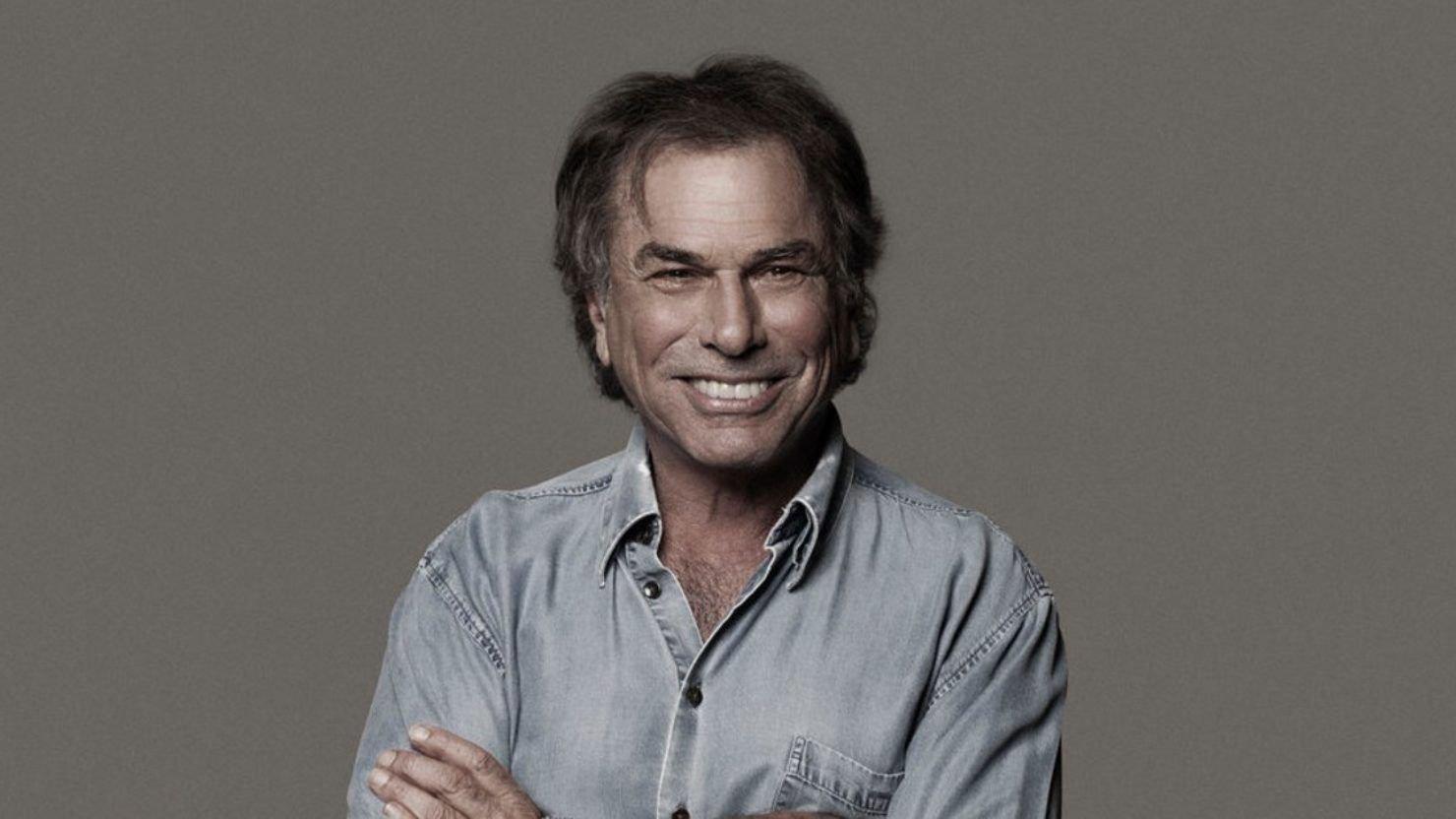

Photo: Leo Volcy

Michael Brun

news

Why The GRAMMY Awards Best Global Music Album Category Name Change Matters

"Global Music is the future of music…The fusion of sounds breeds innovation, and global music artists are at the forefront of that movement," Haitian DJ/producer Michael Brun told us

Last week, the GRAMMY Awards were in the news because of an exciting, timely update to one of its 84 categories: Moving forward, Best World Music Album will now be known as the more inclusive Best Global Music Album. While the change might appear subtle to those not familiar with the baggage the term "world music" carries, it represents an important honoring of its past and movement towards a more inclusive, adaptive future.

The new name was decided after extensive conversations with artists, ethnomusicologists and linguists from around the world, who decided it was time to rename it with "a more relevant, modern, and inclusive term," an email sent to Recording Academy members explained.

"The change symbolizes a departure from the connotations of colonialism, folk and 'non-American' that the former term embodied while adapting to current listening trends and cultural evolution among the diverse communities it may represent."

Read on to hear from three international artists about what the new Best Global Music Album name means to them, and why it's more inclusive than "world music."

Read: The 63rd GRAMMYs: Looking Ahead To The 2021 GRAMMY Awards

"Miriam Makeba used to tell me the expression 'World Music' was a politically correct way of calling our music 'Third World Music,' therefore putting us in a closed box from which it was very difficult to emerge. Now the new name of the category opens the box wide open and allows every dream!" GRAMMY-winning Beninese singer/songwriter Angélique Kidjo told us. The legendary artist won (what was then called) Best World Music Album at the 2020 GRAMMYs for her Celia Cruz tribute album, Celia, and at the 2016 and 2015 GRAMMYs.

Nigerian singer Bankulli, who is featured on Beyoncé's The Lion King: The Gift album, added, "Global Music provides a more inclusive awards platform to artists from relevant new genres. The term is encompassing of what is happening today and looks to the future for better representation."

"American ethnomusicologist Robert E. Brown coined the term in the early 1960s, but it was later popularized in the 1980s as a marketing category in the media and the music industry intending to encompass different styles of music from outside of the Western world. It is by and large a determination of any type of genre or sound that Westerners consider ethnic, indigenous, folk, or simply non-American music," Uproxx explained earlier this year.

As the Guardian recently noted, "the term 'world music' was originally coined [in the music business] in the U.K. in 1987 to help market music from non-western artists… Our world music album of the month column was, like the GRAMMYs, renamed global album of the month.

Guardian music critic Ammar Kalia reasoned that the change 'does not answer the valid complaints of the artists and record label founders who have been plagued by catch-all terms. Yet, in the glorious tyranny of endless internet-fueled musical choice, marginalized music still needs championing and signposting in the west.'"

The Recording Academy awarded the first Best World Music Album golden gramophone at the 1992 GRAMMYs to Grateful Dead drummer Mickey Hart for his album Planet Drum. A diverse group of artists, representing many countries and musical styles, including Brazilian bossa nova great Sergio Mendes, Panamanian salsa singer Rubén Blades and South African choir Ladysmith Black Mambazo have also won over the years.

"Culturally speaking, we are living in a borderless world. Changing our language to better describe and categorize influential music from around the globe allows us to hit a reset button on how we view each other. It allows us to have a better conversation about who we are and where we're headed," Marlon Fuentes, Genre Manager, Global Music, New Age and Contemporary Instrumental at the Recording Academy, shared.

"In my opinion, this moment was symbolic of a new era that connects the past to the future. A signal that we are living in a time where creative people from all over the world are using social media and innovative approaches to overcome clichés and stereotypes by defining their identity on their own terms."

"Global Music is the future of music. As the world continues to become more interconnected, music culture no longer has borders," Haitian DJ/producer Michael Brun said. "The fusion of sounds breeds innovation, and global music artists are at the forefront of that movement. I'm happy to see the Recording Academy working to adapt to the changing landscape and celebrate excellence from around the globe."

This summer, the Recording Academy announced updates to the names and rules for four other categories, which included renaming Best Urban Contemporary Album to Best Progressive R&B Album. Conversations around nixing the term "urban music," an umbrella category encompassing traditionally Black genres like R&B and rap, came to the forefront in 2020 following the deep reckoning with racism in American and beyond. Major labels, including Universal Music Group, including affiliates Warner Music Group and Republic Records, have dropped the term.

As Billboard notes, the Best Global Music Album rename follows a similar change implemented at the 2020 Academy Awards—Best Foreign Language Film was updated to Best International Feature Film. South Korean director Bong Joon-ho won for his widely celebrated 2019 film Parasite.

The 2021 GRAMMY nominees for Best Global Music Album—along with the other 83 categories—will be announced on Nov. 24. The 2021 GRAMMY Awards and Premiere Ceremony will take place on Jan. 31, 2021, when all the big winners will be revealed.

Get To Know The 2020 Latin GRAMMYs Album Of The Year Nominees | 2020 Latin GRAMMY Awards

Photo: Sven de Almeida

interview

Meet KOKOKO! The DIY Electronic Group Channeling The Chaos & Resilience Of Kinshasa

The exciting live electronic act out of the Congo discusses their fiery, pulsing, sophomore album, 'BUTU,' the manic sound of Kinshasa, and using improvisation to keep their performances energized.

No one else sounds like KOKOKO! — they are a truly unique aural experience, an emphatic statement that does justice to the exclamation point in their name.

The experimental live electronic group out of Kinshasa — the active, populous capital of the Democratic Republic of Congo — is a reflection of their city. Their shouted and chanted lyrics reflect people's frustration with their government, as well as the sonic signals of industrious local vendors. Even their DIY instruments are an example of their resourcefulness: Although DRC is a resource-rich country, that wealth has been extracted by and for Western powers for centuries. Locals are left with limited resources and experience regular power outages and intense, ongoing conflict.

KOKOKO! was born after French electronic producer Xavier Thomas — who makes left-field, globally-influenced electronic music as Débruit — met talented local singer and musician Makara Bianko on a visit to Kinshasa. He was captivated by Bianko's large, nearly daily outdoor performances with his massive dance crew. The group, which also consists of locals Boms and Dido who fashion DIY instruments, incorporate much of Makara's improvisational and interdisciplinary energy into their music and energetic live show, while Thomas brings in synths, drum machines and other electronic elements.

After releasing their powerful debut album Fongola in 2019 on indie label Transgressive Records, KOKOKO! started getting booked at music festivals around the globe, as well as on NPR's Tiny Desk series and Boiler Room. Now, the cutting-edge group is pumping up the BPM and bringing the lively Kinshasa nighttime to the rest of the world via their urgent, high-energy sophomore album, BUTU, on July 5 on Transgressive.

Read on for a chat with Thomas and Bianko about their captivating new album, the music scene in the Congo, how their music reflects Kinshasa, and much more. (Editor's note: Bianko's answers are translated and paraphrased from French by Thomas.)

What energies, sounds and themes are you harnessing on 'BUTU?'

Xavier Thomas: "Butu" means night in Lingala [one of the national languages of the DRC]. The album is all about that high energy, specific atmosphere that happens when the night falls in Kinshasa.

It's a very loud and crowded city. It gets pitch-black quite quickly because it's on the Equator. The sun sets really fast all year long. The sounds of the city kind of wake up [at night]; the generators are plugged in and the club music and evangelical church music [start] competing. All the inspirations are from all these sounds and everything that happens in the night in Kinshasa.

The band plays a lot of DIY instruments; what instruments are on this album and can you point to their specific sounds?

Xavier Thomas: There're the go-to things and then there's the found objects or the ones you can build. Simple things that are kind of ready-made, like detergent bottles — you can play it with a stick with a little bit of rubber, and it kind of makes bongo sounds with a slight natural overdrive.

And you can also build your own string instruments with what you found on the street. For example, there's plastic chairs that have metal feet, and you can do a kind of metallophone with; if you chop the tubes, you will get different pitches, etcetera. You can find something in a mechanic shop that sounds really good straight away when you hit it; metallic percussion. So that's all the different DIY instruments or found percussion that you can make or work with.

Was it mostly the same instruments as the first album, or were there some different things you were incorporating as well?

Xavier Thomas: There are different things. Also, on this one, we use a little bit more of electronics, as it's a bit more upbeat and influenced by the club and the small music production studios of Kinshasa.

There are also some field recordings. For example, on some tracks, there's horns from moto taxis that we pitched and made melodies with. But yeah, it's roughly the same instruments.

The term DIY is often attached to the band. Of course, you just talked about the instruments, but I was also curious what DIY and improvisation looks like in your music-making process and performances.

Xavier Thomas: It was an all-over DIY thing when we started. I used to make a lot of the videos. We [still] work with a small team, so we always have problems getting visas. We're doing a bit of everything just to keep going forward and traveling and to get our music everywhere. So, the DIY is not just the music, it's [all very] hands-on. Even on stage, we don't turn up with a big team, it's pretty much us at the moment.

The DIY aspect came out of necessity for the music and instrument creators, of not being able to afford to buy or rent an instrument. So it started like that, trying to make a one- or two-string guitar, a two-string bass, and a drum set. And then it went beyond that, realizing we can find original and new sounds if we're not copying existing instruments.

When I met Makara, he was doing five-hour public rehearsals six times a week on his own with 40 or 50 dancers. He had to work out all the technical problems with power cuts and amplifiers exploding. Makara still has that energy, even when we're sound checking. A lot of that DIY intuition is still coming in.

The recording process has to be DIY because you're recording in outside music studios in little compounds or in difficult neighborhoods of Kinshasa, so there's a lot of sounds in the background. You just grab the moment where the energy, the music, the inspiration feels right. That's another DIY part of the project, it's pretty much recorded outside of recording studios for the most part.

How does that also speak to access to instruments, internet and music studios for music-making in the DRC more broadly?

Xavier Thomas: Well, there's some big artists in the Congo that have a lot of money and travel to play even in the U.S. and France. A few artists have everything they want and they're very famous and wealthy. But most of the studios I've seen are a tiny room in the corner of a compound, yet people are doing the most impressive productions and recordings with very little, whether it's electronic or live music. It's very resourceful and sometimes you don't hear it, you could not imagine it would be coming from such a small studio.

I wish I could ask about every song on the album, because it feels like there's so much energy and context in each one. Can you tell me about the opening track, "Butu Ezo Ya" — the energy starts out so strong. Is there a message behind that song?

Xavier Thomas: The first track is kind of an invitation. It's saying the night's coming, be ready. We have all the sounds that we grabbed in the streets. That's the track where the horns of the motorbikes are pitched and turned into melodies. It's an invocation, an invitation, to the listener to step in the Kinshasa night because it's really something.

We wanted the opening track to be a little bit overstimulating, which is the impression you have the first time you step into the night in Kinshasa. So that's the idea, to [channel the] overwhelming street sounds that suddenly from chaos become organized and become the opener of the album to invite you to the more organized music after. [Chuckles.]

Makara Bianko: I'm inviting people to step into the night, step into the album.

The album's next track, "Bazo Banga," is really captivating as well.

Xavier Thomas: "Bazo Banga" means they are scared. Sometimes people chant it when they're protesting. It can also be used in sport events about the other teams. There's a lot of frustrations in Congo; the population is a bit abandoned by the government. Sometimes there are political things that can't be said or expressed because it's a bit dangerous. So, in this track — Makara has explained the lyrics to me before — it's a way to regain a bit of control by trying to impress the other side.

Makara Bianko: There's another angle mentioned at the end of the track: We're bringing so many new sounds that their hips are not going to hold. They are scared they are out of date, that they will not be matching our energy or be able to move because we're going too fast. During the track, I'm quoting a lot of images of why they could be scared.

Xavier Thomas: In Kinshasa, our sound is still very different. At the beginning, with all the music, art performers, people who do body performance as well, who gravitate around our music and are sometimes part of the videos; [other] people thought we were all so crazy. The music didn't fit any standards there, even though Makara has a lot of influences, more when he was younger, in more standard music like Congolese rumba or ndombolo. I think people can still be a bit scared of our style and our energy, the people we work with, it's a bit different.

In what ways is your music incorporating — as well as radically shifting — traditional and popular Congolese music?

Makara Bianko: Growing up in Kinshasa, there's a lot of Congolese rumba and nbombolo. I'm also influenced by [Congolese] folk music, really old rhythms and chants. Congo is so big that this has just been mixed in our music, but we are presenting it like it's a new recipe. It doesn't taste like what you're used to even though the ingredients are there. There's also influences [in our music] from outside countries like Angola or South Africa.

Xavier Thomas: What struck me the most when I first met Makara at this concert — from my Occidental angle — he has a very punk energy. Even though people aren't listening to punk music in Kinshasa, Makara would stick his mic in the speakers and play with feedback, and he has a very powerful voice and sometimes a very threatening singing tone. It was not influenced from punk; it was his own energy, his own frustration.

I think music helps express the frustration a lot of people have in Congo, and people see that in him, through his anger and when he talks about things people encounter on the street that they can relate to. So yeah, some of the old folk music is there as influences, but it's very important to him to not do the same thing that a lot of artists have done for the last 40 years and to bring something new.

What's going on in Kinshasa and the DRC in terms of electronic music? Are there other DIY electronic acts coming up?

Xavier Thomas: There's a lot of electronic music now, I think the big scenes are in South Africa or Nigeria for big pop electronic music. Congo used to influence a lot of West Africa and Central Africa and now Nigeria and South Africa have quite strong industries, so sometimes there's a bit of that influence.

With more Congolese rhythms for electronic music, you can have the whole range from very pop to very alternative. In the neighborhood where we started, there's a few more bands coming up now with DIY instruments who play a bit more like folk music from the Equator region in the north of the country. In Europe, I've noticed three bands since we started that now work with more DIY instruments. There's a music producer, P2N, from the southeast of Congo who makes repetitive electronic music in a kind of hypnotic, dance way.

The band has been touring quite a bit since the first album. Locally, are you an active part of a scene, or is it more like you're doing something different there and bringing that around the world?

Xavier Thomas: We're still quite unique in Kinshasa, and if we play there it would be more of a block party. Makara has a lot of dancers in his crew, and dancers would join from the youngest at the beginning [of the show] to the more experienced, bridging between classic Congolese dance and more contemporary dance. There's a lot of theater in the dance as well.

When we play there, it's still alternative. Once in a while we might play a bigger stage, but we play out [of the country] way more in front of way more people. We try not to play too often [here]. It's a huge city, so it can be tricky with the power cuts and everything. It's more of the art scene and people from the performance art school and dancers who gather if we do an event in Kinshasa, it's not huge crowds.

You've performed on some pretty big platforms, as well as at global music festivals. What goes into your energetic live performance; is there improvisation?

Xavier Thomas: It's key that we are still incredibly passionate, and we feel the music and leave a lot of space for improvisation. Then we can surprise each other, even during a gig. One track can be one length or double the next time, depending on the feeling, the crowd, the sound system and the time we play.

Usually, people end up really moving, sometimes without realizing. We don't spare any energy. You end up drenched in sweat. I think because our excitement is real, the music is not over-rehearsed. We're still always excited at every show. I think people can feel that it's not staged. There can be unexpected things happening, which keeps us energetic, motivated and surprised on stage.

How does the band usually feel after a performance? Is it a cathartic experience?

Xavier Thomas: Well, we have our kind of ceremonial thing. We usually talk together at the beginning; we gather and stick our heads together, and we say where we are and what we want to achieve. At the end of the concert, the whole hour or so feels like it's passed by really quick, and you're still left with that rhythm or energy, even though you might be super tired, sometimes traveling and playing every day. Sometimes we have more energy at the end. At the beginning, we feel tired, and then the energy really comes in, and we feel super energized and super sharp and really awake at the end. It's good for us.

What does Kinshasa sound like to you?

Xavier Thomas: For Makara and I, to explain to somebody who's never been to Kinshasa, it's a very sonic city. I've never seen [anything like it]. It's so crowded; I think it's 15 million or 18 million people now. [Editor's note: 17 million is the latest estimate.] Everybody lives on the ground floor. There aren't too many high buildings, so the density of people is very high. For this reason, it's visually a bit crowded and overwhelming with people, cars, colors and everything.

Therefore, to be noticed or stand out, everybody needs to have their own little signal or jingle. You can tell who's around you with eyes closed. A nail polish vendor would just bang two little glass polish bottles; that sound carries far away and they have their rhythm. People who sell SIM cards have a loop on their megaphone.

Sound is how to be noticed; how to sell yourself, what's your role, what's your identity. That's obviously, without talking about music and sound systems. Churches have their own huge sound systems and they can clash with the club in front. Also something very typical in Kinshasa; it goes to the fullest, to the max, everything is used at its highest potential. The sound is pushed in overdrive and distorted because you want to be louder than the next person. It's all these little sound signals that can tell exactly who's around you or sometimes where you are as well. For me, that's the sound, plus the traffic.

Wow. It must be so different going somewhere more remote, or just where it's quieter. It must feel almost like something's wrong.

Xavier Thomas: There's not many moments with silence because at night the city is still alive. People like to go out. You can have a church next to you with a full live band and a huge PA sound system at 3 a.m. Quiet moments are rare.

Makara: It's hard to deal with silence. I don't feel comfortable in silence because I've never really experienced it.

Latest News & Exclusive Videos

Behind Ryan Tedder's Hits: Stories From The Studio With OneRepublic, Beyoncé, Taylor Swift & More

Crowder Performs "Grave Robber"

NCT 127 Essential Songs: 15 Tracks You Need To Know From The K-Pop Juggernauts

5 Rising L.A. Rappers To Know: Jayson Cash, 310babii & More

Why Elliott Smith's 'Roman Candle' Is A Watershed For Lo-Fi Indie Folk

Photo: Emmanuel Oyeleke

interview

Tekno Talks New Music, Touring America & His "Elden Ring" Obsession

Ahead of his Back Outside tour, which hits the U.S. June 22, Nigerian artist Tekno details the origins of his name and sound, as well as his predictions for the future of African music on a global stage.

It takes a lot of guts to declare yourself the "King of Afro-pop," but Tekno has the hits to back it up.

The Nigerian artist is a staple of the country’s Afrobeats scene, responsible for massive hits such as "Pana" (over 66 million Spotify streams). He’s collaborated with massive artists across the world, starting in 2012 when he enlisted Davido for his breakout single "Holiday." He’s also entered the studio with the likes of Drake and Swae Lee, and Billie Eilish is a professed fan.

Despite this, Tekno hasn’t quite reached the levels of fame that colleagues WizKid and Burna Boy have stateside, but that may be about to change. He’s touring extensively across the U.S. this summer as part of his Back Outside Tour, supporting his 2023 album The More The Better. Tekno also recently inaugurated a label partnership with Mr. Eazi-owned emPawa Africa, defecting from SoundCloud.

The video for his latest single, "Wayo," features the artist as a cab driver going through relationship problems. It's a perfect example of Tekno’s classic pan-African pop, with romantic lyrics and a sweetly melodic sound.

GRAMMY.com caught up with Tekno ahead of his tour, which kicks off June 22 in Columbus, Ohio, to chat about his new music, career goals, and a surprising video game obsession.

You recently released a new single. Tell us a little bit about "Wayo?"

"Wayo" is basically me just tapping into my roots sound, the original pan-African Tekno sound. Our music has morphed and just grown into so many different sounds over the years. And it's very easy to forget that this sound existed before all this music that's playing right now. So I had to deep dive into that. That's basically how I describe "Wayo," I call it a basic Tekno love song. Like it's basically how I started really.

I don’t know if you’re aware that there’s an entire genre of music called "Techno?"

Yes, yes, it’s close to house music.

They’re pretty close. Actually, techno music was invented here in America by Black musicians in Detroit.

Oh, wow. Yeah, people don’t really listen to the techno genre out here yet. They prefer more melodic and groovy music.

So in that case, I did want to ask you about your artist name. Because if people don’t really listen to techno music in Africa, where did your name come from?

I was much younger, and I was looking for a name while I was in church. I’m a Christian, so I was looking for a name that had some form of Christianity to it, even though I knew I wanted to be a secular artist. And then I found this name, "tekno," and it's Hebrew, it means something like "God's people" or "God's word." It's spelt a little bit differently, I can't really remember. But I just liked the meaning of it, and the name stuck with me. And that's how I started calling myself "Tekno."

You've declared yourself the "King of Afro-Pop." Why do you consider yourself to be the king of Afro-pop, and why that instead of the King of Afrobeats or another label like that?

It's more of a personal thing in a way. My favorite artist of all time, forever, will always be Michael Jackson. And Michael Jackson is the King of Pop. So when I named myself the "King of Afro-Pop," it’s because I like Michael Jackson, but it's also because I'm the king of Afro-f—ing-pop. So the name just kind of has a good ring to it.

I want to talk a little bit about partnering with Mr. Eazi; why did you decide to join EmPawa? What do you think the partnership holds for your future, and for the future of music in Africa?

I just love making music so much, that's the goal for me. And I've gone from camp to camp, level to level, and after a while it just starts to wear on you. I don't want to just keep moving from Triple MG to Universal to SoundCloud; I want my own thing that’s a little more permanent. And Eazi is not just my friend, he's my brother. We've been talking about this for years, about doing business together.

There are reasons why it made so much sense for us to come together, but I don't want to share everything. But I like being a priority. If I'm on SoundCloud, I don't want to be on a list of 27 artists where I'm maybe number 18 and my music doesn't get the focus it needs. Like, say I put out a song, and everyone on SoundCloud has gone on holiday. And I'm not aware because I'm Nigerian, I don't know that this day or that day is a holiday in the States. But working with a brother and a team that is home, where we know the system and we understand the culture, it's just way, way better. Because we know ourselves, we know our culture. So working with a brother that has this amazing setup at EmPawa, it just made so much sense.

Read more: Mr. Eazi’s Gallery: How The Afrobeats Star Brought His Long-Awaited Album To Life With African Art

You've collaborated with some American artists before, and Billie Eilish said she is a big fan of yours. Is there anyone in the U.S.-UK ecosystem that you would consider a dream collaboration?

I’d definitely love to work with Billie Eilish. 100 percent. But Drake would always be my favorite collaboration, just because we've been in the studio together. We've talked about it. You know, if I start something I want to see it finished.

He's just an inspiration to the business. Drake, he makes you know that you gotta work, because as big as Drake is he works harder than everybody else. That’s not to say that I wouldn’t love to collaborate with so many other artists whose music I really love.

Are you following the beef between Drake and Kendrick at all?

That was so good, man. I didn't consider that a beef, because when I would watch boxers in the ring fight, let’s say I'm watching Mayweather vs. Pacquiao, it doesn't matter who I'm a fan of. It doesn't matter who wins, I'm entertained.

As a big fan of music, I enjoyed every Drake song and I enjoyed every single Kendrick Lamar song. But if you ask me who I prefer, I would always pick sides and choose. But was I entertained? I definitely was, for sure.

How is working with Americans different from working with Africans? What are the distinctions you find between the two?

Back in Nigeria we don't work in big studios, we work at home. Like, if I want to work with Wizkid I would probably go to his house, or he would come to mine, and we would make music there. But if I'm going to work with Travis Scott, we're gonna go to the studio. If I'm working with Billie Eilish we're gonna go to the studio.

You’re touring North America this year. Do you have any expectations, or anything you’re looking forward to?

I'm just happy to be back outside. I went through this period where I had lost my voice in 2019. And after that happened, and I went through surgery in New York, Corona[virus] happened right after.

And in this whole period, I kind of just stayed away from how much I worked and how much I put out music in the past. I feel like I got used to not being active, so I haven't necessarily been performing for a while. That’s why this tour in the U.S. is called The Back Outside Tour. Because for a long time I haven't been outside, I haven’t been performing, I’ve just been at home.

I like to game [and] I like to make music. I make so much music, but I feel like being home has kind of restricted the amount of music I put out. Because anytime I’m outside, I just get this feeling like I want to conquer the world, I want to do more; I want to put out more.

I want to do more than I've done in the past. So this tour for me is just getting back outside, just getting myself out there and just being on the road heavy. You get lazy if you stay home for too long; we’re habitual creatures. So now I have the mindset that I have to forcefully keep myself out there and just be outside. I'm gonna be touring for three months in the U.S. That's a long time.

You mentioned you’re a gamer. What have you been playing recently?

Recently I've been on "GTA V"; the online is extremely good. Just because it has this plethora of radio stations where while you're gaming you can still bask in this vast playlist. And it’s just fun because you get to play with people around the world. I [also] have this Nigerian community I play with. It's like a way to just be around the people even though I'm in the house, so it's really lovely. And "Call of Duty" is a great one too. But my all time favorite I would say is "Elden Ring." I got locked into Elden Ring for like eight weeks.

Amapiano has really become the dominant sound coming out of Africa in recent years. What do you think will be next?

Tekno sound! They miss it! My sound is like "Game of Thrones," season one to seven.

Not season eight.

Not season eight. I didn’t say that, you said that! [Laughs.]

Basically, I’m not saying amapiano isn’t beautiful music, I’m not saying Nigerians haven’t found a way to evolve it in a way that’s different from the South African type. The South African sound will always be the original one, and every time you record on a South African amapiano beat, you can just tell the difference in the sound. It’s their culture, they own it.

But we [Nigerians] are extremely good at taking your sound and putting our own flavor on it. It’s still your sound, but we play with it. So I feel like it’s been two years of the same [amapiano] and after a while people are gonna want another type of song. I’m not saying Amapiano will go away all of a sudden, it’ll never go away. But people want that pan-African sound. The local rhythm. And Tekno got that.

Learn more: 11 Women Pushing Amapiano To Global Heights: Uncle Waffles, Nkosazana Daughter, & More

Can you go into detail? How do you describe this pan-African sound?

These are songs that always tell a story, it’s never just random. "Wayo" is talking about, "If I invest in my love, would I get a return?" "I no come do wayo" means I'm not trying to play games. I'm serious. If I invest in this love, would I get it back? This thing we call love? Do you truly believe in it? Or you're just with me for the sake of dating somebody?

This type of music always has a deep rooted message in the melodies; it's not just like a regular party thing. There's always a good tale behind the sweet melodies. So like, no, no matter how new school our music goes, this type of sound would always be this type of sound. You're not taking it where. It’s culture.

The video for "Wayo" shows you driving a cab. Did you ever have to hold down a day job like that before you became a successful musician?

Oh my god. I've been a houseboy. I catered for four little kids. They were so stubborn, man, that was the hardest thing I've done in my life. [Laughs.] That would have to be a different interview. I've worked in churches, too. I grew up from a very humble background and I'm grateful to God that I experienced that.

Tems On How 'Born In The Wild' Represents Her Story Of "Survival" & Embracing Every Part Of Herself

Photo: Nick Spanos

interview

Living Legends: How Dead & Company Drummer Mickey Hart Makes Visual Art From Vibrations — And Brought It To Las Vegas' Sphere

Dead & Company are currently embarking a residency at Las Vegas' sphere, which features drummer Mickey Hart's eye-popping, unconventional art. Hart spoke to GRAMMY.com about how it came to be, and how the Grateful Dead's legacy continues to ripple forth.

Living Legends is a series that spotlights icons in music who are still going strong today. This week, we interviewed Mickey Hart, one of two drummers — along with Bill Kreutzmann — of the Grateful Dead and its contemporary offshoot, Dead & Company.

His first-ever solo art exhibition, Art at the Edge of Magic, will run through July 13 at the Venetian Resort in Las Vegas, as part of the Dead Forever Experience. His work is also incorporated into their current residency at Las Vegas' Sphere.

After decades behind a drum kit with the Grateful Dead, and now in the same role in Dead & Company, Mickey Hart has learned a truly cosmic lesson: "The basis of all of creation is vibratory."

For years, in parallel with his legacy as a music maker, he's made visual art using a sui generis method, which has plenty in common with his techniques as a drummer. Check out his visual art, which he's been creating for years in parallel with his music making; some of it may look like paintings, but that doesn't quite describe what it is.

Rather, Hart employs vibrations — much like he's done behind the kit for decades — to bring out hitherto-invisible dimensions in paint. The results are captivating to the eye — at times, otherworldly.

The strength of Hart's visual art has added another layer to the Grateful Dead cosmos. If you're in or near Las Vegas, you can check out these works as part of the Dead Forever Experience, in an exhibition at the Venetian running until mid-July.

Additionally, if you catch Dead & Company during their Sphere residency (which runs through July 13), you can immerse yourself in it during the famous "Drums/Space" portion of the set — a percussive, celestial section stretching way back in Dead setlist history.

"I just love to do it. Sometimes, your hobbies overtake you and become a necessary ingredient in your life," Hart cheerily tells GRAMMY.com. "And that's what happened with this visual medium, that it kind of grew on me and made me want to go back over and over and over again to learn the craft."

Whether or not you'll be heading to Vegas, read on for an interview with Hart about how he makes these sumptuous textures and hues truly pop — as well as his gratitude for the potency and longevity of the Dead's afterlife. (No pun intended.)

This interview has been edited for clarity.

Your visual work is beautiful. What can you tell readers about how you make it — the brass tacks?

Well, I wouldn't say I paint. I don't use brushes — sometimes, once in a while — but really it's more of a pouring medium, and a spinning medium, and so forth. But I use vibrations in the painting process, and I think that's why people call it vibrational expressionism.

I use a subwoofer and the Pythagorean monochord — a stringed instrument — drives the subwoofer. Pythagoras, of course, invented it, and it goes down very low to 15 cycles, sometimes 10 cycles. And that vibrates the paint. I mix multiple colors, and the colors come up within each other, and it reveals these details that you cannot get in any other way.

And I just kind of fell on it. In the beginning, I was drumming them — beating underneath them and so forth. But now, I've progressed to using a Meyer subwoofer, and it works just fine. And that's how the paintings are born. They're vibrated into existence.

Once I apply my mumbo jumbo to it, and using additives that create unique features — shapes, people, animals, mountain ranges, glaciers — you see all kinds of things within the paintings if you look at them, and let yourself go, and become part of the paintings.

Everybody has their own interpretation of [what they reveal], which is really important. These are not, like, a rose, or a vase, or a car. It's not that kind of art form. So, it raises your consciousness. And if you can connect with it, you get high. And that's what these things are all about. That's what art's all about. No matter what it is, audio or visual, it's consciousness raising at its best.

I take it you've been developing this ability in parallel with your work in the Dead universe for some time.

Well, of course. I work with vibrations. The vibratory world is where I live, and I make my art there. It's always been like that. I'm a lover of low end; low frequencies are my specialty. And because I'm a percussionist and many of my drums are very large and they speak to the range, the frequency, which is not normally accessed.

So, I create these works using these low-frequency creations. And that was something that I fell on years ago, but as a hobby; this was nothing more than an escape to another virtual headspace. Now, I share it with others.

I feel like this sound-based approach to visual art is a fairly unexplored space.

For sure. I mean, you can look it up. I've looked it up. And when you look up vibrational expressionism, I'm the only one that's there. Someone coined that term years ago, and it's kind of fitting.

I might be unique in that particular way, but that's the only way I know how to bring the colors up within themselves and reveal the super details.

Photo: Emily Frost

And I'm sure this process is fluid and mutable; you don't apply the same technique for every piece.

Yes, I apply different frequencies and different rhythms to different paintings. They're not the same. Every time I approach it — whether it be a canvas, or wood, or plexiglass, or glass, or whatever the surface is — it's always different. I never repeat. Every one of them is unique.

It's about the mixing of the paints, and the ingredients I put in the paint. And then you have to let it go and you jam. That's what these works are — they're jams. Sometimes, I have a thought on how I want it to be, and then sometimes it'll completely change once I put paint to canvas.

You learn over years. I've been doing this for about 25 years as a hobby, so I've got hundreds of these. And some of them never see the light of day. That's the luck of the draw, but luck favors the prepared mind, and I prepare that before I go in. I focus and concentrate on not concentrating. I just try to be there now and let the flow happen.

I improvise. That's my love. That's the only thing I really know how to do. Memorizing things and repeating is not who I am. I don't paint by the numbers. You don't need me for that.

Much like what you do on stage!

The Grateful Dead never did memorize many things. It was mostly a seat-of-the-pants kind of art form, but you learn how to become a seat-of-the-pants artist, if you will. There's adventure, there's failure, there's success, there's luck, there's chaos, there's order, and back and forth.

The duality of all of that reflects life. It gets you high too. You can look at it and all of a sudden you're in a different, virtual space. That's what art does — good art, anyway. It puts you in a place of great wonder and awe.

Photo: Emily Frost

Can you talk about using the Sphere as a canvas for your work?

That's how I look at it — as a blank canvas. When I hit the stage, I'm not thinking of anything. I prepared, I have my skill, I'm ready to go, but I'm not really thinking in the normal sense of the word. I throw that away and I just feel muscle memory, you might call it.

When you're playing music in a band, you become a groupist. You learn to be able to interrelate between six people each having their own consciousness, making something larger than the parts. Music is great at that. But in painting, it's a singular thing.

Music is just the moving of air. That's the delivery system. It's the movement of air. And in this case, it's light. It's what the light does to you. The eye is more powerful than the ear as an organ. So people really react to the visual. Hopefully in the Sphere, there's a combination of both that come together and form something much larger.

I appreciate that you view a drum as far more than simply a drum.

It's not something that just played to keep time. It's something that is an integral part of the orchestra, right up there with melody and harmony. The primacy of rhythm is something that has come into music in this century. If you listen to the radio, it's rhythmic-driven, mostly. Of course, there's the melodies, but the basis of it all is rhythmic.

Visual art is the same thing. It's all about rhythm and flow. If you don't have that, you don't really have anything. You have to have a groove.

The basis of all of creation is vibratory. These arts are just miniatures of what's happening in the cosmos. I mean, we are in the wash of these vibrations that were created 13.8 billion years ago from the singularity, the big bang, and that's still washing over us. And that's where art comes in. It connects you to the infinite universe at its best.

You guys seemed to realize early on that you could transcend simply playing rock songs in a band.

When we were younger, we were all ingesting psychoactive drugs. They certainly freed our perspective, and created a different kind of perspective when we all played together. Some of it was drug-related, you might say. We took what we could from those experiences and created a new kind of music.

That was an important part of our exploratory nature as we were falling on Grateful Dead music. We were exploring realms of consciousness that were not accessible to us normally in a normal waking state. These chemicals certainly helped in that respect, used correctly and professionally. They were an enormous, enormous help.

And now we're finding out that LSD is being used in therapeutic and medicinal and diagnostics and all of that. These are very helpful in many ways.

Photo: Emily Frost

How has it felt watching the Grateful Dead turn into a franchise, a universe? This visual element at the Sphere adds a whole new layer to it.

Well, it's very interesting to see all the corners and of the universe that the Grateful Dead spirit has reached and all the people and all the bands that copy our music. It's very rewarding and complimentary, I think.

We knew it was special. First time I ever heard it, I knew it was special. How special? You never know, but you have to keep at it being special. And eventually, it skips generations, which is what we've done — generation, after generation, after generation. The parents share with their kids, their kids, their kids.

It's something that's very friendly — hanging out with your parents at a concert like that, and having a great time together, and sharing something that they shared when they were younger.

It's fantastic. It's unbelievable that it has that power. I was just talking to someone the other night and they asked me to explain it. You can't explain it in words. You have to hear it. You have to be there. You have to feel it. You have to feel the community that it spawns, and this feeling that you get in the music. It's very seductive, if you allow yourself that moment.

I was just reading this morning that Diplo — the electronic musician, a very good musician — just became a Deadhead the other night.

Really!

Oh, yeah. It transformed him completely. You never can tell who gets touched by our music. It's something that's not explainable, but it keeps going on. The people will not let it go.

As long as people are interested in our kind of music and our kind of scene, we'll keep playing. There's no end to it until we don't have the facility to play, or the rhythm stops. I plan to do this till the day I die. There's no question about it. I've always thought that. There's no secret.

I think Bob and I both agree on that, and all of the Grateful Dead, Bill, Phil, certainly Jerry, we're all in the same boat when it comes to Grateful Dead music, the passion that we bring to it. And it's very rewarding that people enjoy it as deeply as they do.

I tell you, I can't express the gratitude that I have just being part of it. We all feel that same way. It's very humbling, to be honest with you, that it's grown to be this. It was just a little cub. Now it's a roaring lion. It's just a gigantic monster that is always meant for the good, and that's very rewarding. It's a good life to lead. We work very hard at it.

A Beginner's Guide To The Grateful Dead: 5 Ways To Get Into The Legendary Jam Band

Photo: Courtesy of Creepy Nuts

video

Global Spin: Creepy Nuts Make An Impact With An Explosive Performance Of "Bling-Bang-Bang-Born"

Japanese hip-hop duo Creepy Nuts perform their viral single "Bling-Bang-Ban-Born," which also appears as the opening track from the anime "Mashle: Magic and Muscles."

On their new Jersey club-inspired single "Bling-Bang-Bang-Born," Japanese hip-hop duo Creepy Nuts narrate the inner monologue of a confident man, unbothered by others’ negativity and the everyday pressures of life.

In this episode of Global Spin, watch Creepy Nuts deliver an electrifying performance of the track, made more lively with its bright flashing lights and changing LED backdrop.

"Before I show them my true ability/ My enemies run away without capability," they declare in Japanese on the second verse. "Raising the bar makes me very happy/ ‘Cause I’m outstanding, absolutely at No.1."

"Bling-Bang-Bang-Born" was released on January 7 via Sony Music and also serves as the season two opening track for the anime "Mashle: Magic and Muscles." The song previously went viral across social media for its accompanying "BBBB Dance."

"Basically, the song is about it’s best to be yourself, like flexing naturally. Of course, even though we put effort into writing its lyrics and music, it’s still a song that can be enjoyed without worrying about such things," they said in a press statement.

Press play on the video above to watch Creepy Nuts’ energetic performance of "Bling-Bang-Bang-Born," and don’t forget to check back to GRAMMY.com for more new episodes of Global Spin.

From Tokyo To Coachella: YOASOBI's Journey To Validate J-Pop And Vocaloid As Art Forms