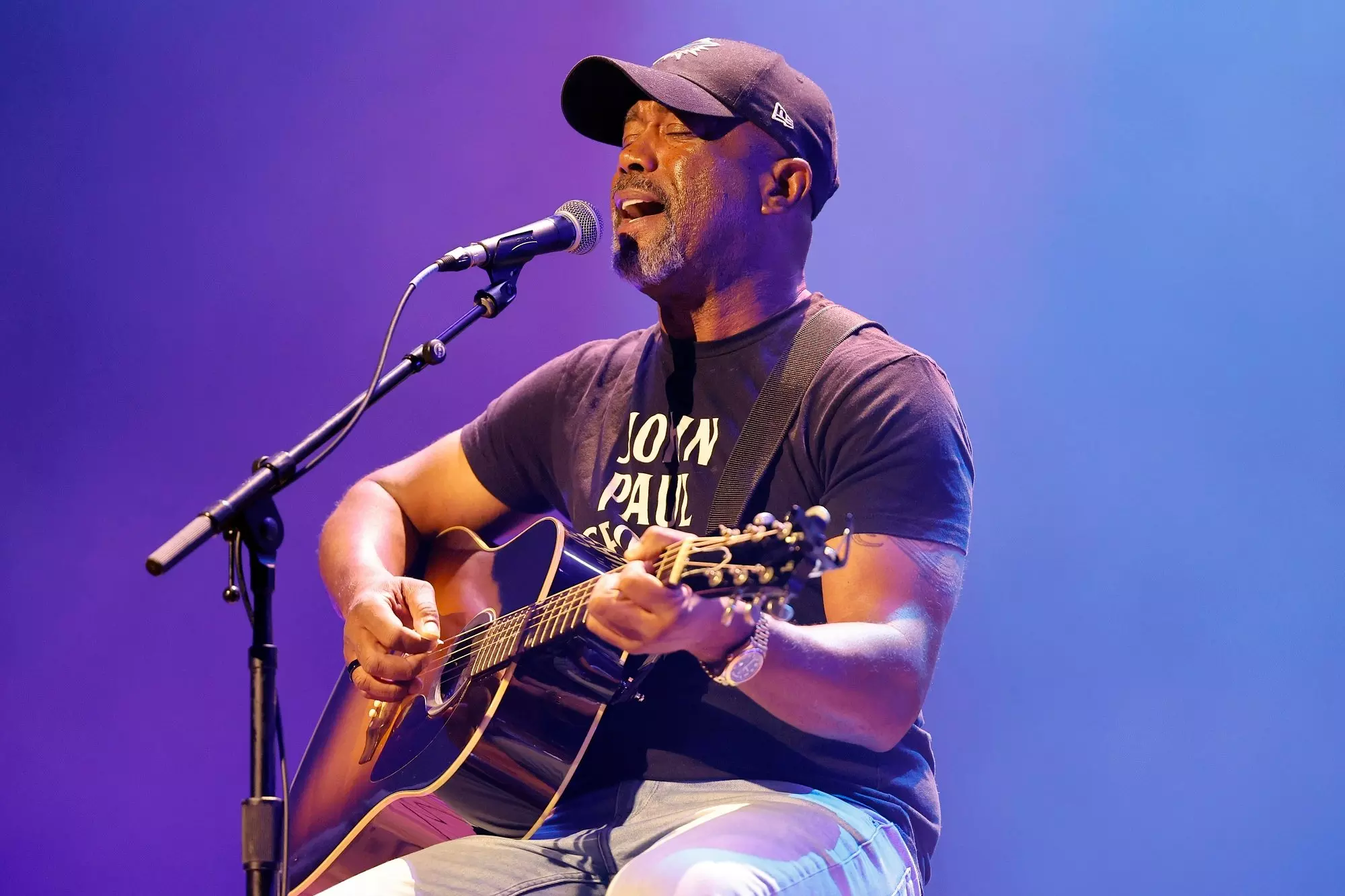

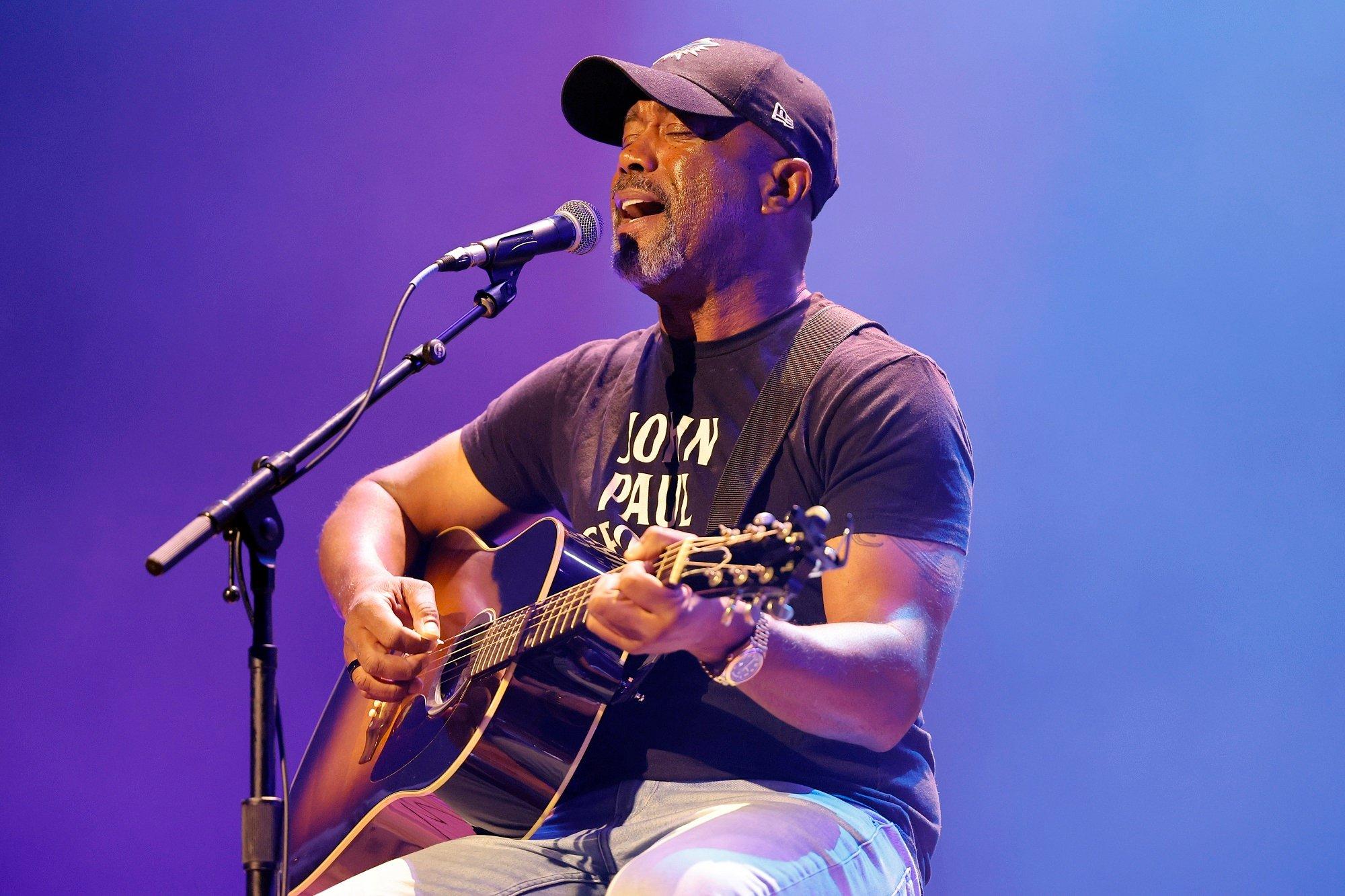

Photo: Jason Kempin/Getty Images

interview

Darius Rucker Shares Stories Behind 'Cracked Rear View' Hits & Why He's Still Reveling In "A Dream Come True"

Thirty years after Hootie & the Blowfish's seminal debut — and nearly 20 since he forayed into country music — Darius Rucker looks back on some of his fondest memories that he further explores in a new memoir, 'Life's Too Short.'

July 5, 1994 was the day Darius Rucker's life forever changed.

That was when his band, Hootie and the Blowfish, released their seminal debut, Cracked Rear View. Within a matter of months, the album went on to launch his band into the mainstream stratosphere. By mid-1995, Cracked Rear View topped the Billboard 200 — where it stayed for eight weeks — and by February 1996, the band went two-for-two at the 38th GRAMMY Awards, where they were awarded Best New Artist. Three decades on, Cracked Rear View remains one of the best-selling albums in U.S. history.

For Rucker, who has also enjoyed a successful run as a solo country act since 2008, it's all part of a triumphant journey that he recalls in his new memoir, Life's Too Short. A candid retelling of his eventful life, the book recounts the high-highs of musical dreams gloriously come true and the love of his family — including his late mother Carolyn, a frequent inspiration, particularly on his latest set, 2023's Carolyn's Boy. Rucker is also frank about his run-ins with the struggles of his massive success, including the scourge of racism he encountered along the way.

In celebration of Cracked Rear View's big anniversary and the recent release of Life's Too Short, Rucker spoke to GRAMMY.com about his band's biggest hits and career-making success, as well as the moments he knew Hootie, and his country venture, were about to be big.

How would you say Hootie's sound came about? Was it a natural evolution, or did you have a very clear sound in your head?

It was definitely natural. It all started with Mark and I in the USC dorms, realizing how much of the same music we knew and [were] jamming together — R.E.M., the Eagles, the Beatles, Simon & Garfunkel, Hank Williams, Jr. and KISS. We both grew up on a huge variety of music, and all of those influences shaped our own songs once we started performing and writing together.

There was a brief moment where we tried to do some heavier stuff as grunge was getting popular, but that wasn't us. Hootie was always going to sound like Hootie.

Congratulations on the the 30th anniversary of 'Cracked Rear View.' When you think about that time in your life and the album, I'm sure the memories just come flooding right back?

Oh, so many. You know, we'd been writing songs for so long and playing them at our live shows, doing everything independently and having pretty good success with it. But making this one was different, because we had a real record deal finally, after so many "almost" deals falling apart, and we went out to a studio in L.A. to record the album. We had Don Gehman there producing, and I just remember feeling so much joy being in that room making music together.

Does any one story stand out?

One of my favorites, and I talk about this in the book, is David Crosby coming to sing harmonies on "Hold My Hand." We were trying to figure out who would do it, and our friend Gena Rankin threw out David's name. She said it so casually, we all thought she was messing with us. There was no way a legend like him was going to come be part of this project! Sure enough, two days later he walked into the studio [to record it]. I still can't believe that happened.

Looking back, the album launched a variety of iconic singles. For example, I know "Hold My Hand" is a special one for you.

Jim "Soni" Sonefeld actually brought "Hold My Hand" to us when we were holding auditions for a drummer. He finished playing and told us he heard we were starting to write original music, so he popped a cassette in with this song on it. We obviously canceled the rest of the auditions.

What about a song like "Let Her Cry"?

I was sitting at a bar in Columbia [South Carolina] when I heard The Black Crowes sing "She Talks to Angels" for the first time. I was transfixed. I made them play it again and again until they wouldn't anymore, and then I went to every bar on the street and made them all play it.

When I finally went home, I tried to shake the song off by listening to something else great, so I put on Bonnie Raitt's Home Plate CD, and eventually decided I was going to write my own "She Talks to Angels," for Bonnie Raitt. The next morning I told Dean [Felber, the band's bassist], who I was living with at the time, that I had drunkenly recorded a song on our little four-track last night and we should listen to it because it was probably pretty funny. It wasn't funny, but it was pretty good.

"Only Wanna Be With You" was another one of the album's many hits. Where did that song come from? I'm especially wondering about one line in there: "I'm such a baby 'cause the Dolphins make me cry."

Anyone who knows my story knows that my mom, Carolyn, had a huge impact on my life and still does to this day, even though we lost her a long time ago. But she also had a specific impact on this song.

I had started writing it, with the chorus and some pretty good lyrics down, but I wanted to add more personal details and couldn't really get it right. I had taken a break from writing to watch the Dolphins game, and as they were about to lose once again after blowing a lead, my mom called. She heard me sniffling, and even though I blamed allergies, she immediately knew it was because of the game. "Unbelievable. Are those Dolphins making you cry again?!" The rest is history.

When did you realize 'Cracked Rear View' was something special?

Our fourth single "Time" really pushed us over the edge in dominating radio airwaves in a way that was hard to wrap our heads around, and really still is. I remember being in a car one time, and "Hold My Hand" was playing as soon as we turned on the radio, which was funny — but honestly, pretty expected at that point. We hit seek through the next few stations and — you can't make this up — "Only Wanna Be With You," "Let Her Cry" and, yep, "Time." Four stations, four Hootie songs. It was wild.

How did your life change?

Oh, it was a rocket ship. I always tell this story, but David Letterman heard our song on a Tuesday, put us on his show on a Friday, and by Monday, we were the biggest band in the world. It happened that quickly, and the opportunities that came from that changed our lives.

Aside from the big hits, were there any songs on the album that particularly meant something to you?

"Drowning" was an important song for me because I wrote it during the early days when we first started transitioning from covers to our own music, and I wanted to get deeply personal in what I put in songs. I put the hurt I felt from all of the racism surrounding us in that song. The lyrics literally ask, "Why is there a rebel flag hanging from the statehouse walls?"

The band supported me with that song, just like they did at shows where people casually threw the N-word at the stage. Like it has been my whole life, music was my outlet for dealing with that hurt. And I resolved that such ignorance would never stop me.

From 'Cracked Rear View' to 'Carolyn's Boy,' your songwriting as a whole has gotten much more personal. Why has that changed?

I actually think Cracked Rear View was pretty personal. The example of "Drowning" I mentioned earlier kind of shows that. But the vibe of Hootie was so happy-go-lucky that sometimes the deeper meaning of the lyrics got missed.

Country music is all about the lyrics and the storytelling, though, so I think that shows through in my newer music in a more prominent way. And with Carolyn's Boy specifically, I experienced a lot of life during the time we were writing that album. From the pandemic, to relationships, to my kids getting older and leaving the house, there was a lot of life to process and I put all of that into song.

Lightning struck twice when you branched out as a solo act and embarked into country music. When did you realize you made the correct gamble?

It was on Oct. 3, 2008. I had always wanted to make a country record, just because I love country music. When I came to Nashville, I wasn't hoping for immediate success, number one songs or platinum albums. I was just hopeful someone would give me a chance to make a record, and then maybe a chance to make another one.

But on that day in 2008, [my] debut single "Don't Think I Don't Think About It" hit the top of the charts at country radio. It was humbling, and it reaffirmed my belief in myself and my music. No matter what any of the doubters had to say about a Black man in country music, the Hootie singer in country music. The genre embraced [me], and it is still a dream come true almost 20 years later.

What was it like revisiting all of the old memories you delve into in 'Life's Too Short?'

It was therapy in a lot of ways. There are some parts, like about my dad, or my brother, that I didn't expect to talk so much about. But as you start revisiting the different chapters of your life, a lot comes to the surface that you might not have planned on, and you really start to process it, sometimes for the first time.

And then when we got into recording the audio book, reading it back added a whole other layer of emotion to the story. There were parts where I got choked up, and they kept that in the recording, which I think is really powerful — because it shows how much these stories mean to me.

Incubus On Revisiting 'Morning View' & Finding Rejuvenation By Looking To The Past