Photo: Celine Pinget

Antibalas

news

Meet The First-Time GRAMMY Nominee: Antibalas Talk 'Fu Chronicles,' Kung Fu And Their Mission To Spread Afrobeat

Antibalas members Martín Perna and Duke Amayo discuss their origin story, their decades-long rise as an outlier in Brooklyn and how their first-ever GRAMMY nomination for Best Global Music Album could help introduce new listeners to Afrobeat

Even somebody who barely listens to music could presumably name three artists in each of these spheres: rock, blues and jazz. Sure, Bob Marley may remain the embodiment of reggae, but chances are you've heard of Toots and the Maytals or Lee "Scratch" Perry at least once. What about Afrobeat, a West African amalgam of soul and funk with regional styles like Yoruba and highlife?

For many, the Afrobeat conversation begins and ends with the outrageous, incendiary, brilliant multi-instrumentalist and pioneer of the form, Fela Kuti. While the Brooklyn Afrobeat ensemble Antibalas, which ranges from 11 to 19 members, undoubtedly work from the template Kuti helped create, they argue the story of Afrobeat begins—not ends—with him.

"I think that's one of the weirdest things, being in a genre of music that is so defined and predetermined by one person," Martín Perna, the multi-instrumentalist who first dreamed up Antibalas in 1998, tells GRAMMY.com. "Even reggae artists don't all get compared to Bob Marley. I don't think anybody in any other genre is in the shadow of one person like people who play this music." (For those who wish to dig deeper, Perna recommends Geraldo Pino, Orchestre Poly-Rythmo de Cotonou and the Funkees; his bandmate, Duke Amayo, name-drops Orlando Julius.)

"It's been a weird thing," Perna continues. "I would have thought after 22 years that it would have expanded a little bit more."

More than 20 years after Kuti's death in 1997, Afrobeat may soon expand radically in the public eye thanks to Antibalas. The group, who played their first gig half a year after Kuti's passing, has been nominated at the 2021 GRAMMYs Awards show in the newly renamed Best Global Music Album category for Fu Chronicles, which dropped last February on Daptone Records. Their first album to be solely written by lead singer and percussionist Amayo, its highlights, like "Lai Lai," "MTTT, Pt. 1 & 2" and "Fist of Flowers," partly derive their power from his other primary pursuit: kung fu.

A Nigerian-born multidisciplinarian who is a senior master at the Jow Ga Kung Fo School of martial arts, Amayo aims to find the nexus point between music, dance and martial arts. When he received the unexpected news that Antibalas had clinched their first-ever GRAMMY nomination after 20 years in the game, he launched into a dance of his own.

"I walked over to my girl and said, 'Check this out. Is this real?'" he recalls to GRAMMY.com with a laugh. "She Googled the GRAMMY nominations, and it was surreal. And then I did that usual thing where you shake your hips, violently doing the hip thrust back and forth. Then, I woke the whole house up screaming, as my daughter screamed with me for a minute or two."

GRAMMY.com spoke with Martín Perna and Duke Amayo about Antibalas' origin story, their decades-long rise as an outlier in Brooklyn and how their nomination could help introduce new listeners to Afrobeat.

These interviews have been edited and condensed for clarity.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//FwwpHDxl3oc' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

How would you explain the vocabulary of someone like Fela Kuti to a person who's unfamiliar?

Martín Perna: Afrobeat is like musical architecture. It's a set of ingredients and musical relationships between those ingredients. All the instruments are talking to each other. They're all in dialogue, and these dialogues create dynamic tension in the music. Some instruments create a rigid structure, and others—vocals included—have much more free reign to improvise or solo.

Duke Amayo: I would describe it as a tonal language of the common Nigerian—or African—singing truth to power from a marginalized place. That is the window from where Fela Kuti was operating. He drew from observations around him and expressed them truthfully throughout his music. He is like the Bob Marley and the James Brown of Nigeria rolled into one.

Perna: Whereas the guitar might be playing the same five-note pattern without stopping for 20 minutes, the singer or keyboardist gets to improvise. Or, when the horns aren't playing the melodies, they get solos. It's both very rigid and very free, but it's a dynamic tension between the two.

In a nutshell, describe how Antibalas came up in the Brooklyn scene.

Perna: I was 22 when I dreamed this up, and a lot of it was just trying to create a scene that I wanted to be part of. At the time, I played with Sharon Jones—rest in peace—Sharon Jones & the Dap-Kings. A bunch of the musicians were my colleagues in that band. The rest of the musicians came pretty much from the neighborhood—just people I knew who either had the chops or the interest to be in this band.

Amayo: I was living in Williamsburg, a neighborhood that embodied gentrification in record time. I was in the right place at the right time as I opened a clothing store/martial-arts dojo in my residence called the Afro-Spot. From here, I hosted many fashion shows, using Nigerian drummers to maintain an edge to my brand. This exposed me to musicians who wanted to make resistance music, if you will.

So that brought me in contact with Martín and [Daptone Records co-founder and former Antibalas guitarist] Gabe [Roth], who stopped in my store one day to hang. Eventually, they asked me to join the band. I started as a percussionist and then became the lead singer.

Perna: I wanted to make a band that was both a dance band and a protest band. Because you need so many people to make this music, it fulfilled that idea of being a band and a community. You need anywhere from 11 [musicians] on the small end; at our biggest shows, there have been 19 musicians on stage. So, already, you have a community of people.

Coming up in Brooklyn, did you have local peers in this style? Was there a scene?

Perna: No, there wasn't a scene. There were individuals—mostly West African guys a generation older than us—that had played with Fela or were part of some other African funk band in the '70s. But no, there weren't any peers at all.

Amayo: I would state that we were the scene.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//ipykSS6lyXI' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

How would you describe your vision for Fu Chronicles as opposed to past Antibalas albums?

Amayo: Fu Chronicles is a concept album written by only me. While the past albums have been written by different members employing the group dynamics of the time, my vision was to create a musical universe where African folklore and kung fu wisdom can coexist seamlessly, supporting each other in a harmonious flow.

The first song I composed [20 years ago], "MTTT," came from my intention to compose a timeless, logical song, expressing a new frontier in classical African music. I wanted to move the music forward by writing songs with two distinct-but-related bass and guitar lines and shape the grooves into a two-part form: yin and yang.

How did martial arts play into the album?

Amayo: I wanted to reimagine Afrobeat songs from a real kung fu practitioner's mindset. I'm a certified Jow Ga Kung Fu sifu, or master. I started studying kung fu in Nigeria as a young boy. The song "Fist of Flowers" describes the traditional form of Jow Ga Kung Fu that I teach. My rhythmic blocks are sometimes based on the shapes of my kung fu movements.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//k5rXpSr7x0A' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

How did you learn about your GRAMMY nomination for Best Global Music Album?

Amayo: The first person who texted me was Kyle Eustice, [who interviewed me in 2020] for High Times. I didn't react at first. I walked over to my girl and said, "Check this out. Is this real?" She Googled the GRAMMY nominations, and it was surreal.

I did that usual thing where you shake your hips, violently doing the hip thrust back and forth, and quickly calmed down. Then I woke the whole house up screaming as my daughter screamed with me for a minute or two.

Perna: On my fridge, last year, when I set my goals and intentions, one of the five things [I wrote] was to win a GRAMMY. This year has been such a disappointment in so many ways, so it's exciting that at least we got, so far, the nomination.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//Cb8I99w-wrQ' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

This nomination serves as a punctuation mark on Antibalas's 20-plus-year career. How do you see the next 20 years?

Perna: Oh, gosh. I hope it provides some wind in our sails to continue to record and tour and grow our audience. It could be either a nice end to a beautiful history of the band, or something like I said: wind in our sails.

Amayo: I see the next 20 years of Antibalas as a flower in full growth, writing music to push the genre forward while maintaining excellence in the trade. We began as a bunch of guys in Brooklyn who wanted to make a change, make some noise, and be part of the revival of activist music.

And it's still as relevant as ever, demanding for justice movements like Black Lives Matter, Indigenous peoples' plight, and a more comprehensive education system based on truth ...

Perna: … To get this recommendation and this nod from the GRAMMYs, it's like, "Hey, everybody! Pay attention to this band! They made this amazing record, and you should listen to it!" That's something that propels us out of the world of just musicians listening to us. It feels good to get a little bit of wider recognition.

Amayo: I've been praising my wife ever since [the nomination]: "This is all mostly you." Because if she hadn't put a fire in me, I wouldn't have been able to make the right moves. It takes something to light it up for you, to believe you can get there.

Thus, my song, "Fight Am Finish," with the lyrics, "Never, ever let go of your dreams." I'm going to keep running. I'm going to keep my feet moving until I cross the finish line, you know what I mean?

Travel Around The World With The Best Global Music Album Nominees | 2021 GRAMMYs

Photo: Sven de Almeida

interview

Meet KOKOKO! The DIY Electronic Group Channeling The Chaos & Resilience Of Kinshasa

The exciting live electronic act out of the Congo discusses their fiery, pulsing, sophomore album, 'BUTU,' the manic sound of Kinshasa, and using improvisation to keep their performances energized.

No one else sounds like KOKOKO! — they are a truly unique aural experience, an emphatic statement that does justice to the exclamation point in their name.

The experimental live electronic group out of Kinshasa — the active, populous capital of the Democratic Republic of Congo — is a reflection of their city. Their shouted and chanted lyrics reflect people's frustration with their government, as well as the sonic signals of industrious local vendors. Even their DIY instruments are an example of their resourcefulness: Although DRC is a resource-rich country, that wealth has been extracted by and for Western powers for centuries. Locals are left with limited resources and experience regular power outages and intense, ongoing conflict.

KOKOKO! was born after French electronic producer Xavier Thomas — who makes left-field, globally-influenced electronic music as Débruit — met talented local singer and musician Makara Bianko on a visit to Kinshasa. He was captivated by Bianko's large, nearly daily outdoor performances with his massive dance crew. The group, which also consists of locals Boms and Dido who fashion DIY instruments, incorporate much of Makara's improvisational and interdisciplinary energy into their music and energetic live show, while Thomas brings in synths, drum machines and other electronic elements.

After releasing their powerful debut album Fongola in 2019 on indie label Transgressive Records, KOKOKO! started getting booked at music festivals around the globe, as well as on NPR's Tiny Desk series and Boiler Room. Now, the cutting-edge group is pumping up the BPM and bringing the lively Kinshasa nighttime to the rest of the world via their urgent, high-energy sophomore album, BUTU, on July 5 on Transgressive.

Read on for a chat with Thomas and Bianko about their captivating new album, the music scene in the Congo, how their music reflects Kinshasa, and much more. (Editor's note: Bianko's answers are translated and paraphrased from French by Thomas.)

What energies, sounds and themes are you harnessing on 'BUTU?'

Xavier Thomas: "Butu" means night in Lingala [one of the national languages of the DRC]. The album is all about that high energy, specific atmosphere that happens when the night falls in Kinshasa.

It's a very loud and crowded city. It gets pitch-black quite quickly because it's on the Equator. The sun sets really fast all year long. The sounds of the city kind of wake up [at night]; the generators are plugged in and the club music and evangelical church music [start] competing. All the inspirations are from all these sounds and everything that happens in the night in Kinshasa.

The band plays a lot of DIY instruments; what instruments are on this album and can you point to their specific sounds?

Xavier Thomas: There're the go-to things and then there's the found objects or the ones you can build. Simple things that are kind of ready-made, like detergent bottles — you can play it with a stick with a little bit of rubber, and it kind of makes bongo sounds with a slight natural overdrive.

And you can also build your own string instruments with what you found on the street. For example, there's plastic chairs that have metal feet, and you can do a kind of metallophone with; if you chop the tubes, you will get different pitches, etcetera. You can find something in a mechanic shop that sounds really good straight away when you hit it; metallic percussion. So that's all the different DIY instruments or found percussion that you can make or work with.

Was it mostly the same instruments as the first album, or were there some different things you were incorporating as well?

Xavier Thomas: There are different things. Also, on this one, we use a little bit more of electronics, as it's a bit more upbeat and influenced by the club and the small music production studios of Kinshasa.

There are also some field recordings. For example, on some tracks, there's horns from moto taxis that we pitched and made melodies with. But yeah, it's roughly the same instruments.

The term DIY is often attached to the band. Of course, you just talked about the instruments, but I was also curious what DIY and improvisation looks like in your music-making process and performances.

Xavier Thomas: It was an all-over DIY thing when we started. I used to make a lot of the videos. We [still] work with a small team, so we always have problems getting visas. We're doing a bit of everything just to keep going forward and traveling and to get our music everywhere. So, the DIY is not just the music, it's [all very] hands-on. Even on stage, we don't turn up with a big team, it's pretty much us at the moment.

The DIY aspect came out of necessity for the music and instrument creators, of not being able to afford to buy or rent an instrument. So it started like that, trying to make a one- or two-string guitar, a two-string bass, and a drum set. And then it went beyond that, realizing we can find original and new sounds if we're not copying existing instruments.

When I met Makara, he was doing five-hour public rehearsals six times a week on his own with 40 or 50 dancers. He had to work out all the technical problems with power cuts and amplifiers exploding. Makara still has that energy, even when we're sound checking. A lot of that DIY intuition is still coming in.

The recording process has to be DIY because you're recording in outside music studios in little compounds or in difficult neighborhoods of Kinshasa, so there's a lot of sounds in the background. You just grab the moment where the energy, the music, the inspiration feels right. That's another DIY part of the project, it's pretty much recorded outside of recording studios for the most part.

How does that also speak to access to instruments, internet and music studios for music-making in the DRC more broadly?

Xavier Thomas: Well, there's some big artists in the Congo that have a lot of money and travel to play even in the U.S. and France. A few artists have everything they want and they're very famous and wealthy. But most of the studios I've seen are a tiny room in the corner of a compound, yet people are doing the most impressive productions and recordings with very little, whether it's electronic or live music. It's very resourceful and sometimes you don't hear it, you could not imagine it would be coming from such a small studio.

I wish I could ask about every song on the album, because it feels like there's so much energy and context in each one. Can you tell me about the opening track, "Butu Ezo Ya" — the energy starts out so strong. Is there a message behind that song?

Xavier Thomas: The first track is kind of an invitation. It's saying the night's coming, be ready. We have all the sounds that we grabbed in the streets. That's the track where the horns of the motorbikes are pitched and turned into melodies. It's an invocation, an invitation, to the listener to step in the Kinshasa night because it's really something.

We wanted the opening track to be a little bit overstimulating, which is the impression you have the first time you step into the night in Kinshasa. So that's the idea, to [channel the] overwhelming street sounds that suddenly from chaos become organized and become the opener of the album to invite you to the more organized music after. [Chuckles.]

Makara Bianko: I'm inviting people to step into the night, step into the album.

The album's next track, "Bazo Banga," is really captivating as well.

Xavier Thomas: "Bazo Banga" means they are scared. Sometimes people chant it when they're protesting. It can also be used in sport events about the other teams. There's a lot of frustrations in Congo; the population is a bit abandoned by the government. Sometimes there are political things that can't be said or expressed because it's a bit dangerous. So, in this track — Makara has explained the lyrics to me before — it's a way to regain a bit of control by trying to impress the other side.

Makara Bianko: There's another angle mentioned at the end of the track: We're bringing so many new sounds that their hips are not going to hold. They are scared they are out of date, that they will not be matching our energy or be able to move because we're going too fast. During the track, I'm quoting a lot of images of why they could be scared.

Xavier Thomas: In Kinshasa, our sound is still very different. At the beginning, with all the music, art performers, people who do body performance as well, who gravitate around our music and are sometimes part of the videos; [other] people thought we were all so crazy. The music didn't fit any standards there, even though Makara has a lot of influences, more when he was younger, in more standard music like Congolese rumba or ndombolo. I think people can still be a bit scared of our style and our energy, the people we work with, it's a bit different.

In what ways is your music incorporating — as well as radically shifting — traditional and popular Congolese music?

Makara Bianko: Growing up in Kinshasa, there's a lot of Congolese rumba and nbombolo. I'm also influenced by [Congolese] folk music, really old rhythms and chants. Congo is so big that this has just been mixed in our music, but we are presenting it like it's a new recipe. It doesn't taste like what you're used to even though the ingredients are there. There's also influences [in our music] from outside countries like Angola or South Africa.

Xavier Thomas: What struck me the most when I first met Makara at this concert — from my Occidental angle — he has a very punk energy. Even though people aren't listening to punk music in Kinshasa, Makara would stick his mic in the speakers and play with feedback, and he has a very powerful voice and sometimes a very threatening singing tone. It was not influenced from punk; it was his own energy, his own frustration.

I think music helps express the frustration a lot of people have in Congo, and people see that in him, through his anger and when he talks about things people encounter on the street that they can relate to. So yeah, some of the old folk music is there as influences, but it's very important to him to not do the same thing that a lot of artists have done for the last 40 years and to bring something new.

What's going on in Kinshasa and the DRC in terms of electronic music? Are there other DIY electronic acts coming up?

Xavier Thomas: There's a lot of electronic music now, I think the big scenes are in South Africa or Nigeria for big pop electronic music. Congo used to influence a lot of West Africa and Central Africa and now Nigeria and South Africa have quite strong industries, so sometimes there's a bit of that influence.

With more Congolese rhythms for electronic music, you can have the whole range from very pop to very alternative. In the neighborhood where we started, there's a few more bands coming up now with DIY instruments who play a bit more like folk music from the Equator region in the north of the country. In Europe, I've noticed three bands since we started that now work with more DIY instruments. There's a music producer, P2N, from the southeast of Congo who makes repetitive electronic music in a kind of hypnotic, dance way.

The band has been touring quite a bit since the first album. Locally, are you an active part of a scene, or is it more like you're doing something different there and bringing that around the world?

Xavier Thomas: We're still quite unique in Kinshasa, and if we play there it would be more of a block party. Makara has a lot of dancers in his crew, and dancers would join from the youngest at the beginning [of the show] to the more experienced, bridging between classic Congolese dance and more contemporary dance. There's a lot of theater in the dance as well.

When we play there, it's still alternative. Once in a while we might play a bigger stage, but we play out [of the country] way more in front of way more people. We try not to play too often [here]. It's a huge city, so it can be tricky with the power cuts and everything. It's more of the art scene and people from the performance art school and dancers who gather if we do an event in Kinshasa, it's not huge crowds.

You've performed on some pretty big platforms, as well as at global music festivals. What goes into your energetic live performance; is there improvisation?

Xavier Thomas: It's key that we are still incredibly passionate, and we feel the music and leave a lot of space for improvisation. Then we can surprise each other, even during a gig. One track can be one length or double the next time, depending on the feeling, the crowd, the sound system and the time we play.

Usually, people end up really moving, sometimes without realizing. We don't spare any energy. You end up drenched in sweat. I think because our excitement is real, the music is not over-rehearsed. We're still always excited at every show. I think people can feel that it's not staged. There can be unexpected things happening, which keeps us energetic, motivated and surprised on stage.

How does the band usually feel after a performance? Is it a cathartic experience?

Xavier Thomas: Well, we have our kind of ceremonial thing. We usually talk together at the beginning; we gather and stick our heads together, and we say where we are and what we want to achieve. At the end of the concert, the whole hour or so feels like it's passed by really quick, and you're still left with that rhythm or energy, even though you might be super tired, sometimes traveling and playing every day. Sometimes we have more energy at the end. At the beginning, we feel tired, and then the energy really comes in, and we feel super energized and super sharp and really awake at the end. It's good for us.

What does Kinshasa sound like to you?

Xavier Thomas: For Makara and I, to explain to somebody who's never been to Kinshasa, it's a very sonic city. I've never seen [anything like it]. It's so crowded; I think it's 15 million or 18 million people now. [Editor's note: 17 million is the latest estimate.] Everybody lives on the ground floor. There aren't too many high buildings, so the density of people is very high. For this reason, it's visually a bit crowded and overwhelming with people, cars, colors and everything.

Therefore, to be noticed or stand out, everybody needs to have their own little signal or jingle. You can tell who's around you with eyes closed. A nail polish vendor would just bang two little glass polish bottles; that sound carries far away and they have their rhythm. People who sell SIM cards have a loop on their megaphone.

Sound is how to be noticed; how to sell yourself, what's your role, what's your identity. That's obviously, without talking about music and sound systems. Churches have their own huge sound systems and they can clash with the club in front. Also something very typical in Kinshasa; it goes to the fullest, to the max, everything is used at its highest potential. The sound is pushed in overdrive and distorted because you want to be louder than the next person. It's all these little sound signals that can tell exactly who's around you or sometimes where you are as well. For me, that's the sound, plus the traffic.

Wow. It must be so different going somewhere more remote, or just where it's quieter. It must feel almost like something's wrong.

Xavier Thomas: There's not many moments with silence because at night the city is still alive. People like to go out. You can have a church next to you with a full live band and a huge PA sound system at 3 a.m. Quiet moments are rare.

Makara: It's hard to deal with silence. I don't feel comfortable in silence because I've never really experienced it.

Latest News & Exclusive Videos

Behind Ryan Tedder's Hits: Stories From The Studio With OneRepublic, Beyoncé, Taylor Swift & More

Crowder Performs "Grave Robber"

NCT 127 Essential Songs: 15 Tracks You Need To Know From The K-Pop Juggernauts

5 Rising L.A. Rappers To Know: Jayson Cash, 310babii & More

Why Elliott Smith's 'Roman Candle' Is A Watershed For Lo-Fi Indie Folk

Photo: Emmanuel Oyeleke

interview

Tekno Talks New Music, Touring America & His "Elden Ring" Obsession

Ahead of his Back Outside tour, which hits the U.S. June 22, Nigerian artist Tekno details the origins of his name and sound, as well as his predictions for the future of African music on a global stage.

It takes a lot of guts to declare yourself the "King of Afro-pop," but Tekno has the hits to back it up.

The Nigerian artist is a staple of the country’s Afrobeats scene, responsible for massive hits such as "Pana" (over 66 million Spotify streams). He’s collaborated with massive artists across the world, starting in 2012 when he enlisted Davido for his breakout single "Holiday." He’s also entered the studio with the likes of Drake and Swae Lee, and Billie Eilish is a professed fan.

Despite this, Tekno hasn’t quite reached the levels of fame that colleagues WizKid and Burna Boy have stateside, but that may be about to change. He’s touring extensively across the U.S. this summer as part of his Back Outside Tour, supporting his 2023 album The More The Better. Tekno also recently inaugurated a label partnership with Mr. Eazi-owned emPawa Africa, defecting from SoundCloud.

The video for his latest single, "Wayo," features the artist as a cab driver going through relationship problems. It's a perfect example of Tekno’s classic pan-African pop, with romantic lyrics and a sweetly melodic sound.

GRAMMY.com caught up with Tekno ahead of his tour, which kicks off June 22 in Columbus, Ohio, to chat about his new music, career goals, and a surprising video game obsession.

You recently released a new single. Tell us a little bit about "Wayo?"

"Wayo" is basically me just tapping into my roots sound, the original pan-African Tekno sound. Our music has morphed and just grown into so many different sounds over the years. And it's very easy to forget that this sound existed before all this music that's playing right now. So I had to deep dive into that. That's basically how I describe "Wayo," I call it a basic Tekno love song. Like it's basically how I started really.

I don’t know if you’re aware that there’s an entire genre of music called "Techno?"

Yes, yes, it’s close to house music.

They’re pretty close. Actually, techno music was invented here in America by Black musicians in Detroit.

Oh, wow. Yeah, people don’t really listen to the techno genre out here yet. They prefer more melodic and groovy music.

So in that case, I did want to ask you about your artist name. Because if people don’t really listen to techno music in Africa, where did your name come from?

I was much younger, and I was looking for a name while I was in church. I’m a Christian, so I was looking for a name that had some form of Christianity to it, even though I knew I wanted to be a secular artist. And then I found this name, "tekno," and it's Hebrew, it means something like "God's people" or "God's word." It's spelt a little bit differently, I can't really remember. But I just liked the meaning of it, and the name stuck with me. And that's how I started calling myself "Tekno."

You've declared yourself the "King of Afro-Pop." Why do you consider yourself to be the king of Afro-pop, and why that instead of the King of Afrobeats or another label like that?

It's more of a personal thing in a way. My favorite artist of all time, forever, will always be Michael Jackson. And Michael Jackson is the King of Pop. So when I named myself the "King of Afro-Pop," it’s because I like Michael Jackson, but it's also because I'm the king of Afro-f—ing-pop. So the name just kind of has a good ring to it.

I want to talk a little bit about partnering with Mr. Eazi; why did you decide to join EmPawa? What do you think the partnership holds for your future, and for the future of music in Africa?

I just love making music so much, that's the goal for me. And I've gone from camp to camp, level to level, and after a while it just starts to wear on you. I don't want to just keep moving from Triple MG to Universal to SoundCloud; I want my own thing that’s a little more permanent. And Eazi is not just my friend, he's my brother. We've been talking about this for years, about doing business together.

There are reasons why it made so much sense for us to come together, but I don't want to share everything. But I like being a priority. If I'm on SoundCloud, I don't want to be on a list of 27 artists where I'm maybe number 18 and my music doesn't get the focus it needs. Like, say I put out a song, and everyone on SoundCloud has gone on holiday. And I'm not aware because I'm Nigerian, I don't know that this day or that day is a holiday in the States. But working with a brother and a team that is home, where we know the system and we understand the culture, it's just way, way better. Because we know ourselves, we know our culture. So working with a brother that has this amazing setup at EmPawa, it just made so much sense.

Read more: Mr. Eazi’s Gallery: How The Afrobeats Star Brought His Long-Awaited Album To Life With African Art

You've collaborated with some American artists before, and Billie Eilish said she is a big fan of yours. Is there anyone in the U.S.-UK ecosystem that you would consider a dream collaboration?

I’d definitely love to work with Billie Eilish. 100 percent. But Drake would always be my favorite collaboration, just because we've been in the studio together. We've talked about it. You know, if I start something I want to see it finished.

He's just an inspiration to the business. Drake, he makes you know that you gotta work, because as big as Drake is he works harder than everybody else. That’s not to say that I wouldn’t love to collaborate with so many other artists whose music I really love.

Are you following the beef between Drake and Kendrick at all?

That was so good, man. I didn't consider that a beef, because when I would watch boxers in the ring fight, let’s say I'm watching Mayweather vs. Pacquiao, it doesn't matter who I'm a fan of. It doesn't matter who wins, I'm entertained.

As a big fan of music, I enjoyed every Drake song and I enjoyed every single Kendrick Lamar song. But if you ask me who I prefer, I would always pick sides and choose. But was I entertained? I definitely was, for sure.

How is working with Americans different from working with Africans? What are the distinctions you find between the two?

Back in Nigeria we don't work in big studios, we work at home. Like, if I want to work with Wizkid I would probably go to his house, or he would come to mine, and we would make music there. But if I'm going to work with Travis Scott, we're gonna go to the studio. If I'm working with Billie Eilish we're gonna go to the studio.

You’re touring North America this year. Do you have any expectations, or anything you’re looking forward to?

I'm just happy to be back outside. I went through this period where I had lost my voice in 2019. And after that happened, and I went through surgery in New York, Corona[virus] happened right after.

And in this whole period, I kind of just stayed away from how much I worked and how much I put out music in the past. I feel like I got used to not being active, so I haven't necessarily been performing for a while. That’s why this tour in the U.S. is called The Back Outside Tour. Because for a long time I haven't been outside, I haven’t been performing, I’ve just been at home.

I like to game [and] I like to make music. I make so much music, but I feel like being home has kind of restricted the amount of music I put out. Because anytime I’m outside, I just get this feeling like I want to conquer the world, I want to do more; I want to put out more.

I want to do more than I've done in the past. So this tour for me is just getting back outside, just getting myself out there and just being on the road heavy. You get lazy if you stay home for too long; we’re habitual creatures. So now I have the mindset that I have to forcefully keep myself out there and just be outside. I'm gonna be touring for three months in the U.S. That's a long time.

You mentioned you’re a gamer. What have you been playing recently?

Recently I've been on "GTA V"; the online is extremely good. Just because it has this plethora of radio stations where while you're gaming you can still bask in this vast playlist. And it’s just fun because you get to play with people around the world. I [also] have this Nigerian community I play with. It's like a way to just be around the people even though I'm in the house, so it's really lovely. And "Call of Duty" is a great one too. But my all time favorite I would say is "Elden Ring." I got locked into Elden Ring for like eight weeks.

Amapiano has really become the dominant sound coming out of Africa in recent years. What do you think will be next?

Tekno sound! They miss it! My sound is like "Game of Thrones," season one to seven.

Not season eight.

Not season eight. I didn’t say that, you said that! [Laughs.]

Basically, I’m not saying amapiano isn’t beautiful music, I’m not saying Nigerians haven’t found a way to evolve it in a way that’s different from the South African type. The South African sound will always be the original one, and every time you record on a South African amapiano beat, you can just tell the difference in the sound. It’s their culture, they own it.

But we [Nigerians] are extremely good at taking your sound and putting our own flavor on it. It’s still your sound, but we play with it. So I feel like it’s been two years of the same [amapiano] and after a while people are gonna want another type of song. I’m not saying Amapiano will go away all of a sudden, it’ll never go away. But people want that pan-African sound. The local rhythm. And Tekno got that.

Learn more: 11 Women Pushing Amapiano To Global Heights: Uncle Waffles, Nkosazana Daughter, & More

Can you go into detail? How do you describe this pan-African sound?

These are songs that always tell a story, it’s never just random. "Wayo" is talking about, "If I invest in my love, would I get a return?" "I no come do wayo" means I'm not trying to play games. I'm serious. If I invest in this love, would I get it back? This thing we call love? Do you truly believe in it? Or you're just with me for the sake of dating somebody?

This type of music always has a deep rooted message in the melodies; it's not just like a regular party thing. There's always a good tale behind the sweet melodies. So like, no, no matter how new school our music goes, this type of sound would always be this type of sound. You're not taking it where. It’s culture.

The video for "Wayo" shows you driving a cab. Did you ever have to hold down a day job like that before you became a successful musician?

Oh my god. I've been a houseboy. I catered for four little kids. They were so stubborn, man, that was the hardest thing I've done in my life. [Laughs.] That would have to be a different interview. I've worked in churches, too. I grew up from a very humble background and I'm grateful to God that I experienced that.

Tems On How 'Born In The Wild' Represents Her Story Of "Survival" & Embracing Every Part Of Herself

Photo: Chris Polk/FilmMagic

list

How Amy Winehouse's 'Back To Black' Changed Pop Music Forever

Ahead of the new Amy Winehouse biopic 'Back To Black,' reflect on the impact of the album of the same name. Read on for six ways the GRAMMY-winning LP charmed listeners and changed the sound of popular music.

When Amy Winehouse released Back To Black in October 2006, it was a sonic revelation. The beehive-wearing singer’s second full-length blended modern themes with the Shangri-Las sound, crafting something that seemed at once both effortlessly timeless and perfectly timed.

Kicking off with smash single "Rehab" before blasting into swinging bangers like "Me & Mr. Jones," "Love Is A Losing Game," and "You Know I’m No Good," Black To Black has sold over 16 million copies worldwide to date and is the 12th best-selling record of all time in the United Kingdom. It was nominated for six GRAMMY Awards and won five: Record Of The Year, Song Of The Year, Best New Artist, Best Female Pop Vocal Performance, and Best Pop Vocal Album.

Winehouse accepted her golden gramophones via remote link from London due to visa problems. At the time, Winehouse set the record for the most GRAMMYs won by a female British artist in a single year, though that record has since been broken by Adele, who won six in 2011.

Written in the wake of a break-up with on-again, off-again flame Blake Fielder-Civil, Black To Black explores heartbreak, grief, and infidelity, as well as substance abuse, isolation, and various traumas. Following her death in 2011, Back To Black became Winehouse’s most enduring legacy. It remains a revealingly soulful message in a bottle, floating forever on the waves.

With the May 17 release of Sam Taylor-Johnson’s new (and questionably crafted) Winehouse biopic, also titled Back To Black, it's the perfect time to reflect on the album that not only charmed listeners but changed the state of a lot of popular music over the course of just 11 songs. Here are five ways that Back To Black influenced music today.

She Heralded The Arrival Of The Alt Pop Star

When Amy Winehouse hit the stage, people remarked on her big voice. She had classic, old-time torch singer pipes, like Sarah Vaughn or Etta Jones, capable of belting out odes to lost love, unrequited dreams, and crushing breakups. And while those types of singers had been around before Winehouse, they didn’t always get the chance — or grace required — to make their kind of music, with labels and producers often seeking work that was more poppy, hook-packed, or modern.

The success of Back To Black changed that, with artists like Duffy, Adele, and even Lady Gaga drawing more eyes in the wake of Winehouse’s overwhelming success. Both Duffy and Adele released their debut projects in 2007, the year after Back To Black, bringing their big, British sound to the masses. Amy Winehouse's look and sound showed other aspiring singers that they could be different and transgressive without losing appeal.

Before she signed to Interscope in 2007, "nobody knew who I was and I had no fans, no record label," Gaga told Rolling Stone in 2011. "Everybody, when they met me, said I wasn’t pretty enough or that my voice was too low or strange. They had nowhere to put me. And then I saw [Amy Winehouse] in Rolling Stone and I saw her live. I just remember thinking ‘well, they found somewhere to put Amy…’"

If an artist like Winehouse — who was making records and rocking styles that seemed far outside the norm — could break through, then who’s to say someone else as bold or brassy wouldn’t do just as well?

It Encouraged Other Torch Singers In The New Millenium

Back To Black might have sounded fun, with swinging cuts about saying "no" to rehab and being bad news that could seem lighthearted to the casual listener. Dig a little deeper, though, and it’s clear Winehouse is going through some real romantic tumult.

Before Back To Black was released, Fielder-Civil had left Winehouse to get back together with an old girlfriend, and singer felt that she needed to create something good out of all those bad feelings. Songs like "Love Is A Losing Game" and "Tears Dry On Their Own" speak to her fragile emotional state during the making of the record, and to how much she missed Fielder-Civil. The two would later marry, though the couple divorced in 2009.

Today, young pop singers like Olivia Rodrigo, Taylor Swift, and Selena Gomez are lauded for their songs about breakups, boyfriends, and the emotional damage inflicted by callous lovers. While Winehouse certainly wasn’t the first to sing about a broken heart, she was undoubtedly one of the best.

It Created A Bit Of Ronsonmania

Though Mark Ronson was already a fairly successful artist and producer in his own right before he teamed with Winehouse to write and co-produce much of Back To Black, his cred was positively stratospheric after the album's release. Though portions of Back To Black were actually produced by Salaam Remi (who’d previously worked with Winehouse on Frank and who was reportedly working on a follow-up album with her at the time of her death), Ronson got the lion’s share of credit for the record’s sound — perhaps thanks to his his GRAMMY win for Best Pop Vocal Album. Winehouse would even go on to guest on his own Version record, which featured the singer's ever-popular cover of "Valerie."

In the years that followed, Ronson went on to not only produce and make his own funky, genre-bending records, but also to work with acts like Adele, ASAP Rocky, and Paul McCartney, all of whom seemingly wanted a little of the retro soul Ronson could bring. He got huge acclaim for the funk-pop boogie cut "Uptown Funk," which he wrote and released under his own name with help from Bruno Mars, and has pushed into film as well, writing and producing over-the-top tracks like A Star Is Born’s "Shallow" and Barbie’s "I’m Just Ken." To date, he’s been nominated for 17 GRAMMY Awards, winning eight.

Ronson has always acknowledged Winehouse’s role in his success, as well, telling "BBC Breakfast" in 2010, "I've always been really candid about saying that Amy is the reason I am on the map. If it wasn't for the success of Back To Black, no one would have cared too much about Version."

Amy Showcased The Artist As An Individual

When the GRAMMY Museum hosted its "Beyond Black - The Style of Amy Winehouse" exhibit in 2020, Museum Curator and Director of Exhibitions Nicholas Vega called the singer's sartorial influence "undeniable." Whether it was her beehive, her bold eyeliner, or her fitted dresses, artists and fans had adopted elements of Winehouse’s Back To Black style into their own fashion repertoire. And though it’s the look we associate most with Winehouse, it was actually one she had truly developed while making the record, amping up her Frank-era low-slung jeans, tank tops, and polo shirts with darker eyeliner and much bigger hair, as well as flirty dresses, vibrant bras, and heels.

"Her stylist and friends were influential in helping her develop her look, but ultimately Amy took bits and pieces of trends and styles that she admired to create her own look," Vega told GRAMMY.com in 2020. While rock ‘n’ rollers have always leaned into genre-bending styles, Winehouse’s grit is notable in the pop world, where artists typically have a bit more of a sheen. These days, artists like Miley Cyrus, Billie Eillish, and Demi Lovato are willing to let their fans see a bit more of the grit — thanks, no doubt, to the doors Winehouse opened.

Winehouse also opened the door to the beauty salon and the tattoo studio, pushing boundaries with not just her 14 different vintage-inspired tattoos — which have become almost de rigeur these days in entertainment — but also with her signature beehive-like bouffant, which hadn’t really been seen on a popular artist since the ‘60s.It’s a frequent look for contemporary pop divas, popping up on artists like Ariana Grande, Lana Del Rey, and Dua Lipa.

The Dap-Kings Got The Flowers They Deserved

Six of Back To Black’s 11 songs, including "Rehab," got their "retro" sound via backing from the Dap-Kings, a Brooklyn-based soul act Ronson recruited for the project.

While Winehouse’s lyrics were mostly laid down in London, the Dap-Kings did their parts in New York. Ronson told GRAMMY.com in 2023 that the Dap-Kings "brought ['Rehab'] to life," saying, "I felt like I was floating because I couldn’t believe anybody could still make that drum sound in 2006." Winehouse and the Dap-Kings met months later after the record was released, and recorded "Valerie." The band later backed Winehouse on her U.S. tour.

Though the Dap-Kings were known in hip musical circles for their work with late-to-success soul sensation Sharon Jones, Back To Black’s immense success buoyed the listening public’s interest in soul music and the Dap-Kings' own profile (not to mention that of their label, Daptone Records).

"Soul music never went away and soul lovers never went away, but they’re just kind of closeted because they didn’t think it was commercially viable," Dap-Kings guitarist Binky Griptite said in the book It Ain't Retro: Daptone Records & The 21st Century Soul Revolution. "Then, when Amy’s record hit, all the undercover soul fans are like, I’m free. And then that’s when everybody’s like, Oh, there’s money in it now."

The success of Back To Black also seems to have firmly cemented the Dap-Kings in Ronson’s Rolodex, with the group’s drummer Homer Steinweiss, multi-instrumentalist Leon Michaels, trumpeter Dave Guy, and guitarist/producer Tom Brenneck appearing on many of his projects; the Dap-Kings' horns got prominent placement in "Uptown Funk."

Amy Exposed The Darker Side Of Overwhelming Success

Four years after Winehouse died, a documentary about her life was released. Asif Kapadia’s Amy became an instant rock-doc classic, detailing not only Winehouse’s upbringing, but also her struggles with fame and addiction. It won 30 awards after release, including Best Documentary Feature at the 88th Academy Awards and Best Music Film at the 58th GRAMMY Awards.

It also made a lot of people angry — not for how it portrayed Winehouse, but for how she was made to feel, whether by the British press or by people she considered close. The film documented Winehouse’s struggles with bulimia, self-harm, and depression, and left fans and artists alike feeling heartbroken all over again about the singer’s passing.

The documentary also let fans in on what life was really like for Winehouse, and potentially for other artists in the public eye. British rapper Stormzy summed it up well in 2016 when he told i-D, "I saw the [documentary, Amy] – it got me flipping angry... [Amy’s story] struck a chord with me in the sense that, as a creative, it looks like on the outside, that it’s very ‘go studio, make a hit, go and perform it around the world, champagne in the club, loads of girls’. But the graft and the emotional strain of being a musician is very hard. No one ever sees that part."

These days, perhaps because of Winehouse’s plight or documentaries like Amy, the music-loving population seems far more inclined to give their favorite singers a little grace, whether it’s advocating for the end of Britney Spears’ conservatorship or sympathizing with Demi Lovato’s personal struggles. Even the biggest pop stars are still people, and Amy really drove that point home.

We Only Said Goodbye With Words: Remembering Amy Winehouse 10 Years Later

Photo: David Corio/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

list

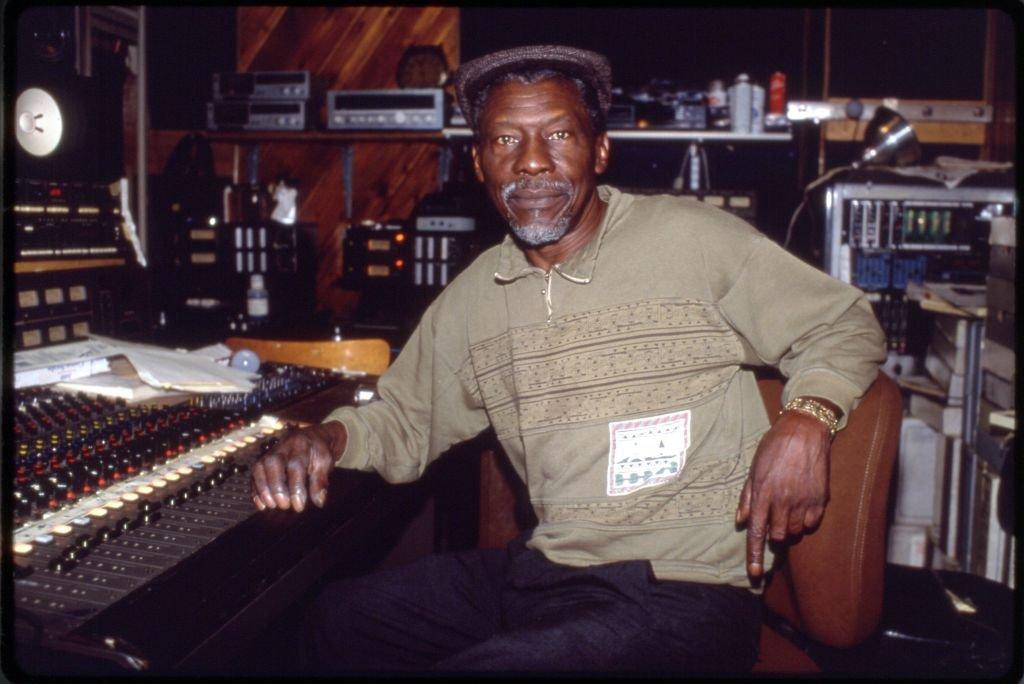

Remembering Coxsone Dodd: 10 Essential Productions From The Architect Of Jamaican Music

Regarded as Jamaica’s Motown, Coxsone Dodd's Studio One helped launch the careers of legends such as Burning Spear, Toots and the Maytals, and the Wailers. In honor of the 20th anniversary of Dodd’s passing, learn about 10 of his greatest productions.

On April 30, 2004, producer Clement Seymour "Sir Coxsone" Dodd — an architect in the construction of Jamaica’s recording industry — was honored at a festive street renaming ceremony on Brentford Road in Kingston, Jamaica. The bustling, commercial thoroughfare at the geographical center of Kingston was rechristened Studio One Blvd. in recognition of Coxsone’s recording studio and record label.

Dodd is said to have acquired a former nightclub at 13 Brentford Road in 1962; his father, a construction worker, helped him transform the building into the landmark studio. In 1963 Dodd installed a one-track board and began recording and issuing records on the Studio One label.

Dodd’s Studio One was Jamaica’s first Black-owned recording facility and is regarded as Jamaica’s Motown because of its consistent output of hit records. Studio One releases helped launch the careers of numerous ska, rocksteady and reggae legends including Bob Andy, Dennis Brown, Burning Spear, Alton Ellis, the Gladiators, the Skatalites, Toots and the Maytals, Marcia Griffiths, Sugar Minott, Delroy Wilson and most notably, the Wailers.

At the street renaming ceremony, a jazz band played, speeches were given in tribute to Dodd’s immeasurable contributions to Jamaican music and many heartfelt memories from the studio’s heyday were shared. In the culmination of the late afternoon program, Dodd, his wife Norma, and Kingston’s then mayor Desmond McKenzie unveiled the first sign bearing the name Studio One Blvd. Four days later, on April 4, 2002, Coxsone Dodd suffered a fatal heart attack at Studio One. His productions, however, live on as benchmarks within the island’s voluminous and influential music canon.

Born Clement Seymour Dodd on Jan. 26, 1932, he was given the nickname Sir Coxsone after the star British cricketer whose batting skills Clement was said to match. As a teenager, Dodd developed a fondness for jazz and bebop that he heard beamed into Jamaica from stations in Miami and Nashville and the big band dances he attended in Kingston. Dodd launched Sir Coxsone’s Downbeat sound system around 1952 with the impressive collection of R&B and jazz discs he amassed while living in the U.S., working as a seasonal farm laborer.

Many sound system proprietors traveled to the U.S. to purchase R&B records — the preferred music among their dance patrons and key to a sound system’s following and trumping an opponent in a sound clash. With the birth of rock and roll in the mid-1950s, suitable R&B records became scarce. Jamaica’s ever-resourceful sound men ventured into Kingston studios to produce R&B shuffle recordings for sound system play.

Recognizing there was a wider market for this music, Dodd pressed up a few hundred copies of two sound system favorites for general release, the instrumental "Shuffling Jug" by bassist Cluett Johnson and his Blues Blasters and singer/pianist Theophilus Beckford’s "Easy Snapping," both issued on Dodd’s first label, Worldisc. (Some historians recognize "Easy Snapping" as a bridge between R&B shuffle and the island’s Indigenous ska beat; others cite it as the first ska record.) When those discs sold out within a few days, other soundmen followed Dodd’s lead and Jamaica’s commercial recording industry began to flourish.

"Before then, the only stuff released commercially were mento records that were recorded here, but our sound really hit so we kept on recording. When I heard 'Easy Snapping,' I said 'Oh my gosh!'" Coxsone recalled in a 2002 interview for Air Jamaica's Skywritings at Kiingston’s Studio One. "I thank God for that moment."

Dodd was the first producer to enlist a house band, pay them a weekly salary rather than per record. Together, they had an impressive run of hits in the ska era in the early ‘60s; during the rocksteady period later in the decade, Dodd ceded top ranking status to long standing sound system rival (but close family friend) turned producer Duke Reid. (Still, Studio One released the most enduring instrumentals or rhythm tracks, also known as riddims, of the period.) As rocksteady morphed into reggae circa 1968, Dodd triumphed again with consistent releases of exceptional quality.

In 1979 armed robbers targeted the Brentford Rd premises several times. Dodd left Jamaica and established Coxsone’s Music City record store/recording studio in Brooklyn, dividing his time between New York and Kingston. Reissues of Dodd’s music via Cambridge, MA based Heartbeat Records, beginning in the mid 1980s, followed by London’s Soul Jazz label in the 2000s, and most recently Yep Roc Records in Hillsborough, NC, have helped introduce Studio One’s masterful work to new generations of fans.

"The best time I’ve ever had was when I acquired my studio at 13 Brentford Rd. because you can do as many takes until we figured that was it," Coxsone reflected in the 2002 interview. "God gave me a gift of having the musicians inside the studio to put the songs together. In the studio, I always thought about the fans, making the music more pleasing for listening or dancing. What really helped me was having the sound system, you play a record, and you weren’t guessing what you were doing, you saw what you were doing."

To commemorate the 20th anniversary of Coxsone Dodd’s passing, read on for a list of 10 of his greatest productions.

The Maytals - "Six and Seven Books of Moses" (1963)

In 1961 at the dawn of Jamaica’s ska era, Toots Hibbert met singers Nathaniel "Jerry" Matthias and Henry "Raleigh" Gordon and they formed the Maytals. The trio released several hits for Dodd including the rousing, "Six and Seven Books of Moses," a gospel-drenched ska track that’s essentially a shout out of a few Old Testament chapters.

Moses is credited with writing five chapters, as the lyrics state, "Genesis and Exodus, Leviticus and Numbers Deuteronomy," but "the Six and Seven books" are in question. Many Biblical scholars say Moses wasn’t the scribe, believing those chapters, including phony spells and incantations to keep evil spirits away, were penned in the 18th or 19th century.

Nevertheless, there’s a real magic formula in The Maytals’ "Six and Seven Books of Moses": Toots’ electrifying preacher at the pulpit delivery melds with elements of vintage soul, gritty R&B, and classic country; Jerry and Raleigh provide exuberant backing vocals and seminal ska outfit and Studio One’s first house band, the Skatalities deliver an irresistible, jaunty ska rhythm with a sophisticated jazz underpinning.

The Wailers - "Simmer Down" (1964)

A flashback scene in the biopic Bob Marley: One Love depicts the Wailers (then a teenaged outfit called the Juveniles) approaching Dodd for a recording opportunity; Dodd inexplicably points a gun at them as they recoil in terror. Yet, there isn’t any mention of such an inappropriate and unprovoked action from the producer in the various books, documentaries, interviews and other accounts of the Wailers’ audition for Dodd.

The Wailers’ first recording session with Dodd in July 1964, however, yielded the group’s first hit single "Simmer Down." At that time, the Wailers lineup consisted of founding members Bob Marley, Bunny Livingston (later Wailer) and Peter Tosh alongside singers Junior Braithwaite and (the sole surviving member) Beverley Kelso. When Junior left for the U.S., Dodd appointed Marley as the group’s lead singer.

The energetic "Simmer Down" cautions the impetuous rude boys to refrain from their hooligan exploits. The Skatalites’ spirited horn led intro, thumping jazz infused bass and fluttering sax solo, enhances Marley’s youthful lead and the backing vocalists’ effervescence. The Wailers would spend two years at Studio One and record over 100 songs there, including the first recording of "One Love" in 1965; by early 1966, they would have five songs produced by Dodd in the Jamaica Top 10.

Alton Ellis -"I’m Still In Love" (1967)

Jamaica’s brief rocksteady lasted about two years between 1966-1968, but was an exceptionally rich and influential musical era. The rocksteady tempo maintained the accentuated offbeat of its ska predecessor, but its slower pace allowed vocal and musical arrangements, affixed in heavier, more melodic basslines.

Alton Ellis is considered the godfather of rocksteady because he had numerous hits during the era and released "Rock Steady," the first single to utilize the term for producer Duke Reid. Ellis initially worked with Dodd in the late 1950s then returned to him in 1967. The evergreen "I’m Still in Love" was penned by Alton as a plea to his wife as their marriage dissolved: "You don’t know how to love me, or even how to kiss me/I don’t know why." Supporting Alton’s elegant, soulful rendering of heartbreak, Studio One house band the Soul Vendors, led by keyboardist Jackie Mittoo, provide an engaging horn-drenched rhythm, epitomizing what was so special about this short-lived time in Jamaican music.

"I’m Still In Love" has been covered by various artists including Sean Paul and Sasha, whose rendition reached No. 14 on the Billboard Hot 100 in 2004. Beyoncé utilized Jamaican singer Marcia’s Aitken’s 1978 version of the tune in a TV ad announcing her 2018 On The Run II tour with Jay-Z. In February 2024, Jennifer Lopez sampled "I’m Still in Love" for her single "Can’t Get Enough."

Bob Andy - "I’ve Got to Go Back Home" (1967)

The late Keith Anderson, known professionally as Bob Andy, arrived at Studio One in 1967. He quickly became a hit-making vocalist, and an invaluable writer for other artists on the label. He penned several hits for Marcia Griffiths including "Feel Like Jumping," "Melody Life" and "Always Together," the latter their first of many hit recordings as a duo.

A founding member of the vocal trio the Paragons, "I’ve Got to go Back Home" was Andy’s first solo hit and it features sublime backing vocals by the Wailers (Bunny, Peter and Constantine "Vision" Walker; Bob Marley was living in the USA at the time.) Set to a sprightly rock steady beat featuring Bobby Ellis (trumpet), Roland Alphonso (saxophone) and Carlton Samuels’ (saxophone) harmonizing horns, Andy’s lyrics poignantly depict the challenges endured by Jamaica’s poor ("I can’t get no clothes to wear, can’t get no food to eat, I can’t get a job to get bread") while expressing a longing to return to Africa, a central theme within 1970s Rasta roots reggae.

The depth of Andy’s lyrics expanded the considerations of Jamaican songwriters and one of his primary influences was Bob Dylan. "When I heard Bob Dylan, it occurred to me for the first time that you don’t have to write songs about heart and soul," Andy told Billboard in 2018. "Bob Dylan’s music introduced me to the world of social commentary and that set me on my way as a writer."

Dawn Penn - "You Don’t Love Me" (1967)

Dawn Penn’s plaintive, almost trancelike vocals and the lilting rock steady arrangement by the Soul Vendors transformed Willie Cobbs’ early R&B hit "You Don’t Love Me," based on Bo Diddley’s 1955 gritty blues lament "She’s Fine, She’s Mine," into a Jamaican classic. The song’s shimmering guitar intro gives way to the forceful drum and bass with Mittoo’s keyboards providing an understated yet essential flourish.

In 1992 Jamaica’s Steely and Clevie remade the song, featuring Penn, for their album Steely and Clevie Play Studio One Vintage. The dynamic musician/production duo brought their mastery (and 1990s technological innovations) to several Studio One classics with the original singers. Heartbeat released "You Don’t Love Me" as a single and it reached No. 58 on the Billboard Hot 100.

Several artists have reworked Penn’s rendition or sampled the Soul Vendors’ arrangement including rapper Eve on a collaboration with Stephen and Damian Marley. Rihanna recruited Vybz Kartel for an interpretation included on her 2005 debut album Music of the Sun, while Beyoncé performed the song on her I Am world tour in 2014 and recorded it in 2019 for her Homecoming: The Live Album. In 2013, Los Angeles-based Latin soul group the Boogaloo Assassins brought a salsa flavor to Penn's tune, creating a sought-after DJ single.

The Heptones - "Equal Rights" (1968)

"Every man has an equal right to live and be free/no matter what color, class or race he may be," sings an impassioned Leroy Sibbles on "Equal Rights," the Heptones’ stirring plea for justice.

Harmony vocalist Earl Morgan formed the group with singer Barry Llewellyn in the early '60s and Sibbles joined them a few years later. The swinging bass line, played by Sibbles, anchors a stunning rock steady rhythm track awash in cascading horns, and blistering percussion patterns akin to the akete or buru drums heard at Rastafari Nyabinghi sessions.

Besides leading the Heptones’ numerous hit singles during their five-year stint at Studio One, Sibbles was a talent scout, backing vocalist, resident bassist and the primary arranger, alongside Jackie Mittoo. Sibbles’ progressive basslines are featured on numerous Studio One nuggets (many appearing on this list) and have been sampled or remade countless times over the decades on Jamaican and international hits.

In a December 2023 interview Sibbles echoed a complaint expressed by many who worked at Studio One: Dodd didn’t fairly compensate his artists and the (uncredited) musicians produced the songs while Dodd tended to business matters. "When we started out, we didn’t know about the business, and what happened, happened. But as you learn as you go along," he said. "I have registered what I could; I am living comfortably so I am grateful."

The Cables - "Baby Why" (1968)

Formed in 1962 by lead singer Keble Drummond and backing vocalists Vincent Stoddart and Elbert Stewart, the Cables — while not as well-known as the Wailers, the Maytals or the Heptones — recorded a few evergreen hits at Studio One, including the enchanting "Baby Why."

Keble’s aching vocals lead this breakup tale as he warns the woman who left that she’ll soon regret it. The simple story line is delivered via a gorgeous melody that’s further embellished by Vincent and Elbert’s superb harmonizing, repeatedly cooing to hypnotic effect "why, why oh, why?"

Coxsone is said to have kept the song for exclusive sound system play for several months; when he finally released it commercially, "Baby Why" stayed at No. 1 for four weeks.

"Baby Why" is notable for another reason: although the Maytals’ "Do The Reggay" marks the initial use of the word reggae in a song, "Baby Why" is among a handful of songs cited as the first recorded with a reggae rhythm (reggae basslines are fuller and reggae’s tempo is a bit slower than its rocksteady forerunner.) Other contenders for that historic designation include Lee "Scratch Perry’s "People Funny Boy," the Beltones’ "No More Heartache," and Larry Marshall and Alvin Leslie’s delightful "Nanny Goat."

Burning Spear - "Door Peeper" (1969)

Hailing from the parish of St. Ann, Jamaica, Burning Spear was referred to Studio One by another St. Ann native, Bob Marley. Spear’s first single for Studio One "Door Peeper" (also known as "Door Peep Shall Not Enter") recorded in 1969, sounded unlike any music released by Dodd and was critical in shaping the Rastafarian roots reggae movement of the next decade.

The song’s biblically laced lyrics caution informers who attempt to interfere with Rastafarians, considered societal outcasts at the time in Jamaica, while Spear’s intonation to "chant down Babylon" creates a haunting mystical effect, supported by Rupert Willington’s evocative, deep vocal pitch, a throbbing bass, mesmeric percussion and magnificent horn blasts.

As Spear told GRAMMY.com in September 2023, "When Mr. Dodd first heard 'Door Peep' he was astonished; for a man who’d been in the music business for so long, he never heard anything like that." Dodd’s openness to recording Rasta music, and allowing ganja smoking on the premises (but not in the studio) when his competitors didn’t put him in the forefront at the threshold of the roots reggae era.

"Door Peeper" was included on Burning Spear’s debut album, Studio One Presents Burning Spear, released in 1973 and remains a popular selection in the legendary artist’s live sets.

Joseph Hill - "Behold The Land" (1972)

In the October 1946 address Behold The Land by W. E. B. DuBois at the closing session of the Southern Youth Legislature in Columbia, South Carolina, the then 78-year-old celebrated author and activist urges Black youth to fight for racial equality and the civil rights denied them in Southern states. The late Joseph Hill’s 1972 song of the same name, possibly influenced by Dubois’ words, is a powerful reggae missive exploring the atrocities of the transatlantic slave trade from which descended the discriminations DuBois described.

Hill was just 23 when he wrote/recorded "Behold The Land," his debut single as a vocalist. Hill’s haunting timbre summons the harrowing experience with the wisdom and emotional rendering of an ancestor: "For we were brought here in captivity, bound in links and chains and we worked as slaves and they lashed us hard." Hill then gives praise and asks for repatriation to the African motherland, "let us behold the land where we belong."

The Soul Defenders — a self contained entity but also a Studio One house band with whom Hill made his initial recordings as a percussionist — provide a persistent, bass heavy rhythm that suitably frames Hill’s lyrical gravitas, as do the melancholy hi-pitched harmonies.

In 1976 Hill formed the reggae trio Culture and the next year they catapulted to international fame with their apocalyptic single "Two Sevens Clash," which prompted Dodd to finally release "Behold The Land." Culture would re-record "Behold The Land" over the years including for their 1978 album Africa Stand Alone and the song received a digital remastering in 2001.

Sugar Minott - "Oh Mr. DC" (1978)

In the mid-1970s singer Lincoln "Sugar" Minott began writing lyrics to classic 1960s Studio One riddims, an approach that launched his hitmaking solo career and further popularized the practice of riddim recycling — which is still a standard approach in dancehall production. Sugar, formerly with the vocal trio The African Brothers, penned one of his earliest solo hits "Oh, Mr. DC" to the lively beat of the Tennors’ 1967 single "Pressure and Slide" (itself a riddim originally heard, at a faster pace, underpinning Prince Buster’s 1966 "Shaking Up Orange St.")

"Oh, Mr. DC" is an authentic tale of a ganja dealer returning from the country with his bag of collie (marijuana); the DC (district constable/policeman) says he’s going to arrest him and threatens to shoot if he attempts to run away. Sugar explains to the officer that selling herb is how he supports his family: "The children crying for hunger/ I man a suffer, so you’ve got to see/it’s just collie that feed me." To underscore his urgent plea, Sugar wails in an unforgettable melody, "Oh, oh DC, don’t take my collie."

The irresistibly bubbling bassline of the riddim nearly obscures the song’s poignant depiction of Jamaica’s harsh economic realities and the potential risk of imprisonment, or worse, that the island’s ganja sellers faced at the time. Sugar’s revival of a Studio One riddim and reutilization of 10 Studio One riddims for each track of his 1977 album Live Loving brought renewed interest to the treasures that could be extracted from Mr. Dodd’s vaults.

Special thanks to Coxsone Dodd’s niece Maxine Stowe, former A&R at Sony/Columbia and Island Records, who started her career at Coxsone’s Music City, Brooklyn.

How 'The Harder They Come' Brought Reggae To The World: A Song By Song Soundtrack Breakdown