Photo courtesy of Fotografiska

list

10 Must-See Exhibitions And Activations Celebrating The 50th Anniversary Of Hip-Hop

In honor of hip-hop’s golden anniversary, check out 10 must-see exhibits, activations and programs that celebrate the history and enduring legacy of the boundary-pushing genre.

On Aug. 11, 1973, Clive Campbell, an 18-year-old performer known by the stage name DJ Kool Herc, and his sister Cindy co-organized a school fundraiser that became widely credited as the birthplace of hip-hop. From that Bronx apartment building community room emerged a wide-reaching movement that not only changed the lives of the artists who helped the genre evolve, but the lives of fans who summarily immersed themselves in the sound and culture of hip-hop.

Fifty years later, hip-hop has weaved itself into the cultural fabric of the world. Elements of the genre can be found throughout fashion, film, photography, dance, technology, language and art. Beyond its cultural impact, hip-hop serves as a platform for artists to highlight social concerns, such as discrimination, mental health issues, police brutality, and the inequalities that marginalized communities face. And by speaking truth to power, countless emcees and music makers have given a voice to the voiceless through their art.

Celebrations surrounding the golden anniversary of hip-hop have been going on throughout 2023, though many will ramp up this summer to coincide with the 50th anniversary of Kool Herc and Cindy's original Bronx jam. Here are 10 exhibitions, events and activations that celebrate the artistry, history, impact and evolution of the cultural movement.

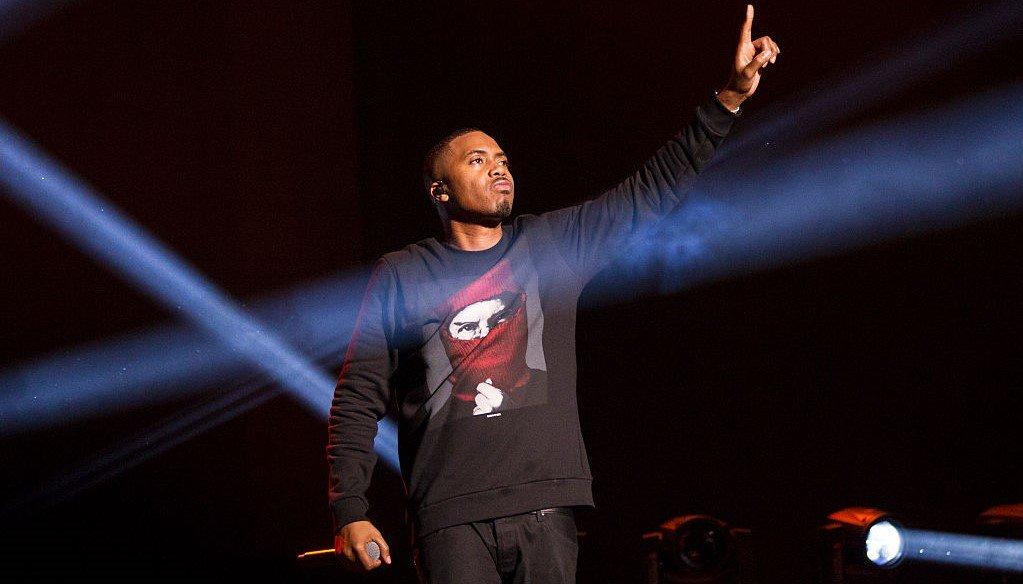

"Hip-Hop: Conscious, Unconscious"

Through May 20

Nas’ Mass Appeal Records has partnered with Fotografiska New York for a hip-hop photography exhibition that explores four of the genre’s core elements: rapping, DJing, breakdancing and graffiti.

Featuring 200 portraits, "Conscious, Unconscious" takes visitors through five decades of hip-hop (1972–2022), highlighting little-known connections between different artists and offering a closer look at pioneering women emcees, the various subcultures that arose across the country, and the gender disparities that exist within the male-dominated industry.

"We made a thoughtful effort to have the presence of women accurately represented, not overtly singling them out in any way," exhibit Co-Curator Sacha Jenkins said in a statement. "You’ll turn a corner and there will be a stunning portrait of Eve or a rare and intimate shot of Lil’ Kim that most visitors won’t have seen before."

40th Anniversary Screening Of Wild Style

June 11

From Breaking to Belly and Eight Mile, hip-hop cinema has helped extend the genre’s global reach by fusing sound with entertaining narratives that allow viewers to immerse themselves in the culture. To commemorate the 40th anniversary of Wild Style — the first hip-hop motion picture — the National Hip-Hop Museum will hold a screening at Zero Space NYC on June 11 in conjunction with Five Points Fest.

Director Charlie Ahearn and cast members will attend the event, which will also feature DJ sets and live graffiti painting.

"The Culture: Hip Hop and Contemporary Art in the 21st Century"

Through July 16

Mobile technology and the emergence of social media in the aughts helped bring hip-hop to the world, further cementing it as a major cultural influence. The Baltimore Museum of Art's "The Culture" exhibit explores the intersection between art, fashion, technology, and music over the past 20 years.

The exhibit features paintings, sculptures, fashion, music videos and memorabilia, including the Vivienne Westwood buffalo hat Pharrell donned for the 2014 GRAMMYs and one of Virgil Abloh’s last collaborations with Louis Vuitton.

"Rhythm, Bass and Place: Through the Lens"

Through June 24

This five-month-long series curated by Lynnée Denise explores the connectivity of Black music, tracking the African diaspora through performances, screenings, and curated conversations on themes like kinship, sacred traditions, Afrofuturism, literature and liberation.

At Harlem's Caribbean Cultural Center African Diaspora Institute, visitors can take a walk down memory lane at the "Through the Lens" exhibition, which explores different elements of Black music. Black-and-white photos captured by documentarians Joe Conzo Jr. showcase hip-hop and Latin music in New York in the 1970s and '80s, while Malik Yusef Cumbo's portraits feature the likes of Snoop Dogg and reggae singer Dawn Penn.

"[R]Evolution of Hip Hop"

Through June 30

At a pop-up in the Bronx for the forthcoming Universal Hip-Hop Museum, visitors can take an interactive trip through hip-hop’s golden era — 1986–1990 — in an exhibit focusing on the five pillars of the cultural movement: MCng, DJing, breakdancing, aerosol art, and knowledge. The exhibition includes original artwork, a giant interactive boombox, platinum plaques, sneakers, all-access passes, fliers, posters, recording equipment, Adidas sweatsuits worn by Run DMC, and a notepad with original lyrics from beatboxing pioneer Biz Markie and more.

"We’re providing visitors with a sneak preview of what we’re doing with the museum that opens in 2024," Rocky Bucano, president of the UHMM, told Billboard. "And for me personally, the responsibility of making sure that we have a space to amplify and magnify and inform people all around the world about what hip-hop actually is, is so important."

KRS-One’s "Birthplace of Hip-Hop" Initiative

Aug. 11 - TBD

Prolific emcee and preservationist KRS-One is marking the golden anniversary by hosting a series of events at the birthplace of hip-hop: the community center at 1520 Sedgwick Avenue in the Bronx, where DJ Kool Herc held the fundraiser that would spawn one of the most impactful cultural movements of the last century.

"The 50th Anniversary of Hip Hop is a global movement that speaks to the grit, voice, and power of how it came to be in the first place — we used our voices when they tried to silence us. We used our creativity when they tried to stifle us. We created the culture because we wanted to stand out and stand up for our artistry," the rapper said in a statement. "Hip Hop is the people’s movement. I am excited to showcase this to the world in the space where it all began at 1520 Sedgwick in the Community Center. It feels right to be here, where it all began."

Upcoming events include educational and historical programs, photo exhibits, a logo-making competition and a series of Hip-Hop Kultural Specialist courses taught by KRS-One.

Second-Annual Hip-Hop Block Party

Aug. 12

In homage to the school fundraiser-turned-neighborhood block party that birthed the movement, the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington D.C. will host its second-annual hip-hop block party this summer.

"The origins of hip-hop and rap rest in community where people gathered together in basements, on street corners, neighborhood dance parties and community shows to tell the stories of the people and places that brought it to life in a language all its own," Dwandalyn Reece, associate director for curatorial affairs at NMAAHC, said in a statement about the 2022 event.

Attendees can enjoy live musical performances, immersive art, interactive graffiti and breakdancing activities, and an outdoor exhibition of hip-hop artifacts. And it wouldn’t be an epic summer party without good eats: The museum’s Club Café will be cooking up a hip-hop-inspired menu to mark the occasion.

Last year’s inaugural celebration featured dance workshops, a panel discussion with hip-hop trailblazers Bun B, Roxanne Shanté, and Chuck D, performances from J.Period, D Smoke, DJ Heat and The Halluci Nation and a late-night dance party with a live set from Salt-n-Pepa’s DJ Spinderella.

"Contact High: A Visual History of Hip-Hop"

Through Jan. 7, 2024

Seattle’s Museum of Pop Culture’s "Contact High" exhibit highlights hip-hop’s vibrant aesthetic, showcasing more than 170 images from the genre’s 50-year history.

With photos dating back to the ‘70s, there’s a little something for everyone to enjoy, but ‘90s hip-hop and R&B fans in particular, will love this collection. Among the exhibit's images are never-before-seen contact sheets and photos of the genre’s biggest stars like Aaliyah, Wu-Tang Clan, Notorious B.I.G., Diddy, Tupac Shakur, Beastie Boys and more.

"From the Feet Up: 50 Years of Sneaks & Beats"

Ongoing

Run-DMC helped bring street style to the mainstream with their 1986 ode to Adidas, and sneakers have since become interlinked with the genre and its artists — from Eazy E’s love for Nike Cortez to Nelly’s "Air Forces Ones." This immersive exhibition at Mana Contemporary in Jersey City, New Jersey chronicles hip-hop’s long-running relationship with sneakers and how notable emcees helped propel different brands to commercial success.

Curated by avid sneaker collector Sean Williams, "From the Feet Up" features 50 sneakers designed and worn by various artists, including Public Enemy’s "Fear of a Black Planet" Pumas, De La Soul’s collab with Nike, as well as kicks worn by Beyoncé, Tupac and more. Visitors can also view the 2015 sneaker-culture documentary Laced Up in the backroom gallery after checking out the exhibit.

"The Message: The Revolutionary Power of Hip-Hop"

Ongoing

Nashville’s National Museum of African American Music will celebrate the culture all year long with an interactive exhibit that examines the origins of hip-hop, how music makers used technology, like sampling, to evolve the sound as well as the socio-political messages that many artists incorporated into their lyrics.

Visitors also get the chance to create their own custom beats inside the exhibit as they learn about the genre's pioneers.

Photo: Oscar Sánchez Photography

news

The Unending Evolution Of The Mixtape: "Without Mixtapes, There Would Be No Hip-Hop"

Today, the mixtape holds a variety of meanings — from a curated playlist to a non-label hip-hop release. From the dawn of the cassette to the internet-based culture of mixtape-making, musicians in hip-hop have developed their style via this format.

"Living in the Bronx, we got to hear all the latest music. If a party was on a Friday or a Saturday, by Monday the mixtapes would already be in my neighborhood," Paradise Gray says, beaming.

Now the chief curator and advisor for the soon-to-open Universal Hip Hop Museum in the Bronx — not to mention the co-host of the A&E TV show "Hip-Hop Relics," which follows the quest for genre relics alongside the likes of LL Cool J and Ice T — Gray grew up consuming countless mixtapes from the likes of the L Brothers, Grandmaster Flash, and the Cold Crush Brothers.

"The amount of music and the way it was curated was incredible, and having it on tape was way more valuable than hearing it on the radio because the radio didn’t have a rewind button," he says with a laugh. While the general public may have moved onto other formats, those cassettes are making a comeback and mixtapes continue to pervade every aspect of pop culture — both in their musical impact and nostalgic glory.

Today, the mixtape holds a whole swath of meanings — from a curated playlist to a non-label hip-hop release. But back in the early ‘70s, kids like Gray raised on everything from Motown to Thelonious Monk, George Clinton to James Brown were blending their influences.

"The first tapes were used to record people at places like a park jam, a party, a community gathering," explains Regan Sommer McCoy, founder of the Mixtape Museum, a repository of physical tape collections, nostalgic storytelling, and more. "They were called party tapes then, and people would make copies to give out to friends that couldn’t be there, so they could hear if the DJ was hot or not."

As the form became more popular, DJs like Kid Capri or Brucie B would start recording their club sets as well. "The recordings would sometimes include the DJ shouting out people who were in the room — and if you were in Harlem, maybe there were a few drug dealers in the room who even paid for a shoutout," she adds with a laugh.

McCoy is a longtime devotee of the form and a music industry professional (including a stint as manager of hip-hop legends Clipse). And the more she explored, the more she affirmed that these early tapes are an unparalleled document of a moment in music history.

Gray remembers making his own tapes as a young man in the late ‘70s, discovering the creativity that the new cassette technology could offer.

"We had two recorders, and we would keep the breaks extended even before we were conscious of what we were doing, sampling from cassette to cassette," he says. "We couldn’t afford turntables, but me and my childhood DJ partner, DJ Bob Rock, would make hip-hop practice tapes with the breakbeats and then put them on 8-track. We took over our neighborhood with those tapes because that’s what everybody had in their cars."

Zack Taylor, director of Cassette: A Documentary Mixtape, suggests that the freedom and control Gray felt were a driving force in the ubiquity of mixtapes during hip-hop's early days.

"By all accounts, the music industry in those days was doing everything it could to stifle hip-hop, to hold it back, label it as low-class output," he says. "But the mixtape represented creativity on a personal level. DJ Hollywood, Kool Herc, DJ Clue, these were people who didn’t have the support of a label or an infrastructure, but if they had $100 they could go buy a whole bunch of blank tapes, stay up late on Friday, and have the tapes ready on 125th Street in Harlem on Saturday morning with their blends.

And while some were relishing the individual creativity that cassettes could offer, others were enthused by the ability to listen to music in a more portable way, or merely thrilled by the opportunity to record their favorite songs off the radio. Within this space, talented musicians were finding their footing in a new landscape and developing signature styles.

"There was no such thing as hip-hop at the time — it was really the microcosm of the worldwide Afro-indigenous culture," Gray says. "It’s a sample of everything, not just the breakbeats." Artists were as free to indulge in snippets of Brahms as they were the Delfonics, stringing together their own mixes or making unique blends that would soundtrack an experience that was specific to their own.

Gray also notes that obsessives like the Bronx-based Tape Master would hit up various parties and clubs to document the moment and share the music, in turn allowing this self-defined movement to spread.

A big element of the tapes’ spread was a service called the OJs — a sort of proto-Uber where New Yorkers who owned expensive cars would offer them as a cab service. "If you were going to the club, at least once or twice you would want to show up in the OJ, a Cadillac or an Oldsmobile, and have them playing the hot new hip-hop tapes while they drove you around so everyone could see you and hear you," Gray says.

Listening to those mixtapes as a child, McCoy began to piece together the larger movement, the tapes acting as a sort of encyclopedia with something for everyone. "If I was interested in more R&B blends, I knew that someone like DJ Finesse from Queens would have R&B Blends volume 1 through a million," she explains. "And then I would go to camp every summer, and we would all bring our tapes and mix and swap them. There was a boy from California at camp and I’d get an entirely new sound."

"You couldn't get too hot…because then the RIAA is going to come in"

After first acting as a proving ground for talented DJs, mixtapes became intertwined with lyricists. Many prominent rappers — from Too Short to MC Hammer — started out by selling mixtapes of their work from the trunk of their car, showing up wherever they might find demand. DJs also started recording their sets in professional studios, toeing the line between commercial release and self-distribution — often based on whether there was enough demand to draw the industry’s attention. "You couldn’t get too hot, like DJ Drama, because then the RIAA is going to come in," McCoy says.

Eventually, these DJs would be hired on for entire projects with lyricists or even labels, uniting their voices in their unique blending style. "People like 50 Cent or Diddy would make tapes for their label," McCoy adds. Those artists would hire someone like DJ Whoo Kid to put together an entire tape with the label’s artists featured. "And then the big labels came in, and it got real messy."

Jehnie Burns, author of Mixtape Nostalgia: Culture, Memory, and Representation, argues that this move towards more structured recording processes ties back to the way hip-hop’s origins were separate from the mainstream — both by exclusion and intention.

“Mainstream releases would have to be worried about getting samples approved, making sure it was something that would sell, but hip-hop was often being made by people with something interesting to say that didn’t fit into that mold," Burns says. "It had a lot of similarities to the early days of punk — where local culture was so important, local community, local issues. Mixtapes are able to speak to that community in a way that they understand it and care about."

And when enough of a groundswell happens in a relatively new genre, some artists will work out ways to fit its ethos into the corporate music structure while others will continue to push in the indie world.

McCoy had first hand experience with that thin line while working with Clipse — an experience that proved foundational to the Mixtape Museum. At the time, the duo of Pusha T and No Malice had their contract transferred from Arista to Jive. When their work on Hell Hath No Fury began getting pushback, the duo attempted to get out of their obligation with their new label. "They were going to court with Jive and not able to drop their album, so they were like, ‘F— you, we’ll put out a mixtape,’" McCoy recalls. While label structures might mean trying to force Clipse into a certain box, the freedom of a mixtape meant they would be able to experiment and use their own musical language.

But when someone from the group’s camp dropped 10,000 copies of We Got It 4 Cheap, Vol. 1 (hosted by DJ Clinton Sparks) at McCoy’s Stuyvesant Town apartment, the realities of distributing a mixtape came to bear. Luckily, she had a helping hand in the form of Justo Faison — her then-boyfriend and the founder of the Annual Mixtape Awards. The annual awards honored innovative musicians pushing boundaries in the mixtape form, and Faison had fittingly amassed quite the collection of tapes, vinyl, and other early hip-hop memorabilia.

"I couldn't make a song, but because of the cassette, I could make an album"

After Faison passed in 2005, McCoy and a friend looked around his apartment, wondering what they could do to honor him. "I didn’t know what it meant yet, but I looked around the room and just said ‘Mixtape Museum,’" she remembers. And when she started working in academia, she continued pushing and researching, focused on adding emphasis to the artform that Faison had championed as well.

As the years have passed, countless people have felt that same endless nostalgic draw to the mixtape — as evidenced by the countless memoirs, novels, and films centered on the form. Everyone that made their own mixtape had a unique perspective, a unique purpose, and a yearning to make a document of it, something that would live on longer than a simple playlist.

"Making a mixtape was super empowering," Taylor says. "I couldn’t make a song, but because of the cassette, I could make an album."

Half a century on, the term "mixtape" remains relevant and meaningful. Even kids growing up today, post-8-track, post-cassette, post-CD, post-mp3 know what a mixtape is and the importance it can hold.

"Mixtape has become shorthand for this personal, eclectic collection," Burns says. "There’s a nostalgia factor because Gen X is coming to a certain age, a connection to a slower life less reliant on technology."

In hip-hop specifically, where the term continues to refer to a non-label or non-LP project, it continues to hold the meaning of a testing ground for experimentation and a connection to a niche community.

When Taylor set out in 2011 to make his documentary as an obituary to the mixtape, the Oxford English Dictionary had announced that they’d be removing the word cassette from their printed pages.

"To most people it was dead, but it was starting to have a real revival," he says. "If it were ever going to die, it would’ve happened already. But the portability and personalization will never be replaced." To this day, when shooting commercials, Taylor brings his tape deck (made by new French manufacturer We Are Rewind) and his pleather case of cassettes rather than sticking with a Spotify playlist.

"People are so much more excited to come up and talk about tapes, even from other sets," he says with a laugh. Burns similarly continues to see the advantages mixtapes hold over streaming — especially when it comes to the inability to skip around and the endless ability to rewind and start again. "You’re not skipping tracks or shuffling. You have to listen in the order that someone intentionally put it together," she says.

Perhaps it's that intentionality and experimentation that have allowed the mixtape to constantly evolve and stay relevant. Gray certainly sees it that way.

"Mixtapes are like time machines, musical magic," he says. "And every generation’s youth has the right to make it what they want it to be. Without mixtapes, there would be no hip-hop."

And while some older aficionados may be especially protective of the golden age of hip-hop, Gray sees the mixtape’s place as a living, breathing entity as essential to the genre’s development.

"The mixtape is one of the most invaluable tools that we have available because the internet is a cesspool and needs a filter," he says with a laugh. "Mixtape DJs are filters of culture and vibration. Back in the day, you knew to expect a certain level of quality with a tape from K Slay, Kid Capri, Red Alert, Chuck Chillout, Marley Marl. Today, you know that you’ve got some serious sounds coming out your speakers if it’s that kind of artist curating it."

Photo: Kimberly White/Getty Images for Hennessy

list

6 Must-Watch Hip-Hop Documentaries: 'Hip-Hop x Siempre,' 'My Mic Sounds Nice' & More...

Myriad documentaries have followed the journeys of hip-hop artists and unpacked the impact of hip-hop culture. In celebration of the genre's 50th anniversary, que up docs that shine a light on some of the biggest names and events in hip-hop history.

Given its social and cultural impact on our lives, it’s hard to believe that hip-hop is only celebrating its 50th anniversary this year. From its beginnings at a party in the Bronx, the culture of hip-hop bloomed and has spread to every corner of the globe.

Filmmakers have been commemorating hip-hop — from its MCs and DJs, to b-boys and girls and fashion icons — in all its glory for decades. Myriad documentaries follow the lives, journeys, successes and downfalls of hip-hop artists from across the U.S. and beyond. As we celebrate hip-hop’s birthday this August, here are five essential hip-hop documentaries to reflect on the magnitude of 50 years of groundbreaking culture.

Wild Style

Also considered the first ever hip-hop motion picture, Wild Style is so close to the truth that it’s more of a documentary. Offering a glimpse into 1981 New York, it stars real-life graffiti artists, musicians, rappers and dancers, portraying hip-hop as a cultural phenomenon alongside genres like punk and new wave.

Featuring some iconic names including Fab Five Freddy, Lady Pink, the Rock Steady Crew and the Cold Crush Brothers, the film’s vague plot doesn’t matter. Instead, Wild Style captures the essence and grit of New York City when hip-hop was on the precipice. It’s a hugely influential and inspirational part of the canon and a crucial historical document.

Hip-Hop Evolution

This four-part docuseries provides an overview of how hip-hop works and, as its name suggests, plots its evolution from emergence to global recognition. In making the film, MC Shad Kabango intended to explore how hip-hop made a name for itself in the music industry. Through the memories of stars like DJ Kool Herc himself, the Sugarhill Gang, Russell Simmons and Public Enemy, he discovers that the real legacy of hip-hop is how it allowed those without a voice to have their say.

Now four seasons in, this series covers every decade, style and corner of American hip-hop, highlighting the contributions of women like Queen Latifah and Monie Love. Charting key events from Kool Herc's first block party to the early 2020s, this multi-award-winning series is the perfect place to start if you want an overview of hip-hop's development from the perspective of the people who’ve led the way.

Nas: Time is ILLMatic

This 2014 documentary unpacks the events that led to Nas’ 1994 debut album ILLMatic. Through interviews with his father, brother and East Coast hip-hop legends like Pharrell, Alicia Keys and Busta Rhymes, it not only delves into the process of making the album, but of the social context in which he made it.

The artist said he made ILLMatic with the intention of showing people that hip-hop was changing and becoming something more real. "I tried to capture it like no one else could," he says.

The documentary’s producers came to make the film from a similar perspective. Co-Producer Erik Parker was writing for Vibe Magazine at the time of the album’s 10th anniversary and realized he couldn’t fit everything he wanted to say about it into a written article. He contacted One9 and together they decided to make this film.

Together, they ended up delving much deeper into the culture and wanted to reflect the feel of the streets that infuses the album itself. The result is a timeless and absorbing documentary that captures the real essence of the hip-hop scene.

My Mic Sounds Nice: A Truth About Women And Hip-Hop

Women are often left out of the conversation around hip-hop, despite their huge successes and significant contributions to the genre. This documentary by renowned filmmaker Ava DuVernay seeks to redress this by focusing on the careers of legends like Missy Elliot, Salt-N-Pepa, Eve, and MC Lyte.

Through interviews with these artists and and more, My Mic Sounds Nice offers a unique and insightful angle to the discourse around the issues women face in the industry — from sexual objectification to lower pay. With commentary from those who have dominated the rap and hip-hop world for decades but often haven't received the same accolades as their male counterparts, My Mic Sounds Nice is a must-see film.

The Art of Organized Noize

Focusing on a label rather than the artist, The Art of Organized Noize explores the pioneering producers behind the Dirty South sound. Organized Noize producers Rico Wade, Ray Murray and Sleepy Brown detail how Atlanta shaped the hip-hop world.

Record label Organized Noize was responsible for supporting the careers of Diddy, Outkast and L.A Reid amongst others — which it famously did from the confines of a dungeon. In a basement room, the Dungeon Family (OutKast, Goodie Mob, Organized Noize and a bunch of local artists) holed up, smoking weed and creating music that would define the region and popular hip-hop.

Organized Noize built an extraordinary sense of community and comradeship, which comes in interviews with some of its famed roster, as well as from admirers from further afield.

Hip-Hop x Siempre

Although historically left out of conversations about the genre, “Latinos have been an inherent part of hip-hop from its start," Rocio Guerrero, Head of Global Latin at Amazon Music, said in a statement. To wit, Amazon's documentary Hip-Hop x Siempre details the contributions of Latinx artists throughout the culture's 50-year run.

The Amazon Original includes interviews with Fat Joe, Cypress Hill's B-Real, N.O.R.E., and Residente, and up-and-coming acts such as Eladio Carrión, Villano Antillano, Myke Towers and Snow Tha Product.

"Latino artists take inspiration from Hip Hop beats and lyrics, infusing them with traditional Latin rhythms to make the genre our own, ultimately aiding in its global reach and relevance,” Guerrero continued, adding that the documentary honors "this shared history and its impact on our culture by highlighting the diverse and intergenerational voices that are part of the movement."

Photo: Jeremy Cowart

interview

Behind Ryan Tedder's Hits: Stories From The Studio With OneRepublic, Beyoncé, Taylor Swift & More

As OneRepublic releases their latest album, the group's frontman and pop maverick gives an inside look into some of the biggest songs he's written — from how Beyoncé operates to Tom Cruise's prediction for their 'Top Gun' smash.

Three months after OneRepublic began promoting their sixth album, Artificial Paradise, in February 2022, the band unexpectedly had their biggest release in nearly a decade. The pop-rock band's carefree jam, "I Ain't Worried," soundtracked Top Gun: Maverick's most memeable scene and quickly became a global smash — ultimately delaying album plans in favor of promoting their latest hit.

Two years later, "I Ain't Worried" is one of 16 tracks on Artificial Paradise, which arrived July 12. It's a seamless blend of songs that will resonate with longtime and newer fans alike. From the layered production of "Hurt," to the feel-good vibes of "Serotonin," to the evocative lyrics of "Last Holiday," Artificial Paradise shows that OneRepublic's sound is as dialed-in as it is ever-evolving.

The album also marks the end of an era for OneRepublic, as it's the last in their contract with Interscope Records. But for the group's singer, Ryan Tedder, that means the future is even more exciting than it's been in their entire 15-year career.

"I've never been more motivated to write the best material of my life than this very moment," he asserts. "I'm taking it as a challenge. We've had a lot of fun, and a lot of uplifting records for the last seven or eight years, but I also want to tap back into some deeper material with the band."

As he's been prepping Artificial Paradise with his OneRepublic cohorts, Tedder has also been as busy as he's ever been working with other artists. His career as a songwriter/producer took off almost simultaneously with OneRepublic's 2007 breakthrough, "Apologize" (his first major behind-the-board hit was Leona Lewis' "Bleeding Love"); to this day he's one of the go-to guys for pop's biggest names, from BLACKPINK to Tate McRae.

Tedder sat down with GRAMMY.com to share some of his most prominent memories of OneRepublic's biggest songs, as well as some of the hits he's written with Beyoncé, Adele, Taylor Swift and more.

OneRepublic — "Apologize," 'Dreaming Out Loud' (2007)

I was producing and writing other songs for different artists on Epic and Atlantic — I was just cutting my teeth as a songwriter in L.A. This is like 2004. I was at my lowest mentally and financially. I was completely broke. Creditors chasing me, literally dodging the taxman and getting my car repoed, everything.

I had that song in my back pocket for four years. A buddy of mine just reminded me last month, a songwriter from Nashville — Ashley Gorley, actually. We had a session last month, me, him and Amy Allen, and he brought it up. He was like, "Is it true, the story about 'Apologize'? You were completely broke living in L.A. and Epic Records offered you like 100 grand or something just for the right to record the song on one of their artists?"

And that is true. It was, like, 20 [grand], then 50, then 100. And I was salivating. I was, like, I need this money so bad. And I give so many songs to other people, but with that song, I drew a line in the sand and said, "No one will sing this song but me. I will die with this song."

It was my story, and I just didn't want anyone else to sing it. It was really that simple. It was a song about my past relationships, it was deeply personal. And it was also the song that — I spent two years trying to figure out what my sound was gonna be. I was a solo artist… and I wasn't landing on anything compelling. Then I landed on "Apologize" and a couple of other songs, and I was like, These songs make me think of a band, not solo artist material. So it was the song that led me to the sound of OneRepublic, and it also led me to the idea that I should start a band and not be a solo artist.

We do it every night. I'll never not do it. I've never gotten sick of it once. Every night that we do it, whether I'm in Houston or Hong Kong, I look out at the crowd and look at the band, and I'm like, Wow. This is the song that got us here.

Beyoncé — "Halo," 'I Am…Sacha Fierce' (2008)

We were halfway through promoting Dreaming Out Loud, our first album. I played basketball every day on tour, and I snapped my Achilles. The tour got canceled. The doctor told me not to even write. And I had this one sliver of an afternoon where my wife had to run an errand. And because I'm sadistic and crazy, I texted [songwriter] Evan Bogart, "I got a three-hour window, race over here. Beyoncé called me and asked me to write her a song. I want to do it with you." He had just come off his huge Rihanna No. 1, and we had an Ashley Tisdale single together.

When you write enough songs, not every day do the clouds part and God looks down on you and goes, "Here." But that's what happened on that day. I turn on the keyboard, the first sound that I play is the opening sound of the song. Sounds like angels singing. And we wrote the song pretty quick, as I recall.

I didn't get a response [from Beyoncé after sending "Halo" over], which I've now learned is very, very typical of her. I did Miley Cyrus and Beyoncé "II MOST WANTED" [from COWBOY CARTER] — I didn't know that was coming out 'til five days before it came out. And when I did "XO" [from 2013's Beyoncé], I found out that "XO" was coming out 12 hours before it came out. That's how she operates.

OneRepublic — "Good Life," 'Waking Up' (2009)

["Good Life"] was kind of a Hail Mary. We already knew that "All the Right Moves" would be the first single [from Waking Up]. We knew that "Secrets" was the second single. And in the 11th hour, our engineer at the time — who I ended up signing as a songwriter, Noel Zancanella — had this drum loop that he had made, and he played it for Brent [Kutzle] in our band. Brent said, "You gotta hear this drum loop that Noel made. It's incredible."

He played it for me the next morning, and I was like, "Yo throw some chords to this. I'm writing to this today." They threw some chords down, and the first thing out of my mouth was, [sings] "Oh, this has gotta be the good life."

It's the perfect example of, oftentimes, the chord I've tried to strike with this band with some of our bigger records, [which] is happy sad. Where you feel nostalgic and kind of melancholic, but at the same time, euphoric. That's what those chords and that melody did for me.

I was like, "Hey guys, would it be weird if I made the hook a whistle?" And everyone was like, "No! Do not whistle!" They're like, "Name the last hit song that had a whistle." And the only one I could think of was, like, Scorpion from like, 1988. [Laughs.] So I thought, To hell with it, man, it's been long enough, who cares? Let's try it. And the whistle kind of made the record. It became such a signature thing.

Adele — "Rumour Has It," '21' (2011)

"Rumour Has It" was the first song I did in probably a four year period, with any artist, that wasn't a ballad. All any artist ever wanted me to write with them or for them, was ballads, because of "Halo," and "Apologize" and "Bleeding Love."

I begged [Adele] to do a [song with] tempo, because we did "Turning Tables," another ballad. She was in a feisty mood [that day], so I was like, "Okay, we're doing a tempo today!"

Rick Rubin was originally producing the whole album. I was determined to produce Adele, not just write — because I wanted a shot to show her that I could, and to show myself. I stayed later after she left, and I remember thinking, What can I do in this record in this song that could be so difficult to reproduce that it might land me the gig?

So I intentionally muted the click track, changed the tempo, and [created that] whole piano bridge. I was making it up as I went. When she got in that morning. I said, "I have a crazy idea for a bridge. It's a movie." She listens and she says, "This is really different, I like this! How do we write to this?"

I mean, it was very difficult. [But] we finished the song. She recorded the entire song that day. She recorded the whole song in one take. I've never seen anyone do that in my life — before or since.

Then I didn't hear from her for six months. Because I handed over the files, and Rick Rubin's doing it, so I don't need to check on it. I randomly check on the status of the song — and at this point, if you're a songwriter or producer, you're assuming that they're not keeping the songs. Her manager emails my manager, "Hey, good news — she's keeping both songs they did, and she wants Ryan to finish 'Rumour Has It' production and mix it."

When I finally asked her, months later — probably at the GRAMMYs — I said, "Why didn't [Rick] do it?" She said, "Oh he did. It's that damn bridge! Nobody could figure out what the hell you were doing…It was so problematic that we just gave up on it."

OneRepublic — "Counting Stars," 'Native' (2013)

I was in a Beyoncé camp in the Hamptons writing for the self-titled album. [There were] a bunch of people in the house — me, Greg Kurstin, Sia — it was a fun group of people. I had four days there, and every morning I'd get up an hour and a half before I had to leave, make a coffee, and start prepping for the day. On the third day, I got up, I'm in the basement of this house at like 7 in the morning, and I'm coming up with ideas. I stumble across that chord progression, the guitar and the melody. It was instant shivers up my spine.

"Lately I've been losing sleep, dreaming about the things that we could be" is the only line that I had. [My] first thought was, I should play this for Beyoncé, and then I'm listening to it and going, This is not Beyoncé, not even remotely. It'd be a waste. So I tabled it, and I texted the guys in my band, "Hey, I think I have a potentially really big record. I'm going to finish it when I get back to Denver."

I got back the next week, started recording it, did four or five versions of the chorus, bouncing all the versions off my wife, and then eventually landed it. And when I played it for the band, they were like, "This is our favorite song."

Taylor Swift — "Welcome to New York," '1989' (2014)

It was my second session with Taylor. The first one was [1989's] "I Know Places," and she sent me a voice memo. I was looking for a house in Venice [California], because we were spending so much time in L.A. So that whole memory is attached to me migrating back to Los Angeles.

But I knew what she was talking about, because I lived in New York, and I remember the feeling — endless possibilities, all the different people and races and sexes and loves. That was her New York chapter. She was so excited to be there. If you never lived there, and especially if you get there and you've got a little money in the pocket, it is so exhilarating.

It was me just kind of witnessing her brilliant, fast-paced, lyrical wizardry. [Co-producer] Max [Martin] and I had a conversation nine months later at the GRAMMYs, when we had literally just won for 1989. He kind of laughed, he pointed to all the other producers on the album, and he's like, "If she had, like, three more hours in the day, she would just figure out what we do and she would do it. And she wouldn't need any of us."

And I still think that's true. Some people are just forces of nature in and among themselves, and she's one of them. She just blew me away. She's the most talented top liner I've ever been in a room with, bar none. If you're talking lyric and melody, I've never been in a room with anyone faster, more adept, knows more what they want to say, focused, efficient, and just talented.

Jonas Brothers — "Sucker," 'Happiness Begins' (2019)

I had gone through a pretty dry spell mentally, emotionally. I had just burned it at both ends and tapped out, call it end of 2016. So, really, all of 2017 for me was a blur and a wash. I did a bunch of sessions in the first three months of the year, and then I just couldn't get a song out. I kept having, song after song, artists telling me it's the first single, [then] the song was not even on the album. I had never experienced that in my career.

I went six to nine months without finishing a song, which for me is unheard of. Andrew Watt kind of roped me back into working with him. We did "Easier" for 5 Seconds of Summer, and we did some Sam Smith and some Miley Cyrus, and right in that same window, I did this song "Sucker." Two [or] three months later, Wendy Goldstein from Republic [Records] heard the record, I had sent it to her. She'd said, very quietly, "We're relaunching the Jonas Brothers. They want you to be involved in a major way. Do you have anything?"

She calls me, she goes, "Ryan, do not play this for anybody else. This is their comeback single. It's a No. 1 record. Watch what we're gonna do." And she delivered.

OneRepublic — "I Ain't Worried," 'Top Gun: Maverick' Soundtrack (2022)

My memory is, being in lockdown in COVID, and just being like, Who knows when this is going to end, working out of my Airstream at my house. I had done a lot of songs for movies over the years, and [for] that particular [song] Randy Spendlove, who runs [music at] Paramount, called me.

I end up Zooming with Tom Cruise [and Top Gun: Maverick director] Jerry Bruckheimer — everybody's in lockdown during post-production. The overarching memory was, Holy cow, I'm doing the scene, I'm doing the song for Top Gun. I can't believe this is happening. But the only way I knew how to approach it, rather than to, like, overreact and s— the bed, was, It's just another day.

I do prescription songs for movies, TV, film all the time. I love a brief. It's so antithetical to most writers. I'm either uncontrollably lazy or the most productive person you've ever met. And the dividing line between the two is, if I'm chasing some directive, some motivation, some endpoint, then I can be wildly productive.

I just thought, I'm going to do the absolute best thing I can do for this scene and serve the film. OneRepublic being the performing artist was not on the menu in my mind. I just told them, "I think you need a cool indie band sounding, like, breakbeat." I used adjectives to describe what I heard when I saw the scene, and Tom got really ramped and excited.

You could argue [it's the biggest song] since the band started. The thing about it is, it's kind of become one of those every summer [hits]. And when it blew up, that's what Tom said. He said, "Mark my words, dude. You're gonna have a hit with this every summer for, like, the next 20 years or more."

And that's what happened. The moment Memorial Day happened, "I Ain't Worried" got defrosted and marched itself back into the top 100.

Tate McRae — "Greedy," 'THINK LATER' (2023)

We had "10:35" [with Tiësto] the previous year that had been, like, a No. 1 in the UK and across Europe and Australia. So we were coming off the back of that, and the one thing she was clear about was, "That is not the direction of what I want to do."

If my memory serves me correct, "greedy" was the next to last session we had. Everything we had done up to that point was kind of dark, midtempo, emotional. So "greedy" was the weirdo outlier. I kept pushing her to do a dance record. I was like, "Tate, there's a lot of people that have great voices, and there's a lot of people who can write, but none of those people are professional dancers like you are. Your secret weapon is the thing you're not using. In this game and this career, you've got to use every asset that you have and exploit it."

There was a lot of cajoling. On that day, we did it, and I thought it was badass, and loved it. And she was like, "Ugh, what do we just do? What is this?"

So then it was just, like, months, months and months of me constantly bringing that song back up, and playing it for her, and annoying the s— out of her. And she came around on it.

She has very specific taste. So much of the music with Tate, it really is her steering. I'll do what I think is like a finished version of a song, and then she will push everyone for weeks, if not months, to extract every ounce of everything out of them, to push the song harder, further, edgier — 19 versions of a song, until finally she goes, "Okay, this is the one." She's a perfectionist.

OneRepublic — "Last Holiday," 'Artificial Paradise' (2024)

I love [our latest single] "Hurt," but my favorite song on the album is called "Last Holiday." I probably started the beginning of that lyric, I'm not joking, seven, eight years ago. But I didn't finish it 'til this past year.

The verses are little maxims and words of advice that I've been given throughout the years. It's almost cynical in a way, the song. When I wrote the chorus, I was definitely in kind of a down place. So the opening line is, "So I don't believe in the stars anymore/ They never gave me what I wished for." And it's, obviously, a very not-so-slight reference to "Counting Stars." But it's also hopeful — "We've got some problems, okay, but this isn't our last holiday."

It's very simple sentiments. Press pause. Take some moments. Find God before it all ends. All these things with this big, soaring chorus. Musically and emotionally and sonically, that song — and "Hurt," for sure — but "Last Holiday" is extremely us-sounding.

The biggest enemy that we've had over the course of 18 years, I'll be the first to volunteer, is, this ever-evolving, undulating sound. No one's gonna accuse me of making these super complex concept albums, because that's just not how my brain's wired. I grew up listening to the radio. I didn't grow up hanging out in the Bowery in CBGBs listening to Nick Cave. So for us, the downside to that, and for me doing all these songs for all these other people, is the constant push and pull of "What is their sound? What genre is it?"

I couldn't put a pin in exactly what the sound is, but what I would say is, if you look at the last 18 years, a song like "Last Holiday" really encompasses, sonically, what this band is about. It's very moving, and emotional, and dynamic. It takes me to a place — that's the best way for me to put it. And hopefully the listener finds the same.

Latest News & Exclusive Videos

Behind Ryan Tedder's Hits: Stories From The Studio With OneRepublic, Beyoncé, Taylor Swift & More

Crowder Performs "Grave Robber"

NCT 127 Essential Songs: 15 Tracks You Need To Know From The K-Pop Juggernauts

5 Rising L.A. Rappers To Know: Jayson Cash, 310babii & More

Why Elliott Smith's 'Roman Candle' Is A Watershed For Lo-Fi Indie Folk

Photo courtesy of SM Entertainment

list

NCT 127 Essential Songs: 15 Tracks You Need To Know From The K-Pop Juggernauts

Eight years after their debut, NCT 127 have released their sixth studio album, 'WALK.' Before you dive in, press play on this chronological list of NCT 127 hits and deep cuts that show their musical ingenuity — from "Highway to Heaven" to "Pricey."

In the K-pop industry, the Neo Culture Technology juggernaut stands out as a cosmopolitan universe. The project is characterized by its highly experimental approach, where each of NCT's subgroups contribute a unique twist.

This is especially true of NCT 127. Comprised of Taeyong, Taeil, Jaehyun, Johnny, Yuta, Doyoung, Jungwoo, Mark, and Haechan, NCT 127's identity was forged via innovative arrangements that defy convention.

During their rookie days, this ahead-of-its-time strategy felt polarizing and raised a few eyebrows. However, after some years of ambivalence (and with some lineup changes in between), they exploded in popularity during the early pandemic with their second studio album, NCT #127: Neo Zone. This record gave them their first title as million sellers, significantly increasing their listeners globally — many of whom embraced the group's music as an escape during quarantine.

Read more: Breaking Down The NCT System, From The Rotational NCT U To The Upcoming NCT Tokyo

Today, they are more influential than ever and their sound is more accepted in the ever-expanidng scope of K-pop. Nonetheless, some K-pop listeners tend to pigeonhole the group as "noise," despite having a diverse catalog and some of the best vocalists of their generation.

Nearly coinciding with their eighth anniversary, NCT 127 released their sixth studio album, WALK on July 15. To mark this occasion, GRAMMY.com presents a song list — in chronological order — demonstrating their musical geniality, which extends far beyond the public's usual perception.

"Switch"

The group's first mini-album, NCT #127, laid the foundations of their audacious sound and paired it with vocal finesse. To wit, the lead single "Fire Truck" arrived as an unapologetic disruptor shaking up the K-pop industry.

But the bookends of the EP are uniquely contrasting. Whereas "Fire Truck" opens with bold posturing, the outlier "Switch" concludes the ride with a more lighthearted and youthful production. In a way, this song could also be considered a prelude to the NCT universe, as it was recorded a year before NCT 127's debut, and it features members of other NCT iterations — like WayV and Dream — when they were still trainees.

"Limitless"

The name of this track is a statement of the group's boundary-pushing ethos. True to form, the song is built over a hammering backbone and lengthy synths that bite. The chorus is the highlight; its dynamic explosion of vocals only intensifies the momentum. And while the Korean version is strong, it could be argued that the Japanese rendition imbues the song with new layers of depth that truly elevate it.

It’s worth mentioning that, during the Limitless era, Doyoung and Johnny were added to the lineup, marking NCT 127’s first release with nine members — a move consistent with the original (now-defunct) concept of the NCT system.

"Sun & Moon"

Some songs are crafted for faraway souls and to offer solace to the aching heart. That's why "Sun and Moon," an evocative B-side from NCT 127's third extended play, exists as an unmissable gem.

It's a lyrical tale of longing, where Taeil, Doyoung, Johnny, Taeyong, Jaehyun, and Yuta serenade a distant love, hoping the gap will shrink and a reunion will come. The arrangement is understated but dream-like, and when the pre-chorus arrives, the most beautiful lines are unveiled: "When my moon rises/ Your sun rises as well/ Under the same sky/ In this different time/ Our hearts are connected/ Under the same sky."

"Come Back"

Co-created by GRAMMY-nominated producer Mike Daley and multi-instrumentalist Mitchell Owens, "Come Back" exemplifies maximalism, undulating between intensity and elegance.

"One of the standout aspects of this song is the creative use of chops throughout the track," Daley tells GRAMMY.com. "Even though the arrangement follows a pretty standard structure for us, these chops add a unique flavor that sets 'Come Back' apart. We got to be more experimental [for this track] and bring in some unusual elements."

The voices of Taeil and Doyoung prominently take center stage, infusing potency that ensures smooth progressions throughout the production.

"Lips"

Featured on the group's first Japanese studio album, Awaken, "Lips" is an unjustly overlooked cut that blends sensuality with hypnotizing Latin rhythms. The deeper you are immersed in it, the more enchanting it becomes, casting a spell over your mind.

Its minimalist formula is effective, and the lyrics hint at a compelling journey: "Your lips come and take me to the place to go/ The place you would know where you should go." Sometimes, less is more, and the impact can be equally powerful.

"Highway to Heaven"

"Highway to Heaven" shines as one of the crown jewels in NCT 127's discography, praised not only for its cathartic production but also for marking a turnaround in their artistry. It sees them delving into more subdued and ethereal soundworlds.

A pre-release single from their fourth mini album, We Are Superhuman, the instrumental is woven with buzzy percussion and silken guitar strings. The group's vocal prowess truly exhilarates, crescendoing a declaration of freedom during the chorus: "We'll take the highway to heaven/ Any time, anywhere I feel you/ You and I, highway to heaven/ This place where we're together is heaven."

The track reaches its pinnacle with an interlude guided by Jungwoo's velvety delivery, eventually setting the stage for Haechan's soaring voice.

"Superhuman"

"Superhuman," the lead single from We Are Superhuman, is a timeless masterpiece. The avant garde song showcases the group's expansive adaptability, exchanging their usual edge for intricate sophistication.

American singer/songwriter Adrian Mckinnon — a frequent collaborator of SM Entertainment, home of the NCT project — teamed up with South Korean producers TAK and 1Take to bring the song to life, and he recalls being "blown away" when he listened to the instrumental. "All the glitches and stutters immediately gave nostalgia," Mckinnon tells GRAMMY.com, noting the sound choices reminded him of old school video games. "[The song] kind of sits in its own lane, maybe somewhere between glitch funk and glitch hop. Maybe a little Daft Punky too?"

Mckinnon says he sat with the instrumental track for half an hour before recording his vocal ideas. "I wanted to absorb it in its entirety before trying anything."

He also explains that they created the song without a specific group in mind, so he was excited to discover the song was placed with NCT 127. "I think this speaks to the versatile nature of the group because they executed the track very well and were able to make it their own. It's easily one of my favorite songs I've been a part of."

"Love Me Now"

Another piece from Daley and Owens, "Love Me Now" pulses with gentleness and heartwarming nostalgia. It's a song made for those days when everything feels right in place.

Daley recalled working on "Love Me Now" during a K-pop songwriting camp in Seoul, and says he refined an existing track. "Most of our stuff is tailor-made for artists in Korea, but this track was very much a U.S. pop/dance radio-sounding track," he says. "It doesn't feature a ton of sections, switch-ups, or the musically intricate bridge that a lot of our K-pop songs normally have. It's very minimalistic, bright, and centered, and sometimes that's all you need."

He observes the creation process of "Love Me Now" was more straightforward than "Come Back," as the latter contains the usual elaborateness of K-pop productions. "That simplicity in ['Love Me Now'] lent itself to making a very catchy, memorable record that was easy to digest."

"NonStop"

By NCT standards, "NonStop" — from the repackaged album NCT #127 Neo Zone: The Final Round — is a B-side that overflows with the potential of a lead single. It's an amalgam of unburdened rap verses and cohesive vocals that glide effortlessly across a cutting-edge production.

Adrian Mckinnon explains that he and Kenzie chose the track from a selection created by the British production duo LDN Noise due to the magnetic pull of the intro. "The arpeggiated tones and the crazy melody of the lead synth immediately took us to the future," he says. "The chord progression and the rising energy out of the pre-chorus — it all felt like some high-speed race through some futuristic city."

The development of the structure proved quite challenging, but the end result encapsulated the intended concept. "Listening to it in its final form, you would think the sections were obvious, but each of the melody and topline — including others that didn't make the song — all felt quite hooky," McKinnon shares. "But since you only have so much 'song,' you must pick your favorite bits and massage the ideas together. That's how we arrived at what 'NonStop' came to be."

"First Love"

A burgeoning romance transforms into the dulcet melodies that define "First Love," a B-side from NCT 127's second Japanese EP, Loveholic, released in February 2021. Excitement beams throughout the lines of the song, capturing the world of possibilities that come with finding the person you've always dreamed of.

When the group leans towards professing love in all its shapes, they do so with a rawness that percolates through their voices, easily perceptible to all. And here, they opt for a playful and tender side.

"Breakfast"

Off of their third full-length album, Sticker, "Breakfast" is distinguished by its harmonic richness and stunning vocal arrangements.\

The track emerged from a collaboration in which Swedish producer Simon Petrén devised the sonic framework, complemented by GRAMMY-winning songwriter Ninos Hanna and songwriter/producer Andreas Öberg. "As the melody ideas evolved, the song was also developed and built up to match the topline," Öberg tells GRAMMY.com. "The original demo was called 'Breakfast' and tailor-made for [the group]. SM Entertainment decided to release this song with them shortly after we submitted it."

Öberg describes the composition as "an interesting hybrid," with the original demo molded to be "a modern dance/house record while still using advanced chord progressions not only with influences from jazz and fusion."

He also cites Michael Jackson as an inspiration, drawing from "his unique style of switching between minor and major tonalities."

"Favorite (Vampire)"

After releasing Sticker, NCT 127 wasted no time and quickly followed up with a repackaged album centered around the hauntingly resonant "Favorite." A brainchild of Kenzie, American producer Rodney "Darkchild" Jerkins, and singer/songwriter Rodnae "Chikk" Bell, this record is the most tempered of all the NCT 127's title tracks.

A whistling sample introduces a thumping trap beat that rapidly unfolds into piercing lines — courtesy of Taeyong and Mark — that slice through the song. But as we hit the road toward the chorus, "Favorite" veers into a more vocally-driven approach, a splendid transition that balances its core. In classic SM style, the bridge is a triumph, with Doyoung, Taeil, and Haechan pouring their hearts out as if they've been shattered into a hundred pieces.

"Angel Eyes"

Listening to "Angel Eyes," a cut nestled in the middle of their most recent release, Fact Check, is akin to a healing escape. From the first seconds, pure bliss fills the air and quickly transforms into an open invitation to lose ourselves in the music.

"Paradise, like an angel fly/ With your wings, make me fly through the brilliant world/ My delight in all the days and nights/ Even in darkness, make me dream the greatest dream," they sing in the last chorus, prescribing optimism atop a layering reminiscent of the '80s.

"Pricey"

One of WALK's B-sides, "Pricey" boasts a delightful instrumental with thick basslines and a fusion of piano and guitar chords. Although the rapped chorus momentarily threatens to stall the pace, vibrant ad-libs — growing more captivating as the song progresses — quickly pick it back up, perfectly aligning the overall effort with their unique sound.

"Pricey" was originally intended for the American market, which makes it all the more inexplicable that it was tucked away in the NCT 127 vault for so long. Thankfully, it's now receiving the spotlight it deserves – it's simply too remarkable to remain unearthed.

More K-Pop News

NCT 127 Essential Songs: 15 Tracks You Need To Know From The K-Pop Juggernauts

ENHYPEN And JVKE "Say Yes" To Cross-Cultural Collabs & Exploring New Genres

GRAMMY Museum Partners With HYBE For New K-Pop Exhibit 'HYBE: We Believe In Music' Opening Aug. 2

K-Pop Group RIIZE Detail Every Track On New Compilation 'RIIZING – The 1st Mini Album'

The ABCDs Of Nayeon: How The TWICE Member Embraced Her Authenticity On ‘NA’