Photo: Frazer Harrison/Getty Images

news

Hip-Hop History On Full Display During A Star-Studded Tribute To The 50th Anniversary Of Hip-Hop Featuring Performances By Missy Elliott, LL COOL J, Ice-T, Method Man, Big Boi, Busta Rhymes & More | 2023 GRAMMYs

The landmark performance honoring the genre’s diverse history featured performances from a long line of hip-hop’s powerful history, from Run-DMC to LL COOL J, Salt-N-Pepa, Missy Elliott to Future.

With hip-hop marking half a century of powerful contribution to the music world in 2023, the 65th GRAMMY Awards proved the ideal opportunity to honor the genre’s storied legacy.

At the 2023 GRAMMYs, an unimaginably deep lineup of contributors to that tradition graced the stage, drawn from a wide swath of hip-hop’s history — from progenitors to today’s up-and-coming stars, from the East Coast boom to the swagger of the Dirty South, performing hits and cult classics from throughout the decades. On a constantly shifting stage with a bevy of backup dancers, the Recording Academy's tribute to hip-hop seemly had the entire Crypto.com arena on their feet.

As the performance’s curator Questlove put it on the red carpet, it was a "family reunion." After an introduction from LL COOL J, the Roots set up shop behind the performers, while Black Thought narrated the massive lineup’s spread across three acts.

“I founded Rock The Bells to elevate the creators of Hip-Hop culture and to make sure the timeless stories were told correctly. This performance gave us the opportunity to honor the music of the last 50 years and further uplift the culture, in line with the proud work we are doing through RTB,” LL COOL J said about the special tribute in a statement to GRAMMY.com “The process of working with Questlove and the GRAMMY producers was truly a joy. I’m deeply inspired that I was able to help bring together this incredible and iconic group of artists to the stage on Sunday. This special moment will sit with me for a long time to come.”

The performance’s first act comprised legends from hip-hop’s early days, the arena thrilled by the likes of Grandmaster Flash and Run DMC, and absolutely exploding when Chuck D & Flavor Flav hit the stage for "Rebel Without a Pause," the Public Enemy members getting Lizzo and Adele swaying together.

After a quick transition, LL and Black Thought helped the stage transport into the late ‘80s and ‘90s, bringing together the likes of De La Soul, Geto Boys’ Scarface, and Ice-T, with Jay-Z rapping along with Method Man from his table in the audience. But this second section of the performance also included two of the biggest eruptions of the night. The first came in the form when Busta Rhymes recreated his incredibly nimble flow from "Look at Me Now"; the tribute’s second act ended with Missy Elliott, the legend blitzing through snippets and samples of a variety of hits complete with a full dance crew.

The third act then entered the ‘00s with Nelly’s "Hot In Herre", swirling forward into the present from there. Rising star GloRilla thrilled the young crowd with "F.N.F. (Let’s Go)" (nominated this evening for Best Rap Performance), injecting even more adrenaline into the mix. And with LL COOL J surrounded by a blend of artists drawn from across the decades, the entire arena roared in celebration of these incredible 50 years, leaving a certainty that the next 50 will be even stronger.

Check out the complete list of winners and nominees at the 2023 GRAMMYs

Photo: Aaron J. Thornton

interview

Celebrating Missy Elliott: How The Icon Changed The Sound, Look & Language Of Hip-Hop

In celebration of Missy Elliott's incredible legacy — and very first headlining tour, which kicks off July 4 — GRAMMY.com spoke with Missy's colleagues and collaborators for an insider’s view on what makes the four-time GRAMMY winner unique.

We’re fortunate enough to be living in the middle of a Missy Elliott resurgence — not that she ever went away.

Three decades into her groundbreaking career, Missy is readying her very first headlining tour, which begins July 4 in Vancouver, British Columbia. The Out of This World Tour runs through August and features her longtime collaborators Timbaland, Busta Rhymes, and Ciara.

The fact that it is her first headlining tour may be surprising, given that she’s been on the scene since debuting with the group Sista in the mid-1990s, and has been a chart-topping star since becoming a solo artist in 1997.

The hip-hop icon released her last full-length album, The Cookbook, nearly two decades ago but time hasn’t diminished her influence at all. In fact, we’re all still catching up to the futuristic vision that Missy and Timbaland introduced to the world in the late 1990s in their songs and videos.

Missy began her career as a member of Sista, which was a part of the Swing Mob, a musical collective working under Jodeci’s DeVanté Swing. That crew included a number of future world-changers, including Missy, Timbaland, Ginuwine, Tweet, Stevie J., and two legends who have since passed on, Magoo and Static Major. After Sista was dropped from their label, Missy, by all accounts, would have been perfectly happy to settle into a life as a songwriter and producer. But something bigger was beckoning.

Persuaded by Elektra’s Sylvia Rhone with the promise of her own label, Missy agreed to turn in one album as a solo artist. That album, 1997’s Supa Dupa Fly, made Missy not just a star but an icon, and changed the course of her life. It began a career that, over a quarter-century later, found her inducted into both the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and the Songwriters Hall of Fame — she was the first female rapper ever to be nominated for the latter.

And that’s just the beginning of the accolades. There are the four GRAMMY wins and head-spinning 22 nominations. She was also honored alongside Dr. Dre, Lil Wayne (who has not been shy about calling Missy his favorite rapper), and the woman who gave Missy her first solo record deal, Sylvia Rhone, at 2023’s Black Music Collective’s Recording Academy Honors event. Missy was also a key participant in the GRAMMYs tribute to a half-century of hip-hop that same year.

Throughout it all, Missy has remained humble. When speaking to GRAMMY.com in 2022, she reflected on how she and longtime collaborator Timbaland had no idea of their impact at the time.

"We really just came out with a sound that we had been doing for some time, but we had no clue that it would be game changing, that we would change the cadence — the sound of what was happening at that time," she said. "No clue!"

"Her whole existence is based on moving us and influencing us," says her longtime manager Mona Scott-Young. "She wants to be able to touch people."

And that she has. To celebrate the Missy-aissance, GRAMMY.com spoke with Missy's colleagues and collaborators for an insider’s view on the course of her career and what makes the four-time GRAMMY winner unique.

The quotes and comments used in this feature were edited for clarity and brevity.

Missy’s Impact Began With Her First Guest Verse

The first time many people took note of Missy Elliott was her verse on the 1996 remix of Gina Thompson’s "That Thing You Do."

Gina Thompson (singer): I was in the process of completing my first album, Nobody Does It Better. Actually, it was complete. So what happened was, my A&R at the time, Bruce Carbone at Mercury Records, wanted to have Puffy do the remix.

Puffy was like, "We have this person that's really talented. Her name's Missy, and she used to be with the group Sista, and she's a phenomenal writer. She's working with a lot of other artists, she’s definitely the next big thing in the R&B/hip-hop world." We were like, cool.

I believe we actually heard it over the speaker phone in Bruce’s office. I know that I said that I loved it, and I felt her style was unique and different. It grew on me in a great way. I just felt like it was a smash. She definitely had added a great touch to it. I was super-excited about it.

Merlin Bobb (former Executive Vice President, Elektra Records): I was blown away by the simple fact that I knew she was a great songwriter. But when I heard her rhyming, I thought it was the most unique style that I had heard in some time.

Digital Black (former member of Playa, part of the Swing Mob): A lot of people only knew her as a writer or an R&B artist, but when she came on that Gina Thompson record with that rap, it changed everything. It allowed her to be even more herself.

Mona Scott-Young (manager): Oh my God, have you heard that song? It’s her ability to use expression and evoke emotion without even using words. She said, "He he he haw," and we all found a new way to bounce. There was something fun and magical and different that spoke to what we would come to know was this incredibly vivid imagination that would take us places sonically and visually that we didn’t even know we needed to be.

She Changed The Sound Of Hip-Hop With Her Debut LP

Missy’s first solo album, Supa Dupa Fly, came out the following year. It gave new energy to a hip-hop scene that was still reeling from the deaths of 2Pac and Biggie.

Anne Kristoff (former Vice President of PR, Elektra): She 100 percent did not want to be an artist. She's like, "I'm not an artist. I want to be Diane Warren. I'm going to write the songs. I'm going to be behind the scenes."

Merlin Bobb: I started talking to her regarding being an artist. She was totally against it. "No, I want to be a songwriter." And also, just to be honest, [Sista] had been dropped from Elektra prior to my conversations with her, so she wasn't too eager, I think, to jump back aboard.

It took about six or seven months of us discussing ways to do this. I spoke to Sylvia [Rhone, then-head of Elektra], and I said, "She's an incredible songwriter. Let's offer her a production deal or a label deal where she can not only just look at herself as an artist, but at the same time develop and nurture artists under her own banner." Sylvia thought it was a great idea.

We both talked to Missy about it, and she said, "Okay, I'll do one album." I was ecstatic because she was writing some great songs, but she also gave us her first album, which was, needless to say, a classic.

Kathy Iandoli (author, "God Save the Queens: The Essential History of Women in Hip-Hop and Baby Girl: Better Known as Aaliyah"): In God Save the Queens, I referred to her as the Andy Warhol of hip-hop, in the sense that she took the art and the cultural aspect of it, and she just put this spin and interpretation of the art that no one had ever really done prior.

With Missy’s arrival around ‘97, we were at a point in time where hip-hop was in a complete state of confusion. We did not know where it was going to go. Missy made high art hip-hop that was commercially accessible. And for that, she changed the entire game.

Gina Thompson: When she had her first project with the whole vision — not only her sound, but her songwriting style, the look — everyone was like, "This girl went out on edge. I'm gonna do a little bit of the same thing and not be so worried if I don't sound so average, what people are going to think. Because she's out on the edge doing it." And I promise you, ever since she came out, that you started hearing a lot more of female rappers tweaking their voices.

Lenny Holmes (guitarist): In hip-hop, everybody would think that it's a whole bunch of computer generated stuff. Missy Elliott does not approach it like that. She loves live instrumentation, but she likes to take bits and pieces of it. She simplifies it, and it is placed uniquely in the track at certain points. That's what makes up the structure of the song.

Mona Scott-Young: Everything from the way she looked to what she was talking about to the way she delivered that music and what she represented in terms of being nonconforming, not looking like the other female rappers of the day — I think all of those elements were the perfect lightning in a bottle. The way she rode that beat, both lyrically and with her delivery, was very, very different from everything else that we were hearing.

Read more: Revisiting 'Supa Dupa Fly' At 25: Missy Elliott Is Still Inspired By Her Debut Record

She Reinvented The Music Video

You can’t think of Missy Elliott without picturing her iconic music videos, many done in collaboration with director Hype Williams.

Brian Greenspoon (former International Publicist, Elektra): I mean, she came out of the gate wearing a garbage bag, and made it the coolest thing anyone had ever seen.

Merlin Bobb: She said, if I put out this album — initially we were talking about a single deal, but we went into an album — there’s two things very important to me: the dance aspect and the visual aspect.

Kathy Iandoli: The thing that I really loved about Missy's music videos, she was a big budget music video person. She got the men's music video budget.

Anne Kristoff: When you think about the "Rain" video — I'm just guessing, I don't want to put words in her mouth — but I think when she saw that the vision in her head could become real out in the world, that anything she could think of could happen, that maybe it made it a little more fun for her to be an artist. I hope.

Digital Black: Missy is one of the funniest people you’ll ever meet. People maybe don't know. She loves joking. So that was just her being her.

Gina Thompson: You started seeing a lot of people doing certain robotic-type images or moves in their videos to almost mimic her "Supa Dupa Fly." She’s the creator of that.

Earl Baskerville (manager/producer): Missy would get with the director, and she would sit there and go over the whole treatment. A lot of the visuals came from her. She was very hands on. Today, you can shoot a video in four or five hours. But Missy’s video shoots was so long, I used to hate it. We would be there fifteen hours for a three minute video!

She Was Avant-Garde But Still Pop

Missy’s musical and visual style was like nothing anyone had ever seen. Yet she still became a star. How did she manage to be both innovative and accessible?

Kathy Iandoli: You can't make something that the general public can't access, or speak over their heads.

Digital Black: Even if you said it sounded weird, it still had some soulfulness to it. I think that was what allowed her to touch so many different people.

Merlin Bobb: When you have an artist that stands out, but it doesn't go over your head musically, artistically, lyrically, then it works. People, when they heard and experienced something new and fresh that was easy to digest, but it was unique, they gravitated to it.

Brian Greenspoon: How was it sold to a mass audience? I mean, the sound was breakthrough. What Timbaland was doing with drum sounds, and the way they were building these very sparse rhythms and sound beds, they were breaking ground. But the thing that worked is that they had these incredible songs that Missy was writing and that she had these incredible featured artists on.

Gina Thompson: To try to figure out what her brain is doing, I’ve been gave that up.

Earl Baskerville: Nobody could figure out what we were doing, because they couldn’t understand the sound.

Lenny Holmes: Her rhythmic style of how she would do the vocals was just unheard of. Like, doubling up accents. The things that she started doing — you would hear a deejay do a scratch on a record. You would not hear a singer do it. I was like, What in the world?

Anne Kristoff: She was doing these really creative things that no one else was doing visually. And the sound was different than whatever everyone else was doing. So it wasn't a hard sell for the press.

She Was A Master At Working With Other Artists

Missy was far more than just a solo star. All throughout her career, she continued her first love: writing and producing for other artists — including Ciara, Aaliyah, Destiny’s Child, and Whitney Houston.

Lenny Holmes: Missy had a great relationship with singers and rappers, because she could do both. A lot of people don’t know, but Missy can sing. So when we worked with groups that had singing parts on them, a lot of times she would go ahead and lay down the guide track for the actual artist to sing.

Kathy Iandoli: Missy just really understood the artists that she worked with. She saw their strengths, and she helped them utilize them to the best of their capabilities.

Angelique Miles (former music publishing executive): She was able to relate to the artist and express that artist. She was able to customize and express that artist's story. Whatever she wrote for 702 didn’t sound like what she wrote for Whitney Houston.

Digital Black: She was good at listening to the artist, seeing what they do, and then, how can you enhance what they do well? Those are the best records. She was great at tailor-making records for people, just from her doing her due diligence on learning who the artist is. Not just going in, "I’m Missy, I can write whatever." I'm gonna write something specifically for you that enhances what you’ve already done.

Merlin Bobb: She would have made an incredible A&R person. I would have hired her back then. She was able to come up with lyrics and melodies and songs and chords and production that to me stood out. She worked with both male and female artists. She really knew how to get an artist not only to sing a great song, but to sing very uniquely and in their own way, because she was a great vocal production coach.

Mona Scott-Young: She's always listening beyond what we hear. Even if there's a song an artist has [that she’s not involved with], she'll say, "Yeah, I would have done this thing differently with this artist. Because if you listen to what she did on this one part of the song, you can hear that there's more range there. But for some reason they didn't push her to go there." That to me is just one of the things that makes her such a great producer and star finder, because she always is looking for what more they can do and how they can challenge themselves to be better.

Earl Baskerville: She had signed an artist that I used to manage named Mocha. And she told Mocha to go in there and just rap. I think Mocha might have did 30-something bars, 60 bars. know. Missy listened to all of the stuff she did, took it, and dissected it. She went in there and took eight bars, not from the beginning of the track — I don’t know where she found it, in the middle or something — and put it on the Nicole Wray record "Make It Hot." When Mocha comes in, that’s actually the middle of the verse somewhere! That was crazy to me.

Her First Love Was Always Songwriting

Through it all, Missy’s strength remained (and remains) her songwriting. But what makes her songs stand out, and stand the test of time?

Earl Baskerville: Missy didn’t want to be an artist. She just wanted to be a songwriter.

Merlin Bobb: Her songwriting was very soulful, but it also had great melodic edge to it. They’re very realistic lyrics to a young scene that was happening in R&B and hip-hop at the time. So it was somewhat of a fusion of R&B and hip-hop lyrically, and she just had a very strong sense of melody and great hook lines.

Mona Scott-Young: She wasn't talking about the same thing that we were hearing from a lot of the other females in the genre at the time — overt sexuality and material possessions and that kind of stuff. She was engaging, having a good time lyrically, and holding her own with her male counterparts.

She was giving us music that was great, and it didn't matter that it was coming from a female. She was kind of this androgynous being that was delivering great music. You listen to the song, you just want to party.

Read more: Missy Elliott Makes History As First Female Rapper Nominated For Songwriters Hall Of Fame

She Changed The Artists Who Came After Her

As with all major innovations, it didn’t take long after Missy broke big for her influence to be felt.

Kathy Iandoli: The special relationship between Aaliyah, Missy, and Timbaland was the fact that together they all created a new sound that would set the standard of hip-hop and what we now define as alt-R&B. They invented a new subgenre. It was something that Missy was able to continue along and then create a sound on her own terms.

Gina Thompson: Many people were trying to emulate her whole different style.

Lenny Holmes: [Were people copying her?] Most definitely. But there's only one Missy. And I got to say, there’s only one Timbaland too. You hear that trademark voice or the trademark lick, and you just know that's them.

Brian Greenspoon: I think she influenced just about everybody that came after her. The sound of hip-hop changed after her and Timbaland dropped that music. The way the people produced their drum sounds and their beats, the use of hi hats, it all changed based on Missy and Timbaland.

Merlin Bobb: Most hip-hop/R&B collaborations at that time were hip-hop records with vocal hooks from R&B artists. She kind of flipped it, where she worked from the R&B side and made the vocals and the production more hip-hop friendly.

Mona Scott-Young: Her whole existence is based on moving us and influencing us. She wants to be able to touch people. So when we see artists who you can hear or see the influence, then you know that she's done her job.

There's so many artists — Flyana Boss, a little bit Cardi, a little bit Nicki. They all, I think, have been influenced by Missy, her look, her sound, in one way, shape or form. And that is the greatest compliment, to inspire a generation and see them take what you've done to another level. But then she's constantly also evolving and keeping everyone on their toes.

Learn more: 8 Ways Aaliyah Empowered A Generation Of Female R&B Stars

Considering Missy And Her Legacy

Everyone interviewed for this piece had so much love for Missy. Here’s a small sample.

Brian Greenspoon: Missy is one of the most professional, talented, creative artists I've ever had the luck to work with. I'm happy to see that she is being recognized for being the icon that we all saw that she was becoming back then.

Lenny Holmes: Even today, in whatever we're doing, we use what we've learned from Missy Elliott. It’s mixed in whatever we do. It’s amazing what she has done for herself, but she has definitely helped people along the way, and we will forever be grateful to her.

Digital Black: She's a one-of-one, God-given talent. She earned every award, every accolade, accomplishment. Her work ethic was phenomenal, and nothing was given. Big sis earned everything, and I just want to say I love her, and it's been a pleasure and an honor to be a part of her career.

Kathy Iandoli: There’s so much of the art that we have right now that we have to thank her for.

Mona Scott-Young: This has been an incredible journey. I always talk about being incredibly blessed to have had the opportunity to play a role when you have somebody like her who has touched so many people globally and whose music and entire presence hold this special place in fans’ hearts.

Every day it's just about, how do we continue to push forth, break boundaries, challenge ourselves to do things bigger and better than we did it the last go round.

Explore The Artists Who Changed Hip-Hop

50 Artists Who Changed Rap: Jay-Z, The Notorious B.I.G., Dr. Dre, Nicki Minaj, Kendrick Lamar, Eminem & More

Hip-Hop Just Rang In 50 Years As A Genre. What Will Its Next 50 Years Look Like?

Watch Outkast Humbly Win Album Of The Year For 'Speakerboxxx/The Love Below' In 2004 | GRAMMY Rewind

A Brief History Of Hip-Hop At 50: Rap's Evolution From A Bronx Party To The GRAMMY Stage

GRAMMY Museum To Celebrate 50 Years Of Hip-Hop With 'Hip-Hop America: The Mixtape Exhibit' Opening Oct. 7

Watch Eminem Show Love to Detroit And Rihanna During Best Rap Album Win In 2011 | GRAMMY Rewind

Listen To GRAMMY.com's 50th Anniversary Of Hip-Hop Playlist: 50 Songs That Show The Genre's Evolution

14 New Female Hip-Hop Artists To Know In 2023: Lil Simz, Ice Spice, Babyxsosa & More

6 Artists Expanding The Boundaries Of Hip-Hop In 2023: Lil Yachty, McKinley Dixon, Princess Nokia & More

Watch 41 Bring The Hype With A Cover Of DMX's Hit "Party Up (Up In Here)" | Hip-Hop Re:Defined

The 10 Most Controversial Samples In Hip-Hop History

Watch Lauryn Hill Win Best New Artist At The 1999 GRAMMYs | GRAMMY Rewind

19 Concerts And Events Celebrating The 50th Anniversary Of Hip-Hop

Founding Father DJ Kool Herc & First Lady Cindy Campbell Celebrate Hip-Hop’s 50th Anniversary

A Guide To New York Hip-Hop: Unpacking The Sound Of Rap's Birthplace From The Bronx To Staten Island

A Guide To Southern California Hip-Hop: Definitive Releases, Artists & Subgenres From L.A. & Beyond

10 Crucial Hip-Hop Albums Turning 30 In 2023: 'Enter The Wu-Tang,' 'DoggyStyle,' 'Buhloone Mindstate' & More

The Nicki Minaj Essentials: 15 Singles To Showcase Her Rap And Pop Versatility

11 Hip-Hop Subgenres To Know: From Jersey Club To G-Funk And Drill

5 Essential Hip-Hop Releases From The 2020s: Drake, Lil Baby, Ice Spice, 21 Savage & More

A Guide To Southern Hip-Hop: Definitive Releases, Artists & Subgenres From The Dirty South

A Guide To Bay Area Hip-Hop: Definitive Releases, Artists & Subgenres From Northern California

A Guide To Texas Hip-Hop: Definitive Releases, Artists & Events

Ludacris Dedicates 2007 Best Rap Album GRAMMY To His Dad | GRAMMY Rewind

Unearthing 'Diamonds': Lil Peep Collaborator ILoveMakonnen Shares The Story Behind Their Long-Awaited Album

10 Bingeworthy Hip-Hop Podcasts: From "Caresha Please" To "Trapital"

Revisiting 'The Miseducation Of Lauryn Hill': Why The Multiple GRAMMY-Winning Record Is Still Everything 25 Years Later

Watch Asha Imuno Personalize Kendrick Lamar's "i" With A Sparkling New Chorus | Hip-Hop Re:Defined

10 Must-See Exhibitions And Activations Celebrating The 50th Anniversary Of Hip-Hop

5 Artists Showing The Future Of AAPI Representation In Rap: Audrey Nuna, TiaCorine & More

'Invasion of Privacy' Turns 5: How Cardi B's Bold Debut Album Redefined Millennial Hip-Hop

10 Songs That Show Doja Cat’s Rap Skills: From "Vegas" To "Tia Tamara" & "Rules"

Watch Olen Put A Dreamy, Melodic Spin On Childish Gambino's "Heartbeat" | Hip-Hop Re:Defined

6 Must-Watch Hip-Hop Documentaries: 'Hip-Hop x Siempre,' 'My Mic Sounds Nice' & More...

Essential Hip-Hop Releases From The 2010s: Ye, Cardi B, Kendrick Lamar & More

6 Takeaways From Netflix's "Ladies First: A Story Of Women In Hip-Hop"

How Drake & 21 Savage Became Rap's In-Demand Duo: A Timeline Of Their Friendship, Collabs, Lawsuits And More

5 Takeaways From Travis Scott's New Album 'UTOPIA'

Essential Hip-Hop Releases From The 2000s: T.I., Lil Wayne, Kid Cudi & More

Songbook: How Jay-Z Created The 'Blueprint' For Rap's Greatest Of All Time

Ladies First: 10 Essential Albums By Female Rappers

How Megan Thee Stallion Turned Viral Fame Into A GRAMMY-Winning Rap Career | Black Sounds Beautiful

How Hip-Hop Took Over The 2023 GRAMMYs, From The Golden Anniversary To 'God Did'

5 Things We Learned At "An Evening With Chuck D" At The GRAMMY Museum

Remembering De La Soul’s David Jolicoeur, a.k.a. Dave and Trugoy the Dove: 5 Essential Tracks

Catching Up With Hank Shocklee: From Architecting The Sound Of Public Enemy To Pop Hits & The Silver Screen

Meet The First-Time GRAMMY Nominee: GloRilla On Bonding with Cardi B, How Faith And Manifestation Helped Her Achieve Success

Hip-Hop's Secret Weapon: Producer Boi-1da On Working With Kendrick, Staying Humble And Doing The Unorthodox

Essential Hip-Hop Releases From The 1990s: Snoop Dogg, Digable Planets, Jay-Z & More

10 Albums That Showcase The Deep Connection Between Hip-Hop And Jazz: De La Soul, A Tribe Called Quest, Kendrick Lamar & More

Hip-Hop Education: How 50 Years Of Music & Culture Impact Curricula Worldwide

Women In Hip-Hop: 7 Trailblazers Whose Behind-The-Scenes Efforts Define The Culture

Watch Flavor Flav Crash Young MC's Speech After "Bust A Move" Wins In 1990 | GRAMMY Rewind

Essential Hip-Hop Releases From The 1980s: Slick Rick, RUN-D.M.C., De La Soul & More

Lighters Up! 10 Essential Reggae Hip-Hop Fusions

How Lil Nas X Turned The Industry On Its Head With "Old Town Road" & Beyond | Black Sounds Beautiful

9 Teen Girls Who Built Hip-Hop: Roxanne Shante, J.J. Fadd, Angie Martinez & More

Essential Hip-Hop Releases From The 1970s: Kurtis Blow, Grandmaster Flash, Sugarhill Gang & More

Killer Mike Says His New Album, 'Michael,' Is "Like A Prodigal Son Coming Home"

5 Takeaways From 'TLC Forever': Left-Eye's Misunderstood Reputation, Chilli's Motherhood Revelation, T-Boz's Health Struggles & More

Watch Eva B Perform "Sunrise In Lyari" Through The Streets Of Pakistan | Global Spin

Photo: Clarence Davis/NY Daily News Archive via Getty Images

feature

How 1994 Changed The Game For Hip-Hop

With debuts from major artists including Biggie and Outkast, to the apex of boom bap, the dominance of multi-producer albums, and the arrival of the South as an epicenter of hip-hop, 1994 was one of the most important years in the culture's history.

While significant attention was devoted to the celebration of hip-hop in 2023 — an acknowledgement of what is widely acknowledged as its 50th anniversary — another important anniversary in hip-hop is happening this year as well. Specifically, it’s been 30 years since 1994, when a new generation entered the music industry and set the genre on a course that in many ways continues until today.

There are many ways to look at 1994: lists of great albums (here’s a top 50 to get you started); a look back at what fans and tastemakers were actually listening to at the time; the best overlooked obscurities. But the best way to really understand why a single 365 three decades ago had such an impact is to narrow our focus to look at the important debut albums released that year.

An artist’s or group’s debut is their entry into the wider musical conversation, their first full statement about who they are and where in the landscape they see themselves. The debuts released in 1994 — which include the Notorious B.I.G.'s Ready to Die, Nas' Illmatic and Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik from Outkast — were notable not only in their own right, but because of the insight they give us into wider trends in rap.

Read on for some of the ways that 1994's debut records demonstrated what was happening in rap at the time, and showed us the way forward.

Hip-Hop Became More Than Just An East & West Coast Thing

The debut albums that moved rap music in 1994 were geographically varied, which was important for a music scene that was still, from a national perspective, largely tied to the media centers at the coasts. Yes, there were New York artists (Biggie and Nas most notably, as well as O.C., Jeru the Damaja, the Beatnuts, and Keith Murray). The West Coast G-funk domination, which began in late 1992 with Dr. Dre’s The Chronic, continued with Dre’s step brother Warren G.

But the huge number of important debuts from other places around the country in 1994 showed that rap music had developed mature scenes in multiple cities — scenes that fans from around the country were starting to pay significant attention to.

To begin with, there was Houston. The Geto Boys were arguably the first artists from the city to gain national attention (and controversy) several years prior. By 1994, the city’s scene had expanded enough to allow a variety of notable debuts, of wildly different styles, to make their way into the marketplace.

Read more: A Guide To Texas Hip-Hop: Definitive Releases, Artists & Events

The Rap-A-Lot label that first brought the Geto Boys to the world’s attention branched out with Big Mike’s Somethin’ Serious and the Odd Squad’s Fadanuf Fa Erybody!! Both had bluesy, soulful sounds that were quickly becoming the label’s trademark — in no small part due to their main producers, N.O. Joe and Mike Dean. In addition, an entirely separate style centered around the slowed-down mixes of DJ Screw began to expand outside of the South Side with the debut release by Screwed Up Click member E.S.G.

There were also notable debut albums by artists and groups from Cleveland (Bone Thugs-N-Harmony, Creepin on ah Come Up), Oakland (Saafir and Casual), and of course Atlanta — more about that last one later.

1994 Saw The Pinnacle Of Boom-Bap

Popularized by KRS-One’s 1993 album Return of the Boom Bap, the term "boom bap" started as an onomatopoeic way of referring to the sound of a standard rap drum pattern — the "boom" of a kick drum on the downbeat, followed by the "bap" of a snare on the backbeat.

The style that would grow to be associated with that name (though it was not much-used at the time) was at its apex in 1994. A handful of primarily East Coast producers and groups were beginning a new sonic conversation, using innovations like filtered bass lines while competing to see who could flip the now standard sample sources in ever-more creative ways.

Most of the producers at the height of this style — DJ Premier, Buckwild, RZA, Large Professor, Pete Rock and the Beatnuts, to name a few — worked on notable debuts that year. Premier produced all of Jeru the Damaja’s The Sun Rises in the East. Buckwild helmed nearly the entirety of O.C.’s debut Word…Life. RZA was responsible for Method Man’s Tical. The Beatnuts took care of their own full-length Street Level. Easy Mo Bee and Premier both played a part in Biggie’s Ready to Die. And then there was Illmatic, which featured a veritable who’s who of production elites: Premier, L.E.S., Large Professor, Pete Rock, and Q-Tip.

The work the producers did on these records was some of the best of their respective careers. Even now, putting on tracks like O.C.’s "Time’s Up" (Buckwild), Jeru’s "Come Clean" (Premier), Meth’s "Bring the Pain" (RZA), Biggie’s "The What" (Easy Mo Bee), or Nas’ "The World Is Yours" (Pete Rock) will get heads nodding.

Major Releases Balanced Street Sounds & Commercial Appeal

"Rap is not pop/If you call it that, then stop," spit Q-Tip on 1991’s "Check the Rhime." Two years later, De La Soul were adamant that "It might blow up, but it won’t go pop." In 1994, the division between rap and pop — under attack at least since Biz Markie made something for the radio back in the ‘80s — began to collapse entirely thanks to the team of the Notorious B.I.G. and his label head and producer Sean "Puffy" Combs.

Biggie was the hardcore rhymer who wanted to impress his peers while spitting about "Party & Bulls—." Puff was the businessman who wanted his artist to sell millions and be on the radio. The result of their yin-and-yang was Ready to Die, an album that perfectly balanced these ambitions.

This template — hardcore songs like "Machine Gun Funk" for the die-hards, sing-a-longs like "Juicy" for the newly curious — is one that Big’s good friend Jay-Z would employ while climbing to his current iconic status.

Solo Stars Broke Out Of Crews

One major thing that happened in 1994 is that new artists were created not out of whole cloth, but out of existing rap crews. Warren G exploded into stardom with his debut Regulate… G Funk Era. He came out of the Death Row Records axis — he was Dre’s stepbrother, and had been in a group with a pre-fame Snoop Dogg. Across the country, Method Man sprang out of the Wu-Tang collective and within a year had his own hit single with "I’ll Be There For You/You’re All I Need To Get By."

Anyone who listened to the Odd Squad’s album could tell that there was a group member bound for solo success: Devin the Dude. Keith Murray popped out of the Def Squad. Casual came out of the Bay Area’s Hieroglyphics.

Read more: A Guide To Bay Area Hip-Hop: Definitive Releases, Artists & Subgenres From Northern California

This would be the model for years to come: Create a group of artists and attempt, one by one, to break them out as stars. You could see it in Roc-a-fella, Ruff Ryders, and countless other crews towards the end of the ‘90s and the beginning of the new millennium.

Multi-Producer Albums Began To Dominate

Illmatic was not the first rap album to feature multiple prominent producers. However, it quickly became the most influential. The album’s near-universal critical acclaim — it earned a perfect five-mic score in The Source — meant that its strategy of gathering all of the top production talent together for one album would quickly become the standard.

Within less than a decade, the production credits on major rap albums would begin to look nearly identical: names like the Neptunes, Timbaland, Premier, Kanye West, and the Trackmasters would pop up on album after album. By the time Jay-Z said he’d get you "bling like the Neptunes sound," it became de rigueur to have a Neptunes beat on your album, and to fill out the rest of the tracklist with other big names (and perhaps a few lesser-known ones to save money).

The South Got Something To Say

If there’s one city that can safely be said to be the center of rap music for the past decade or so, it’s Atlanta. While the ATL has had rappers of note since Shy-D and Raheem the Dream, it was a group that debuted in 1994 that really set the stage for the city’s takeover.

Outkast’s Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik was the work of two young, ambitious teenagers, along with the production collective Organized Noize. The group’s first video was directed by none other than Puffy. Biggie fell so in love with the city that he toyed with moving there.

Outkast's debut album won Best New Artist and Best New Rap of the Year at the 1995 Source Awards, though the duo of André 3000 and Big Boi walked on stage to accept their award to a chorus of boos. The disrespect only pushed André to affirm the South's place on the rap map, famously telling the audience, "The South got something to say."

Read more: A Guide To Southern Hip-Hop: Definitive Releases, Artists & Subgenres From The Dirty South

Outkast’s success meant that they kept on making innovative albums for several more years, as did other members of their Dungeon Family crew. This brought energy and attention to the city, as did the success of Jermain Dupri’s So So Def label. Then came the "snap" movement of the 2000s, and of course trap music, which had its roots in aughts-era Atlanta artists like T.I. and producers like Shawty Redd and DJ Toomp.

But in the 2010s a new artist would make Atlanta explode, and he traced his lineage straight back to the Dungeon. Future is the first cousin of Organized Noize member Rico Wade, and was part of the so-called "second generation" of the Dungeon Family back when he went by "Meathead." His world-beating success over the past decade-plus has been a cornerstone in Atlanta’s rise to the top of the rap world. Young Thug, who has cited Future as an influence, has sparked a veritable ecosystem of sound-alikes and proteges, some of whom have themselves gone on to be major artists.

Atlanta’s reign at the top of the rap world, some theorize, may finally be coming to an end, at least in part because of police pressure. But the city has had a decade-plus run as the de facto capital of rap, and that’s thanks in no small part to Outkast.

Why 1998 Was Hip-Hop's Most Mature Year: From The Rise Of The Underground To Artist Masterworks

Photo: Leon Bennett/Getty Images for Netflix

interview

For Questlove, "A GRAMMY Salute To 50 Years Of Hip-Hop" Is Crucial For Rap's Legacy

When Questlove worked on the Hip-Hop 50 revue at the 2023 GRAMMYs, the experience was so stressful that he lost two teeth. But he didn't balk at the opportunity to co-produce a two-hour special; the task was too important.

Today, Public Enemy's 1988 album It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back is correctly viewed as a watershed not just for hip-hop, but all of music. But when Questlove's father overheard him playing it, it didn't even sound like music to him.

"He happened to pass my room while 'Night of the Living Baseheads' came on and he had a look of disgust and dismay, like he caught me watching porn," the artist born Ahmir Thompson tells GRAMMY.com. "He literally was like, 'Dude, when you were three, I was playing you Charlie Parker records, and I was playing you real singers and real arrangers, and this is what you call music? All those years I wasted on private school and jazz classes. This is what you like?'

"I couldn't explain to him: 'Dad, you don't understand. Your entire boring-ass record collection downstairs is now being redefined in this very album. Everything you've ever played is in this record,'" he says. "If my dad — who was relatively cool and hip, but just getting older — couldn't understand it, then I know there's a world of people out there that are really just like, whatever."

That nagging reality has powered him ever since — whether he's co-leading three-time GRAMMY winners the Roots, authoring books and liner notes, or directing Oscar-winning films.

And that path led straight to Questlove's role as a executive producer for "A GRAMMY Salute To 50 Years Of Hip-Hop," which will air Sunday, Dec. 10, from 8:30 to 10:30 p.m. ET and 8:00 to 10:00 p.m. PT on the CBS Television Network, and stream live and on demand on Paramount+.

Questlove makes no bones about it: working on that 12-minute Hip-Hop 50 revue at the 2023 GRAMMYs was taxing. So taxing, in fact, that he lost two teeth due to the psychological pressure. But he soldiered on, and the result is an inspiring rush of a two-hour special.

"The thing that really motivated me — Look, man, roll up your sleeves and run through this mud — was like, if there ever was going to be a hip-hop time capsule, a lot of the participants in this show are somewhere between the ages of 20 and 60, and everybody's still kind of in their prime," he says.

"So that way,” Questlove continues, “in 2030, 2040, 2050, when our great, great, great, great grandkids are born and they want to look up someone, this'll probably be one of the top five things they look up. And I wanted to be a part of that."

Read on for a rangey interview with Questlove about his role in "A GRAMMY Salute To 50 Years of Hip-Hop," in all its dimensions.

Explore More Of "A GRAMMY Salute to 50 Years of Hip-Hop"

6 Highlights From "A GRAMMY Salute To 50 Years Of Hip-Hop": Performances From DJ Jazzy Jeff & The Fresh Prince, Queen Latifah, Common & More

Here’s All The Performers And Songs Featured At "A GRAMMY Salute To 50 Years Of Hip-Hop"

Watch Backstage Interviews From "A GRAMMY Salute To 50 Years Of Hip-Hop" Featuring LL Cool J, Questlove, Warren G & E-40, And Many More

How DJ Jazzy Jeff & The Fresh Prince Created The Ultimate Prototype For The Producer/Rapper Duo

For Questlove, "A GRAMMY Salute To 50 Years Of Hip-Hop" Is Crucial For Rap's Legacy

How Lin-Manuel Miranda Bridged The Worlds Of Broadway & Hip-Hop

How To Watch "A GRAMMY Salute To 50 Years Of Hip-Hop": Air Date, Performers Lineup, Streaming Channel & More

Full Performer Lineup For "A GRAMMY Salute To 50 Years Of Hip-Hop" Announced: Roddy Ricch, Chance The Rapper, Nelly, Coi LeRay, Akon, Mustard & More Artists Added

DJ Jazzy Jeff And The Fresh Prince To Reunite Onstage At "A GRAMMY Salute To 50 Years Of Hip-Hop"

"A GRAMMY Salute To 50 Years Of Hip-Hop" Airs Sunday, Dec. 10: Save The Date

This interview has been edited for clarity.

What can you tell me about your involvement in "A GRAMMY Salute To 50 Years Of Hip-Hop"?

I could be the guy that complains and complains and complains and complains: Man, I wish somebody would dah, dah, dah. Man, somebody needs to dah, dah, dah. And then the universe the whole time is poking you in the stomach like a dog. You think you're going to be drumming for life — like, that's your job.

So I went through this period where I just hated the lay of the land. And now people are like, "Well, the door is open if you want to come and see if you could change it." And for me, it was just important to.

And at first, I was really skeptical about this because even when I was an artist, my peers all the time would — I say in air quotes jokingly, but it's like, man, I know they're serious — they would just call me a suit. Whenever someone's called a suit in a sitcom or it is like, that's always the bad guy. Or especially for me that's known for all this artistry.

But for me, it's like, I can either just sit on the sidelines and watch this thing slowly kind of go in a direction that I don't want it to go. And often with the history of Black music in America, we're innovating this stuff, but we're really not behind the scenes in power positions to control it or to decide what direction it is. And it's a lot of heartbreaking and hard work.

After the success of the thing that we did in March — that 12-minute revue thing — I'll be honest with you. For 12 minutes that was like going through damn near, and I'm not even using hyperbolic statements by saying, coming out within an inch of my life.

When that moment was literally over and I was on the airplane landing back in New York, two of my teeth fell out. That's the level of stress I was [under]. Imagine landing in JFK and I got to rush to "The Tonight Show," but then it's like, Oh, wait, what's happening? Oh God, no! My teeth are falling out! And going to emergency surgery. My whole takeaway was like: Never again.

So of course when they hit me in July, "Hey, remember that 12 minute thing you did? You want to do the two-hour version of it?" I was like, "Hell no." And of course I hell noed for three weeks and it's like, "All right, I'll do it, but I'll just be a name on it. I ain't doing nothing." And then it went from that to like, "All right, what do you need me to do?"

What I will say is it's a two-hour show in which you got to figure out how to tell [the story of] hip-hop's 50-year totality — its origins, its peak period, its first moments of breaking new ground, the moment it went global around the world. You got to figure out a way to tell this story in two-hour interstitials and be all-inclusive.

It was just as stressful, even up until four hours ago. I'll just basically say that my teeth didn't fall out, thank God. And it was worth everything, because it's really a beautiful moment.

Sorry for that 12-hour answer, but that's just how my life rolls.

It was a great answer. What was your specific role behind the scenes?

Oh, I'm a producer. Jesse Collins called a group of us in to help facilitate: me, LL [Cool J], Fatima Robinson, Dionne Harmon, Brittany Brazil. There's a group of nine of us who were producers.

So, [part of] my actual division of labor thing was finding people to help facilitate music. This is a genre in which maybe the first six years of the art form, there was no such thing as an instrumental. "Or, "Hey, J.Period, can you recreate 'Check Out My Melody' by Eric B. & Rakim with no vocals in it?"

Finding the right people to do the music, sometimes I'd have to do it myself. And a lot of people in hip-hop have been super burnt. Super burnt. And I mean, that's putting it lightly.

And so you're giving these impassioned, Jerry Maguire, help-me-help-you speeches. The amount of times I was like, "Look, I really want you to reconsider your answer. This is our legacy we're talking about."

I'm using terms that a lot of these people, frankly, are hearing for the first time, Because like I've said in past interviews, hip-hop started as outlaw music. No one thought it was going to be a thing. So there's a whole generation that had to lay out the red carpet, just so that the next generation could benefit from it while we disposed of them.

But then that next generation gets disposed of, and then here comes my generation. And then the next thing, you wake up and it's like, "Oh, we're not relevant anymore," and dah, dah, dah.

And I'm trying to convince people, "Wait, you don't understand. Now we have a seat at the table. Now we get to control. All that we talked about, we need to control our destiny, and this is our culture." And there was a lot of that. And some people [were like], "All right, I'll do it for you." [To which I said,] "No, no, don't do it for me. Do it for the culture."

But then there were also people like, "Man, never again. F— all that." And there was also, "Hey, why wasn't I asked?" and all that stuff. So in these two hours, you're going to see eight to nine segments in which we try to wisely cover every base.

This is the "Lyricist" section, and this is the "Down South" section. And ["Ladies First"] is all about the ladies. And this is for those that passed away. And this is for the club bangers. And this is for music outside of America. And this is for the left-of-center alternative hip-hop.

Yes, we wanted to include everybody, but this is network television. And at that, you only get eight to 12 minutes at a time. So that's even hard. "Hey, why can't I do my chorus and my verse?" "Look, man, you got 32 seconds." If you've ever seen those "Tom and Jerry" cartoons where they're juggling plates in a kitchen — like 30 at a time — I don't recommend that to anybody.

But we got through it. I want everyone to feel proud of where hip-hop has come, because to be nine years old and to get on punishment for hip-hop — you know what I mean? I come from that generation. You've got to pay a price to live this culture.

And now it's established. So that's why I got involved. So there was a lot I had to do. A lot of calls, a lot of begging, a lot of arrangements, a lot of talking to people about clearing their samples, to call up publishing companies: "Look, it's just a four-second segment. It's just one drum roll. Can you please overlook it just for the sake of it?"

The amount of times I had to give those speeches. So yeah, that's what I had to do.

Jesus.

And that's just me. It's nine of us. So there's lighting directions, and choreography, and wardrobe, and dealing with clearance — like FCC, and, "They can't say that." And, "All right, which one of us is going to try to call Snoop to ask him that sort of thing?"

And the amount of Zooms that we were on at five in the morning in the Maldives or halfway around the world.

There must be some component of this process where you recognize that there could never be a perfect two-hour special. There could never be a perfect 200-hour special. There must be something freeing about realizing that nothing can be comprehensive when you're dealing with a cultural ocean like this.

[At one point], I had to take a hip-hop break. And the first thing that I did a week later, after recuperating, was I went on YouTube and I just watched every award show I remember watching — like prime Soul Train Awards back in '87, '88, '89, the years that Michael Jackson was killing the GRAMMYs.

Award shows were so magical to me, when I was a kid. There was a period just between five to maybe 15 or 16 in which I religiously watched that stuff, and you just take it for granted.

When Herbie Hancock did Rockit back in 1983 with all those mechanical break dancers, I wonder the work and the headaches that it took to make that happen. The drummer from Guns N' Roses [was] missing while they had to do "Patience" at the American Music Awards — and Don Henley, of all people, was just on the sidelines like, "Does anyone know how to drum?"

I was in the audience during the whole Chris Brown-Rihanna controversy of [2009]. I was literally at the GRAMMYs. There were like 40 minutes left, and I watched the producer run up the aisles.

Because the thing was, that was the year they decided, "You know what? This is going to be the first year in which we're going to ask artists to double down on stuff. So we're going to have Rihanna sing three songs, and we're going to have Chris do two songs. We're going to have Justin Timberlake. And then, suddenly, their absence now means that there's five major gaps open.

And they had 40 minutes left before they went to go live and I'm watching the producer make an announcement: "Ladies and gentlemen, something just happened. We can't get into it."

The level of viralness now on Instagram or Twitter is expected, but back then it was like, Oh, I wonder what happened? And they're just running up the aisles to Stevie Wonder, "Yo, can you [mimics rapid-fire, inaudible chatter]?"

And I'm looking at him, pondering: What the hell are they asking him? And then Stevie's getting up and doing it, and then, "Jonas Brothers, can you duh, duh, duh? Boyz II Men. Where's Al Green? Is Al Green here?" So literally, I'm watching them solve a headache in real time. And with 20 minutes left, backstage rehearsing, and we were really none the wiser.

I've seen that a few times. My very first GRAMMYs was when Luciano Pavarotti got sick and someone just randomly asked, "Hey, does anyone out there know the lyrics to 'Ave Maria'?" Aretha Franklin raised her hand, and we were all like, 'Wait, we mean the Italian version, like that 'Ave Maria.'" And she's like, "I do know the version."

We underestimated if Aretha Franklin from Detroit, Michigan knew how to sing something in Italian. And within a half hour she was on that stage and she killed that s—.

So it made me literally recapitulate every award show I ever watched.Now I'm watching with the analytical eye: I wonder what headaches it took to put that together? So, it changed me as a spectator and a participant.

I have a friend who's been a dedicated hip-hop fan his entire life. We were talking about the 50th anniversary of hip-hop. He questioned the entire enterprise, arguing that it's an arbitrary number that doesn't mean much to true rap fans. What does the 50th anniversary of hip-hop mean to you, personally?

Well, to me, it's important. There's an interlude that I put on the Things Fall Apart record. The album starts with an argument from [the 1990 film] Mo' Better Blues in which Denzel Washington and Wesley Snipes' jazz musician characters are arguing about just the disposability of the art form.

And it ends with a quote from Harry Allen saying that the thing about hip-hop is that most people think that it's disposable: Let me get what I can out this thing, and I'll throw them out the window. And on top of that, people don't even see it as art. And that really hit me in the gut, because I see the beauty of it.

This is kind of why I got into the game of: first it was with liner notes, and then with social media doing these mammoth history posts. And then it's like, Alright, well, let me write some books, because I'm afraid that no one's doing this level of critical thinking about this particular thing.

I know that the disdain and the dismissiveness that I got from some of hip-hop's participants does sort of stem from a place of ego being bruised. And it's righteous. It's righteous anger. But I also knew that if I sat on the sidelines, then it's like when I have grandkids and they Google this, and if it was a half-assed job, then that's my fault. And I definitely don't want to be the guy that talks, talks, complains, complains, without being a part of it.

So yeah, for the amount of people that prematurely died before the age of 30, and for the startling volume of people that have recently passed away in the last three years because of health issues, cardiac arrest, strokes, a lot of us are dying… You and I are talking right now, right when Norman Lear has passed away at the age of 101.

I just read that in The New York Times.

Dude, can you imagine "Tupac Shakur Dead at 103"? Can you imagine that for hip-hop?

It's a survival tool, because for a lot of us, that was the way out of poverty. It was vital for me. I couldn't just sit back and not watch one person behind the wheel. I have to be the designated driver. So, that's why it's important to celebrate that number.

And a big part of my convincing them was like when they were going to pass, like, "Nah, dog, I'm cool. I got a gig that night," I was like, "Dude, we're not going to do this for the 51st or the 52nd. And frankly, will we be here?" I will be 92 years old if it makes it to the 75th. You know what I mean?

The only person that got in my face was Latifah like, "Excuse me, I will be here for the 75th and I will be for the 100th. You don't know when I'm leaving." So I was like, "More power to you, Dana. All right, good. Queen Latifah will be here for the 100th."

What I'm gathering from what you're saying is that no matter what, it's important to have an organization of this prestige canonize this cultural force.

Oh, absolutely. And I know that oftentimes we play the game of public appearances for the gaze of the establishment. I don't want to get into that thing either: making performative celebrations just so that the mainstream can celebrate us.

I have to say that when you watch it, it really doesn't come off as compromised. This thing really looks good. That was the one thing that we laughed at in the group chat, like, "Man, we just went through Apocalypse Now, and are we all saying it was worth it?"

There are at least three people in my production thread that were sort of like, "Uh-huh, never again. I will never again subject myself." And one of them is dead serious. One of them started doing something the opposite, like, "Nah, I'm just doing classical music from now on. There's no stress there." But it was worth it. It was worth it to me.

*Questlove in 2023. Photo: Jamie McCarthy/Getty Images*

It looks to be a classy, expansive special. I'm excited for it to air.

The best part about it? So if you remember, to me, the star of the 12-minute version that we did at the GRAMMYs in March, was Jay-Z.

It was one of the things where it's like, "Hey, do we even ask Jay-Z?" And that's the one guy we decided ourselves, "Well, let's pass on him because number one, he's already performing with DJ Khaled, so we'll pass on him."

Jay-Z actually wound up being the star of that because he was a fan mouthing it in the audience, which to me was almost like better than us just doing a song with Jay-Z on stage. But the audience is the absolute star.

To see Chuck D smile — I've never seen Chuck D smile. As all these acts are coming out and Chuck D's like, singing [Sly and the Family Stone's] "Everyday People," like Boston fans sing "Sweet Caroline" at Red Sox games. Who knew that Chuck D was so jovial about things? But that's with everyone in the audience watching, supporting each other.

So that to me is also an important thing because as audience members on stage, they're ripping it, but as audience members, they're supporting each other. And that, I think is the most important part, because a lot of my take was like, "Wow, I didn't know that dah, dah, dah was so supportive." Or, "Man, Nelly actually knows every Public Enemy lyric. Who knew?" There are a lot of "Who knew?" moments that will shock people for this show.

I'm so glad you brought that up. That was one of my favorite moments during the Hip-Hop 50 performance at the 2022 GRAMMYs. Jay-Z is a billionaire twice over and a global cultural figure, but we see him in the audience, grinning ear-to-ear like a little boy, doing finger guns in the air.

He's getting his life back. And it's important. Especially now, I'm all about joy. And it's not even just like this particular hip-hop figure celebrating his music.

When Chance the Rapper comes out, again, I'm like, "Wow, [Cee] Knowledge from Digable Planets knows Chance?" And then I was like, "Well, they got kids, so of course I'm sure their kids play around the house." I'm doing all this analytical things like, "Wait, how do they know this song? And this is past their age range."

And that to me is the most telling part of this whole thing, to watch generational people get out of their actual zone and to find out that they're fans of — when GloRilla comes out, to watch [Digable Planets' Ladybug] Mecca mouth the lyrics. I was just like, "Oh, wow, OK."

That kind of puts to bed that stereotype that we only listen to the music in our realm. So, yeah, man — to me, that was the magic part of it all.

Credit: Paul Natkin/Getty Images

news

20 Iconic Hip-Hop Style Moments: From Run-D.M.C. To Runways

From Dapper Dan's iconic '80s creations to Kendrick Lamar's 2023 runway performance, hip-hop's influence and impact on style and fashion is undeniable. In honor of hip-hop's 50th anniversary, look back at the culture's enduring effect on fashion.

In the world of hip-hop, fashion is more than just clothing. It's a powerful means of self-expression, a cultural statement, and a reflection of the ever-evolving nature of the culture.

Since its origin in 1973, hip-hop has been synonymous with style — but the epochal music category known for breakbeats and lyrical flex also elevated, impacted, and revolutionized global fashion in a way no other genre ever has.

Real hip-hop heads know this. Before Cardi B was gracing the Met Gala in Mugler and award show red carpets in custom Schiaparelli, Dapper Dan was disassembling garment bags in his Harlem studio in the 1980s, tailoring legendary looks for rappers that would appear on famous album cover art. Crescendo moments like Kendrick Lamar’s performance at the Louis Vuitton Men’s Spring-Summer 2023 runway show in Paris in June 2022 didn’t happen without a storied trajectory toward the runway.

Big fashion moments in hip-hop have always captured the camera flash, but finding space to tell the bigger story of hip-hop’s connection and influence on fashion has not been without struggle. Journalist and author Sowmya Krishnamurphy said plenty of publishers passed on her anthology on the subject, Fashion Killa: How Hip-Hop Revolutionized High Fashion, and "the idea of hip hop fashion warranting 80,000 words."

"They didn't think it was big enough or culturally important," Krishnamurphy tells GRAMMY.com, "and of course, when I tell people that usually, the reaction is they're shocked."

Yet, at the 50 year anniversary, sands continue to shift swiftly. Last year exhibitions like the Fashion Institute of Technology’s Fresh, Fly, and Fabulous: Fifty Years of Hip-Hop Style popped up alongside notable publishing releases including journalist Vikki Tobak’s, Ice Cold. A Hip-Hop Jewelry Story. Tabak’s second published release covering hip-hop’s influence on style, following her 2018 title, Contact High: A Visual History of Hip-Hop.

"I wanted to go deeper into the history," Krishnamurphy continues. "The psychology, the sociology, all of these important factors that played a role in the rise of hip-hop and the rise of hip-hop fashion"

What do the next 50 years look like? "I would love to see a hip-hop brand, whether it be from an artist, a designer, creative director, somebody from the hip-hop space, become that next great American heritage brand," said Krishnamurphy.

In order to look forward we have to look back. In celebration of hip-hop’s 50 year legacy, GRAMMY.com examines iconic moments that have defined and inspired generations. From Tupac walking the runways at Versace to Gucci's inception-esque knockoff of Dapper Dan, these moments in hip-hop fashion showcase how artists have used clothing, jewelry, accessories, and personal style to shape the culture and leave an indelible mark on the world.

*The cover art to Eric B and Rakim’s* Paid in Full

Dapper Dan And Logomania: Luxury + High Fashion Streetwear

Dapper Dan, the legendary designer known as "the king of knock-offs," played a pivotal role in transforming luxury fashion into a symbol of empowerment and resistance for hip-hop stars, hustlers, and athletes starting in the 1980s. His Harlem boutique, famously open 24 hours a day, became a hub where high fashion collided with the grit of the streets.

Dapper Dan's customized, tailored outfits, crafted from deconstructed and transformed luxury items, often came with significantly higher price tags compared to ready-to-wear luxury fashion. A friend and favorite of artists like LL Cool J and Notorious B.I.G., Dapper Dan created iconic one-of-a-kind looks seen on artists like Eric B and Rakim’s on the cover of their Paid in Full album.

This fusion, marked by custom pieces emblazoned with designer logos, continues to influence hip-hop high fashion streetwear. His story — which began with endless raids by luxury houses like Fendi, who claimed copyright infringement — would come full circle with brands like Gucci later paying homage to his legacy.

Athleisure Takes Over

Hip-hop's intersection with sportswear gave rise to the "athleisure" trend in the 1980s and '90s, making tracksuits, sweatshirts, and sneakers everyday attire. This transformation was propelled by iconic figures such as Run-D.M.C. and their association with Adidas, as seen in photoshoots and music videos for tracks like "My Adidas."

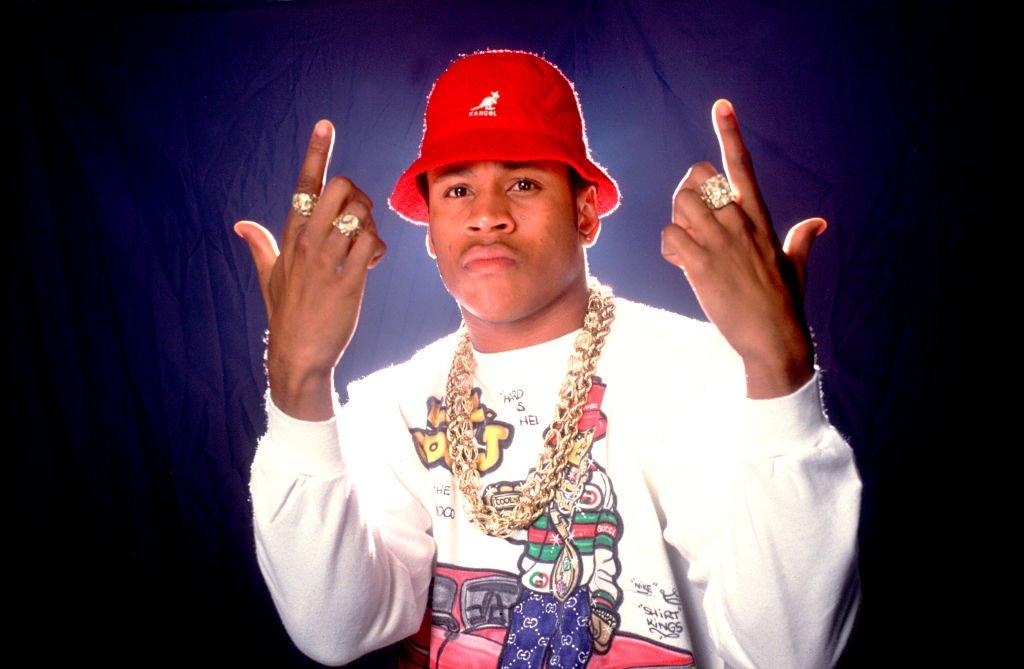

*LL Cool J. Photo: Paul Natkin/Getty Images*

LL Cool J’s Kangol Hat

The Kangol hat holds a prominent place in hip-hop fashion, often associated with the genre's early days in the '80s and '90s. This popular headwear became a symbol of casual coolness, popularized by hip-hop pioneers like LL Cool J and Run-D.M.C. The simple, round shape and the Kangaroo logo on the front became instantly recognizable, making the Kangol an essential accessory that was synonymous with a laid-back, streetwise style.

*Dr. Dre, comedian T.K. Kirkland, Eazy-E, and Too Short in 1989. Photo: Raymond Boyd/Getty Images*

N.W.A & Sports Team Representation

Hip-hop, and notably N.W.A., played a significant role in popularizing sports team representation in fashion. The Los Angeles Raiders' gear became synonymous with West Coast hip-hop thanks to its association with the group's members Dr. Dre, Eazy-E, and Ice Cube, as well as MC Ren.

*Slick Rick in 1991. Photo: Al Pereira/Getty Images/Michael Ochs Archives*

Slick Rick’s Rings & Gold Chains

Slick Rick "The Ruler" has made a lasting impact on hip-hop jewelry and fashion with his kingly display of jewelry and wealth. His trendsetting signature look — a fistful of gold rings and a neck heavily layered with an array of opulent chains — exuded a sense of grandeur and self-confidence. Slick Rick's bold and flamboyant approach to jewelry and fashion remains a defining element of hip-hop's sartorial history, well documented in Tobak's Ice Cold.

Tupac Walks The Versace Runway Show

Tupac Shakur's runway appearance at the 1996 Versace runway show was a remarkable and unexpected moment in fashion history. The show was part of Milan Fashion Week, and Versace was known for pushing boundaries and embracing popular culture in their designs. In Fashion Killa, Krishnamurpy documents Shakur's introduction to Gianni Versace and his participation in the 1996 Milan runway show, where he walked arm-in-arm with Kadida Jones.

*TLC. Photo: Tim Roney/Getty Images*

Women Embrace Oversized Styles

Oversized styles during the 1990s were not limited to menswear; many women in hip-hop during this time adopted a "tomboy" aesthetic. This trend was exemplified by artists like Aaliyah’s predilection for crop tops paired with oversized pants and outerwear (and iconic outfits like her well-remembered Tommy Hilfiger look.)

Many other female artists donned oversized, menswear-inspired looks, including TLC and their known love for matching outfits featuring baggy overalls, denim, and peeking boxer shorts and Missy Elliott's famous "trash bag" suit worn in her 1997 music video for "The Rain." Speaking to Elle Magazine two decades after the original video release Elliot told the magazine that it was a powerful symbol that helped mask her shyness, "I loved the idea of feeling like a hip hop Michelin woman."

Diddy Launches Sean John

Sean "Diddy" Combs’ launch of Sean John in 1998 was about more than just clothing. Following the success of other successful sportswear brands by music industry legends like Russell Simmons’ Phat Farm, Sean John further represented a lifestyle and a cultural movement. Inspired by his own fashion sensibilities, Diddy wanted to create elevated clothing that reflected the style and swagger of hip-hop. From tailored suits to sportswear, the brand was known for its bold designs and signature logo, and shared space with other successful brands like Jay-Z’s Rocawear and model Kimora Lee Simmons' brand Baby Phat.

*Lil' Kim. Photo: Ron Galella/Ron Galella Collection via Getty Images*

Lil’ Kim Steals The Show

Lil' Kim’s daring and iconic styles found a kindred home at Versace with

In 1999, Lil' Kim made waves at the MTV Video Music Awards with her unforgettable appearance in a lavender jumpsuit designed by Donatella Versace. This iconic moment solidified her close relationship with the fashion designer, and their collaboration played a pivotal role in reshaping the landscape of hip-hop fashion, pushing boundaries and embracing bold, daring styles predating other newsworthy moments like J.Lo’s 2000 appearance in "The Dress" at the GRAMMY Awards.

Lil Wayne Popularizes "Bling Bling"

Juvenile & Lil Wayne's "Bling Bling" marked a culturally significant moment. Coined in the late 1990s by Cash Money Records, the term "bling bling" became synonymous with the excessive and flashy display of luxury jewelry. Lil Wayne and the wider Cash Money roster celebrated this opulent aesthetic, solidifying the link between hip-hop music and lavish jewelry. As a result, "bling" became a cornerstone of hip-hop's visual identity.

Jay-Z x Nike Air Force 1

In 2004, Jay-Z's partnership with Nike produced the iconic "Roc-A-Fella" Air Force 1 sneakers, a significant collaboration that helped bridge the worlds of hip-hop and sneaker culture. These limited-edition kicks in white and blue colorways featured the Roc-A-Fella Records logo on the heel and were highly coveted by fans. The collaboration exemplified how hip-hop artists could have a profound impact on sneaker culture and streetwear by putting a unique spin on classic designs. Hova's design lives on in limitless references to fresh white Nike kicks.

Daft Punk and Pharrell Williams. Photo: Mark Davis/WireImage

Pharrell Williams' Hat At The 2014 GRAMMYs

Pharrell Williams made a memorable red carpet appearance at the 2014 GRAMMY Awards in a distinctive and oversized brown hat. Designed by Vivienne Westwood, the hat quickly became the talk of the event and social media. A perfect blend of sartorial daring, Pharrell's hat complemented his red Adidas track jacket while accentuating his unique sense of style. An instant fashion moment, the look sparked innumerable memes and, likely, a renewed interest in headwear.

Kanye’s Rise & Fall At Adidas (2013-2022)

Much more than a "moment," the rise and eventual fall of Kanye’s relationship with Adidas, was as documented in a recent investigation by the New York Times. The story begins in 2013 when West and the German sportswear brand agreed to enter a partnership. The collaboration would sell billions of dollars worth of shoes, known as "Yeezys," until West’s anti-semitic, misogynistic, fat-phobic, and other problematic public comments forced the Adidas brand to break from the partnership amid public outrage.

Supreme Drops x Hip-Hop Greats

Supreme, with its limited drops, bold designs, and collaborations with artists like Nas and Wu-Tang Clan, stands as a modern embodiment of hip-hop's influence on streetwear. The brand's ability to create hype, long lines outside its stores, and exclusive artist partnerships underscores the enduring synergy between hip-hop and street fashion.

*A model walks the runway at the Gucci Cruise 2018 show. Photo: Pietro D'Aprano/Getty Images*

Gucci Pays "homage" to Dapper Dan

When Gucci released a collection in 2017 that seemingly copied Dapper Dan's distinctive style, (particularly one look that seemed to be a direct re-make of a jacket he had created for Olympian Dionne Dixon in the '80s), it triggered outrage and accusations of cultural theft. This incident sparked a conversation about the fashion industry's tendency to co-opt urban and streetwear styles without proper recognition, while also displaying flagrant symbols of racism through designs.

Eventually, spurred by public outrage, the controversy led to a collaboration between Gucci and Dapper Dan, a significant moment in luxury fashion's acknowledgement and celebration of the contributions of Black culture, including streetwear and hip-hop to high fashion. "Had Twitter not spotted the, "Diane Dixon" [jacket] walking down the Gucci runway and then amplified that conversation on social media... I don't think we would have had this incredible comeback," Sowmya Krishnamurphy says.

A$AP Rocky x DIOR

Self-proclaimed "Fashion Killa" A$AP Rocky is a true fashion aficionado. In 2016, the sartorially obsessed musician and rapper became one of the faces of Dior Homme’s fall/winter campaign shot by photographer Willy Vanderperre — an early example of Rocky's many high fashion collaborations with the luxury European brand.

A$AP Rocky's tailored style and impeccable taste for high fashion labels was eloquently enumerated in the track "Fashion Killa" from his 2013 debut album Long. Live. ASAP, which namedrops some 36 luxury fashion brands. The music video for "Fashion Killa" was co-directed by Virgil Abloh featuring a Supreme jersey-clad Fenty founder, Rihanna long before the two became one of music’s most powerful couples. The track became an anthem for hip-hop’s appreciation for high fashion (and serves as the title for Krishnamurphy’s recently published anthology).

*Cardi B. Photo: Steve Granitz/WireImage*

Cardi B Wears Vintage Mugler At The 2019 GRAMMYs

Cardi B has solidified her "it girl" fashion status in 2018 and 2019 with bold and captivating style choices and designer collaborations that consistently turn heads. Her 2019 GRAMMYs red carpet appearance in exaggerated vintage Mugler gown, and many custom couture Met Gala looks by designers including Jeremy Scott and Thom Browne that showcased her penchant for drama and extravagance.

But Cardi B's fashion influence extends beyond her penchant for custom high-end designer pieces (like her 2021 gold-masked Schiaparelli look, one of nine looks in an evening.) Her unique ability to blend couture glamour with urban chic (she's known for championing emerging designers and streetwear brands) fosters a sense of inclusivity and diversity, and makes her a true trendsetter.

Beyoncé & Jay-Z in Tiffany & Co.’s "About Love" campaign

The power duo graced Tiffany & Co.'s "About Love'' campaign in 2021, showcasing the iconic "Tiffany Yellow Diamond," a 128.54-carat yellow worn by Beyoncé alongside a tuxedo-clad Jay-Z. The campaign sparked controversy in several ways, with some viewers unable to reconcile the use of such a prominent and historically significant diamond, sourced at the hands of slavery, in a campaign that could be seen as commercializing and diluting the diamond's cultural and historical importance. Despite mixed reaction to the campaign, their stunning appearance celebrated love, adorned with Tiffany jewels and reinforced their status as a power couple in both music and fashion.

Kendrick Lamar Performs At Louis Vuitton

When Kendrick Lamar performed live at the Louis Vuitton Men’s spring-summer 2023 runway show in Paris in June 2022 following the passing of Louis Vuitton’s beloved creative director Virgil Abloh, he underscored the inextricable connection between music, fashion and Black American culture.

Lamar sat front row next to Naomi Campbell, adorned with a jeweled crown of thorns made from diamonds and white gold worth over $2 million, while he performed tracks including "Savior," "N95," and "Rich Spirit'' from his last album, Mr. Morale and the Big Steppers before ending with a repeated mantra, "Long live Virgil." A giant children’s toy racetrack erected in the Cour Carrée of the Louvre became a yellow brick road where models marched, clad in designer looks with bold, streetwear-inspired design details, some strapped with oversized wearable stereo systems.

Pharrell Succeeds Virgil Abloh At Louis Vuitton

Pharrell Williams' appointment as the creative director at Louis Vuitton for their men's wear division in 2023 emphasized hip-hop's enduring influence on global fashion. Pharrell succeeded Virgil Abloh, who was the first Black American to hold the position.

Pharrell's path to this prestigious role, marked by his 2004 and 2008 collaborations with Louis Vuitton, as well as the founding of his streetwear label Billionaire Boy’s Club in 2006 alongside Nigo, the founder of BAPE and Kenzo's current artistic director, highlights the growing diversity and acknowledgment of Black talent within high fashion.