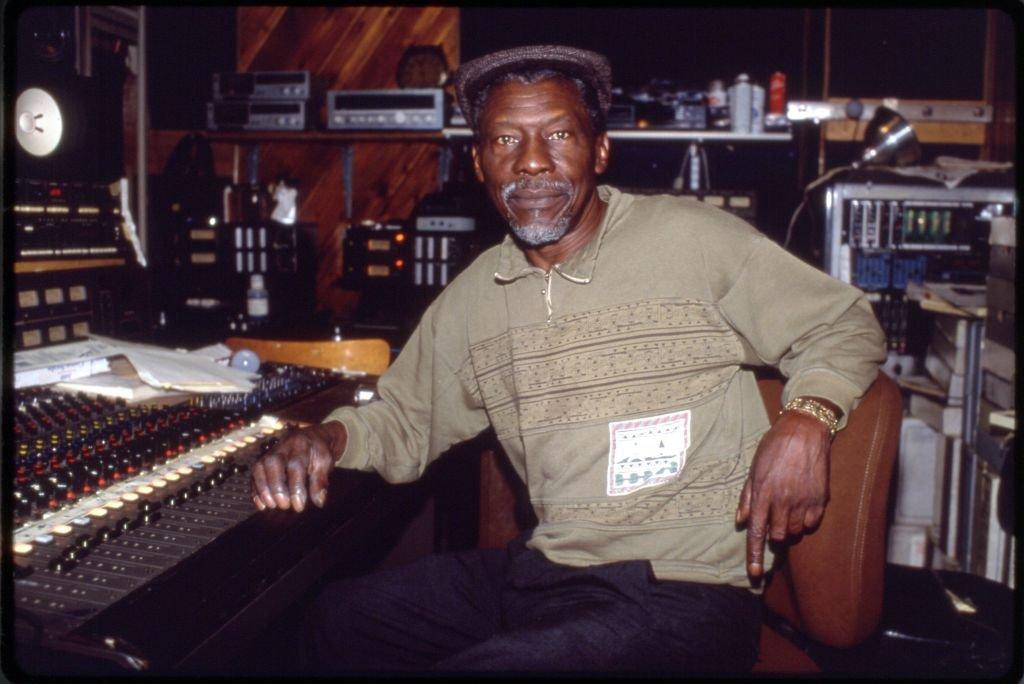

Photo: Paul Bergen/Redferns/Getty Images

Lee "Scratch" Perry in 2018

interview

Lee "Scratch" Perry Documentary Director Sets The Record Straight On The Reggae Icon's Legacy — Including A Big Misconception About Bob Marley

'The Upsetter: The Life and Music of Lee Scratch Perry,' a documentary that showcases the reggae pioneer's eccentricity, first debuted in 2008. Now streaming on Criterion Collection, co-director Adam Bhala Lough details his experience capturing a legend.

Lee "Scratch" Perry, one of the giants of reggae music, is known as the Upsetter. His musical creations, for both himself and others, upended the sound of Jamaican music and reverberated around the world for multiple generations.

"To upset people, uplift the people, and another part means to destroy them. The word can do anything; it's a two edges sword," Perry says in The Upsetter: The Life and Music of Lee Scratch Perry, a 2008 documentary now streaming for the first time through the Criterion Collection. Putting Perry's particular brand of genius on display, the documentary is an art piece that attempts to capture the eccentric (and sometimes mad) energy of one of reggae's greatest minds.

"People just think he was this crazy guy who's in the lab making these crazy songs," Adam Bhala Lough, who co-directed the film with Ethan Higbee, tells GRAMMY.com. "But no, he's a musical genius, a music historian, an art historian, a really brilliant mind."

Prior to his death in August 2021 at age 85, Perry was nominated for five GRAMMYs and won Best Reggae Album at the 2003 GRAMMY Awards. The Upsetter serves as something of a time capsule, capturing Perry on the verge as he returns from self-imposed obscurity and isolation to performance.

A country boy, Perry moved to Kingston, Jamaica in the early 1960s and gravitated toward the city's exploding ska scene. He worked at the three major recording houses — owned by pioneers Coxsone Dodd, Duke Reid and Prince Buster — working his way up from janitor to producer and, often, uncredited songwriter. Eventually, Perry became his own musical force with a band, label and record shop.

In addition to hits for his own group — his house band, the Upsetters— Perry created hits for a young Bob Marley and the Wailers and was majorly responsible for getting the Wailers to a global stage. Perry also produced Marley as a solo act, giving him the courage and content to become a legend. At his height, Perry produced 20 songs a week for hundreds of artists, including Burning Spear and Jimmy Cliff, for five years straight.

From his home studio the Black Ark, Perry invented dub music — a genre of reggae that would serve as the forebearer to all modern electronic music. Utilizing the mixing board as an instrument, Perry pioneered manipulating sound by removing vocals, emphasizing drum and bass, and adding effects. Singers and DJs would "toast" (talk and sing in rhythm) over Perry's instrumental tracks, a style that would take flight to New York via Jamaican immigrants and form the basis of hip-hop.

Read More: Remembering Reggae Legend Lee "Scratch" Perry, The Dub Afrofuturist

Yet, a series of unfortunate occurrences — including a falling out with the group of Rastafarians living at the Ark; numerous people attempting to hustle Perry for his money; and a devastating fire at the Ark, which Perry himself set — culminated in Perry's descent into what some may call madness. The Upsetter captures much of that energy, giving ample space to Perry's rambling speeches while imbuing much of the film with a psychedelic overtone.

"We made this pretty radical decision to just give space to Lee to tell his story, whether it was factual or unfactual," says Bhala Lough. "To me, it's vitally important that if you have that type of access, you give space to that voice."

The documentary ends in 2006, 15 years before Perry passed. While much happened in that last decade-plus of his life, The Upsetter ends triumphantly, with Perry returning to the stage after a multi-year hiatus from performing. Told in his own words — with minor narration from Oscar-winning director Benicio del Toro, "the biggest Lee Perry fan in Hollywood," according to Bhala Lough — the film is an attempt to capture a peculiar, prolific man whose influence far outlasts his lifetime.

Ahead of its streaming debut on Criterion, GRAMMY.com spoke with Bhala Lough to to discuss Lee "Scratch" Perry's music, idiosyncrasies and the need to decolonize reggae music.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

What was your thought process constructing this documentary? It's just Lee, in his own words, and I was kind of expecting interviews with other people.

That was a specific choice we made very early on. We only wanted Lee's voice in the film; we wanted Lee to tell his story. We really felt like the history of reggae has been, in a way, hijacked by a white perspective. It comes from such a painfully colonialist perspective. We actually went and interviewed tons of these people — from Adrian Sherwood to Chris Blackwell — as research in a way. But we just had no interest in trotting out the white man to tell the story or even comment on Lee.

I think that the Caribbean voice, the Afro-Caribbean voice, is often kind of forgotten in the story of Black history. So to have an opportunity to have a Jamaican man tell his story, the way that he lived it — whether it's correct or incorrect, or, you know, revisionist, or whatever — is, I think, a duty of a filmmaker.

What was the filming process like?

We got in touch with Lee and he basically said, "Listen, I'll do it, but you need to bring me a shoe box with $5,000 cash in it." So Ethan [Higbee, his co-director] got the advance from this Argentinian trucking company and went to London. Ethan was thinking he was going to have a normal meeting with Lee, but he ended up at a dinner with Lee and all of Lee's ex wives and all their children. [Laughs.]

He gave him the box and Lee gave him his address in Switzerland, where he was living at the time. We showed up on his doorstep — we had no way to contact him, so it wasn't like he knew we were coming. He didn't do email, he didn't text. There was a landline, but never no one ever answered it.

Day one, we pulled up, he recognized us, and he was ready to go. We spent eight days there at the house with him [in 2003 or 2004], just filming around the clock. By the end of it, we felt like part of the family. We had dinner with his wife and children every night.

We also had arrived at a very good time; he had just gone sober. Completely sober — no weed, no alcohol, no nothing. And he was very much ready to tell his story. So it was very much like a fortuitous arrival. As you can see in the film, we just kind of continued to pop in and out and travel around with him for the next, like, five or six years.

It also seems like you guys operated in the same way he did at his legendary studio in Jamaica, the Black Ark — just hanging out, coming and going as you please, creating 24/7. Did it feel like that to you at all?

That was definitely the whole vibe. And it was really quite thrilling.

Lee is eccentric, to say the least, and I felt a little unhinged watching parts of the documentary. Was that intentional?

Lee, I think, was an eccentric man from birth. I think that he played the role of a madman to a large degree to keep people away from him.

We wanted the film to be both historical and biographical, and experiential in the sense that it was almost impressionistic. At some point, the film started to become mad, in a way, in the same way he did. The process of making it was very much like a collage. It is an art piece.

I think it was misunderstood when it came out. People were very much expecting a traditional bio doc from a white European perspective, very bland VH1 style. It should be seen more as a weirdo art piece that you would stumble upon on cable access at midnight when you're drunk and stoned.

What do people misunderstand about Lee, or misconstrue, that your film best highlights?

The number one misunderstanding, that hopefully we can correct, is this idea that Chris Blackwell made Bob Marley famous and put Bob Marley on; that the American and English recording industry made Bob Marley. This is a complete fabrication of the truth. The fact is, Lee Perry made Bob Marley.

I'll watch these docs and read books [about Bob Marley] … and Lee may be mentioned in a half a chapter or there's one interview. Everything else is about how a white man came down to Jamaica and discovered him, and then another white man and America put him on and made him famous. It is such bullshit. Lee Perry created Bob Marley.

"Dreadlocks in Moonlight" — which I think is Lee's greatest song — he wrote that for Bob and he voiced it for Bob. It was actually a vocal track that Lee just put down for Bob to copy. When [Marley] heard it, he was so emotionally riveted by it that he's like, "Dude, you need to just release this yourself."

Bob would copy [Lee's] flow, the voice. We talked to some people in Jamaica, engineers and stuff like that, who couldn't tell the difference between Bob and Lee's voice at some points.

It seems that Lee was kind of tortured by his relationship with Bob over the years, because it was so up and down. Is that accurate?

I don't know if Lee would agree with that. Bob obviously got so big, and Lee would say Bob was kidnapped by the white devil — which is an extreme exaggeration, but that's how Lee would talk.

But there is something to it, right? Bob was kidnapped by a white, American, European establishment in some ways. So I think that obviously alienated Lee, because Lee would have no part of that.

Lee seems to be a bit wild, that he likes to egg people on. That final scene in the store in San Francisco, where he gets into a confrontation with a customer, was a bit confusing to me. To be honest, I'm not sure what happened or why you decided to include it in the film.

It was so unnerving; I honestly thought we were gonna have to put the cameras down and fight this guy. The guy was a racist — he was one step away from like, using the N word.

Lee is like a king, right? He's like this little king walking around with his crew and this white man just could not handle it. This is, undoubtedly, something that had probably happened to Lee hundreds of times.

Being a successful Black man who sticks out like a sore thumb — he has red hair, rings on every finger, 67 years old — he draws a lot of negative attention. He would say that he would draw out the devil. Like, evil would come for him wherever he went just as much as good.

Is there anything about Lee that differentiates him from other artists of his generation, or others in his field?

One thing about Lee that I think people overlook is just how brilliant he was. There are certain things he would do that would [make you think] he's a madman, but then he will start talking about music history, Black music history, in such a way that you're like, oh my god, he knows everything. He's very studied; his whole genius is deliberate.

People just think he was this crazy guy who's in the lab making these crazy songs. But no, he's a musical genius, a music historian, an art historian, a really brilliant mind. I think that if somebody had given him an IQ test, that would have been off the charts. He didn't really show people that side.

The Upsetter ends in 2007, but you stayed in touch with Lee through the years until his death in 2021. How did Lee evolve, if at all, during that time?

Like anyone, he softened up over the years. There was a certain way that he acted around white people that was very different than he acted around Jamaicans. If it was all Jamaicans in a room, and then us with cameras, he was very much a tough guy. I mean, I can only imagine what he went through, coming to Kingston from the country and trying to make it in the music industry. He got in a lot of physical confrontations, and he had a lot of guns stuck in his face. He definitely had kind of a thuggish persona that would come out.

The last time I saw him, he was just a big teddy bear. He was doing a live painting in Ethan's Gallery in West Hollywood and [we brought] our children, who were toddlers at the time. He had all the children painting with him.

There has been a fair amount of work about Lee "Scratch" Perry since the release of your documentary. What do you think makes your film unique and continue to be relevant?

The interview that we did with Lee at the time in his life, where he was really ready to talk, has great historical significance and will decades into the future.

The really sad thing is that Ethan's house burned to the ground in the Thomas Fire a couple years ago and we lost everything — all the mini DV tapes of that interview of that eight days, all gone.

Lastly, how did Benicio Del Toro come to narrate the documentary?

Ethan was Ryan Phillippe’s driver for the movie Crash and they became buddies. [Ethan] would play Lee Perry in the car and Ryan was like, "What's up with the Lee Perry music?" Ethan's like, "I'm doing this documentary," and Ryan was like, "You need to talk to Benicio Del Toro, he’s the biggest Lee Perry fan in Hollywood." Ryan put us in touch with Benicio and that was it.

[Benicio] rewrote all the narration, which we thought was really cool. He was so into the film; he had really studied it. We had no expectations, but since then, he's been such a great champion of the film. It's one of the few things that he loves to talk about — and that means a lot to us.

Photos: Courtesy of the artist; Johnny Louis/Getty Images; Courtesy of the artist; Yannick Reid; Horace Freeman; Courtesy of the artist

list

10 Artists Shaping Contemporary Reggae: Samory I, Lila Iké, Iotosh & Others

In honor of Caribbean American Heritage Month, meet 10 artists who are shaping the sound of contemporary reggae. From veterans who are hitting great strides, to promising newcomers, these acts showcase reggae's wide appeal.

The result of audacious experimentation by studio musicians and producers, reggae originated in Jamaica circa 1968 in Kingston, Jamaica. Along with its various subgenres of lovers rock, roots, dub and dancehall, reggae has influenced many music forms and found adoring audiences all over the world.

An authentic expression of the singers and musicians’ surroundings and experiences, reggae evolved from its 1960s forerunners, ska and rocksteady, shaped by contemporary influences such as American jazz and R&B, and mento, Jamaican folk music. Likewise, today’s reggae music makers draw from genres such as hip-hop (especially its trap strain) to create a generationally distinctive sound that still remains tethered to Jamaica's musical history.

In the 2020s, the Best Reggae Album GRAMMY winners reflect the diverse musical palette that comprises contemporary reggae. EDM influences and reggaeton (a genre built upon digitized dancehall reggae riddims) remixes dominate the 2024 winner Julian Marley and Antaeus' Colors of Royal. The award’s 2023 recipient — Kabaka Pyramid's The Kalling, produced by Damian and Stephen Marley — intertwines traditional roots reggae with Kabaka’s love of hip-hop. The late, great Toots Hibbert was posthumously awarded the 2021 GRAMMY for Time Tough, a hard rocking, R&B influenced gem that captured Toots’ soulful exuberance. In 2020 Koffee became the youngest and first female awardee in the category for Rapture, which features the most experimental soundscapes among this decade’s winners. Ironically, the most traditional approach to reggae is heard on American reggae band SOJA’s 2022 winner, Beauty in the Silence.

Read more: Lighters Up! 10 Essential Reggae Hip-Hop Fusions

In honor of Caribbean American Heritage Month, which was officially designated by a Presidential proclamation in June 2006, here are 10 Jamaican artists who are shaping contemporary reggae. Some are veterans who are currently hitting the greatest strides of their professional lives, others are newcomers at the threshold of extremely promising careers. All are committed to their craft and upholding reggae, even if their music ocassionally sounds unlike the reggae of a generation ago.

Kumar Bent (and the Original Fyah)

In the mid 2010s, Jamaican band Raging Fyah had a significant impact on the American reggae circuit, with their burnished, inspirational roots reggae brand as heard on such songs as "Nah Look Back" and "Judgement Day." They toured the U.S. with American reggae outfits including Stick Figure, Iration and Tribal Seeds, and supported Ali Campbell’s version of UB40 in the UK. Raging Fyah’s album Everlasting was nominated for a 2017 Best Reggae Album GRAMMY.

The following year, charismatic lead singer and principal songwriter Kumar Bent (along with guitarist Courtland "Gizmo" White, who passed away in 2023) left due to differences with their bandmates.

In 2023 Kumar teamed up with Raging Fyah alumni, drummer Anthony Watson, keyboardist Demar Gayle and backing vocalist/engineer Mahlon Moving to create The Original Fyah. In February they performed at the band’s annual Wickie Wackie festival in Jamaica and they’ve recorded an album due for upcoming release (Demar has since moved on to other projects.)

Kumar, 35, a classically trained pianist, has recorded two solo albums, including Tales of Reality with Swiss studio band 18th Parallel; they’ll tour Europe together in October. Kumar’s acoustic guitar sets have opened several dates for stalwart Jamaican band Third World this year.

Each of his musical endeavors are focused on bolstering Jamaica’s signature rhythm.

"Reggae from the 1970s and ‘80s was special because Jamaican artists made the songs exactly how they felt, and found an audience with the sounds they created," Kumar tells GRAMMY.com. "If we (Jamaicans) keep making R&B, hip-hop sounding music, we are giving away what we have for something else that we are not as good at."

Lila Iké

Lila Iké's multifarious influences run deep. "I am a Jamaican artist who is influenced by different music and you’re going to hear that coming through," she said in a June 2020 interview with The Daily Beast, following the release of her debut EP The ExPerience.

While Jamaican music expanded beyond what Iké called "the purist reggae vibe," she told The Daily Beast that "it’s important to maintain the music’s indigenousness. I incorporate that into the rhythms I use and my singing style because I want young people to know, this music doesn’t start where you hear it, it has transcended many years and changes."

Born Alecia Grey, she chose the name Lila, which means blooming flower, and Iké, a Yoruba word meaning the Power of God. Her vocals are a singular, mesmerizing blend of smoky, soulful expressions with a laid back yet poignant rendering. Lila’s effortless versatility is rooted in her upbringing in the rural community of Christiana. Her mother listened to a wide range of music, R&B, jazz, soul, country and reggae, with Lila, her mom and sisters singing along to all of it.

Lila moved to Kingston to pursue her musical ambitions; she performed on open mic nights and posted her songs on social media. Protoje reached out to her via Twitter with an invitation to record. From that initial meeting, Protoje has managed and mentored her career. Through his label In.Digg,Nation Collective’s deal with RCA Records, Lila will release her debut album later this year; Protoje also produced the album’s first single, the reggae/R&B slow jam duet "He Loves Us Both" featuring H.E.R.

Hezron

A passionate singer whose vocals marry the grit of Otis Redding with the cool of Marvin Gaye, singer/songwriter and musician Hezron has yet to achieve the widespread impact his talents merit, although he's been planting seeds since 2010. That year, his single "So In Love" was the first of Hezron's substantial musical fruits and exceptional catalog.

On his 2022 self-produced, remarkable album Man on a Mission, Hezron explores a range of Jamaican music and history. On the rousing ska track "Plant A Seed," Hezron's guttural, gospel inflected delivery is reminiscent of Toots Hibbert as he warns his critics, "You think you bury me and done but you only planted a seed." The album also features a scorching R&B jam "Tik Tok I’m Coming"; an acoustic, mystical acknowledgement of Rastafari, "Walk In Love and Light"; and a stirring plea to "Save The Children." The album’s title track is a spirited reggae anthem offering support to anyone in pursuit of their goals while underscoring Hezron’s own purpose.

"Man on a Mission is about my personal journey, the obstacles I’ve had to overcome in the music business and beyond. I’m telling myself, telling the world, this man is on a mission to restore Jamaican music to a prominent place internationally," Hezron tells GRAMMY.com.

In November 2023 Hezron embarked on a global mission: a two-month tour of Ghana, followed, this year, by summer shows in Canada and the U.S. before returning to Africa, with dates in Ivory Coast, Kenya, and South Africa.

Iotosh

A self-taught multi-instrumentalist, songwriter and vocalist, Iotosh (born Iotosh Poyser) made his name as a producer who can seamlessly blend disparate influences into progressive reggae soundscapes. He’s produced singles for several marquee acts who emerged from Jamaica’s reggae revival movement of the previous decade including Koffee’s "West Indies," the title track on Jah9’s Note to Self featuring Chronixx, and Jesse Royal’s "Rich Forever", featuring Vybz Kartel. He also produced five of the 10 tracks on Protoje’s GRAMMY-nominated album Third Time’s The Charm.

Iotosh’s parents (Canadian music TV journalist Michele Geister and Jamaican singer/songwriter/producer Ragnam Poyser) came from different musical worlds, so he heard a multiplicity of genres growing up, including hip-hop, rock, funk, soul, reggae and R&B. Iotosh wanted to replicate all of those sounds when he started making music, which led to his genre blurring approach.

As an artist, his 2023 breakout single the meditative "Fill My Cup" (featuring Protoje on the remix) was followed this year by "Bad News," which explores grief that follows losing a loved one, both on one-drop reggae rhythms. He describes his debut eight-track EP, due in September, as "a mix of traditional reggae and elements of contemporary music, pop, hip-hop and R&B."

"In my productions, I try to have some identifiable Jamaican aspects, usually the bassline, which I play live," Iotosh tells GRAMMY.com. "Reggae is based on a universal message, it’s peace and love but contextually it comes from a place of enlightening people about forces of oppression. If that message is in the music, it’s still reggae, no matter what it sounds like."

Iotosh will make his New York City debut on July 7 at Federation Sound’s 25th Anniversary show, Coney Island Amphitheater.

Mortimer

Producer Winta James first heard Mortimer while working on sing-jay Protoje’s acclaimed 2015 album Ancient Future, and decided he was the right singer to provide the evocative hook on the opening track, "Protection." About a year after they recorded the song, Mortimer became the first artist Winta signed to his company Overstand Entertainment.

In 2019 Mortimer (born Mortimer McPherson) released his impressive EP, Fight the Fight; single "Lightning," was especially noteworthy for its roots-meets-lovers rock sound anchored in a heavy bass and delicately embellished with a steel guitar. Mortimer’s sublime high register vocals express a refreshingly vulnerable perspective: "Girl, my love grows stronger each day, baby please don't hurt me just because you know I'll forgive."

"The songs that get me the most are coming from a place deep within," Mortimer told me in a January 2020 interview. "I started out writing what I thought was expected of me as a Rasta, militant, social commentaries, but it was missing something. Before I am a Rastaman, I am a human being, so I dig deep, expressing my feelings simply, truthfully."

Mortimer’s debut album is due in September and his latest single, "Not A Day Goes By," addresses his struggles with depression: "I’ve given up 1000 times, I’ve even tried to take my own life," he sings in a haunting tone. Mental health struggles remain a taboo topic in reggae and popular music overall; Mortimer’s raw, confessional lyrics demonstrate his courageousness as an artist, and that bravery will hopefully inspire others going through similar struggles to speak out and get the help they need.

Hector "Roots" Lewis

Earlier this year, Hector "Roots" Lewis made his acting debut in the biopic Bob Marley: One Love, earning enthusiastic reviews for his portrayal of the late Carlton "Carly" Barrett, the longstanding, influential drummer with Bob Marley and The Wailers. Formerly the percussionist and backing vocalist with Chronixx’s band Zinc Fence Redemption, Hector is blazing his own trail as a vocalist, songwriter and musician.

The son of the late Jamaican lover’s rock and gospel singer Barbara Jones, Hector’s profound love for music began as a child. In 2021, Chronixx launched his Soul Circle Music label with Hector’s single "Ups and Downs," an energetic funky romp that’s a testament to music’s healing powers. The song’s lyric "never disrespect cuz mama set a foundation" directly references Hector’s mother as the primary motivating force for his musical pursuits.

In 2022 Hector toured the U.S. as the lead singer with California reggae band Tribal Seeds (when lead singer Steven Jacobo took a hiatus) taking his dynamic instrumental and vocal abilities to a wider audience. The same year, Hector released his five-track debut EP, D’Rootsman, which includes regal, soulful reggae ("King Said"), 1990s dancehall flavor ("Nuh Betta Than Yard") and R&B accented jams "Good Connection."

Co-produced with Johnny Cosmic, Hector’s latest single "Possibility" boasts an irresistible bass heavy reggae groove. On his Instagram page, Hector dedicates "Possibility" to people who are facing the terrors of "warfare, colonialism, depression and oppression," urging them to "believe in the "Possibility" that they can be free from that suffering."

Read more: 7 Things We Learned Watching 'Bob Marley: One Love'

Hempress Sativa

The daughter of Albert "Ilawi Malawi" Johnson, musician and legendary selector with Jah Love sound system, Hempress Sativa was raised in a Rastafarian household where music played an essential role in their lives. Performing since her early teens, she developed an impressive lyrical prowess and an exceptional vocal flow, effortlessly switching between singing and deejaying.

Consistently bringing a positive Rasta woman vibration to each track she touches, Hempress Sativa’s most recent album Chakra is a sophisticated mix of reggae rhythms, Afrobeats ("Take Me Home," featuring Kelissa), neo-soul ("The Best") and cavernous echo and reverb dub effects ("Sound the Trumpet"), a call to action for spiritual warriors. On "Top Rank Queens" Hempress Sativa trades verses with veterans Sister Nancy and Sister Carol, each celebrating their deeply held values and formidable mic skills as Rastafari female deejays.

Hempress Sativa is featured in the documentary Bam Bam The Sister Nancy Story, (which premiered at the Tribeca Festival on June 7) recounting the legendary toaster’s influence on her own artistry. Speaking specifically about Sister Carol, Hempress tells GRAMMY.com, "She is my mentor and to see her, as a Rastafari woman from back in the 1970s, maintain her standards and principles, gives me the confidence moving forward that I, too, can find a space within this industry where I can wholeheartedly be myself."

Learn more: The Women Essential To Reggae And Dancehall

Tarrus Riley

One of the most popular reggae songs of the 2000s was Tarrus Riley’s dulcet lover’s rock tribute to women "She’s Royal." Released in 2006 and included on his acclaimed album Parables, "She’s Royal" catapulted Tarrus to reggae stardom; the song’s video has surpassed 114 million YouTube views.

Tarrus has maintained a steady output of hit singles, while his live performances with the Blak Soil Band, led by saxophonist Dean Fraser, have established a gold standard for live reggae in this generation. Tarrus’s expressive, dynamic tenor is adaptable to numerous styles, from the stunning soft rocker "Jah Will", to the thunderous percussion driven celebration of African identity, "Shaka Zulu Pickney" and the EDM power ballad "Powerful," a U.S. certified gold single produced by Major Lazer, featuring Ellie Goulding.

His 2014 album Love Situation offered a gorgeous tribute to Jamaica’s rocksteady era (during which time his father, the late Jimmy Riley, started out as a singer in the harmony group the Sensations). Tarrus’s most recent album 2020’s Healing, includes meditative reggae ("Family Tree"), trap dancehall with Teejay referencing racial and political sparring on "Babylon Warfare," and the pop dancehall flavored hit "Lighter" featuring Shenseea (the song’s video has surpassed 102 million views).

Healing’s title track ponders what the new normal will be like, "without a simple hug, so tight and warm and snug/what will this new life be like, without a simple kiss, Jah knows I'd hate to miss."

Recorded and released at the height of the pandemic, Healing is deserving much greater recognition for its luminous production (by Tarrus, Dean Fraser and Shane Brown) brilliant musicianship, nuanced songwriting and forthright expression of the myriad, conflicting emotions many underwent during the lockdowns.

Samory I

Samory I is among the most compelling Jamaican voices of this generation, whose mesmeric tone is both a guttural cry and a clarion call to collective mobilization. Born Samory Tour Frazer (after Samory Touré, who resisted French colonial rule in 19th century west Africa), Samory I released his critically acclaimed debut album, Black Gold, in 2017.

His latest release Strength is produced by Winta James, and was the only reggae title included on Rolling Stone’s Best 100 albums of 2023. The modern roots reggae masterpiece features the affirming "Crown," on which Samory commands, "I stand my ground, I will not crumble/I keep my crown here in this jungle." Mortimer is featured on "History of Violence," which details the generational trauma that plagues ghetto residents over a classic soul-reggae riddim. "Blood in the Streets" is a blistering roots reggae anthem, an anguished exploration of the conditions that have led to the violence: "Shame to say the system that should be protecting Is still the reason we suffer/The perpetrators blame the victims, do they even listen? Can they hear us from the gutter?"

Despite the societal and personal suffering that’s conveyed ("My Son" bemoans the death of Samory’s firstborn), Samory I offers "Jah Love" urging the wronged and the wrongdoers to ‘Show no hate, hold no grudge, seek Jah love," It’s an inspirational conclusion to Strength, rooted in Rastafari’s deeply meshed mysticism and militancy.

Romain Virgo

There’s a scene in the video for Romain Virgo’s 2024 hit "Been there Before" where he sits alone in an empty room cradling a gold object with three shooting stars; those familiar Romain’s career beginnings will recognize it as the trophy the then 17-year-old won in the Jamaica’s talent contest Digicel Rising Stars, in 2007. "Been There Before" is a compelling sketch of Romain’s life’s struggles, yearning for something better, as set to a throbbing bassline: "To be someone was my heart’s desire/so me never stop send up prayer," he sings in a melancholy, quavering tone.

Growing up poor in St. Ann, Jamaica, the trophy represents the contest victory that changed Romain’s life. One of the Rising Star prizes was a recording contract with Greensleeves/VP Records. On March 1, Romain released his fourth album for VP The Gentleman, one of 2024’s finest reggae releases, evidencing Romain’s increasing sophistication as a writer and nuanced vocalist.

Throughout his career Romain has vacillated between romantic lover’s rock stylings ("Stars Across The Sky"), reggae covers of pop hits (Sam Smith’s "Stay With Me") that are so good, you’ll likely forget the originals, and organic, tightly knitted collabs including the aforementioned "Been There Before" featuring Masicka, all of which has created Romain’s large, loyal fan base and a hectic international performance schedule.

Yet, Romain’s greatest success might be maintaining the wholesome, humble personality that captivated Jamaican audiences when he won Rising Stars 17 years ago. "People have seen me grow in front of their eyes," Romain tells GRAMMY.com. "I enjoy singing positive music, knowing my songs won’t negatively impact kids. Being a husband and father now comes with much more responsibility in holding on to those values, it feels like a transition from a gentle boy into a gentleman."

Remembering Coxsone Dodd: 10 Essential Productions From The Architect Of Jamaican Music

PRIDE & Black Music Month: Celebrating LGBTQIA+ & Black Voices

Listen To GRAMMY.com's 2024 Pride Month Playlist Of Rising LGBTQIA+ Artists

9 New Pride Anthems For 2024: Sabrina Carpenter's "Espresso," Chappell Roan's "Casual" & More

What's The Future For Black Artists In Country Music? Breland, Reyna Roberts & More Sound Off

Why Beyoncé Is One Of The Most Influential Women In Music History | Run The World

9 Ways To Support Black Musicians & Creators Year-Round

How Beyoncé Is Honoring Black Music History With 'Cowboy Carter,' "Texas Hold Em," 'Renaissance' & More

The Evolution Of The Queer Anthem: From Judy Garland To Lady Gaga & Lil Nas X

15 LGBTQIA+ Artists Performing At 2024 Summer Festivals

50 Artists Who Changed Rap: Jay-Z, The Notorious B.I.G., Dr. Dre, Nicki Minaj, Kendrick Lamar, Eminem & More

Fight The Power: 11 Powerful Protest Songs Advocating For Racial Justice

How Rihanna Uses Her Superstardom To Champion Diversity | Black Sounds Beautiful

How Beyoncé Has Empowered The Black Community Across Her Music And Art | Black Sounds Beautiful

5 Women Essential To Rap: Cardi B, Lil' Kim, MC Lyte, Sylvia Robinson & Tierra Whack

Celebrate 40 Years Of Def Jam With 15 Albums That Show Its Influence & Legacy

Watch Frank Ocean Win Best Urban Contemporary Album At The 2013 GRAMMYs | GRAMMY Rewind

A Brief History Of Black Country Music: 11 Important Tracks From DeFord Bailey, Kane Brown & More

10 Women In African Hip-Hop You Should Know: SGaWD, Nadai Nakai, Sho Madjozi & More

10 Artists Shaping Contemporary Reggae: Samory I, Lila Iké, Iotosh & Others

The Rise Of The Queer Pop Star In The 2010s

How Sam Smith's 'In The Lonely Hour' Became An LGBTQIA+ Trailblazer

How Queer Country Artists Are Creating Space For Inclusive Stories In The Genre

How Jay-Z Became The Blueprint For Hip-Hop Success | Black Sounds Beautiful

How Kendrick Lamar Became A Rap Icon | Black Sounds Beautiful

Dyana Williams On Why Black Music Month Is Not Just A Celebration, But A Call For Respect

6 LGBTQIA+ Latinx Artists You Need To Know: María Becerra, Blue Rojo & More

7 LGBTQ+ Connections In The Beatles' Story

Breaking Down Normani's Journey To 'Dopamine': How Her Debut Album Showcases Resilience & Star Power

10 Alté Artists To Know: Odunsi (The Engine), TeeZee, Lady Donli & More

Celebrating Black Fashion At The GRAMMYs Throughout The Decades | Black Music Month

FLETCHER Is "F—ing Unhinged" & Proud Of It On 'In Search Of The Antidote'

For Laura Jane Grace, Record Cycles Can Be A 'Hole In My Head' — And She's OK With That

15 Essential Afrorock Songs: From The Funkees To Mdou Moctar

50 Years In, "The Wiz" Remains An Inspiration: How A New Recording Repaves The Yellow Brick Road

Why Macklemore & Ryan Lewis' "Same Love" Was One Of The 2010s' Most Important LGBTQ+ Anthems — And How It's Still Impactful 10 Years On

Songbook: The Complete Guide To The Albums, Visuals & Performances That Made Beyoncé A Cultural Force

Why Cardi B Is A Beacon Of Black Excellence | Black Sounds Beautiful

Queer Christian Artists Keep The Faith: How LGBTQ+ Musicians Are Redefining Praise Music

9 Revolutionary Rap Albums To Know: From Kendrick Lamar, Black Star, EarthGang & More

9 "RuPaul's Drag Race" Queens With Musical Second Acts: From Shea Couleé To Trixie Mattel & Willam

5 Black Artists Rewriting Country Music: Mickey Guyton, Kane Brown, Jimmie Allen, Brittney Spencer & Willie Jones

How 1994 Changed The Game For Hip-Hop

How Whitney Houston’s Groundbreaking Legacy Has Endured | Black Sounds Beautiful

LGBTQIA+-Owned Venues To Support Now

Celebrate The Genius Of Prince | Black Sounds Beautiful

Explore The Colorful, Inclusive World Of Sylvester's 'Step II' | For The Record

Black-Owned Music Venues To Support Now

5 Artists Fighting For Social Justice Today: Megan Thee Stallion, Noname, H.E.R., Jay-Z & Alicia Keys

Artists Who Define Afrofuturism In Music: Sun Ra, Flying Lotus, Janelle Monae, Shabaka Hutchings & More

5 Trans & Nonbinary Artists Reshaping Electronic Music: RUI HO, Kìzis, Octo Octa, Tygapaw & Ariel Zetina

From 'Shaft' To 'Waiting To Exhale': 5 Essential Black Film Soundtracks & Their Impact

5 Emerging Artists Pushing Electronic Music Forward: Moore Kismet, TSHA, Doechii & Others

5 Artists Essential to Contemporary Soca: Machel Montano, Patrice Roberts, Voice, Skinny Fabulous, Kes The Band

How Quincy Jones' Record-Setting, Multi-Faceted Career Shaped Black Music On A Global Scale | Black Sounds Beautiful

5 Black Composers Who Transformed Classical Music

Brooke Eden On Advancing LGBTQ+ Visibility In Country Music & Why She's "Got No Choice" But To Be Herself

Let Me Play The Answers: 8 Jazz Artists Honoring Black Geniuses

Women And Gender-Expansive Jazz Musicians Face Constant Indignities. This Mentorship Organization Is Tackling The Problem From All Angles.

Histories: From The Yard To The GRAMMYs, How HBCUs Have Impacted Music

How HBCU Marching Band Aristocrat Of Bands Made History At The 2023 GRAMMYs

Photo: David Corio/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

list

Remembering Coxsone Dodd: 10 Essential Productions From The Architect Of Jamaican Music

Regarded as Jamaica’s Motown, Coxsone Dodd's Studio One helped launch the careers of legends such as Burning Spear, Toots and the Maytals, and the Wailers. In honor of the 20th anniversary of Dodd’s passing, learn about 10 of his greatest productions.

On April 30, 2004, producer Clement Seymour "Sir Coxsone" Dodd — an architect in the construction of Jamaica’s recording industry — was honored at a festive street renaming ceremony on Brentford Road in Kingston, Jamaica. The bustling, commercial thoroughfare at the geographical center of Kingston was rechristened Studio One Blvd. in recognition of Coxsone’s recording studio and record label.

Dodd is said to have acquired a former nightclub at 13 Brentford Road in 1962; his father, a construction worker, helped him transform the building into the landmark studio. In 1963 Dodd installed a one-track board and began recording and issuing records on the Studio One label.

Dodd’s Studio One was Jamaica’s first Black-owned recording facility and is regarded as Jamaica’s Motown because of its consistent output of hit records. Studio One releases helped launch the careers of numerous ska, rocksteady and reggae legends including Bob Andy, Dennis Brown, Burning Spear, Alton Ellis, the Gladiators, the Skatalites, Toots and the Maytals, Marcia Griffiths, Sugar Minott, Delroy Wilson and most notably, the Wailers.

At the street renaming ceremony, a jazz band played, speeches were given in tribute to Dodd’s immeasurable contributions to Jamaican music and many heartfelt memories from the studio’s heyday were shared. In the culmination of the late afternoon program, Dodd, his wife Norma, and Kingston’s then mayor Desmond McKenzie unveiled the first sign bearing the name Studio One Blvd. Four days later, on April 4, 2002, Coxsone Dodd suffered a fatal heart attack at Studio One. His productions, however, live on as benchmarks within the island’s voluminous and influential music canon.

Born Clement Seymour Dodd on Jan. 26, 1932, he was given the nickname Sir Coxsone after the star British cricketer whose batting skills Clement was said to match. As a teenager, Dodd developed a fondness for jazz and bebop that he heard beamed into Jamaica from stations in Miami and Nashville and the big band dances he attended in Kingston. Dodd launched Sir Coxsone’s Downbeat sound system around 1952 with the impressive collection of R&B and jazz discs he amassed while living in the U.S., working as a seasonal farm laborer.

Many sound system proprietors traveled to the U.S. to purchase R&B records — the preferred music among their dance patrons and key to a sound system’s following and trumping an opponent in a sound clash. With the birth of rock and roll in the mid-1950s, suitable R&B records became scarce. Jamaica’s ever-resourceful sound men ventured into Kingston studios to produce R&B shuffle recordings for sound system play.

Recognizing there was a wider market for this music, Dodd pressed up a few hundred copies of two sound system favorites for general release, the instrumental "Shuffling Jug" by bassist Cluett Johnson and his Blues Blasters and singer/pianist Theophilus Beckford’s "Easy Snapping," both issued on Dodd’s first label, Worldisc. (Some historians recognize "Easy Snapping" as a bridge between R&B shuffle and the island’s Indigenous ska beat; others cite it as the first ska record.) When those discs sold out within a few days, other soundmen followed Dodd’s lead and Jamaica’s commercial recording industry began to flourish.

"Before then, the only stuff released commercially were mento records that were recorded here, but our sound really hit so we kept on recording. When I heard 'Easy Snapping,' I said 'Oh my gosh!'" Coxsone recalled in a 2002 interview for Air Jamaica's Skywritings at Kiingston’s Studio One. "I thank God for that moment."

Dodd was the first producer to enlist a house band, pay them a weekly salary rather than per record. Together, they had an impressive run of hits in the ska era in the early ‘60s; during the rocksteady period later in the decade, Dodd ceded top ranking status to long standing sound system rival (but close family friend) turned producer Duke Reid. (Still, Studio One released the most enduring instrumentals or rhythm tracks, also known as riddims, of the period.) As rocksteady morphed into reggae circa 1968, Dodd triumphed again with consistent releases of exceptional quality.

In 1979 armed robbers targeted the Brentford Rd premises several times. Dodd left Jamaica and established Coxsone’s Music City record store/recording studio in Brooklyn, dividing his time between New York and Kingston. Reissues of Dodd’s music via Cambridge, MA based Heartbeat Records, beginning in the mid 1980s, followed by London’s Soul Jazz label in the 2000s, and most recently Yep Roc Records in Hillsborough, NC, have helped introduce Studio One’s masterful work to new generations of fans.

"The best time I’ve ever had was when I acquired my studio at 13 Brentford Rd. because you can do as many takes until we figured that was it," Coxsone reflected in the 2002 interview. "God gave me a gift of having the musicians inside the studio to put the songs together. In the studio, I always thought about the fans, making the music more pleasing for listening or dancing. What really helped me was having the sound system, you play a record, and you weren’t guessing what you were doing, you saw what you were doing."

To commemorate the 20th anniversary of Coxsone Dodd’s passing, read on for a list of 10 of his greatest productions.

The Maytals - "Six and Seven Books of Moses" (1963)

In 1961 at the dawn of Jamaica’s ska era, Toots Hibbert met singers Nathaniel "Jerry" Matthias and Henry "Raleigh" Gordon and they formed the Maytals. The trio released several hits for Dodd including the rousing, "Six and Seven Books of Moses," a gospel-drenched ska track that’s essentially a shout out of a few Old Testament chapters.

Moses is credited with writing five chapters, as the lyrics state, "Genesis and Exodus, Leviticus and Numbers Deuteronomy," but "the Six and Seven books" are in question. Many Biblical scholars say Moses wasn’t the scribe, believing those chapters, including phony spells and incantations to keep evil spirits away, were penned in the 18th or 19th century.

Nevertheless, there’s a real magic formula in The Maytals’ "Six and Seven Books of Moses": Toots’ electrifying preacher at the pulpit delivery melds with elements of vintage soul, gritty R&B, and classic country; Jerry and Raleigh provide exuberant backing vocals and seminal ska outfit and Studio One’s first house band, the Skatalities deliver an irresistible, jaunty ska rhythm with a sophisticated jazz underpinning.

The Wailers - "Simmer Down" (1964)

A flashback scene in the biopic Bob Marley: One Love depicts the Wailers (then a teenaged outfit called the Juveniles) approaching Dodd for a recording opportunity; Dodd inexplicably points a gun at them as they recoil in terror. Yet, there isn’t any mention of such an inappropriate and unprovoked action from the producer in the various books, documentaries, interviews and other accounts of the Wailers’ audition for Dodd.

The Wailers’ first recording session with Dodd in July 1964, however, yielded the group’s first hit single "Simmer Down." At that time, the Wailers lineup consisted of founding members Bob Marley, Bunny Livingston (later Wailer) and Peter Tosh alongside singers Junior Braithwaite and (the sole surviving member) Beverley Kelso. When Junior left for the U.S., Dodd appointed Marley as the group’s lead singer.

The energetic "Simmer Down" cautions the impetuous rude boys to refrain from their hooligan exploits. The Skatalites’ spirited horn led intro, thumping jazz infused bass and fluttering sax solo, enhances Marley’s youthful lead and the backing vocalists’ effervescence. The Wailers would spend two years at Studio One and record over 100 songs there, including the first recording of "One Love" in 1965; by early 1966, they would have five songs produced by Dodd in the Jamaica Top 10.

Alton Ellis -"I’m Still In Love" (1967)

Jamaica’s brief rocksteady lasted about two years between 1966-1968, but was an exceptionally rich and influential musical era. The rocksteady tempo maintained the accentuated offbeat of its ska predecessor, but its slower pace allowed vocal and musical arrangements, affixed in heavier, more melodic basslines.

Alton Ellis is considered the godfather of rocksteady because he had numerous hits during the era and released "Rock Steady," the first single to utilize the term for producer Duke Reid. Ellis initially worked with Dodd in the late 1950s then returned to him in 1967. The evergreen "I’m Still in Love" was penned by Alton as a plea to his wife as their marriage dissolved: "You don’t know how to love me, or even how to kiss me/I don’t know why." Supporting Alton’s elegant, soulful rendering of heartbreak, Studio One house band the Soul Vendors, led by keyboardist Jackie Mittoo, provide an engaging horn-drenched rhythm, epitomizing what was so special about this short-lived time in Jamaican music.

"I’m Still In Love" has been covered by various artists including Sean Paul and Sasha, whose rendition reached No. 14 on the Billboard Hot 100 in 2004. Beyoncé utilized Jamaican singer Marcia’s Aitken’s 1978 version of the tune in a TV ad announcing her 2018 On The Run II tour with Jay-Z. In February 2024, Jennifer Lopez sampled "I’m Still in Love" for her single "Can’t Get Enough."

Bob Andy - "I’ve Got to Go Back Home" (1967)

The late Keith Anderson, known professionally as Bob Andy, arrived at Studio One in 1967. He quickly became a hit-making vocalist, and an invaluable writer for other artists on the label. He penned several hits for Marcia Griffiths including "Feel Like Jumping," "Melody Life" and "Always Together," the latter their first of many hit recordings as a duo.

A founding member of the vocal trio the Paragons, "I’ve Got to go Back Home" was Andy’s first solo hit and it features sublime backing vocals by the Wailers (Bunny, Peter and Constantine "Vision" Walker; Bob Marley was living in the USA at the time.) Set to a sprightly rock steady beat featuring Bobby Ellis (trumpet), Roland Alphonso (saxophone) and Carlton Samuels’ (saxophone) harmonizing horns, Andy’s lyrics poignantly depict the challenges endured by Jamaica’s poor ("I can’t get no clothes to wear, can’t get no food to eat, I can’t get a job to get bread") while expressing a longing to return to Africa, a central theme within 1970s Rasta roots reggae.

The depth of Andy’s lyrics expanded the considerations of Jamaican songwriters and one of his primary influences was Bob Dylan. "When I heard Bob Dylan, it occurred to me for the first time that you don’t have to write songs about heart and soul," Andy told Billboard in 2018. "Bob Dylan’s music introduced me to the world of social commentary and that set me on my way as a writer."

Dawn Penn - "You Don’t Love Me" (1967)

Dawn Penn’s plaintive, almost trancelike vocals and the lilting rock steady arrangement by the Soul Vendors transformed Willie Cobbs’ early R&B hit "You Don’t Love Me," based on Bo Diddley’s 1955 gritty blues lament "She’s Fine, She’s Mine," into a Jamaican classic. The song’s shimmering guitar intro gives way to the forceful drum and bass with Mittoo’s keyboards providing an understated yet essential flourish.

In 1992 Jamaica’s Steely and Clevie remade the song, featuring Penn, for their album Steely and Clevie Play Studio One Vintage. The dynamic musician/production duo brought their mastery (and 1990s technological innovations) to several Studio One classics with the original singers. Heartbeat released "You Don’t Love Me" as a single and it reached No. 58 on the Billboard Hot 100.

Several artists have reworked Penn’s rendition or sampled the Soul Vendors’ arrangement including rapper Eve on a collaboration with Stephen and Damian Marley. Rihanna recruited Vybz Kartel for an interpretation included on her 2005 debut album Music of the Sun, while Beyoncé performed the song on her I Am world tour in 2014 and recorded it in 2019 for her Homecoming: The Live Album. In 2013, Los Angeles-based Latin soul group the Boogaloo Assassins brought a salsa flavor to Penn's tune, creating a sought-after DJ single.

The Heptones - "Equal Rights" (1968)

"Every man has an equal right to live and be free/no matter what color, class or race he may be," sings an impassioned Leroy Sibbles on "Equal Rights," the Heptones’ stirring plea for justice.

Harmony vocalist Earl Morgan formed the group with singer Barry Llewellyn in the early '60s and Sibbles joined them a few years later. The swinging bass line, played by Sibbles, anchors a stunning rock steady rhythm track awash in cascading horns, and blistering percussion patterns akin to the akete or buru drums heard at Rastafari Nyabinghi sessions.

Besides leading the Heptones’ numerous hit singles during their five-year stint at Studio One, Sibbles was a talent scout, backing vocalist, resident bassist and the primary arranger, alongside Jackie Mittoo. Sibbles’ progressive basslines are featured on numerous Studio One nuggets (many appearing on this list) and have been sampled or remade countless times over the decades on Jamaican and international hits.

In a December 2023 interview Sibbles echoed a complaint expressed by many who worked at Studio One: Dodd didn’t fairly compensate his artists and the (uncredited) musicians produced the songs while Dodd tended to business matters. "When we started out, we didn’t know about the business, and what happened, happened. But as you learn as you go along," he said. "I have registered what I could; I am living comfortably so I am grateful."

The Cables - "Baby Why" (1968)

Formed in 1962 by lead singer Keble Drummond and backing vocalists Vincent Stoddart and Elbert Stewart, the Cables — while not as well-known as the Wailers, the Maytals or the Heptones — recorded a few evergreen hits at Studio One, including the enchanting "Baby Why."

Keble’s aching vocals lead this breakup tale as he warns the woman who left that she’ll soon regret it. The simple story line is delivered via a gorgeous melody that’s further embellished by Vincent and Elbert’s superb harmonizing, repeatedly cooing to hypnotic effect "why, why oh, why?"

Coxsone is said to have kept the song for exclusive sound system play for several months; when he finally released it commercially, "Baby Why" stayed at No. 1 for four weeks.

"Baby Why" is notable for another reason: although the Maytals’ "Do The Reggay" marks the initial use of the word reggae in a song, "Baby Why" is among a handful of songs cited as the first recorded with a reggae rhythm (reggae basslines are fuller and reggae’s tempo is a bit slower than its rocksteady forerunner.) Other contenders for that historic designation include Lee "Scratch Perry’s "People Funny Boy," the Beltones’ "No More Heartache," and Larry Marshall and Alvin Leslie’s delightful "Nanny Goat."

Burning Spear - "Door Peeper" (1969)

Hailing from the parish of St. Ann, Jamaica, Burning Spear was referred to Studio One by another St. Ann native, Bob Marley. Spear’s first single for Studio One "Door Peeper" (also known as "Door Peep Shall Not Enter") recorded in 1969, sounded unlike any music released by Dodd and was critical in shaping the Rastafarian roots reggae movement of the next decade.

The song’s biblically laced lyrics caution informers who attempt to interfere with Rastafarians, considered societal outcasts at the time in Jamaica, while Spear’s intonation to "chant down Babylon" creates a haunting mystical effect, supported by Rupert Willington’s evocative, deep vocal pitch, a throbbing bass, mesmeric percussion and magnificent horn blasts.

As Spear told GRAMMY.com in September 2023, "When Mr. Dodd first heard 'Door Peep' he was astonished; for a man who’d been in the music business for so long, he never heard anything like that." Dodd’s openness to recording Rasta music, and allowing ganja smoking on the premises (but not in the studio) when his competitors didn’t put him in the forefront at the threshold of the roots reggae era.

"Door Peeper" was included on Burning Spear’s debut album, Studio One Presents Burning Spear, released in 1973 and remains a popular selection in the legendary artist’s live sets.

Joseph Hill - "Behold The Land" (1972)

In the October 1946 address Behold The Land by W. E. B. DuBois at the closing session of the Southern Youth Legislature in Columbia, South Carolina, the then 78-year-old celebrated author and activist urges Black youth to fight for racial equality and the civil rights denied them in Southern states. The late Joseph Hill’s 1972 song of the same name, possibly influenced by Dubois’ words, is a powerful reggae missive exploring the atrocities of the transatlantic slave trade from which descended the discriminations DuBois described.

Hill was just 23 when he wrote/recorded "Behold The Land," his debut single as a vocalist. Hill’s haunting timbre summons the harrowing experience with the wisdom and emotional rendering of an ancestor: "For we were brought here in captivity, bound in links and chains and we worked as slaves and they lashed us hard." Hill then gives praise and asks for repatriation to the African motherland, "let us behold the land where we belong."

The Soul Defenders — a self contained entity but also a Studio One house band with whom Hill made his initial recordings as a percussionist — provide a persistent, bass heavy rhythm that suitably frames Hill’s lyrical gravitas, as do the melancholy hi-pitched harmonies.

In 1976 Hill formed the reggae trio Culture and the next year they catapulted to international fame with their apocalyptic single "Two Sevens Clash," which prompted Dodd to finally release "Behold The Land." Culture would re-record "Behold The Land" over the years including for their 1978 album Africa Stand Alone and the song received a digital remastering in 2001.

Sugar Minott - "Oh Mr. DC" (1978)

In the mid-1970s singer Lincoln "Sugar" Minott began writing lyrics to classic 1960s Studio One riddims, an approach that launched his hitmaking solo career and further popularized the practice of riddim recycling — which is still a standard approach in dancehall production. Sugar, formerly with the vocal trio The African Brothers, penned one of his earliest solo hits "Oh, Mr. DC" to the lively beat of the Tennors’ 1967 single "Pressure and Slide" (itself a riddim originally heard, at a faster pace, underpinning Prince Buster’s 1966 "Shaking Up Orange St.")

"Oh, Mr. DC" is an authentic tale of a ganja dealer returning from the country with his bag of collie (marijuana); the DC (district constable/policeman) says he’s going to arrest him and threatens to shoot if he attempts to run away. Sugar explains to the officer that selling herb is how he supports his family: "The children crying for hunger/ I man a suffer, so you’ve got to see/it’s just collie that feed me." To underscore his urgent plea, Sugar wails in an unforgettable melody, "Oh, oh DC, don’t take my collie."

The irresistibly bubbling bassline of the riddim nearly obscures the song’s poignant depiction of Jamaica’s harsh economic realities and the potential risk of imprisonment, or worse, that the island’s ganja sellers faced at the time. Sugar’s revival of a Studio One riddim and reutilization of 10 Studio One riddims for each track of his 1977 album Live Loving brought renewed interest to the treasures that could be extracted from Mr. Dodd’s vaults.

Special thanks to Coxsone Dodd’s niece Maxine Stowe, former A&R at Sony/Columbia and Island Records, who started her career at Coxsone’s Music City, Brooklyn.

How 'The Harder They Come' Brought Reggae To The World: A Song By Song Soundtrack Breakdown

Photo: Jeff Kravitz/FilmMagic

video

GRAMMY Rewind: Kendrick Lamar Honors Hip-Hop's Greats While Accepting Best Rap Album GRAMMY For 'To Pimp a Butterfly' In 2016

Upon winning the GRAMMY for Best Rap Album for 'To Pimp a Butterfly,' Kendrick Lamar thanked those that helped him get to the stage, and the artists that blazed the trail for him.

Updated Friday Oct. 13, 2023 to include info about Kendrick Lamar's most recent GRAMMY wins, as of the 2023 GRAMMYs.

A GRAMMY veteran these days, Kendrick Lamar has won 17 GRAMMYs and has received 47 GRAMMY nominations overall. A sizable chunk of his trophies came from the 58th annual GRAMMY Awards in 2016, when he walked away with five — including his first-ever win in the Best Rap Album category.

This installment of GRAMMY Rewind turns back the clock to 2016, revisiting Lamar's acceptance speech upon winning Best Rap Album for To Pimp A Butterfly. Though Lamar was alone on stage, he made it clear that he wouldn't be at the top of his game without the help of a broad support system.

"First off, all glory to God, that's for sure," he said, kicking off a speech that went on to thank his parents, who he described as his "those who gave me the responsibility of knowing, of accepting the good with the bad."

Looking for more GRAMMYs news? The 2024 GRAMMY nominations are here!

He also extended his love and gratitude to his fiancée, Whitney Alford, and shouted out his Top Dawg Entertainment labelmates. Lamar specifically praised Top Dawg's CEO, Anthony Tiffith, for finding and developing raw talent that might not otherwise get the chance to pursue their musical dreams.

"We'd never forget that: Taking these kids out of the projects, out of Compton, and putting them right here on this stage, to be the best that they can be," Lamar — a Compton native himself — continued, leading into an impassioned conclusion spotlighting some of the cornerstone rap albums that came before To Pimp a Butterfly.

"Hip-hop. Ice Cube. This is for hip-hop," he said. "This is for Snoop Dogg, Doggystyle. This is for Illmatic, this is for Nas. We will live forever. Believe that."

To Pimp a Butterfly singles "Alright" and "These Walls" earned Lamar three more GRAMMYs that night, the former winning Best Rap Performance and Best Rap Song and the latter taking Best Rap/Sung Collaboration (the song features Bilal, Anna Wise and Thundercat). He also won Best Music Video for the remix of Taylor Swift's "Bad Blood."

Lamar has since won Best Rap Album two more times, taking home the golden gramophone in 2018 for his blockbuster LP DAMN., and in 2023 for his bold fifth album, Mr. Morale & the Big Steppers.

Watch Lamar's full acceptance speech above, and check back at GRAMMY.com every Friday for more GRAMMY Rewind episodes.

10 Essential Facts To Know About GRAMMY-Winning Rapper J. Cole

Photo: Rachel Kupfer

list

A Guide To Modern Funk For The Dance Floor: L'Imperatrice, Shiro Schwarz, Franc Moody, Say She She & Moniquea

James Brown changed the sound of popular music when he found the power of the one and unleashed the funk with "Papa's Got a Brand New Bag." Today, funk lives on in many forms, including these exciting bands from across the world.

It's rare that a genre can be traced back to a single artist or group, but for funk, that was James Brown. The Godfather of Soul coined the phrase and style of playing known as "on the one," where the first downbeat is emphasized, instead of the typical second and fourth beats in pop, soul and other styles. As David Cheal eloquently explains, playing on the one "left space for phrases and riffs, often syncopated around the beat, creating an intricate, interlocking grid which could go on and on." You know a funky bassline when you hear it; its fat chords beg your body to get up and groove.

Brown's 1965 classic, "Papa's Got a Brand New Bag," became one of the first funk hits, and has been endlessly sampled and covered over the years, along with his other groovy tracks. Of course, many other funk acts followed in the '60s, and the genre thrived in the '70s and '80s as the disco craze came and went, and the originators of hip-hop and house music created new music from funk and disco's strong, flexible bones built for dancing.

Legendary funk bassist Bootsy Collins learned the power of the one from playing in Brown's band, and brought it to George Clinton, who created P-funk, an expansive, Afrofuturistic, psychedelic exploration of funk with his various bands and projects, including Parliament-Funkadelic. Both Collins and Clinton remain active and funkin', and have offered their timeless grooves to collabs with younger artists, including Kali Uchis, Silk Sonic, and Omar Apollo; and Kendrick Lamar, Flying Lotus, and Thundercat, respectively.

In the 1980s, electro-funk was born when artists like Afrika Bambaataa, Man Parrish, and Egyptian Lover began making futuristic beats with the Roland TR-808 drum machine — often with robotic vocals distorted through a talk box. A key distinguishing factor of electro-funk is a de-emphasis on vocals, with more phrases than choruses and verses. The sound influenced contemporaneous hip-hop, funk and electronica, along with acts around the globe, while current acts like Chromeo, DJ Stingray, and even Egyptian Lover himself keep electro-funk alive and well.

Today, funk lives in many places, with its heavy bass and syncopated grooves finding way into many nooks and crannies of music. There's nu-disco and boogie funk, nodding back to disco bands with soaring vocals and dance floor-designed instrumentation. G-funk continues to influence Los Angeles hip-hop, with innovative artists like Dam-Funk and Channel Tres bringing the funk and G-funk, into electro territory. Funk and disco-centered '70s revival is definitely having a moment, with acts like Ghost Funk Orchestra and Parcels, while its sparkly sprinklings can be heard in pop from Dua Lipa, Doja Cat, and, in full "Soul Train" character, Silk Sonic. There are also acts making dreamy, atmospheric music with a solid dose of funk, such as Khruangbin’s global sonic collage.

There are many bands that play heavily with funk, creating lush grooves designed to get you moving. Read on for a taste of five current modern funk and nu-disco artists making band-led uptempo funk built for the dance floor. Be sure to press play on the Spotify playlist above, and check out GRAMMY.com's playlist on Apple Music, Amazon Music and Pandora.

Say She She

Aptly self-described as "discodelic soul," Brooklyn-based seven-piece Say She She make dreamy, operatic funk, led by singer-songwriters Nya Gazelle Brown, Piya Malik and Sabrina Mileo Cunningham. Their '70s girl group-inspired vocal harmonies echo, sooth and enchant as they cover poignant topics with feminist flair.

While they’ve been active in the New York scene for a few years, they’ve gained wider acclaim for the irresistible music they began releasing this year, including their debut album, Prism. Their 2022 debut single "Forget Me Not" is an ode to ground-breaking New York art collective Guerilla Girls, and "Norma" is their protest anthem in response to the news that Roe vs. Wade could be (and was) overturned. The band name is a nod to funk legend Nile Rodgers, from the "Le freak, c'est chi" exclamation in Chic's legendary tune "Le Freak."

Moniquea

Moniquea's unique voice oozes confidence, yet invites you in to dance with her to the super funky boogie rhythms. The Pasadena, California artist was raised on funk music; her mom was in a cover band that would play classics like Aretha Franklin’s "Get It Right" and Gladys Knight’s "Love Overboard." Moniquea released her first boogie funk track at 20 and, in 2011, met local producer XL Middelton — a bonafide purveyor of funk. She's been a star artist on his MoFunk Records ever since, and they've collabed on countless tracks, channeling West Coast energy with a heavy dose of G-funk, sunny lyrics and upbeat, roller disco-ready rhythms.

Her latest release is an upbeat nod to classic West Coast funk, produced by Middleton, and follows her February 2022 groovy, collab-filled album, On Repeat.

Shiro Schwarz

Shiro Schwarz is a Mexico City-based duo, consisting of Pammela Rojas and Rafael Marfil, who helped establish a modern funk scene in the richly creative Mexican metropolis. On "Electrify" — originally released in 2016 on Fat Beats Records and reissued in 2021 by MoFunk — Shiro Schwarz's vocals playfully contrast each other, floating over an insistent, upbeat bassline and an '80s throwback electro-funk rhythm with synth flourishes.

Their music manages to be both nostalgic and futuristic — and impossible to sit still to. 2021 single "Be Kind" is sweet, mellow and groovy, perfect chic lounge funk. Shiro Schwarz’s latest track, the joyfully nostalgic "Hey DJ," is a collab with funkstress Saucy Lady and U-Key.

L'Impératrice

L'Impératrice (the empress in French) are a six-piece Parisian group serving an infectiously joyful blend of French pop, nu-disco, funk and psychedelia. Flore Benguigui's vocals are light and dreamy, yet commanding of your attention, while lyrics have a feminist touch.

During their energetic live sets, L'Impératrice members Charles de Boisseguin and Hagni Gwon (keys), David Gaugué (bass), Achille Trocellier (guitar), and Tom Daveau (drums) deliver extended instrumental jam sessions to expand and connect their music. Gaugué emphasizes the thick funky bass, and Benguigui jumps around the stage while sounding like an angel. L’Impératrice’s latest album, 2021’s Tako Tsubo, is a sunny, playful French disco journey.

Franc Moody

Franc Moody's bio fittingly describes their music as "a soul funk and cosmic disco sound." The London outfit was birthed by friends Ned Franc and Jon Moody in the early 2010s, when they were living together and throwing parties in North London's warehouse scene. In 2017, the group grew to six members, including singer and multi-instrumentalist Amber-Simone.

Their music feels at home with other electro-pop bands like fellow Londoners Jungle and Aussie act Parcels. While much of it is upbeat and euphoric, Franc Moody also dips into the more chilled, dreamy realm, such as the vibey, sultry title track from their recently released Into the Ether.