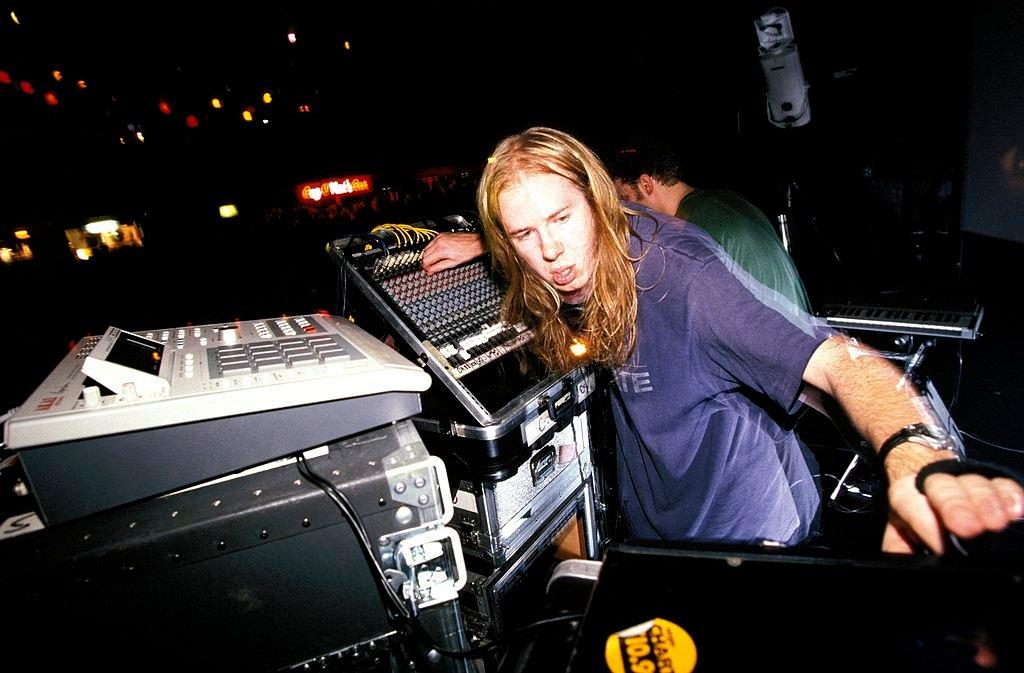

Photo: Mick Hutson/Redferns

The Chemical Brothers perform live in 1995

news

How 1995 Became The Year Dance Music Albums Came Of Age

In the mid-'90s, then-scrappy acts like The Chemical Brothers, Leftfield, Goldie and Aphex Twin released landmark albums, upending misconceptions about electronic music and setting the standard for a new dance generation

Back in 1995, years before the rise of Coachella, Lollapalooza was the U.S. festival to beat. Founded in 1991 by Jane's Addiction frontman Perry Farrell, the multi-city roadshow quickly became a peak summer institution.

Lollapalooza's 1995 lineup featured alt-rock royalty like Sonic Youth, Pavement and The Jesus Lizard alongside artists as diverse as Beck, Cypress Hill, Sinead O'Connor and Hole. For all its genre-hopping, though, the festival largely missed one sound close to its founder's heart: electronic music. Even Moby, the former punk and sole raver on the bill, turned up with a guitar and his best rock snarl.

Across the Atlantic, iconic U.K. festival Glastonbury took an alternative view on 1995: In its universe, electronic music was on the ascent. For the first time in Glastonbury's then-25-year history, the festival introduced a Dance Tent, which featured trip-hop collective Massive Attack alongside homegrown DJs Carl Cox, Spooky and Darren Emerson.

Elsewhere, from the main stage to the Jazz World stage, Glastonbury lined up the best and brightest of U.K.-made electronic music: The Prodigy, Portishead, Tricky, Goldie and Orbital among them. That June weekend, a musical movement coalesced on a farm in the English countryside.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed/svJvT6ruolA' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

One year prior, The Prodigy's Music For The Jilted Generation lit the fuse on the momentum to come. Released in July 1994, the album was an immediate outlier in a golden age of alternative rock. Soundgarden, Green Day, Pearl Jam and Nine Inch Nails loomed large Stateside, while in the U.K., Blur's Parklife and Oasis' Definitely Maybe battled for Britpop supremacy. Liam Howlett, The Prodigy's beatmaker-in-chief, came from a different world. Music For The Jilted Generation cut the grit and aggression of punk rock with the ecstatic highs of raving, producing indelible anthems like "Their Law" and "No Good (Start The Dance)." The album topped the charts in the U.K., but it failed to break through in the U.S.

By the next year, a varied cast of then-newcomers was ready to make its mark. Not all fit The Prodigy's fast and furious mold. The crop of albums released in 1995, including several remarkable debuts, showcased the many moods, textures and possibilities in electronic music. The year brought legitimacy and studio polish to the format, while also sparking an era of intense, analog-heavy live shows.

Released in January 1995, Leftfield's Leftism reached for a more transcendent plane than the rave anthems of the day. "At the time, a lot of people thought dance music was this fake thing," Neil Barnes, one half of the duo, alongside Paul Daley, told The Guardian in 2017. "[Leftism] came out in the middle of Britpop, which we didn't really understand."

Leftfield called on surprising voices, including Toni Halliday of alt-rock group Curve and The Sex Pistols frontman John Lydon, to challenge the demarcation of dance music. While the album was nominally "progressive house," its songs channeled the thrum of London through dub, reggae and pop hooks. Over two decades later, Leftism remains thrillingly true to its time and place.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed/CUgeEeEoFko' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Across the country from Liam Howlett's Essex studio, Bristol natives Massive Attack had their own designs on the jilted generation. Where The Prodigy raged, Massive Attack seethed. Like Leftfield's Leftism, Massive Attack's Blue Lines (1991) and Protection (1994) drew on dub, reggae and soul, arriving not at house music, but at the slow creep of Bristol's signature trip-hop sound. Protection collaborator Tricky broke through in 1995 with his own trip-hop masterpiece, Maxinquaye; its opener, "Overcome," is an alternative version of Protection cut "Karmacoma." Björk, a then-recent '90s transplant to the U.K. from Iceland, also called on Bristol connections for her startling second album, Post (1995).

Read: 'Post' at 25: How Björk Brought Her Ageless Sophomore Album To Life

Meanwhile, in London, motor-mouthed DJ/producer Goldie emerged from the basement clubs with a fully realized debut album. Released in July 1995, Timeless exemplified the drum & bass genre in LP form, stretching from deep and sonorous atmospherics to heads-down jungle roll-outs. Audacious to a fault, Goldie packaged his star-making single, "Inner City Life," inside a 21-minute opening track. (The opener on his next album, 1998's Saturnz Return, runs an hour long.) Grounded by vocals throughout from the late Diane Charlemagne, Timeless brought widescreen validation to an underground culture. Recognized as a key moment in dance music history by The Guardian, the album became a surprise Top 10 hit in the U.K. "Timeless was a f*cking good blueprint," the producer told Computer Music in 2017. "There were ten years of my life in that album."

The mid-'90s also introduced one of the dominant dance headliners of the next 25 years, sharing a tier with The Prodigy and two French upstarts called Daft Punk—that is, if Daft Punk played the festival game.

After a couple of releases as The Dust Brothers, including the propulsive steamrollers "Chemical Beats" and "Song To The Siren," Tom Rowlands and Ed Simons became The Chemical Brothers with 1995's Exit Planet Dust. (The Dust Brothers name already belonged to a songwriting/production team out of Los Angeles.)

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//4QKi8DorEpM' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Exit Planet Dust contains none of the reticence you might expect from a debut album. Right from the sleazy chug of opener "Leave Home," it's a dance record with classic rock heft. Even the hippieish cover art, lifted from a 1970s fashion shoot, references a world beyond the rave. (A favorite of early fans, Exit Planet Dust set the stage for the true breakout of 1997's Dig Your Own Hole, which featured the group's career-defining single, "Block Rockin' Beats.")

Crucially, "Chemical Beats" and "Song To The Siren" put The Chemical Brothers on lineups alongside fellow gear geeks Underworld, Leftfield and Orbital. Each act brought a version of their studio hardware to the stage, working the synthesizers, drum machines and mixing consoles under the cover of darkness.

This period of live innovation dovetailed with the superstar DJ phenomenon, ushered in by landmark mix albums like Sasha & Digweed's Northern Exposure (1996) and Paul Oakenfold's Tranceport (1998). A new rank of DJs, predominantly British and male, commanded skyrocketing fees, foreshadowing the excesses of America's own EDM boom more than a decade later. In the run-up to the 2000s, DJs and live acts struck a sometimes-uneven alliance. Fast-forward to Miami's dance massive Ultra Music Festival in the 2010s: DJs represented the main stage status quo, with live acts neatly billed in their own amphitheater.

In the pre-Facebook days of the mid-'90s, dance stars turned to magazines to vent or cause mischief. Aphex Twin, who released his bracing third album, …I Care Because You Do, in 1995, enjoyed derailing interviewers with fanciful responses. Goldie took the opposite approach, talking on and on without a filter. Ed Simons of The Chemical Brothers, on the other hand, got right to the point.

"I'm amazed at the low expectations which have always been centered on dance music," Simons told Muzik Magazine in 1995. In the same interview, he rankled at the critique that his music lacks soul: "Not everyone wants to be like Portishead, making music for people to put on when they have little dinner parties." (Later, in a 1997 Paper profile, Björk mocked America's adoption of The Chemical Brothers as electronic saviors: "The Chemical Brothers are hard rock!")

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//KFeUBOJgaLU' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

In the U.S., the top-selling album of 1995 was Hootie & The Blowfish's Cracked Rear View, ahead of the likes of Mariah Carey's Daydream, 2Pac's Me Against The World and The Lion King soundtrack.

Alanis Morissette's Jagged Little Pill went on to win big at the 1996 GRAMMYs, picking up the Album Of The Year award. For now, dance acts were left watching the party from the kids' table. (The GRAMMYS would later introduce the Best Dance Recording category in 1998.)

By 1997, dance music's outsider reputation was starting to shift, thanks in large part to the streak of groundbreaking albums two years prior. The Prodigy, previously overlooked in the U.S., sparked a label bidding war for its third album, The Fat Of The Land; Madonna's boutique imprint, Maverick Records, won out. Propelled by a polished big beat sound and the introduction of livewire hype man Keith Flint, The Fat Of The Land went to No. 1 in the States. That year, the floodgates opened, delivering Daft Punk's Homework, The Chemical Brothers' Dig Your Own Hole and Aphex Twin's still-creepy Come To Daddy EP.

Lollapalooza's 1997 lineup, in turn, looked a lot different from its 1995 run. This time, founder Perry Farrell brought electronic music to the fore. The change-up had mixed results: Attendance overall was down, The Prodigy protested the venue choices, Orbital and fellow U.K. beatmakers The Orb had to follow Tool, and Tricky felt askew sharing a main stage with Korn. But Lollapalooza's gamble signaled changing times.

Coachella debuted in 1999 with The Chemical Brothers, Underworld and Moby among the headliners. Like Glastonbury before it, the new desert festival even had a dedicated dance tent: the Sahara stage. At last, the underdog genre of 1995 had stepped into the light.

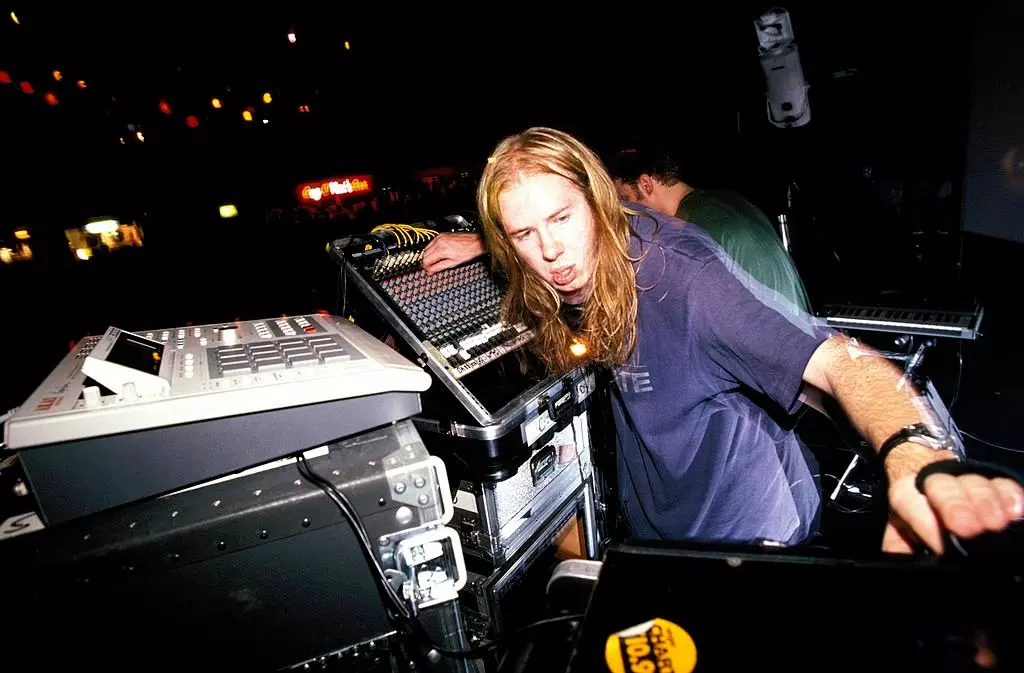

Photo: Shervin Lainez

interview

Cults' Evolution: Madeline Follin & Brian Oblivion Discuss Their Upcoming Album 'To The Ghosts'

Out July 26, Cults' new album reflects their 15-year journey as artists. Ahead of their Lollapalooza performance and U.S. tour, the duo discuss how they've pushed their sound forward.

Over the past 15 years, Cults have captivated audiences with their atmospheric, layered compositions that pack a pop-friendly punch. Now, on the brink of releasing their fifth album, To The Ghosts, on July 26, Madeline Follin and Brian Oblivion reflect on their journey and new creative freedom.

While their previous albums required the duo to stick to deadlines precariously organized between tours, the pandemic provided new circumstances. Freed of distractions and obligations, Follin and Oblivion traveled to Los Angeles in 2022 to join up with their longtime producer Shane Stoneback (Vampire Weekend, Sleigh Bells) to craft an album that looks back on their past while pushing their sound ahead.

"We don't have the sales pitch for the album down yet, but there's no other band that sounds like us," says Oblivion. "We're digging into our thing, and if you're into anything we've done before, you'll love this one."

Adds Follin, "We're like no other."

The album title is addressed to the ghosts of both Oblivion and Follin's past selves. As Oblivion explains, their four prior albums were time capsules that reflected the period in which each album was written and recorded. This release is something different.

To The Ghosts is a personal landmark for Follin, particularly. In 2020, upon the release of Cults' fourth album Host, she admitted that she'd been too shy to bring her own songwriting and demos to the table for the band's first three albums. It was Stoneback's encouragement that altered the creative process for the duo, resulting in their most collaborative album to date, and significantly more reliance upon live instrumentals in the studio.

"We spent a month in an AirBnB then a week in the studio with Shane," explains Follin.

"It was a mad dash to replace all the midi instruments with real ones, so we were running around playing vibraphones, organs, and guitars and all these things we'd recorded in demos and laying it all back down in one week."

It may have been a mad rush at the end, but over the years the duo have refined their formula for making albums. They're no longer the giddy art students and lovers making DIY music with no plans for world domination.

In 2010, Follin and Oblivion founded Cults and released their debut EP "Cults 7", followed by their debut self-titled album in 2011, which was similarly lauded. By the time their sophomore album "Static" arrived in 2013, the pair had freshly broken up and the themes of being creatively and emotionally stagnated resonated in dramatic, spacious orchestral compositions. They followed up with "Offering" in 2017, which was the first of the duo's albums to lean into optimism and a sense of embracing a more pop-friendly path.

That optimistic pop thread is picked up once more in "Crybaby", the first of 10 tracks that kicks off the new album. It launches with a lush, reverb-rich guitar hook and shuddering church bells, then shifts into a calypso beat and Follin's dreamy ode to escaping the modern malaise ("dry your eyes / turn off the screen"). Like the other catchy, bittersweet synth-pop numbers on To The Ghosts, "Crybaby" wraps up in close to three minutes.

The lengthy outliers are "You're In Love With Yourself" and the closing track "Hung The Moon," which runs over five minutes. Ending an album with an epic power ballad is their signature style and "Hung The Moon" bathes in drama, love, loss and redemption. "In a storytelling way, that's the only ending that makes sense to us, a melancholy resolution," Oblivion says.

To The Ghosts captures everything fans adore about Cults and they'll have ample opportunity to catch them performing live this year. The duo are set to return to Lollapalooza opening for Vampire Weekend on Aug. 4, followed by their own headlining U.S. tour the same month.

Ahead of their intensive touring schedule, the duo joined GRAMMY.com on a group video chat from their respective homes in New York’s East Village one evening, to discuss their upcoming release.

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

You began working on this album during the pandemic. Tell me where you wrote and recorded material, and whether you did that together or separately?

Madeline Follin: We were writing and recording in Brian's spare room. Can you see him?

Brian Oblivion: This tiny room! [directs the camera around a room not much bigger than 7 x 10 feet].

Follin: I sat on that couch right there, and we spent a lot of time in that little room [laughs]. For the most part we were together for the entire thing.

**Madeline, you revealed that before making your fourth album Host, you were too shy to show your own music to Brian and producer Shane Stoneback. What broke that barrier down for you to fully participate in the creative process?**

It was really hard to get it out of me. I had really strong imposter syndrome. Even though Brian was just starting out, he had taken a few recording classes in college, so he knew a lot more of the recording lingo and ways of communicating technically. I didn't know, so I felt so nervous to even communicate what I wanted. Shane helped with that a lot in terms of translating what I wanted into the language of studio speak. Shane is unlike any other producer we've worked with. He heard me out.

Tell me about working with Shane Stoneback in terms of what you came into the conversation with, and what he contributed to shaping this album.

Follin: We thought that we were not going to work with Shane again because he'd largely gotten out of the business. During [the] pandemic he switched careers and began working in the movie business. So, we started working with a few other people, we were feeling it out, and it just wasn't working. We reached out to [Shane], and he randomly happened to have 30 days off and said if we can finish it in 30 days, we can do it. We said, "we're coming out tomorrow."

What were the creative decisions you made in the earliest stages, and how much did you change your mind or allow outside ideas in as you were working on this album?

Oblivion: It took us a really long time. We definitely wrote over 100 songs. I put it all on an iTunes playlist and it was over 6 hours of music. This time we got a lot of confidence from some of our older songs being popular with young people. We thought, maybe the time has come around where we can do exactly what we do, and that's kinda 'new' again. Once we went through all the permutations and landed on "Crybaby," which was the first song on the record, we just thought "this just feels like us, so let's lean into what makes us unique." The messing around period was just trying out new tricks and trying to expand our possibilities.

John Congleton has a real knack for guitar sounds and finding a rawness to live instruments. How did he come to mix this album?

Oblivion: I've been a fan of John's going back to Xiu Xiu and my high school days. He's a master of distortion, him and Dave Fridmann, that's their thing. They can make things really fuzzy and interesting, but also fit it all in the speakers in a way that's like a weird magic trick. We have kind of a vintage sound, and he gets that but he's also smart at highlighting things that are new. He mixed our last record too and from the first conversation, in which he said he thinks like a musician and wants to do something strange, we knew we wanted him.

Follin: We'd mixed with other people before but when we got a mix back from John, he was bringing out parts of the song that we hadn't even recalled leaving in there. He makes our songs sound new to us again. We have a lot of trust and respect in him, and we were trying for so long to get our schedules lined up.

Oblivion: We work on our music for so long that by the time it's ready for the mix, we really want to hear something new. It's refreshing for us that John hears something new in us.

Tell me about "Crybaby," the first single. What were you going for in terms of the music, the mood and the message?

Follin: We'd been working on that song as part of the 100 songs that didn't make it. Brian started working on that song and I had never heard anything like that come out of his computer before, and I was shocked. It's funny because people say it's so "Cults sounding", but I thought it was unlike anything we'd done before. It's got a '60s vibe, an island vibe, to me and I thought we needed to zone in on it.

Oblivion: That was at the point where we decided "let's see if we can still make Cults songs that hark back to the earliest record." I love the lyrics, they're simple and there's no hidden meaning, which is great. A lot of the music that we love and that inspired the start of our band, is really obvious but also really weird in terms of lyrics. "Crybaby" is a fun, whacky diss track.

Let's talk about what inspires you musically.

Oblivion: What gets me excited is spending a lot of time sharpening my Spotify algorithm, so every Monday I get a collection of weirdo emotional love songs about heartbreak, these obscure, catchy B-sides, and whenever I find a song like that, I'm so inspired. Something that has kitsch, gravitas, and a bit of humour, that John waters, David Lynch combination lights me up.

Follin: Right now, I'm really into a lot of Fontaines D.C. I felt a 'Cults' vibe from them even though they probably have no idea who we are. It's been a while since I've put on a song, and then I want to put it on again right away.

"Left My Keys" is an anthem for growing up. Tell me about your experience growing up in this band.

Oblivion: What makes this record different is that historically, we'd do all the music together over a span of two years, then Maddy would squirrel away to take a month or two to write all the lyrics, and that made the records very reflective of that moment, that time. For this record, because we had a protracted work schedule with nothing else to do, we took the time to slow down and look back. "Left My Keys'' is about being a teenager, and "Crybaby" is about things that happened a long time ago. Growing up is being comfortable enough to address your own past and realizing everything turned out okay so far. It's the first album where we're looking backwards and processing stuff from the last 15 years and before.

This album feels brighter than 'Host.' What happened between 'Host' and 'To the Ghosts' that explains the transition?

Oblivion: There's a lot of stuff we got out of our system. Host and Offering were both dark records, to me. It's wild to see that young people have picked up on "Gilded Lily" and that was such a crazy, cathartic song for us, so now it is crazy and cathartic for them. Most of my favorite bands are dark, sad bands, but that's not the totality of who we are. Being able to explore both sides of who we are was refreshing for us.

Follin: Personally, we were both feeling a lot better in our lives. We worked through a lot of anxiety, and because of the pandemic there was less partying, clubs, and bars. We had time to get healthier.

Oblivion: In a lot of ways our band is defined by our limitations. We have made music for 15 years, just the two of us with the same producer. But every time we make something new and interesting and all the things we think of as roadblocks help to provide a framework for what we do.

You released 'Host B-Sides & Remixes' in 2022, two years after 'Host.' Are there outtakes, or planned remixes, that are planned for this album too?

Follin: Definitely. 100 percent, we will be having something, but I'm not saying.

Oblivion: It's been really fun with the last few albums to put out songs that showed what would have happened if we went in a different direction. Sharing that part of the process with listeners has been fun.

You have a huge schedule of touring. Tell me about the plans and how you mentally and physically endure all the travel and performances. Does it get easier the more you do it?

Follin: No. Every single night, even if we're in the middle of nowhere, whether there's 15 people or 1000, I almost have a heart attack before walking on stage each night. You're crammed in a box with 7 people every night, there's a lot of emotions…

Oblivion: …and something is always breaking at soundcheck, it's like arghhhh! It's really hard, but when we put out Host and we didn't get to tour for two years, we missed that connection. The feeling of sharing your music with people allows us to move past it and get into something new. It's a big part of our personal growth and experience. We love touring.

Follin: In normal daily life, we hang out together. We hang out on weekends. It's not a forced thing. It feels so good to meet fans every single night, too, and hearing stories of how you affected somebody's life.

Most of the tracks on this album fall at around the three minute mark, and many end quite abruptly without fading out or dwindling down. Was that a deliberate strategy, and then why did "Hung The Moon" require that extended time as the finale?

Oblivion: It's verse-chorus-verse-chorus-bridge-chorus and you're done in three minutes!

Follin: Brian is very concerned about time, and I don't think it matters. I like shorter, he likes longer. We're compromising.

Oblivion: "Hung The Moon" is the big epic ballad that ends the record. We have had one on every record, it always ends with a big power ballad. In a storytelling way, that's the only ending that makes sense to us, a melancholy resolution. I love that song because it starts off as a sweet love song then it gets tense and spooky towards the end, but the lyrics stay really loving. It's that transition between the rush of an initial relationship and then the long game, where it's sweet and delicate, but it's also real life, so you're afraid that you'll lose things and you're trying to hold on to that original thing. So, the album ends on a bittersweet note.

Lollapalooza News

Cults' Evolution: Madeline Follin & Brian Oblivion Discuss Their Upcoming Album 'To The Ghosts'

'Lolla: The Story of Lollapalooza' Recounts How An Alt Rock Fest Laid The Blueprint For Bonnaroo & More

From Tokyo To Coachella: YOASOBI's Journey To Validate J-Pop And Vocaloid As Art Forms

Lollapalooza Announces Lolla2020 Virtual Fest Celebration In Place Of Cancelled In-Person Event

How 1995 Became The Year Dance Music Albums Came Of Age

Photo: Dana Trippe

interview

Finding 'Comfort In Chaos': John Summit On The Journey To His Debut Album

"I always wanted to do an album," the DJ/producer says of 'Comfort in Chaos.' Although Summit has graced many major stages, creating his full-length debut took "over 10 years of producing and eight years of releasing music to get confident enough."

"I'm a little hungover, but I'm hanging in there," John Summit admits with a chuckle. The DJ/producer had stayed out late the night before (as DJs typically do) but for once, it wasn’t for work. Instead, he and his friends went bar- and club-hopping — "normal people stuff," Summit calls it. When asked how often he gets to do that these days, he laughs again. "Literally never. I felt like it was the first time in years."

Given the past few years, it’s understandable. Summit was still early in his career when he released his breakout hit, 2020’s "Deep End," a couple months into global lockdown. He maintained that momentum with a long string of releases including "Thin Line" with Guz, "Sun Came Up" with Sofi Tukker and "Human," the latter producing his first U.S. Dance Radio No. 1.

When live events powered back up, Summit quickly graduated to playing major venues and main stages. In the last two years, he’s DJed everywhere from Movement Detroit to Manchester, Turin to Tulum, and NYC to nearly every Ibiza superclub; in between, he launched his Experts Only record label. This year, Summit closed out EDC Las Vegas and Coachella; in June, he headlined a show at Madison Square Garden. Being a dance music superstar is a marathonic job, but a glance at his off-the-cuff social media posts suggests he’s more than up for the challenge.

Despite his hectic schedule, Summit somehow carved out time to write his debut album, Comfort in Chaos. In a way, it showcases his past, present and possible future. Recent single "EAT THE BASS" delivers the booming energy of the club tracks upon which he made his name; others, such as Billboard Top 10 hits "Where You Are" and "Shiver" with Hayla, are examples of his current evolution into lyric-focused songs, equally rich in melody and emotion. There are more surprises, still, as Summit explores sounds beyond his house and techno playground. "[This is] exactly the kind of music I've always wanted to make," he says, "but I never had an outlet or a reason to because they're not dance-floor-focused tracks."

The album’s sonic extremes also represent the duality between John Summit, the artist we see living his best life, one party at a time; and John Schuster (his given name), who’s introspective, who isn’t always confident, and who’s experienced "the lows" of returning from a show to an empty hotel room. "Now I'm comfortable where I am in life and I feel like I can tap into that [emotion]," he says. "It's cool to be able to show that side of me."

Before Comfort in Chaos’ release on July 12 via Darkroom/Experts Only, Summit tells GRAMMY.com how he got to this milestone.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

How long has the idea of a debut album been in your mind?

It's been in my mind since the day I started making music. I really got into songwriting four years ago. I did "Summertime Chi" with Lee Foss, which is an original written vocal, and then I did "What A Life" with Stevie Appleton a year later. That was received really well by my fans and I'm like, Oh, I don't have to just use samples. I can actually write completely original music.

Ever since then, the music has gone crazy. The first single off the album that I made was "Where You Are" with Hayla, which came out over a year ago, and that's when I feel like the ball really started rolling. In November, I took a month off and wrote pretty much the whole album in London and it really all came together then.

An entire month off? That seems rare.

Yeah, it's insane for me. I haven't taken a month off since I started touring, but I knew I had to do that, especially to make music that's not just meant for the dance floor. I produce on the go. I produce on planes and everything, but when you're always playing shows, you always make music just for the shows.

When you can actually take time off, I feel like you can make music that's actually meant for those rainy London days meant for just chilling with friends and stuff like that. So it was cool to make an actual body of work instead of just festival music.

What did that month look like for you in terms of the creative process?

I got this studio house for a month; this crazy house that has a couple of studios in it. My bedroom's at the top and I would take a slide down to my studio literally from the bedroom. I had a session every day for 30 days straight, and I just invited all the singers and producers I worked with. Sub Focus for example, he lived in London and then Hayla, Julie Church, Paige Cavell.

Pretty much everyone I work with is UK-based, so it was kind of a no-brainer to go to London for that. It was a lot of fun because we just make music all day, then drink at night and party. That's when you can share all your ideas with other people, at night when you're having drinks, wanting to call it banter. It was great.

To speak more about the variety of music that you make: You initially broke out with very club-forward tracks like "Deep End." But as you said, you've since honed a more melodic, songwriting-based sound. Was it a conscious evolution or did it just gradually happen over time?

I feel like it was just an evolution as an artist. House music is a very loop-based sound where it's, what, a four-by-four kick drum and an eight-bar loop… I kind of graduated from that to doing full-written songs [like] "Where You Are." But it took a lot of time.

I was always writing songs during that process, but they weren't good. Writing a full song, it's like going from a short film to a movie. I always wanted to do an album, but it really did take me over 10 years of producing and eight years of releasing music to get confident enough to be able to do this.

How do you tap into the emotion of those songs, especially given the image that you portray online?

I guess that's the whole purpose of the album: That I've been portraying this John Summit image my whole career, but in reality I'm John Schuster. The John Summit image is obviously an entertaining party guy that loves to have a good time; in reality, outside of the club, I'm just sitting at home making music, and I want to show the more introspective side of me.

I've been neglecting my emotions the past few years, especially after quitting the accounting job five years ago. Then I was just in this full party mindset, but now I'm comfortable where I am in life and I feel like I can tap into that. So it's cool to be able to show that side of me.

Who is that more introspective John Schuster?

Someone that, I guess, shows that I'm not really a 100 percent confident all the time. That I've experienced very high highs, but very low lows as well. I mean, John Summit has the biggest highs on stage, but then I go back to my hotel room and I'm by myself and experiencing the lows and being by myself all the time. So I guess showing that kind of emotional side is fun for my music at least.

Absolutely. I imagine it’s difficult going not from zero to a hundred, but a hundred to zero.

Exactly. That's the hard part. Zero to a hundred is the fun part.

If debut albums are like an artist's mission statement, what do you want 'Comfort in Chaos' to say?

I think kind of what I was just touching on, the duality of John Schuster and John Summit. This is the first time I've fully shown my other half. I've been showing it through singles: "Where You Are," "Go Back," "Shiver" and stuff. But to do it in a full album where — especially the intro track where there's really no vocals on it, and it starts experimental and a bit progressive, and then the drop is really just a kick in bass. It's tension-release, which I love in music, but it just shows, not to be too pun intended, the comfort in the chaos that is my life right now.

What brings you comfort in chaos?

That's a good question. Honestly, it's more so me trying to find my comfort in chaos. Because the thing is that if I'm on stage every night, I’ve got to be comfortable up there. The more confident I am, the better show that I do. And so I think I'm finding it now.

It's kind of the whole fake it till you make it. At first I had to get hammered every single night just to get on stage, and now I can get up there without doing that, which is a big stepping stone for me.

So it seems like it's more about the journey than the destination.

Exactly, exactly. It's basically trying to find my comfort in chaos. And I think I've gotten there, so now is the perfect time for the album. I couldn't release that while I'm still not comfortable.

Given how significant Kaskade and deadmau5’s "I Remember" is to your electronic music journey, it must feel very special to have Kaskade on the album.

Yeah, it was kind of a no-brainer. I was able to remix "I Remember" last year, which is huge for me. The track that literally got me into electronic music. Kascade is also from Chicago, and he's the one that introduced me to Hayla, too.

We've been trying to make something work and we just didn't know what direction to go with it. It took a while, but we both love melodic and emotional music and we both love heavy techno, and so we made it work in one song, which is great because the track starts very comforting and it gets very chaotic, so it's very on-brand with the album.

What have you learned from Kaskade, whether directly or from afar?

I've learned patience, and that everything's going to be okay. I'm a very neurotic person; I am very anxious and worry about every little detail, and he's the coolest, calmest guy I've ever met. I think it has to do with just his experience in the scene. Everything I'm experiencing is something he's experienced at some point in his DJ career, and even before Coachella, I was like, "Man, I don't know if I can do this" And he was like, "Bro, you got this. It's easy. Play your music." And I'm like, "Oh s—, you're right." It’s as simple as that. Yeah, he's been a good mentor.

To borrow a word that you've used in another interview, being "unhinged" on social media has played a significant role in building your fan base over the years. How has your relationship with social media changed in terms of the content you share and fan interactions?

I'm still definitely unhinged on social media. That hasn't changed, but it has made me not afraid to show all facets of myself. I've just started showing the more emotional and deeper side of myself, but it is cool that I can say no matter who I am, I have good days and bad days. The fans can connect and resonate with that, which is cool because it was annoying growing up and following artists who are perfect on social media all the time. So I try to be as transparent as possible.

Given the positive response to your collaboration with Subfocus, do you feel more encouraged to get eclectic in your future music?

The Subfocus one was still pretty dance-floor-focused, and I still haven't released anything that's not dance-floor-focused. I mean, obviously in the album there is with the intro, with "Calm Down," with "Undo," with ["Palm of My Hands"] and ["Stay With Me"], so I'm waiting to see how fans like that. But at the end of the day, though, I’m at the point in my career where I don't have to put out things just to please dance floors. I feel like I've kind of made it where now I can experiment more and take risks. Now is when my career is starting to actually get fun.

Latest News & Exclusive Videos

Watch Henry Moodie Share His Epiphone Guitar

Still Barking After All These Years: Dr. Dog On Low-Key Longevity And Their New Self-Titled Album

Cults' Evolution: Madeline Follin & Brian Oblivion Discuss Their Upcoming Album 'To The Ghosts'

Koe Wetzel On How New Album '9 Lives' Helped Him Tap Into His Feelings

The New GRAMMY GO Music Production Course Is Now Open: Featuring GRAMMY Winners Hit-Boy, CIRKUT, Judith Sherman & More

Photo courtesy of Prism Artists

list

Meet The Artists Bringing Back UK Jungle: Nia Archives, SHERELLE & More

First developed in the 1990s, a new generation of UK musicians — particularly queer individuals and women of color — are reviving jungle music. From Tim Reaper to PinkPantheress, envelop yourself in the experimental sounds of the genre.

In the early 1990s, a bombastic new type of music was emerging in the underground Black British scene of London. Jungle was a frantic mixture of breakbeats and reggae featuring fast beats that splintered into myriad directions, interspersed with vocal samples.

Thanks to pirate radio stations, jungle saturated the streets of London’s predominantly Black, working-class neighborhoods. Jungle was a sound of escapism, celebration, community, crafted by the children of immigrants of post-war Britain.

Junglist historian Julia Toppin notes in her essay "Tech, Language and Riddim: From Jungle to UK Drill" that jungle "snatched bites from young Black Britain’s sonic palette of genres: reggae, hip-hop, pop, house, soul, RnB, groove, punk, jazz, folk, and classical," with artists like Goldie, Shy FX, A Guy Called Gerald, General Levy leading the scene. By the latter part of the decade, jungle offshoots like drum and bass gained prominence, causing the jungle scene to gradually fade into the background.

Today, a new generation of UK musicians are waking up the scene — a revival spearheaded by queer individuals and women of color. As contemporary junglist Nia Archives told GRAMMY.com, jungle is "anything over a breakbeat" — it simply refuses to conform: "The breaks have so much room to go in whatever direction you want. You can go really heavy, or you can go really light and atmospheric," she said.

It’s a flexibility that she takes full advantage of across her releases. Nia Archives layers beats with everything from pensive, thoughtful lyrics and RnB melodies ("Cards on the Table", "So Tell Me"), to rave abandon ("Baianá", "Forbidden Feelingz", "Unfinished Business")

Nia Archives is taking her debut album, Silence is Loud on the road, stopping at summer festivals including Chicago’s Lollapalooza before touring the U.S. in the fall. She is one of many contemporary jungle artists boldly experimenting with unrestrained beats, earth-shaking basslines and intricate percussive patterns to breathe new life into the pulsating rave scene.

Here are seven other artists who are bringing jungle back.

SHERELLE

Former Mixmag photographer SHERELLE gained widespread attention after a 2019 Boiler Room viral set, followed by the release of "JUNGLE TEKNAH" in 2021, which layers piano house chords onto jungle beats. Her latest single, "Henry’s Revenge," features ethereal synths over dramatic bass drops.

Fresh from a completely sold-out international tour, SHERELLE will play a New York Boiler Room set on July 14, alongside Afrobeats star Amaarae and UK rapper Giggs.

Sully

One of the slickest in the game, Sully is a pioneer of today’s revival and has been on the scene since 2005. His beats are methodical, with tight percussion flawlessly mixed into hours of ecstatic jungle harmony. On 2024 single "Nights", he teams up with jazz singer Sâlo to create a dreamy and contemplative dancefloor meditation.

He continues to inject energy into the club, with massive sets featuring the likes of grime MC Flowdan and B2B’s with fellow junglist Tim Reaper, and is playing several UK festival slots over summer.

GROVE

GROVE harnesses jungle’s unmatched energy to voice political despair. "The stinking rich families, you know how they anger me," they spat on last year’s single "Stinkin Rich," where trippy beats erupt into a heavily distorted chorus.

Their 2022 breakout hit, "Feed My Desire," is sensual, with hushed whispers and soft verses underscored by blaring basslines, demonstrating GROVE's mastery of mood — ranging from rage to seduction.

PinkPantheress

PinkPantheress didn’t come up through a club or rave scene, by anonymously uploading songs to TikTok, which she made in her bedroom during the COVID-19 pandemic. Her sped-up vocals and luscious hooks nodded to the heyday of 2000s UK Garage (UKG) (a jungle offshoot), quickly drumming up a viral following online.

Last year, the 23-year-old broke into the U.S. thanks to the massive UKG track "Boys A Liar pt 2" featuring Ice Spice, which now has over 200 million views on YouTube. A lover of throwback genres and a fan of jungle veterans like Shy FX, PinkPanthress combines breakbeats with pop melodies and emo guitar riffs, a delicious mix that’s made her one of Gen-Z’s fastest-rising pop stars.

Tim Reaper

Tim Reaper is a London native who has pushed the jungle revival for over a decade. His music includes reggae-influenced ragga samples (one of jungle's key influences), chill synths, and can go both hard and soft.

In 2020, Tim Reaper launched club night Future Retro to showcase London’s budding scene. However, the pandemic lockdown led the event to morph into a new-skool jungle record label that highlights some of the genre's hottest artists, including Sully, Mantra, and Decibella.

Shy One

London-based DJ Shy One has been making music since she was a teenager, coming up through the ranks as a selector on legendary Hackney-based online radio NTS Radio.

Her music is shaped by grime, soul, house and jungle, and she’s taking her versatile sets to a handful of European festivals this summer. Her latest single, "Gyallis Spiral," combines rubbery bass lines and scattered synths, giving it a uniquely hyper-futuristic, spacey feel.

LCY

LCY is an artist and owner of the experimental label S7NS7N whose music is, by design, indescribable. Their tracks are leftfield and surreal; the mere act of listening is an out-of-body experience.

Their 2023 EP He Hymns is a celestial exploration of club music hinged on breakbeats, heavy bass, disorientating drops and haunting vocals. You’re not sure what’s going on, but jungle is one of the many genres that form a kaleidoscope of their mind-bending sounds.

Latest News & Exclusive Videos

Watch Henry Moodie Share His Epiphone Guitar

Still Barking After All These Years: Dr. Dog On Low-Key Longevity And Their New Self-Titled Album

Cults' Evolution: Madeline Follin & Brian Oblivion Discuss Their Upcoming Album 'To The Ghosts'

Koe Wetzel On How New Album '9 Lives' Helped Him Tap Into His Feelings

The New GRAMMY GO Music Production Course Is Now Open: Featuring GRAMMY Winners Hit-Boy, CIRKUT, Judith Sherman & More

Photo: Mike Formanski

interview

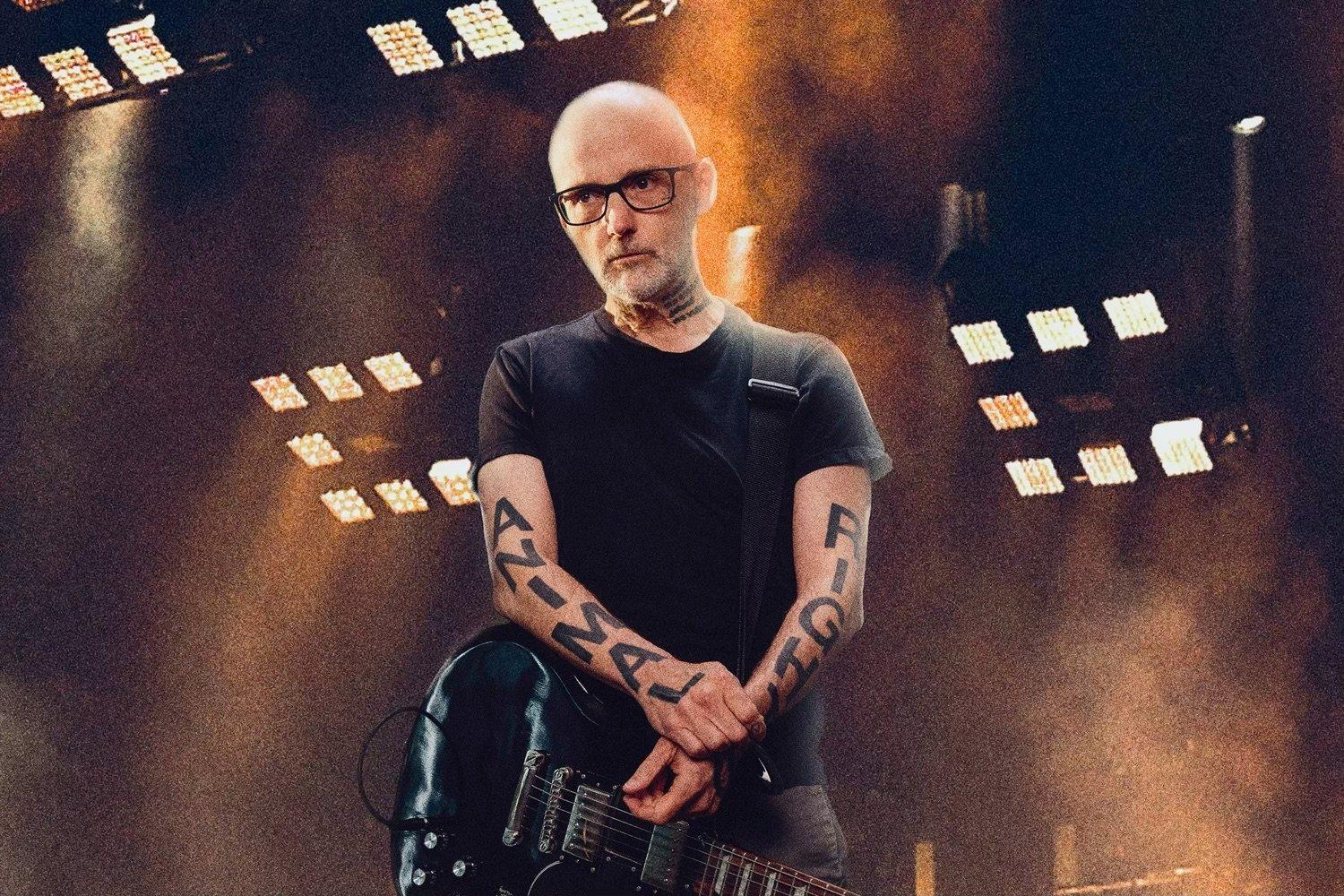

"Let Yourself Be Idiosyncratic": Moby Talks New Album 'Always Centered At Night' & 25 Years Of 'Play'

"We're not writing for a pop audience, we don't need to dumb it down," Moby says of creating his new record. In an interview, the multiple-GRAMMY nominee reflects on his latest album and how it contrasts with his legendary release from 1999.

Moby’s past and present are converging in a serendipitous way. The multiple-GRAMMY nominee is celebrating the 25th anniversary of his seminal work, Play, the best-selling electronic dance music album of all time, and the release of his latest album, always centered at night.

Where Play was a solitary creation experience for Moby, always centered at night is wholly collaborative. Recognizable names on the album are Lady Blackbird on the blues-drenched "dark days" and serpentwithfeet on the emotive "on air." But always centered at night’s features are mainly lesser-known artists, such as the late Benjamin Zephaniah on the liquid jungle sounds of "where is your pride?" and Choklate on the slow grooves of "sweet moon."

Moby’s music proves to have staying power: His early ‘90s dance hits "Go" and "Next is the E" still rip up dancefloors; the songs on Play are met with instant emotional reactions from millennials who heard them growing up. Moby is even experiencing a resurgence of sorts with Gen Z. In 2023, Australian drum ‘n’ bass DJ/producer Luude and UK vocalist Issey Cross reimagined Moby’s classic "Porcelain" into "Oh My." Earlier this year, Moby released "You and Me" with Italian DJ/producer Anfisa Letyago.

Music is just one of Moby’s many creative ventures. He wrote and directed Punk Rock Vegan Movie as well as writing and starring in his homemade documentary, Moby Doc. The two films are produced by his production company, Little Walnut, which also makes music videos, shorts and the podcast "Moby Pod." Moby and co-host Lindsay Hicks have an eclectic array of guests, from actor Joe Manganiello to Ed Begley, Jr., Steve-O and Hunter Biden. The podcast interviews have led to "some of the most meaningful interpersonal experiences," Moby tells GRAMMY.com.

A upcoming episode of "Moby Pod" dedicated to Play was taped live over two evenings at Los Angeles’ Masonic Lodge at Hollywood Forever Cemetery. The episode focuses on Moby recounting his singular experiences around the unexpected success of that album — particularly considering the abject failure of his previous album, Animal Rights. The narrative was broken up by acoustic performances of songs from Play, as well as material from Always Centered at Night (which arrives June 14) with special guest Lady Blackbird. Prior to the taping, Moby spoke to GRAMMY.com about both albums.

'Always centered at night' started as a label imprint then became the title of your latest album. How did that happen?

I realized pretty quickly that I just wanted to make music and not necessarily worry about being a label boss. Why make more busy work for myself?

The first few songs were this pandemic process of going to SoundCloud, Spotify, YouTube and asking people for recommendations to find voices that I wasn’t familiar with, and then figuring out how to get in touch with them. The vast majority of the time, they would take the music I sent them and write something phenomenal.

That's the most interesting part of working with singers you've never met: You don't know what you're going to get. My only guidance was: Let yourself be creative, let yourself be idiosyncratic, let the lyrics be poetic. We're not writing for a pop audience, we don't need to dumb it down. Although, apparently Lady Blackbird is one of Taylor Swift's favorite singers.

Guiding the collaborators away from pop music is an unusual directive, although perhaps not for you?

What is both sad and interesting is pop has come to dominate the musical landscape to such an extent that it seems a lot of musicians don't know they're allowed to do anything else. Some younger people have grown up with nothing but pop music. Danaé Wellington, who sings "Wild Flame," her first pass of lyrics were pop. I went back to her and said, "Please be yourself, be poetic." And she said, "Well, that’s interesting because I’m the poet laureate of Manchester." So getting her to disregard pop lyrics and write something much more personal and idiosyncratic was actually easy and really special.

You certainly weren’t going in the pop direction when making 'Play,' but it ended up being an extremely popular album. Did you have a feeling it was going to blow up the way it did?

I have a funny story. I had a date in January 1999 in New York. We went out drinking and I had just gotten back the mastered version of Play. We're back at my apartment, and before our date became "grown up," we listened to the record from start to finish. She actually liked it. And I thought, Huh, that's interesting. I didn't think anyone was going to like this record.

You didn’t feel anything different during the making of 'Play?'

I knew to the core of my being that Play was going to be a complete, abject failure. There was no doubt in my mind whatsoever. It was going to be my last record and it was going to fail. That was the time of people going into studios and spending half a million dollars. It was Backstreet Boys and Limp Bizkit and NSYNC; big major label records that were flawlessly produced. Play was made literally in my bedroom.

I slept under the stairs like Harry Potter in my loft on Mott Street. I had one bedroom and that's where I made the record on the cheapest of cheap equipment held up literally on milk crates. Two of the songs were recorded to cassette, that's how cheap the record was. It was this weird record made by a has-been, a footnote from the early rave days. There was no world where I thought it was going to be even slightly successful. Daniel Miller from Mute said — and I remember this very clearly — "I think this record might sell over 50,000 copies." And I said, "That’s kind of you to say but let's admit that this is going to be a failure. Thank you for releasing my last record."

Was your approach in making 'Play' different from other albums?

The record I had made before Play, Animal Rights, was this weird, noisy metal punk industrial record that almost everybody hated. I remember this moment so vividly: I was playing Glastonbury in 1998 and it was one of those miserable Glastonbury years. When it's good, it's paradise; it's really special. But the first time I played, it was disgusting, truly. A foot and a half of mud everywhere, incessant rain and cold. I was telling my manager that I wanted to make another punk rock metal record. And he said the most gentle thing, "I know you enjoy making punk rock and metal. People really enjoy when you make electronic music."

The way he said it, he wasn't saying, "You would help your career by making electronic music." He simply said, "People enjoy it." If I had been my manager, I would have said, "You're a f—ing idiot. Everyone hated that record. What sort of mental illness and masochism is compelling you to do it again?" Like Freud said, the definition of mental illness is doing the same thing and expecting different results. But his response was very emotional and gentle and sweet, and that got through to me. I had this moment where I realized, I can make music that potentially people will enjoy that will make them happy. Why not pursue that?

That was what made me not spend my time in ‘98 making an album inspired by Sepultura and Pantera and instead make something more melodic and electronic.

After years of swearing off touring, what’s making you hit stages this summer?

I love playing live music. If you asked me to come over and play Neil Young songs in your backyard, I would say yes happily, in a second. But going on tour, the hotels and airports and everything, I really dislike it.

My manager tricked me. He found strategically the only way to get me to go on tour was to give the money to animal rights charities. My philanthropic Achilles heel. The only thing that would get me to go on tour. It's a brief tour of Europe, pretty big venues, which is interesting for an old guy, but when the tour ends, I will have less money than when the tour begins.

Your DJ sets are great fun. Would you consider doing DJ dates locally?

Every now and then I’ll do something. But there’s two problems. As I've become very old and very sober, I go to sleep at 9 p.m. This young guy I was helping who was newly sober, he's a DJ. He was doing a DJ set in L.A. and he said, "You should come down. There's this cool underground scene." I said, "Great! What time are you playing?" And he said "I’m going on at 1 a.m." By that point I've been asleep for almost five hours.

I got invited to a dinner party recently that started at 8 p.m. and I was like, "What are you on? Cocaine in Ibiza? You're having dinner at 8 p.m. What craziness is that? That’s when you're putting on your soft clothes and watching a '30 Rock' rerun before bed. That's not going out time." And the other thing is, unfortunately, like a lot of middle aged or elderly musicians, I have a little bit of tinnitus so I have to be very cautious around loud music.

Are you going to write a third memoir at any point?

Only when I figure out something to write. It's definitely not going to be anecdotes about sobriety because my anecdotes are: woke up at 5 a.m., had a smoothie, read The New York Times, lamented the fact that people are voting for Trump, went for a hike, worked on music, played with Bagel the dog, worked on music some more went to sleep, good night. It would be so repetitive and boring.

It has to be something about lived experience and wisdom. But I don't know if I've necessarily gotten to the point where I have good enough lived experience and wisdom to share with anyone. Maybe if I get to that point, I'll probably be wrong, but nonetheless, that would warrant maybe writing another book.

Machinedrum's New Album '3FOR82' Taps Into The Spirit Of His Younger Years