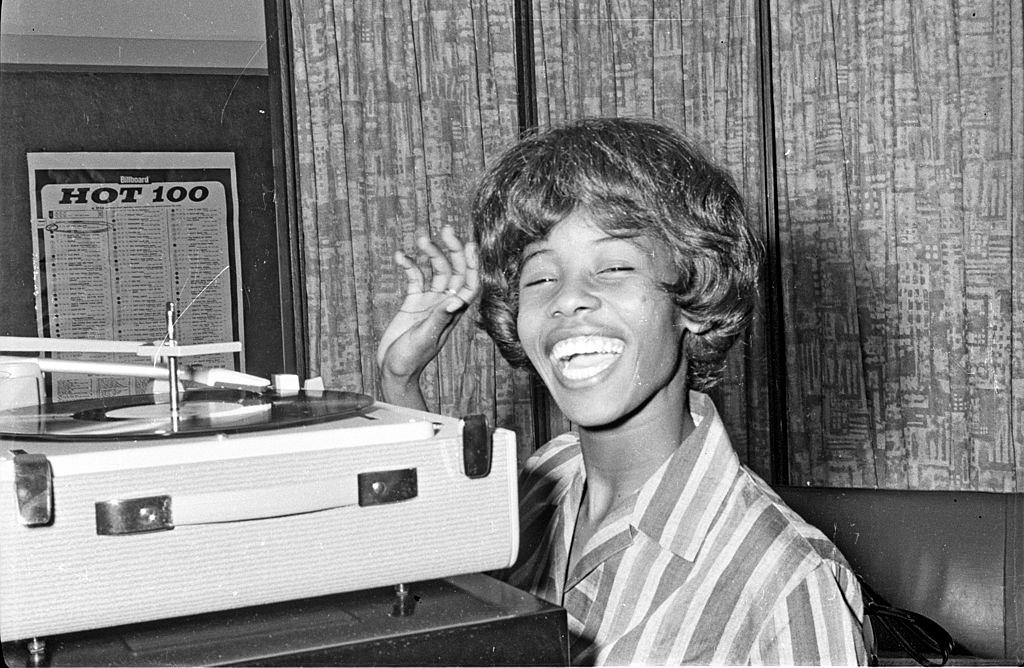

Photo: Don Paulsen/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Millie Small

news

Millie Small, Jamaican Singer-Songwriter Of Global Hit "My Boy Lollipop" And Ska Pioneer, Dies At 72

Her 1964 song, which reached No. 2 on the U.S. and U.K. charts, is considered the first true international ska hit

Millie Small, the Jamaican singer-songwriter best known for her global hit "My Boy Lollipop" and a pioneer of the ska genre, has died after suffering a stroke. She was 72.

According to a statement released by her label, Island Records, Small died "peacefully" yesterday (May 5) in London after falling ill last weekend.

In the statement, Chris Blackwell, who founded Island Records and managed the singer and also produced the hit song, said Small "opened the door for Jamaican music to the world."

"It became a hit pretty much everywhere in the world," Blackwell's statement continued. "I went with her around the world because each of the territories wanted her to turn up and do TV shows and such, and it was just incredible how she handled it. She was such a really sweet person, very funny, great sense of humor. She was really special."

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//aSM9NpsyLd0' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Born Millicent Small in Clarendon, Jamaica, in 1946, she began her singing career after winning a local talent contest and relocating to Kingston. As a teenager, she began recording and releasing music for Studio One, the island nation's iconic and much-revered recording studio and record label, and became "one of the very few female singers in the early ska era in Clarendon," according to her bio on AllMusic.

Her early singles, including "Sugar Plum" (1962), a duet with Owen Gray, and the local hit "We'll Meet," with Roy Panton as Roy & Millie, caught the attention of Blackwell, who relocated her to London, England, in 1963.

There, she recorded "My Boy Lollipop," which was originally written by Bobby Spencer of the rock 'n' roll and doo-wop group The Cadillacs and first recorded by Barbie Gaye in 1956. Small's version, released in 1964, would go on to become her breakthrough hit, ultimately peaking at No. 2 in both the U.S. and the U.K. Considered to be the first true international ska hit, selling more than 7 million copies, Small's rendition of "My Boy Lollipop" remains one of the biggest-selling reggae or ska hits of all time, according to AllMusic.

She released her debut album, My Boy Lollipop, in 1964. On the album cover, she was billed as "The Blue Beat Girl," named after a style of early Jamaican pop.

Small would again achieve moderate success in the mid-'60s: "Sweet William" (1964), a track off her debut album, became a top 40 hit in both the U.S. and U.K., while "Bloodshot Eyes" (1965) peaked at No. 48 in the U.K.

She released Sings Fats Domino, an album of Fats Domino covers, in 1965, followed by her second album, Time Will Tell, in 1970.

In 2011, as her motherland celebrated its 49th anniversary of independence, the then-Governor-General of Jamaica conferred Small with the Order Of Distinction In The Rank Of Commander "for her contribution to the Jamaican music industry," according to Jamaican daily newspaper, The Gleaner.

Photos: Courtesy of the artist; Johnny Louis/Getty Images; Courtesy of the artist; Yannick Reid; Horace Freeman; Courtesy of the artist

list

10 Artists Shaping Contemporary Reggae: Samory I, Lila Iké, Iotosh & Others

In honor of Caribbean American Heritage Month, meet 10 artists who are shaping the sound of contemporary reggae. From veterans who are hitting great strides, to promising newcomers, these acts showcase reggae's wide appeal.

The result of audacious experimentation by studio musicians and producers, reggae originated in Jamaica circa 1968 in Kingston, Jamaica. Along with its various subgenres of lovers rock, roots, dub and dancehall, reggae has influenced many music forms and found adoring audiences all over the world.

An authentic expression of the singers and musicians’ surroundings and experiences, reggae evolved from its 1960s forerunners, ska and rocksteady, shaped by contemporary influences such as American jazz and R&B, and mento, Jamaican folk music. Likewise, today’s reggae music makers draw from genres such as hip-hop (especially its trap strain) to create a generationally distinctive sound that still remains tethered to Jamaica's musical history.

In the 2020s, the Best Reggae Album GRAMMY winners reflect the diverse musical palette that comprises contemporary reggae. EDM influences and reggaeton (a genre built upon digitized dancehall reggae riddims) remixes dominate the 2024 winner Julian Marley and Antaeus' Colors of Royal. The award’s 2023 recipient — Kabaka Pyramid's The Kalling, produced by Damian and Stephen Marley — intertwines traditional roots reggae with Kabaka’s love of hip-hop. The late, great Toots Hibbert was posthumously awarded the 2021 GRAMMY for Time Tough, a hard rocking, R&B influenced gem that captured Toots’ soulful exuberance. In 2020 Koffee became the youngest and first female awardee in the category for Rapture, which features the most experimental soundscapes among this decade’s winners. Ironically, the most traditional approach to reggae is heard on American reggae band SOJA’s 2022 winner, Beauty in the Silence.

Read more: Lighters Up! 10 Essential Reggae Hip-Hop Fusions

In honor of Caribbean American Heritage Month, which was officially designated by a Presidential proclamation in June 2006, here are 10 Jamaican artists who are shaping contemporary reggae. Some are veterans who are currently hitting the greatest strides of their professional lives, others are newcomers at the threshold of extremely promising careers. All are committed to their craft and upholding reggae, even if their music ocassionally sounds unlike the reggae of a generation ago.

Kumar Bent (and the Original Fyah)

In the mid 2010s, Jamaican band Raging Fyah had a significant impact on the American reggae circuit, with their burnished, inspirational roots reggae brand as heard on such songs as "Nah Look Back" and "Judgement Day." They toured the U.S. with American reggae outfits including Stick Figure, Iration and Tribal Seeds, and supported Ali Campbell’s version of UB40 in the UK. Raging Fyah’s album Everlasting was nominated for a 2017 Best Reggae Album GRAMMY.

The following year, charismatic lead singer and principal songwriter Kumar Bent (along with guitarist Courtland "Gizmo" White, who passed away in 2023) left due to differences with their bandmates.

In 2023 Kumar teamed up with Raging Fyah alumni, drummer Anthony Watson, keyboardist Demar Gayle and backing vocalist/engineer Mahlon Moving to create The Original Fyah. In February they performed at the band’s annual Wickie Wackie festival in Jamaica and they’ve recorded an album due for upcoming release (Demar has since moved on to other projects.)

Kumar, 35, a classically trained pianist, has recorded two solo albums, including Tales of Reality with Swiss studio band 18th Parallel; they’ll tour Europe together in October. Kumar’s acoustic guitar sets have opened several dates for stalwart Jamaican band Third World this year.

Each of his musical endeavors are focused on bolstering Jamaica’s signature rhythm.

"Reggae from the 1970s and ‘80s was special because Jamaican artists made the songs exactly how they felt, and found an audience with the sounds they created," Kumar tells GRAMMY.com. "If we (Jamaicans) keep making R&B, hip-hop sounding music, we are giving away what we have for something else that we are not as good at."

Lila Iké

Lila Iké's multifarious influences run deep. "I am a Jamaican artist who is influenced by different music and you’re going to hear that coming through," she said in a June 2020 interview with The Daily Beast, following the release of her debut EP The ExPerience.

While Jamaican music expanded beyond what Iké called "the purist reggae vibe," she told The Daily Beast that "it’s important to maintain the music’s indigenousness. I incorporate that into the rhythms I use and my singing style because I want young people to know, this music doesn’t start where you hear it, it has transcended many years and changes."

Born Alecia Grey, she chose the name Lila, which means blooming flower, and Iké, a Yoruba word meaning the Power of God. Her vocals are a singular, mesmerizing blend of smoky, soulful expressions with a laid back yet poignant rendering. Lila’s effortless versatility is rooted in her upbringing in the rural community of Christiana. Her mother listened to a wide range of music, R&B, jazz, soul, country and reggae, with Lila, her mom and sisters singing along to all of it.

Lila moved to Kingston to pursue her musical ambitions; she performed on open mic nights and posted her songs on social media. Protoje reached out to her via Twitter with an invitation to record. From that initial meeting, Protoje has managed and mentored her career. Through his label In.Digg,Nation Collective’s deal with RCA Records, Lila will release her debut album later this year; Protoje also produced the album’s first single, the reggae/R&B slow jam duet "He Loves Us Both" featuring H.E.R.

Hezron

A passionate singer whose vocals marry the grit of Otis Redding with the cool of Marvin Gaye, singer/songwriter and musician Hezron has yet to achieve the widespread impact his talents merit, although he's been planting seeds since 2010. That year, his single "So In Love" was the first of Hezron's substantial musical fruits and exceptional catalog.

On his 2022 self-produced, remarkable album Man on a Mission, Hezron explores a range of Jamaican music and history. On the rousing ska track "Plant A Seed," Hezron's guttural, gospel inflected delivery is reminiscent of Toots Hibbert as he warns his critics, "You think you bury me and done but you only planted a seed." The album also features a scorching R&B jam "Tik Tok I’m Coming"; an acoustic, mystical acknowledgement of Rastafari, "Walk In Love and Light"; and a stirring plea to "Save The Children." The album’s title track is a spirited reggae anthem offering support to anyone in pursuit of their goals while underscoring Hezron’s own purpose.

"Man on a Mission is about my personal journey, the obstacles I’ve had to overcome in the music business and beyond. I’m telling myself, telling the world, this man is on a mission to restore Jamaican music to a prominent place internationally," Hezron tells GRAMMY.com.

In November 2023 Hezron embarked on a global mission: a two-month tour of Ghana, followed, this year, by summer shows in Canada and the U.S. before returning to Africa, with dates in Ivory Coast, Kenya, and South Africa.

Iotosh

A self-taught multi-instrumentalist, songwriter and vocalist, Iotosh (born Iotosh Poyser) made his name as a producer who can seamlessly blend disparate influences into progressive reggae soundscapes. He’s produced singles for several marquee acts who emerged from Jamaica’s reggae revival movement of the previous decade including Koffee’s "West Indies," the title track on Jah9’s Note to Self featuring Chronixx, and Jesse Royal’s "Rich Forever", featuring Vybz Kartel. He also produced five of the 10 tracks on Protoje’s GRAMMY-nominated album Third Time’s The Charm.

Iotosh’s parents (Canadian music TV journalist Michele Geister and Jamaican singer/songwriter/producer Ragnam Poyser) came from different musical worlds, so he heard a multiplicity of genres growing up, including hip-hop, rock, funk, soul, reggae and R&B. Iotosh wanted to replicate all of those sounds when he started making music, which led to his genre blurring approach.

As an artist, his 2023 breakout single the meditative "Fill My Cup" (featuring Protoje on the remix) was followed this year by "Bad News," which explores grief that follows losing a loved one, both on one-drop reggae rhythms. He describes his debut eight-track EP, due in September, as "a mix of traditional reggae and elements of contemporary music, pop, hip-hop and R&B."

"In my productions, I try to have some identifiable Jamaican aspects, usually the bassline, which I play live," Iotosh tells GRAMMY.com. "Reggae is based on a universal message, it’s peace and love but contextually it comes from a place of enlightening people about forces of oppression. If that message is in the music, it’s still reggae, no matter what it sounds like."

Iotosh will make his New York City debut on July 7 at Federation Sound’s 25th Anniversary show, Coney Island Amphitheater.

Mortimer

Producer Winta James first heard Mortimer while working on sing-jay Protoje’s acclaimed 2015 album Ancient Future, and decided he was the right singer to provide the evocative hook on the opening track, "Protection." About a year after they recorded the song, Mortimer became the first artist Winta signed to his company Overstand Entertainment.

In 2019 Mortimer (born Mortimer McPherson) released his impressive EP, Fight the Fight; single "Lightning," was especially noteworthy for its roots-meets-lovers rock sound anchored in a heavy bass and delicately embellished with a steel guitar. Mortimer’s sublime high register vocals express a refreshingly vulnerable perspective: "Girl, my love grows stronger each day, baby please don't hurt me just because you know I'll forgive."

"The songs that get me the most are coming from a place deep within," Mortimer told me in a January 2020 interview. "I started out writing what I thought was expected of me as a Rasta, militant, social commentaries, but it was missing something. Before I am a Rastaman, I am a human being, so I dig deep, expressing my feelings simply, truthfully."

Mortimer’s debut album is due in September and his latest single, "Not A Day Goes By," addresses his struggles with depression: "I’ve given up 1000 times, I’ve even tried to take my own life," he sings in a haunting tone. Mental health struggles remain a taboo topic in reggae and popular music overall; Mortimer’s raw, confessional lyrics demonstrate his courageousness as an artist, and that bravery will hopefully inspire others going through similar struggles to speak out and get the help they need.

Hector "Roots" Lewis

Earlier this year, Hector "Roots" Lewis made his acting debut in the biopic Bob Marley: One Love, earning enthusiastic reviews for his portrayal of the late Carlton "Carly" Barrett, the longstanding, influential drummer with Bob Marley and The Wailers. Formerly the percussionist and backing vocalist with Chronixx’s band Zinc Fence Redemption, Hector is blazing his own trail as a vocalist, songwriter and musician.

The son of the late Jamaican lover’s rock and gospel singer Barbara Jones, Hector’s profound love for music began as a child. In 2021, Chronixx launched his Soul Circle Music label with Hector’s single "Ups and Downs," an energetic funky romp that’s a testament to music’s healing powers. The song’s lyric "never disrespect cuz mama set a foundation" directly references Hector’s mother as the primary motivating force for his musical pursuits.

In 2022 Hector toured the U.S. as the lead singer with California reggae band Tribal Seeds (when lead singer Steven Jacobo took a hiatus) taking his dynamic instrumental and vocal abilities to a wider audience. The same year, Hector released his five-track debut EP, D’Rootsman, which includes regal, soulful reggae ("King Said"), 1990s dancehall flavor ("Nuh Betta Than Yard") and R&B accented jams "Good Connection."

Co-produced with Johnny Cosmic, Hector’s latest single "Possibility" boasts an irresistible bass heavy reggae groove. On his Instagram page, Hector dedicates "Possibility" to people who are facing the terrors of "warfare, colonialism, depression and oppression," urging them to "believe in the "Possibility" that they can be free from that suffering."

Read more: 7 Things We Learned Watching 'Bob Marley: One Love'

Hempress Sativa

The daughter of Albert "Ilawi Malawi" Johnson, musician and legendary selector with Jah Love sound system, Hempress Sativa was raised in a Rastafarian household where music played an essential role in their lives. Performing since her early teens, she developed an impressive lyrical prowess and an exceptional vocal flow, effortlessly switching between singing and deejaying.

Consistently bringing a positive Rasta woman vibration to each track she touches, Hempress Sativa’s most recent album Chakra is a sophisticated mix of reggae rhythms, Afrobeats ("Take Me Home," featuring Kelissa), neo-soul ("The Best") and cavernous echo and reverb dub effects ("Sound the Trumpet"), a call to action for spiritual warriors. On "Top Rank Queens" Hempress Sativa trades verses with veterans Sister Nancy and Sister Carol, each celebrating their deeply held values and formidable mic skills as Rastafari female deejays.

Hempress Sativa is featured in the documentary Bam Bam The Sister Nancy Story, (which premiered at the Tribeca Festival on June 7) recounting the legendary toaster’s influence on her own artistry. Speaking specifically about Sister Carol, Hempress tells GRAMMY.com, "She is my mentor and to see her, as a Rastafari woman from back in the 1970s, maintain her standards and principles, gives me the confidence moving forward that I, too, can find a space within this industry where I can wholeheartedly be myself."

Learn more: The Women Essential To Reggae And Dancehall

Tarrus Riley

One of the most popular reggae songs of the 2000s was Tarrus Riley’s dulcet lover’s rock tribute to women "She’s Royal." Released in 2006 and included on his acclaimed album Parables, "She’s Royal" catapulted Tarrus to reggae stardom; the song’s video has surpassed 114 million YouTube views.

Tarrus has maintained a steady output of hit singles, while his live performances with the Blak Soil Band, led by saxophonist Dean Fraser, have established a gold standard for live reggae in this generation. Tarrus’s expressive, dynamic tenor is adaptable to numerous styles, from the stunning soft rocker "Jah Will", to the thunderous percussion driven celebration of African identity, "Shaka Zulu Pickney" and the EDM power ballad "Powerful," a U.S. certified gold single produced by Major Lazer, featuring Ellie Goulding.

His 2014 album Love Situation offered a gorgeous tribute to Jamaica’s rocksteady era (during which time his father, the late Jimmy Riley, started out as a singer in the harmony group the Sensations). Tarrus’s most recent album 2020’s Healing, includes meditative reggae ("Family Tree"), trap dancehall with Teejay referencing racial and political sparring on "Babylon Warfare," and the pop dancehall flavored hit "Lighter" featuring Shenseea (the song’s video has surpassed 102 million views).

Healing’s title track ponders what the new normal will be like, "without a simple hug, so tight and warm and snug/what will this new life be like, without a simple kiss, Jah knows I'd hate to miss."

Recorded and released at the height of the pandemic, Healing is deserving much greater recognition for its luminous production (by Tarrus, Dean Fraser and Shane Brown) brilliant musicianship, nuanced songwriting and forthright expression of the myriad, conflicting emotions many underwent during the lockdowns.

Samory I

Samory I is among the most compelling Jamaican voices of this generation, whose mesmeric tone is both a guttural cry and a clarion call to collective mobilization. Born Samory Tour Frazer (after Samory Touré, who resisted French colonial rule in 19th century west Africa), Samory I released his critically acclaimed debut album, Black Gold, in 2017.

His latest release Strength is produced by Winta James, and was the only reggae title included on Rolling Stone’s Best 100 albums of 2023. The modern roots reggae masterpiece features the affirming "Crown," on which Samory commands, "I stand my ground, I will not crumble/I keep my crown here in this jungle." Mortimer is featured on "History of Violence," which details the generational trauma that plagues ghetto residents over a classic soul-reggae riddim. "Blood in the Streets" is a blistering roots reggae anthem, an anguished exploration of the conditions that have led to the violence: "Shame to say the system that should be protecting Is still the reason we suffer/The perpetrators blame the victims, do they even listen? Can they hear us from the gutter?"

Despite the societal and personal suffering that’s conveyed ("My Son" bemoans the death of Samory’s firstborn), Samory I offers "Jah Love" urging the wronged and the wrongdoers to ‘Show no hate, hold no grudge, seek Jah love," It’s an inspirational conclusion to Strength, rooted in Rastafari’s deeply meshed mysticism and militancy.

Romain Virgo

There’s a scene in the video for Romain Virgo’s 2024 hit "Been there Before" where he sits alone in an empty room cradling a gold object with three shooting stars; those familiar Romain’s career beginnings will recognize it as the trophy the then 17-year-old won in the Jamaica’s talent contest Digicel Rising Stars, in 2007. "Been There Before" is a compelling sketch of Romain’s life’s struggles, yearning for something better, as set to a throbbing bassline: "To be someone was my heart’s desire/so me never stop send up prayer," he sings in a melancholy, quavering tone.

Growing up poor in St. Ann, Jamaica, the trophy represents the contest victory that changed Romain’s life. One of the Rising Star prizes was a recording contract with Greensleeves/VP Records. On March 1, Romain released his fourth album for VP The Gentleman, one of 2024’s finest reggae releases, evidencing Romain’s increasing sophistication as a writer and nuanced vocalist.

Throughout his career Romain has vacillated between romantic lover’s rock stylings ("Stars Across The Sky"), reggae covers of pop hits (Sam Smith’s "Stay With Me") that are so good, you’ll likely forget the originals, and organic, tightly knitted collabs including the aforementioned "Been There Before" featuring Masicka, all of which has created Romain’s large, loyal fan base and a hectic international performance schedule.

Yet, Romain’s greatest success might be maintaining the wholesome, humble personality that captivated Jamaican audiences when he won Rising Stars 17 years ago. "People have seen me grow in front of their eyes," Romain tells GRAMMY.com. "I enjoy singing positive music, knowing my songs won’t negatively impact kids. Being a husband and father now comes with much more responsibility in holding on to those values, it feels like a transition from a gentle boy into a gentleman."

Remembering Coxsone Dodd: 10 Essential Productions From The Architect Of Jamaican Music

PRIDE & Black Music Month: Celebrating LGBTQIA+ & Black Voices

Listen To GRAMMY.com's 2024 Pride Month Playlist Of Rising LGBTQIA+ Artists

9 New Pride Anthems For 2024: Sabrina Carpenter's "Espresso," Chappell Roan's "Casual" & More

What's The Future For Black Artists In Country Music? Breland, Reyna Roberts & More Sound Off

Why Beyoncé Is One Of The Most Influential Women In Music History | Run The World

9 Ways To Support Black Musicians & Creators Year-Round

How Beyoncé Is Honoring Black Music History With 'Cowboy Carter,' "Texas Hold Em," 'Renaissance' & More

The Evolution Of The Queer Anthem: From Judy Garland To Lady Gaga & Lil Nas X

15 LGBTQIA+ Artists Performing At 2024 Summer Festivals

50 Artists Who Changed Rap: Jay-Z, The Notorious B.I.G., Dr. Dre, Nicki Minaj, Kendrick Lamar, Eminem & More

Fight The Power: 11 Powerful Protest Songs Advocating For Racial Justice

How Rihanna Uses Her Superstardom To Champion Diversity | Black Sounds Beautiful

How Beyoncé Has Empowered The Black Community Across Her Music And Art | Black Sounds Beautiful

5 Women Essential To Rap: Cardi B, Lil' Kim, MC Lyte, Sylvia Robinson & Tierra Whack

Celebrate 40 Years Of Def Jam With 15 Albums That Show Its Influence & Legacy

Watch Frank Ocean Win Best Urban Contemporary Album At The 2013 GRAMMYs | GRAMMY Rewind

A Brief History Of Black Country Music: 11 Important Tracks From DeFord Bailey, Kane Brown & More

10 Women In African Hip-Hop You Should Know: SGaWD, Nadai Nakai, Sho Madjozi & More

10 Artists Shaping Contemporary Reggae: Samory I, Lila Iké, Iotosh & Others

The Rise Of The Queer Pop Star In The 2010s

How Sam Smith's 'In The Lonely Hour' Became An LGBTQIA+ Trailblazer

How Queer Country Artists Are Creating Space For Inclusive Stories In The Genre

How Jay-Z Became The Blueprint For Hip-Hop Success | Black Sounds Beautiful

How Kendrick Lamar Became A Rap Icon | Black Sounds Beautiful

Dyana Williams On Why Black Music Month Is Not Just A Celebration, But A Call For Respect

6 LGBTQIA+ Latinx Artists You Need To Know: María Becerra, Blue Rojo & More

7 LGBTQ+ Connections In The Beatles' Story

Breaking Down Normani's Journey To 'Dopamine': How Her Debut Album Showcases Resilience & Star Power

10 Alté Artists To Know: Odunsi (The Engine), TeeZee, Lady Donli & More

Celebrating Black Fashion At The GRAMMYs Throughout The Decades | Black Music Month

FLETCHER Is "F—ing Unhinged" & Proud Of It On 'In Search Of The Antidote'

For Laura Jane Grace, Record Cycles Can Be A 'Hole In My Head' — And She's OK With That

15 Essential Afrorock Songs: From The Funkees To Mdou Moctar

50 Years In, "The Wiz" Remains An Inspiration: How A New Recording Repaves The Yellow Brick Road

Why Macklemore & Ryan Lewis' "Same Love" Was One Of The 2010s' Most Important LGBTQ+ Anthems — And How It's Still Impactful 10 Years On

Songbook: The Complete Guide To The Albums, Visuals & Performances That Made Beyoncé A Cultural Force

Why Cardi B Is A Beacon Of Black Excellence | Black Sounds Beautiful

Queer Christian Artists Keep The Faith: How LGBTQ+ Musicians Are Redefining Praise Music

9 Revolutionary Rap Albums To Know: From Kendrick Lamar, Black Star, EarthGang & More

9 "RuPaul's Drag Race" Queens With Musical Second Acts: From Shea Couleé To Trixie Mattel & Willam

5 Black Artists Rewriting Country Music: Mickey Guyton, Kane Brown, Jimmie Allen, Brittney Spencer & Willie Jones

How 1994 Changed The Game For Hip-Hop

How Whitney Houston’s Groundbreaking Legacy Has Endured | Black Sounds Beautiful

LGBTQIA+-Owned Venues To Support Now

Celebrate The Genius Of Prince | Black Sounds Beautiful

Explore The Colorful, Inclusive World Of Sylvester's 'Step II' | For The Record

Black-Owned Music Venues To Support Now

5 Artists Fighting For Social Justice Today: Megan Thee Stallion, Noname, H.E.R., Jay-Z & Alicia Keys

Artists Who Define Afrofuturism In Music: Sun Ra, Flying Lotus, Janelle Monae, Shabaka Hutchings & More

5 Trans & Nonbinary Artists Reshaping Electronic Music: RUI HO, Kìzis, Octo Octa, Tygapaw & Ariel Zetina

From 'Shaft' To 'Waiting To Exhale': 5 Essential Black Film Soundtracks & Their Impact

5 Emerging Artists Pushing Electronic Music Forward: Moore Kismet, TSHA, Doechii & Others

5 Artists Essential to Contemporary Soca: Machel Montano, Patrice Roberts, Voice, Skinny Fabulous, Kes The Band

How Quincy Jones' Record-Setting, Multi-Faceted Career Shaped Black Music On A Global Scale | Black Sounds Beautiful

5 Black Composers Who Transformed Classical Music

Brooke Eden On Advancing LGBTQ+ Visibility In Country Music & Why She's "Got No Choice" But To Be Herself

Let Me Play The Answers: 8 Jazz Artists Honoring Black Geniuses

Women And Gender-Expansive Jazz Musicians Face Constant Indignities. This Mentorship Organization Is Tackling The Problem From All Angles.

Histories: From The Yard To The GRAMMYs, How HBCUs Have Impacted Music

How HBCU Marching Band Aristocrat Of Bands Made History At The 2023 GRAMMYs

Photo: Gus Stewart/Redferns

interview

Madness Frontman Suggs Talks New Album, First U.S. Tour & Getting Kicked Off "Top Of The Pops" — Four Times

Ahead of their appearance at Las Vegas' Punk Rock Bowling fest and first American shows in 10 years, Madness' lead singer Suggs details the band's hit-filled history, 2023 album and coming up Two Tone.

American audiences may only know "Our House," but there’s much more to Madness than their lone Stateside mega-hit.

Prior to their 1982 smash, the English band enjoyed immense commercial success in their home country. Between 1979 and 1981, Madness sent nine consecutive singles into the Top 10 of the UK Official Singles Chart.

"It was a few years of hard work and all of a sudden, we were the most successful band in England," says Madness frontman Suggs (born Graham McPherson), chatting from London. "That happened because people f—ikn’ dug the tunes we made."

Madness also helped bring ska to the masses. Alongside comrades like the Specials, the London septet were leaders of the late ‘70s British ska boom, which combined Jamaican rhythms with punk swagger, and united Black and white working-class kids. Among their hits from this era were "One Step Beyond" (1979), "Baggy Trousers" (1980) and "House of Fun" (1982).

With their street-savvy fashions and Monty Python-style music videos (which caught the eye of Honda and led to a series of advertisements in the early '80s), Madness have been fixtures in UK culture and beyond for over 40 years. They endured so strongly that their 13th LP, 2023’s Theatre of the Absurd Presents C’est la Vie, hit No. 1 on the UK Official Albums Chart — their first studio album to reach the summit.

Beginning May 22, Madness will tour the U.S. for the first time in 10 years, including a headline slot at Las Vegas’ Punk Rock Bowling festival, alongside Devo and Descendents.

On the phone, Suggs is chatty and jovial, quick to break into song or pull a good story from his band’s topsy-turvy history. Madness once turned down a chance to play Madison Square Garden as "Our House" surged in 1983. (They’d already performed on "SNL" and "Our House" was an MTV staple.) Madness could have been a much bigger band in America. But after years of non-stop touring and promotion in the UK, Madness was nearing its breaking point. "We had f—in’ 20 hits and we were all getting a bit tired," Suggs remembers. "I see the Pretenders, 18 months touring America! So, we never really continued." In 1986, Madness went their separate ways.

A decade later, ska was enjoying a moment in the sun in America as groups like the Mighty Mighty Bosstones, No Doubt and Reel Big Fish dominated airwaves during the genre's "third wave." Over in the UK, a rejuvenated Madness was enjoying its elder statesman status, drawing massive festival crowds since reuniting in 1992. No Doubt frequently cited Madness as an inspiration and even tapped keyboardist Mike Barson to play on one of their songs. And the fire still burns. At Coachella 2024, No Doubt covered Madness’ rendition of "One Step Beyond," itself a cover of a ‘60s classic by Jamaican ska legend Prince Buster.

Madness — whose current lineup also includes guitarist Chrissy Boy, saxophonist Lee Thompson, bassist Mark Bedford, and drummer Woody — has earned its place in rock history. Their classics still bring crowds to a frenzy and, as their latest album proves, fans are still enthralled by what Suggs and company have to say.

GRAMMY.com recently caught up with the Madness singer for a career-spanning swath of topics: crafting tunes in the modern day, some sage advice he got from Clash frontman Joe Strummer, why Madness kept getting banned from "Top of the Pops," and much more.

Was there a moment you realized "Our House" was going to be a much bigger song than your previous hits?

When it was a hit in America, that was definitely an indication. And that’s the alchemy of music — you just don’t know when you’re doing it at the time. I remember we were rehearsing, when the song started… our bass player Mark [Bedford] goes [hums "Our House" intro], dum-dum, dum-dum-de-dum-dum… There wasn’t a chorus at the time, so our producer Clive [Langer], just sang, "Our house, in the middle of the street," just joking.

But without that, it wouldn’t have been the hit that it is. [Songs] are like babies. You have them, you bring them up, and then they go out into the world, and you don’t know where they’re gonna go. It’s not up to you. It’s up to other people to decide if they like them or not.

We’d been in America for a month and suddenly "Our House" was a massive hit. We’d been offered to play Madison Square Garden but we were just tired and wanted to go home. We all had kids. We didn’t do a few gigs [that] we were offered in America that might have changed the situation.

We [weren't] arrogant — but we were a bit. And we were so popular in England. We were making a very good living; we didn’t really have to go anywhere anymore. We just decided that it was kind of too late to try and break — whatever that word means — America. It was a great hit, it was fantastic, but that was kind of it.

What do you remember from the first time Madness toured the States?

It was 1979 or so… It was a really big, eye-opening experience. There were seven [of us] in the band, so probably 10 of our friends [including crew]. We were like a party on the road, we didn’t really need anyone else’s company. Coming over the Brooklyn Bridge and seeing New York, you know what I mean? When you come from London — I mean, London isn’t small — but you don’t compare it to New York.

And then L.A. and all the palm trees. I remember we played at Whisky a Go Go. We did two shows a night: one at 11 and one at 2 in the morning — my suit was still wet.

It was kind of off because [L.A.] was still catching up with punk. You had the Dead Kennedys, Black Flag, X. People were doing all this mad punk dancing and the worm or whatever, writhing about on the floor. We’d sort of done that in London; we’d had the Sex Pistols and the Clash. We were into something else, which was dancing, and playing music by Black origin. We weren’t just thrashing about and spitting at each other. But that kind of thing was still going on, which made it a bit difficult for us because a lot of the places we were playing were really punk. And we weren’t punk. We were over that.

By the time "Our House" came around in '82, I’d think America was starting to catch up.

By then you had Blondie, the CBGB scene, Talking Heads, and it started to make more sense to us. With post-punk, there were grooves suddenly. It was offbeat, but it wasn’t anger.

When Madness first started playing, what were the crowds like?

It was just our friends. We started off in a pub in Camden Town, where we were living. We got a residency, every Wednesday night. First week, there’d be 10 people. Second week, 30, 40, 60, 80, 90, 100, and then two months later, we had a queue around the block. The music we were playing, which was ska, and the clothes we were wearing was kinda different than everybody else around.

Then we got a gig supporting the Specials in a pub in West London. They sort of appeared out of nowhere — Coventry — which is quite a long way from London. And they were wearing the same clothes as us, playing the same kind of music. I remember [Specials singer] Neville [Staple] was shooting holes in the ceiling with a starting pistol and I just thought, Crikey, these are kooks. We might be onto something. I remember Johnny Rotten getting out of a cab and going, "Are you for real?" And these kids went, "Yeah, you f—ing arse." It was the transition of power. It wasn't that long: ‘77, punk. ‘78, us. And suddenly you got the Specials, the Beat, the Selecter. Two-tone became this massive phenomenon in London. So we went on tour with them: the Specials, Selecter, Beat.

I remember being with Joe Strummer from the Clash and I was walking through a playground with him. I can’t remember where we were going, but all the kids were singing "Baggy Trousers" on the swings. And I’m going, "I want to be cool, I don’t want school kids." And he went, "No, you’ve got it wrong, mate. You want to have young kids, that’s the best thing that can happen. As far as I’m concerned, it’s the young people you want to connect with."

When you’ve got pretty naive school kids singing your songs, you’ve definitely done something you should be proud of.

What was Camden Town like when you were growing up there?

It was rough, man. You know, people now in London are getting more and more scared, lot of knives flyin’ and gangs, but it was the same. You lived in a certain area and you would be very wary of another area across the road because you could be stabbed, shot. The greatest thing was the music.

Every pub had a stage and there’d be music on every night. In that period, punk was still there, then you got goth, you got psychobilly, rockabilly, then you got new romantic. Every pub you went to was something going on. Different scenes, all these kids.

The pride I have [as one of] these working class kids. There’s no money, you just tried: this is what you’re gonna wear, and this is what you’re into. And suddenly a whole scene started. It was totally organic and individual. It wasn’t trend sections, fashion magazines; it was just kids doing what they want.

Where you grew up, what were race relations like?

They were difficult. And we got caught up in that, unfortunately, because we were all white… Although our original drummer was Black, but he left because we were too s—. Like I said, there was all these different scenes and the scene we were into was ska and reggae. And you had this whole culture — from the mods to the skinheads to the suedeheads in the late ‘60s and ‘70s — which was all about fashion and listening to that music, but it got usurped by these [racist] skinheads who started to take it the other way.

We’d be playing concerts and there’d be all sorts of racism going on and we’d have to deal with it in our own way. I remember jumping into the audience a few times and getting beaten up. It went away, fortunately. Only a couple years: probably ‘78, ‘79 maybe. Even the Specials were getting it, and they had Black people in their own group. They’d get people f—ing sieg heiling. It’s a fucking long story.

What we had here was football hooliganism, which has now become very popular in Italy, France, and Germany. It’s one of our greatest exports. [Laughs.] It was easier for them to come to rock concerts than football matches, where there were loads of police.

How did the commercial success first come?

By being really good. People saw what we’d done. It was a few years of hard work and all of a sudden, we were the most successful band in England. That happened because people f—in’ dug the tunes we made. Then we split up in 1985 and I think we were still the most successful band of the ‘80s… in England. Ha ha!

"The Prince" on 2 Tone [Records] got to No. 16, then we had [our debut album] One Step Beyond get to No. 2, then we had "House of Fun" [reach No. 1]. We just had hit after hit, you tell me.

Music videos played a big role in Madness' success, right?

That had just started. This was before MTV. We went to Stiff Records [in 1979]. We’d been on 2 Tone [Records], but we decided we wanted to spread our wings and Stiff had Elvis Costello, Ian Dury, Kirsty MacColl, the Damned. Dave Robinson, who ran that label, also saw the potential that we were all quite theatrical, so we started making videos.

[Television program] "Top of the Pops" had 20 million viewers; it only was allowed one promo pop video, and we were always the one that they showed. When we did "Baggy Trousers," there was a feeling in the air. People would talk about our videos, and it definitely added to the potency of what we were doing.

The intellectual types and the tastemakers, the people who make and break you, just thought we were a flash in the pan joke, and the music got slightly sidelined. Only recently we’ve had much better reviews of our history. We put a lot of effort into the music [and] those videos.

There’s so much going on in those songs, musically, if you really listen.

We’d have friends, musicians, play covers and they’d go, "We can’t play your songs, it’s too complicated." We had seven of us, all wrote songs, so we were in constant competition with each other. You couldn’t just go, "Mine’s the best." You had to actually write the best song.

So many bands with two or three songwriters are fighting all the time, or just break up. How did Madness do it with so many?

Tolerance is the main thing. The underlying reason is we were friends from when we were at school. We were famous around our way. It was a gang called the Aldenham Glamour Boys, and to be in or amongst them, you were famous. So by the time we got the band going, we weren’t really bothered by other people’s impressions of us.

On "Top of the Pops," we got banned four times. The girl who used to do our promotions said, "Do you realize people would give their right arm to be on this?" And I said, "The thing is, we’re just not right arm-giving people."

What were the four things you got banned from "Top of the Pops" for?

The first time was when one of our friend’s brothers was in prison and he held up a sign saying, "This is for prisoner number 44224022." That wasn’t allowed. The second time, we got on a lift with this dance troupe and the lift plummeted into the basement because there were too many of us. The third time, Lee [Thompson], our saxophone player, had a t-shirt that said, "I need the BBC" and then he had another t-shirt underneath that said, "Like a hole in the head." And I can’t remember what the fourth one was.

When America had its brief ska moment in the ‘90s, did Madness get any new attention?

I don’t think so, no, because we had accepted that it was too late. It was great to see, all the Americans, Mighty Mighty Bosstones or whoever checking us. But we weren’t going to go back. If it had been 20 years earlier, it would have helped. But it was too late, like, "Who are these old farts?" [Laughs.]

When Madness got back together in the ‘90s, what was that like?

Vince Power, who just passed away, a great promoter, used to do this Irish festival, Fleadh, in North London. We all used to go. And he says, "When’s the last time you played?" And I said, "Well, probably about six years ago." And he said, "Why don’t you do a one-off comeback?"

So we did Madstock! in 1992. We didn’t know if anyone was going to turn up. 35,000 people turned up. So we put on another one. And 70,000 people turned up. There was an earthquake, 4.5 on the Richter scale, people were jumping up and down. And they had to evacuate people out of their houses, flats, and apartments because of the earthquake that we’d created. We put out a greatest hits album, it goes to No. 1, sold 2 million copies, blah, blah, blah… And we’ve been going longer now on this bit than we did on that first bit.

It’s really interesting to hear how you’ve been part of rock music through so many eras.

I’ve just done a couple songs with Paul Weller, he’s a friend of mine from the old days. We were working on a tune and I went, "Look Paul, it’s only music." And he said, "No, it f—ing isn’t." [Laughs.] And it’s true innit? We made a lot of f—ing good pop music. It’s something I’m very proud of. It’s the soundtrack of our lives. When you hear a tune, you remember exactly where you were.

When you wrote the lyrics for the new album, Theatre of the Absurd, what was on your mind?

We all write. We had 40 songs. During the lockdown, for that two years, the worst way to communicate is email. People were losing their minds. So I thought we were going to fall out and never speak to each other… And we made a record I think is good. I mean, [it went] No. 1 in England; that’s the first number one [studio] album we ever had.

I wrote the first song on the album, "Theatre of the Absurd." I was just sitting on my own, stuck, and I was imagining being in some old theater with all the doors locked, not being able to get out. Theatre of the Absurd was a French artistic [concept] where things became so absurd, it was all gobbledygook. They just made up words.

I’m really fortunate. This band of mine, they're a dysfunctional family, it’s very difficult to be in. But it’s like the philosophers the Eagles once said, "You can check out any time you like, but you can never f—in’ leave."

But I’m looking forward to playing America. The fella from "Curb Your Enthusiasm," Larry David wants to introduce us.

Are you gonna do that?

You know, Helen Mirren did a bit on our new album, [so did] Martin Freeman, actors from England. Getting someone from America who likes us, I can’t see the problem with that. We shall see.

Watch: "A History Of L.A. Ska" Panel At The GRAMMY Museum With Reel Big Fish, NOFX & More

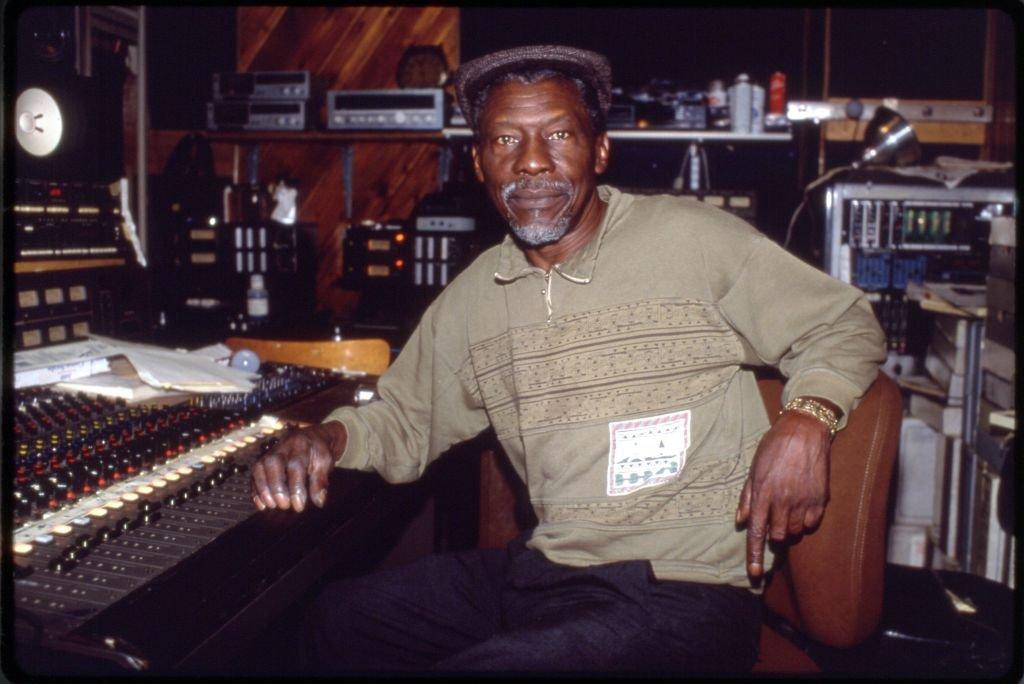

Photo: David Corio/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

list

Remembering Coxsone Dodd: 10 Essential Productions From The Architect Of Jamaican Music

Regarded as Jamaica’s Motown, Coxsone Dodd's Studio One helped launch the careers of legends such as Burning Spear, Toots and the Maytals, and the Wailers. In honor of the 20th anniversary of Dodd’s passing, learn about 10 of his greatest productions.

On April 30, 2004, producer Clement Seymour "Sir Coxsone" Dodd — an architect in the construction of Jamaica’s recording industry — was honored at a festive street renaming ceremony on Brentford Road in Kingston, Jamaica. The bustling, commercial thoroughfare at the geographical center of Kingston was rechristened Studio One Blvd. in recognition of Coxsone’s recording studio and record label.

Dodd is said to have acquired a former nightclub at 13 Brentford Road in 1962; his father, a construction worker, helped him transform the building into the landmark studio. In 1963 Dodd installed a one-track board and began recording and issuing records on the Studio One label.

Dodd’s Studio One was Jamaica’s first Black-owned recording facility and is regarded as Jamaica’s Motown because of its consistent output of hit records. Studio One releases helped launch the careers of numerous ska, rocksteady and reggae legends including Bob Andy, Dennis Brown, Burning Spear, Alton Ellis, the Gladiators, the Skatalites, Toots and the Maytals, Marcia Griffiths, Sugar Minott, Delroy Wilson and most notably, the Wailers.

At the street renaming ceremony, a jazz band played, speeches were given in tribute to Dodd’s immeasurable contributions to Jamaican music and many heartfelt memories from the studio’s heyday were shared. In the culmination of the late afternoon program, Dodd, his wife Norma, and Kingston’s then mayor Desmond McKenzie unveiled the first sign bearing the name Studio One Blvd. Four days later, on April 4, 2002, Coxsone Dodd suffered a fatal heart attack at Studio One. His productions, however, live on as benchmarks within the island’s voluminous and influential music canon.

Born Clement Seymour Dodd on Jan. 26, 1932, he was given the nickname Sir Coxsone after the star British cricketer whose batting skills Clement was said to match. As a teenager, Dodd developed a fondness for jazz and bebop that he heard beamed into Jamaica from stations in Miami and Nashville and the big band dances he attended in Kingston. Dodd launched Sir Coxsone’s Downbeat sound system around 1952 with the impressive collection of R&B and jazz discs he amassed while living in the U.S., working as a seasonal farm laborer.

Many sound system proprietors traveled to the U.S. to purchase R&B records — the preferred music among their dance patrons and key to a sound system’s following and trumping an opponent in a sound clash. With the birth of rock and roll in the mid-1950s, suitable R&B records became scarce. Jamaica’s ever-resourceful sound men ventured into Kingston studios to produce R&B shuffle recordings for sound system play.

Recognizing there was a wider market for this music, Dodd pressed up a few hundred copies of two sound system favorites for general release, the instrumental "Shuffling Jug" by bassist Cluett Johnson and his Blues Blasters and singer/pianist Theophilus Beckford’s "Easy Snapping," both issued on Dodd’s first label, Worldisc. (Some historians recognize "Easy Snapping" as a bridge between R&B shuffle and the island’s Indigenous ska beat; others cite it as the first ska record.) When those discs sold out within a few days, other soundmen followed Dodd’s lead and Jamaica’s commercial recording industry began to flourish.

"Before then, the only stuff released commercially were mento records that were recorded here, but our sound really hit so we kept on recording. When I heard 'Easy Snapping,' I said 'Oh my gosh!'" Coxsone recalled in a 2002 interview for Air Jamaica's Skywritings at Kiingston’s Studio One. "I thank God for that moment."

Dodd was the first producer to enlist a house band, pay them a weekly salary rather than per record. Together, they had an impressive run of hits in the ska era in the early ‘60s; during the rocksteady period later in the decade, Dodd ceded top ranking status to long standing sound system rival (but close family friend) turned producer Duke Reid. (Still, Studio One released the most enduring instrumentals or rhythm tracks, also known as riddims, of the period.) As rocksteady morphed into reggae circa 1968, Dodd triumphed again with consistent releases of exceptional quality.

In 1979 armed robbers targeted the Brentford Rd premises several times. Dodd left Jamaica and established Coxsone’s Music City record store/recording studio in Brooklyn, dividing his time between New York and Kingston. Reissues of Dodd’s music via Cambridge, MA based Heartbeat Records, beginning in the mid 1980s, followed by London’s Soul Jazz label in the 2000s, and most recently Yep Roc Records in Hillsborough, NC, have helped introduce Studio One’s masterful work to new generations of fans.

"The best time I’ve ever had was when I acquired my studio at 13 Brentford Rd. because you can do as many takes until we figured that was it," Coxsone reflected in the 2002 interview. "God gave me a gift of having the musicians inside the studio to put the songs together. In the studio, I always thought about the fans, making the music more pleasing for listening or dancing. What really helped me was having the sound system, you play a record, and you weren’t guessing what you were doing, you saw what you were doing."

To commemorate the 20th anniversary of Coxsone Dodd’s passing, read on for a list of 10 of his greatest productions.

The Maytals - "Six and Seven Books of Moses" (1963)

In 1961 at the dawn of Jamaica’s ska era, Toots Hibbert met singers Nathaniel "Jerry" Matthias and Henry "Raleigh" Gordon and they formed the Maytals. The trio released several hits for Dodd including the rousing, "Six and Seven Books of Moses," a gospel-drenched ska track that’s essentially a shout out of a few Old Testament chapters.

Moses is credited with writing five chapters, as the lyrics state, "Genesis and Exodus, Leviticus and Numbers Deuteronomy," but "the Six and Seven books" are in question. Many Biblical scholars say Moses wasn’t the scribe, believing those chapters, including phony spells and incantations to keep evil spirits away, were penned in the 18th or 19th century.

Nevertheless, there’s a real magic formula in The Maytals’ "Six and Seven Books of Moses": Toots’ electrifying preacher at the pulpit delivery melds with elements of vintage soul, gritty R&B, and classic country; Jerry and Raleigh provide exuberant backing vocals and seminal ska outfit and Studio One’s first house band, the Skatalities deliver an irresistible, jaunty ska rhythm with a sophisticated jazz underpinning.

The Wailers - "Simmer Down" (1964)

A flashback scene in the biopic Bob Marley: One Love depicts the Wailers (then a teenaged outfit called the Juveniles) approaching Dodd for a recording opportunity; Dodd inexplicably points a gun at them as they recoil in terror. Yet, there isn’t any mention of such an inappropriate and unprovoked action from the producer in the various books, documentaries, interviews and other accounts of the Wailers’ audition for Dodd.

The Wailers’ first recording session with Dodd in July 1964, however, yielded the group’s first hit single "Simmer Down." At that time, the Wailers lineup consisted of founding members Bob Marley, Bunny Livingston (later Wailer) and Peter Tosh alongside singers Junior Braithwaite and (the sole surviving member) Beverley Kelso. When Junior left for the U.S., Dodd appointed Marley as the group’s lead singer.

The energetic "Simmer Down" cautions the impetuous rude boys to refrain from their hooligan exploits. The Skatalites’ spirited horn led intro, thumping jazz infused bass and fluttering sax solo, enhances Marley’s youthful lead and the backing vocalists’ effervescence. The Wailers would spend two years at Studio One and record over 100 songs there, including the first recording of "One Love" in 1965; by early 1966, they would have five songs produced by Dodd in the Jamaica Top 10.

Alton Ellis -"I’m Still In Love" (1967)

Jamaica’s brief rocksteady lasted about two years between 1966-1968, but was an exceptionally rich and influential musical era. The rocksteady tempo maintained the accentuated offbeat of its ska predecessor, but its slower pace allowed vocal and musical arrangements, affixed in heavier, more melodic basslines.

Alton Ellis is considered the godfather of rocksteady because he had numerous hits during the era and released "Rock Steady," the first single to utilize the term for producer Duke Reid. Ellis initially worked with Dodd in the late 1950s then returned to him in 1967. The evergreen "I’m Still in Love" was penned by Alton as a plea to his wife as their marriage dissolved: "You don’t know how to love me, or even how to kiss me/I don’t know why." Supporting Alton’s elegant, soulful rendering of heartbreak, Studio One house band the Soul Vendors, led by keyboardist Jackie Mittoo, provide an engaging horn-drenched rhythm, epitomizing what was so special about this short-lived time in Jamaican music.

"I’m Still In Love" has been covered by various artists including Sean Paul and Sasha, whose rendition reached No. 14 on the Billboard Hot 100 in 2004. Beyoncé utilized Jamaican singer Marcia’s Aitken’s 1978 version of the tune in a TV ad announcing her 2018 On The Run II tour with Jay-Z. In February 2024, Jennifer Lopez sampled "I’m Still in Love" for her single "Can’t Get Enough."

Bob Andy - "I’ve Got to Go Back Home" (1967)

The late Keith Anderson, known professionally as Bob Andy, arrived at Studio One in 1967. He quickly became a hit-making vocalist, and an invaluable writer for other artists on the label. He penned several hits for Marcia Griffiths including "Feel Like Jumping," "Melody Life" and "Always Together," the latter their first of many hit recordings as a duo.

A founding member of the vocal trio the Paragons, "I’ve Got to go Back Home" was Andy’s first solo hit and it features sublime backing vocals by the Wailers (Bunny, Peter and Constantine "Vision" Walker; Bob Marley was living in the USA at the time.) Set to a sprightly rock steady beat featuring Bobby Ellis (trumpet), Roland Alphonso (saxophone) and Carlton Samuels’ (saxophone) harmonizing horns, Andy’s lyrics poignantly depict the challenges endured by Jamaica’s poor ("I can’t get no clothes to wear, can’t get no food to eat, I can’t get a job to get bread") while expressing a longing to return to Africa, a central theme within 1970s Rasta roots reggae.

The depth of Andy’s lyrics expanded the considerations of Jamaican songwriters and one of his primary influences was Bob Dylan. "When I heard Bob Dylan, it occurred to me for the first time that you don’t have to write songs about heart and soul," Andy told Billboard in 2018. "Bob Dylan’s music introduced me to the world of social commentary and that set me on my way as a writer."

Dawn Penn - "You Don’t Love Me" (1967)

Dawn Penn’s plaintive, almost trancelike vocals and the lilting rock steady arrangement by the Soul Vendors transformed Willie Cobbs’ early R&B hit "You Don’t Love Me," based on Bo Diddley’s 1955 gritty blues lament "She’s Fine, She’s Mine," into a Jamaican classic. The song’s shimmering guitar intro gives way to the forceful drum and bass with Mittoo’s keyboards providing an understated yet essential flourish.

In 1992 Jamaica’s Steely and Clevie remade the song, featuring Penn, for their album Steely and Clevie Play Studio One Vintage. The dynamic musician/production duo brought their mastery (and 1990s technological innovations) to several Studio One classics with the original singers. Heartbeat released "You Don’t Love Me" as a single and it reached No. 58 on the Billboard Hot 100.

Several artists have reworked Penn’s rendition or sampled the Soul Vendors’ arrangement including rapper Eve on a collaboration with Stephen and Damian Marley. Rihanna recruited Vybz Kartel for an interpretation included on her 2005 debut album Music of the Sun, while Beyoncé performed the song on her I Am world tour in 2014 and recorded it in 2019 for her Homecoming: The Live Album. In 2013, Los Angeles-based Latin soul group the Boogaloo Assassins brought a salsa flavor to Penn's tune, creating a sought-after DJ single.

The Heptones - "Equal Rights" (1968)

"Every man has an equal right to live and be free/no matter what color, class or race he may be," sings an impassioned Leroy Sibbles on "Equal Rights," the Heptones’ stirring plea for justice.

Harmony vocalist Earl Morgan formed the group with singer Barry Llewellyn in the early '60s and Sibbles joined them a few years later. The swinging bass line, played by Sibbles, anchors a stunning rock steady rhythm track awash in cascading horns, and blistering percussion patterns akin to the akete or buru drums heard at Rastafari Nyabinghi sessions.

Besides leading the Heptones’ numerous hit singles during their five-year stint at Studio One, Sibbles was a talent scout, backing vocalist, resident bassist and the primary arranger, alongside Jackie Mittoo. Sibbles’ progressive basslines are featured on numerous Studio One nuggets (many appearing on this list) and have been sampled or remade countless times over the decades on Jamaican and international hits.

In a December 2023 interview Sibbles echoed a complaint expressed by many who worked at Studio One: Dodd didn’t fairly compensate his artists and the (uncredited) musicians produced the songs while Dodd tended to business matters. "When we started out, we didn’t know about the business, and what happened, happened. But as you learn as you go along," he said. "I have registered what I could; I am living comfortably so I am grateful."

The Cables - "Baby Why" (1968)

Formed in 1962 by lead singer Keble Drummond and backing vocalists Vincent Stoddart and Elbert Stewart, the Cables — while not as well-known as the Wailers, the Maytals or the Heptones — recorded a few evergreen hits at Studio One, including the enchanting "Baby Why."

Keble’s aching vocals lead this breakup tale as he warns the woman who left that she’ll soon regret it. The simple story line is delivered via a gorgeous melody that’s further embellished by Vincent and Elbert’s superb harmonizing, repeatedly cooing to hypnotic effect "why, why oh, why?"

Coxsone is said to have kept the song for exclusive sound system play for several months; when he finally released it commercially, "Baby Why" stayed at No. 1 for four weeks.

"Baby Why" is notable for another reason: although the Maytals’ "Do The Reggay" marks the initial use of the word reggae in a song, "Baby Why" is among a handful of songs cited as the first recorded with a reggae rhythm (reggae basslines are fuller and reggae’s tempo is a bit slower than its rocksteady forerunner.) Other contenders for that historic designation include Lee "Scratch Perry’s "People Funny Boy," the Beltones’ "No More Heartache," and Larry Marshall and Alvin Leslie’s delightful "Nanny Goat."

Burning Spear - "Door Peeper" (1969)

Hailing from the parish of St. Ann, Jamaica, Burning Spear was referred to Studio One by another St. Ann native, Bob Marley. Spear’s first single for Studio One "Door Peeper" (also known as "Door Peep Shall Not Enter") recorded in 1969, sounded unlike any music released by Dodd and was critical in shaping the Rastafarian roots reggae movement of the next decade.

The song’s biblically laced lyrics caution informers who attempt to interfere with Rastafarians, considered societal outcasts at the time in Jamaica, while Spear’s intonation to "chant down Babylon" creates a haunting mystical effect, supported by Rupert Willington’s evocative, deep vocal pitch, a throbbing bass, mesmeric percussion and magnificent horn blasts.

As Spear told GRAMMY.com in September 2023, "When Mr. Dodd first heard 'Door Peep' he was astonished; for a man who’d been in the music business for so long, he never heard anything like that." Dodd’s openness to recording Rasta music, and allowing ganja smoking on the premises (but not in the studio) when his competitors didn’t put him in the forefront at the threshold of the roots reggae era.

"Door Peeper" was included on Burning Spear’s debut album, Studio One Presents Burning Spear, released in 1973 and remains a popular selection in the legendary artist’s live sets.

Joseph Hill - "Behold The Land" (1972)

In the October 1946 address Behold The Land by W. E. B. DuBois at the closing session of the Southern Youth Legislature in Columbia, South Carolina, the then 78-year-old celebrated author and activist urges Black youth to fight for racial equality and the civil rights denied them in Southern states. The late Joseph Hill’s 1972 song of the same name, possibly influenced by Dubois’ words, is a powerful reggae missive exploring the atrocities of the transatlantic slave trade from which descended the discriminations DuBois described.

Hill was just 23 when he wrote/recorded "Behold The Land," his debut single as a vocalist. Hill’s haunting timbre summons the harrowing experience with the wisdom and emotional rendering of an ancestor: "For we were brought here in captivity, bound in links and chains and we worked as slaves and they lashed us hard." Hill then gives praise and asks for repatriation to the African motherland, "let us behold the land where we belong."

The Soul Defenders — a self contained entity but also a Studio One house band with whom Hill made his initial recordings as a percussionist — provide a persistent, bass heavy rhythm that suitably frames Hill’s lyrical gravitas, as do the melancholy hi-pitched harmonies.

In 1976 Hill formed the reggae trio Culture and the next year they catapulted to international fame with their apocalyptic single "Two Sevens Clash," which prompted Dodd to finally release "Behold The Land." Culture would re-record "Behold The Land" over the years including for their 1978 album Africa Stand Alone and the song received a digital remastering in 2001.

Sugar Minott - "Oh Mr. DC" (1978)

In the mid-1970s singer Lincoln "Sugar" Minott began writing lyrics to classic 1960s Studio One riddims, an approach that launched his hitmaking solo career and further popularized the practice of riddim recycling — which is still a standard approach in dancehall production. Sugar, formerly with the vocal trio The African Brothers, penned one of his earliest solo hits "Oh, Mr. DC" to the lively beat of the Tennors’ 1967 single "Pressure and Slide" (itself a riddim originally heard, at a faster pace, underpinning Prince Buster’s 1966 "Shaking Up Orange St.")

"Oh, Mr. DC" is an authentic tale of a ganja dealer returning from the country with his bag of collie (marijuana); the DC (district constable/policeman) says he’s going to arrest him and threatens to shoot if he attempts to run away. Sugar explains to the officer that selling herb is how he supports his family: "The children crying for hunger/ I man a suffer, so you’ve got to see/it’s just collie that feed me." To underscore his urgent plea, Sugar wails in an unforgettable melody, "Oh, oh DC, don’t take my collie."

The irresistibly bubbling bassline of the riddim nearly obscures the song’s poignant depiction of Jamaica’s harsh economic realities and the potential risk of imprisonment, or worse, that the island’s ganja sellers faced at the time. Sugar’s revival of a Studio One riddim and reutilization of 10 Studio One riddims for each track of his 1977 album Live Loving brought renewed interest to the treasures that could be extracted from Mr. Dodd’s vaults.

Special thanks to Coxsone Dodd’s niece Maxine Stowe, former A&R at Sony/Columbia and Island Records, who started her career at Coxsone’s Music City, Brooklyn.

How 'The Harder They Come' Brought Reggae To The World: A Song By Song Soundtrack Breakdown

Photo: Jeff Kravitz/FilmMagic

video

GRAMMY Rewind: Kendrick Lamar Honors Hip-Hop's Greats While Accepting Best Rap Album GRAMMY For 'To Pimp a Butterfly' In 2016

Upon winning the GRAMMY for Best Rap Album for 'To Pimp a Butterfly,' Kendrick Lamar thanked those that helped him get to the stage, and the artists that blazed the trail for him.

Updated Friday Oct. 13, 2023 to include info about Kendrick Lamar's most recent GRAMMY wins, as of the 2023 GRAMMYs.

A GRAMMY veteran these days, Kendrick Lamar has won 17 GRAMMYs and has received 47 GRAMMY nominations overall. A sizable chunk of his trophies came from the 58th annual GRAMMY Awards in 2016, when he walked away with five — including his first-ever win in the Best Rap Album category.

This installment of GRAMMY Rewind turns back the clock to 2016, revisiting Lamar's acceptance speech upon winning Best Rap Album for To Pimp A Butterfly. Though Lamar was alone on stage, he made it clear that he wouldn't be at the top of his game without the help of a broad support system.

"First off, all glory to God, that's for sure," he said, kicking off a speech that went on to thank his parents, who he described as his "those who gave me the responsibility of knowing, of accepting the good with the bad."

Looking for more GRAMMYs news? The 2024 GRAMMY nominations are here!

He also extended his love and gratitude to his fiancée, Whitney Alford, and shouted out his Top Dawg Entertainment labelmates. Lamar specifically praised Top Dawg's CEO, Anthony Tiffith, for finding and developing raw talent that might not otherwise get the chance to pursue their musical dreams.

"We'd never forget that: Taking these kids out of the projects, out of Compton, and putting them right here on this stage, to be the best that they can be," Lamar — a Compton native himself — continued, leading into an impassioned conclusion spotlighting some of the cornerstone rap albums that came before To Pimp a Butterfly.

"Hip-hop. Ice Cube. This is for hip-hop," he said. "This is for Snoop Dogg, Doggystyle. This is for Illmatic, this is for Nas. We will live forever. Believe that."

To Pimp a Butterfly singles "Alright" and "These Walls" earned Lamar three more GRAMMYs that night, the former winning Best Rap Performance and Best Rap Song and the latter taking Best Rap/Sung Collaboration (the song features Bilal, Anna Wise and Thundercat). He also won Best Music Video for the remix of Taylor Swift's "Bad Blood."

Lamar has since won Best Rap Album two more times, taking home the golden gramophone in 2018 for his blockbuster LP DAMN., and in 2023 for his bold fifth album, Mr. Morale & the Big Steppers.

Watch Lamar's full acceptance speech above, and check back at GRAMMY.com every Friday for more GRAMMY Rewind episodes.

10 Essential Facts To Know About GRAMMY-Winning Rapper J. Cole