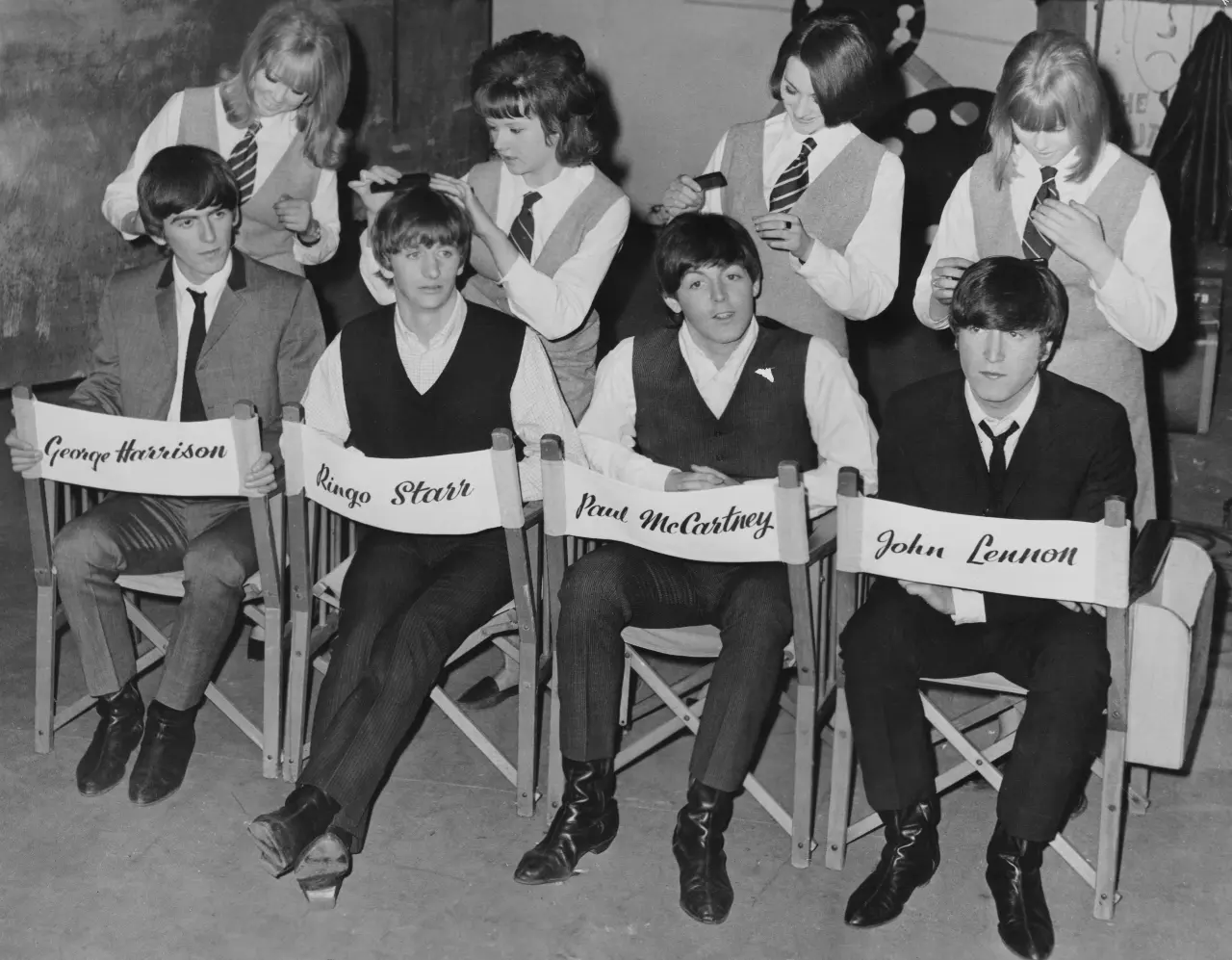

Photo: Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

feature

1962 Was The Final Year We Didn't Know The Beatles. What Kind Of World Did They Land In?

The Beatles broke out regionally in 1963 and nationally in 1964, which makes 1962 the last year they weren't widely known. And given that we'll probably never forget them, that makes it a special year indeed. What was going on then?

During the mid-to-late 1950s, the titans of rock 'n' roll dominated the earth; by 1962, many of them had seemingly gone extinct.

Buddy Holly went down, young. Little Richard found Jesus. Jerry Lee Lewis married his 13-year-old cousin and was crucified in the press. Chuck Berry spent three years in jail. Elvis, fresh out of the army, was making films often derided as beneath him. So when the Beatles broke out — regionally in 1963, and nationally the following year — they arrived in a barren, joyless world, right?

This is usually the line: In the wake of the Kennedy assassination, in a wasteland of schmaltzy, insipid crooners, the Fabs made the desert rejoice and blossom as the rose. As a gang of impudent, talented youths — a feast for the ears and eyes — with reams to give the world, they taught an unmoored and grieving America to have fun again.

Of course, that certainly applies to some Americans in those days. But if you ask Mike Pachelli, he might give you a different story. Because he was there.

"That's crazy," the guitarist, educator and YouTuber tells GRAMMY.com. And he's largely known to the world because of the Beatles; he deconstructs their songs to his almost 100,000 YouTube subscribers. But for all his reverence for the Fab Four, Pachelli describes life just before them as chock full of culture, including artists still revered as household names.

"Kids are always very industrious, and we found stuff that was cool," Pachelli adds. "It's just that when the Beatles came around it was like, 'Wow, that's a whole other kind of cool.'"

On one hand, 1962 is a very special year. It was the last in human history — a span of anywhere from 6,000 to six million years, depending on who you ask — that the Beatles wouldn't be a widely recognized thing. And save a species-ending celestial event, it's likely humanity will never forget them. This, in musical terms, makes 1962 something of a year zero, a liminal point between B.C. and A.D.

The Beatles performing at the Star Club in Hamburg in May 1962. Photo: K & K Ulf Kruger OHG/Redferns

Indeed, it's tempting to frame the Beatles as messianic — reams of ink have made their debut performance on "The Ed Sullivan Show" to reinforce that narrative. Everybody remembers "All My Loving," "She Loves You" and the rest; few remember that they were followed by a desperate-looking magician doing salt-shaker tricks. (As Rob Sheffield put it in Dreaming the Beatles: "Acrobats, jugglers, puppets — this is what people did for fun before the Beatles came along?")

Through that lens, the Beatles can look like the product of divine intervention, meant to restore brilliant hues to a monochrome culture, Wizard of Oz-style. Why not ask Tune In author Mark Lewisohn about it? He's almost universally regarded as the foremost global authority on the Fab Four. And to that point, he lists some names.

"Otis Redding, James Brown, Little Stevie Wonder, Aretha Franklin, Paul Simon, Freda Payne, Randy Newman, Ike and Tina Turner, the Supremes, Wilson Pickett, Gladys Knight, P.J. Proby, Barbara Streisand, Glen Campbell, Patti LaBelle, and Dionne Warwick" were all waiting in the wings or as established stars in 1962, he tells GRAMMY.com.

"They're all making records before the Beatles," Lewisohn continues. "So, anyone who says the Beatles fashioned the entire scene doesn't know what they're talking about." Rather, the Beatles entered an already-fecund landscape 60 years ago — and reshaped it forever.

"Humming A Song From 1962"

In the grand pop-cultural timeline, 1962 tends to represent innocence, youth and the "good old days." In his 1976 hit "Night Moves," Bob Seger awakens "to the sound of thunder," with a song from that year on his lips. (It was the Ronettes' "Be My Baby," which was actually from '63; apparently, Seger felt strongly enough about what 1962 meant to him to tweak history a tad.)

Plus, George Lucas didn't set his classic coming-of-age flick American Graffiti in 1962 for nothing.

"These kids are driving all night and they're hearing the '50s rock 'n' roll on the radio," Sheffield, who is also a Rolling Stone contributing editor, tells GRAMMY.com of the 1973 film. "They're listening to Wolfman Jack and it's kind of the last gasp of that old school rock 'n' roll era."

Sheffield cites the scene where a brooding John Milner (played by Paul Le Mat) tells the gangly, 12-year-old Carol Morrison (played by Mackenzie Phillips) to turn off "that surfing s***" on the dashboard radio — the Beach Boys' "Surfin' Safari." "Rock 'n' roll's been going downhill ever since Buddy Holly died," Milner reports, his face fallen.

American Graffiti's soundtrack is packed with hits that paint a picture of young love in Modesto, California, in 1962. Aside from '50s jukebox mainstays like Bill Haley and the Comets' "Rock Around the Clock," you've got obscurer cuts by acts like Lee Dorsey, the Cleftones, and Joey Dee and the Starlighters — all from the previous year.

If you want to understand the prevailing vibe of the year in question, American Graffiti is the first looking-glass you should peer through. For another, look no further than the Beatles' infamous audition for Decca Records — on the very first day of 1962.

"Searchin' Every Which A-Way"

The Beatles had a massive, unlikely shot on January 1, 1962, when they auditioned for Decca Records. But by most accounts, they blew it: the label ended up telling them "guitar groups are on their way out." (They ultimately went with Brian Poole and the Tremeloes.)

The Decca audition, which floats around the internet today, is famously regarded as terrible — John Lennon called it "terrible" himself a decade later. But if you listen today with fresh ears, it's really not — despite some rough moments and pre-Ringo drummer Pete Best's shaky grasp of rhythm.

It's important to note that the Beatles weren't experimenters come 1965 with Rubber Soul, or with 1966's Revolver — they were a deeply experimental band from jump. The Beatles were unique for their ability to emulate and synthesize disparate threads of 1962's musical landscape; just take a look at their Decca setlist:

Immediately notable are Lennon-McCartney originals like "Like Dreamers Do," "Hello Little Girl" and "Love of the Loved," which was unheard of — rock 'n' roll groups simply didn't write their own songs back then.

On top of that, you've got a Phil Spector ("To Know Her is to Love Her"), a showtune via Peggy Lee ("'Til There Was You"), a jolt of Detroit R&B ("Money (That's What I Want)"), comedic numbers (three Coasters songs, including "Searchin'"), a jazz standard (Dinah Washington's take on "September in the Rain") — on and on and on. All of that, plus country and western, music hall, and so many other forms, were swimming around their skulls.

"What they'd been doing in Hamburg and then brought back to Liverpool was 'We just have to do everything, because we're playing for 10 hours a night,'" Alan Light, a music journalist, author and SiriusXM host, tells GRAMMY.com. "Anything that they knew, or anything that they might know, was fair game for material, because they just had to keep going."

But the Beatles' omnivorousness in this regard, both in their choice of cover material and raw inspirations for songs, wasn't just to run the clock — it spoke to their essences as artists and human beings. "They were so receptive to anything that was good, and it didn't matter what genre it was, as it didn't matter what genre they were," Lewisohn says.

So, how do you know that music in 1962 was, in many ways, outstanding? Because without it, there'd be no raw material for the Beatles to work with.

Aside from the Beatles' purview, other fascinating musical forces were at play. According to Kenneth Womack, a leading Beatles author, what the music industry hawked in 1962 wasn't necessarily what the public asked for — hence John Milner's reaction in American Graffiti.

"What happens is you go from that pretty intense rock era to the crooners and doo-woppers coming back with a vengeance," Womack tells GRAMMY.com. "That was really not music that people wanted. It was music that was marketed to us."

Still, many tunes from 1962 and thereabouts endure — including all the tremendous, often Black, talent Lewisohn mentions above, as well as a smattering of bubblegum songs that have baked themselves into 21st-century life.

That year, Shelley Fabares released her confectionary cover of "Johnny Angel," and Chubby Checker's "Let's Twist Again" won a GRAMMY for Best Rock 'n' Roll Recording. The Tokens’ "The Lion Sleeps Tonight" became a No. 1 hit; so did Gene Chandler's "Duke of Earl." ("There's still a pulse around the old-world stuff," Light notes about the latter tune. "It's not gone.")

Plus, recent years had given us "Itsie Bitsie Teeny Weeny Yellow Polkadot Bikini" and "The Purple People Eater" — further proof of novelty songs' enduring presence.

"It's funny that the song from 1962 we hear the most nowadays might be 'Monster Mash,' which has just turned into such a seasonal banger," Sheffield says. "If you went back to a music fan in 1962 and said, 'Sixty years in the future, the most famous song from this era is going to be 'Monster Mash,' people would laugh in your face."

"You've got a lot of the trivial pop throwaways that the people laugh about, but a lot of those were fantastic songs," he continues, citing rock 'n' roll singer Freddy Cannon's "Palisades Park" as a "fan-f***ing-tastic song": "The drummer on that song is absolutely insane. That's the year that Stax starts to make its mark nationwide."

On top of that, you've got Spector, Motown, Chicago soul, Memphis instrumental R&B (hello, Booker T. and the MGs' "Green Onions"), the still-green Beach Boys and Bob Dylan… the list goes on. To say nothing of Ray Charles, whose Modern Sounds in Country and Western Music — released in 1962 — remains a monumental fusion of Black and white cultures.

1962 was also a major year in American culture: John Glenn became the first man to orbit the Earth, the Cuban Missile Crisis erupted, and it was the only full year John F. Kennedy was president. The Space Needle and the first Wal-Mart were opened. Marilyn Monroe sang "Happy Birthday" to JFK and died three months later.

The demolished Star Club in 1987. Photo: Günter Zint/K & K Ulf Kruger OHG/Redferns

In British media at the very least, there was a shift toward irreverence that left an opening for the flippant and cheeky Fabs. "The Beatles came up at the very same time when you could be less respectful to the sacred cows of society," Lewisohn says, noting a rising acceptance of unfettered working-classness, like in the pre-"Sanford and Son" show in the UK, "Steptoe and Son."

Sheffield stresses the impact of the draft on the world the Beatles entered: "I think they presented to American youth a vision of adult male life that wasn't military-based or violence-based," he says. And across the pond, the abolition of conscription in the UK in 1959 had fundamentally shaped the Beatles' path.

"They were clearly not boys who had been in the war," Lewisohn says. "The Beatles escaped it in the very nick of time."

What If The Beatles Never Broke Through?

As most parties agree, one of the weirdest things about the Beatles is that they happened at all — which is easy to overlook due to their sheer omnipresence.

"For me, the weirdest things about the Beatles are the most obvious things about the Beatles. Just the four of them being born in this town and finding each other and making music together," Sheffield says. "It's so shocking and bizarre that that synchronicity happened and that they were as good as they were, and they were able to keep inspiring and challenging and goading and competing with each other, and that they were able to scale those heights."

"I mean, there's nothing in world culture that's anything like a precedent for this," he continues. "And they were able to do it for 10 years, which is about 30 times longer than anybody would have predicted in 1962. That in itself is so completely bizarre."

Not that anyone could be a prognosticator — but if the Beatles had never been born, or broke up when they began, what would the '60s be like? Obviously, the Vietnam War and subsequent youth revolt would happen. Humanity would land on the moon.

But the music world, including all their peers, would be radically different. Without them, the Stones would probably never have written songs, or had their manager. The Beach Boys wouldn't have been spurred to make Pet Sounds or "Good Vibrations." The Byrds wouldn't use a 12-string Rickenbacker (Roger McGuinn got it from A Hard Day's Night), nor spell their name with a y. Bob Dylan may have never broken out of the folk scene.

Without the Beatles, the template of a self-contained band — a democratic gang with a unified message, lobbing working-class Britishness into the world, raining down heartening music and blistering humor, and reinventing themselves seven or eight times before drawing the blueprint for band breakups — would be gone.

"I feel like rock 'n' roll would've come back," Colin Fleming, who writes articles and books about the Beatles, tells GRAMMY.com. "It's almost like someone's on the injured list on the baseball team."

But everything played out how it did — and what unending pleasure and edification. Still, history screams that the decade would have remained semi-recognizable without the Beatles.

The '60s would still be action-packed, just in a different way; it contained all the nascent threads and forces to be so. In 1962, you had the debuts of James Bond, Spider-Man and "The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson." Anthony Burgess's A Clockwork Orange was published. Lawrence of Arabia opened in cinemas. America's presence in Vietnam dramatically escalated.

"The more I thought about it, October of '62 is interesting," Jordan Runtagh, an executive producer and host at iHeartMedia, tells GRAMMY.com. "That's the month that 'Love Me Do' came out. On the same day, Dr. No came out. It's the same month that Edward Albee's Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? came out, which completely revolutionized the theater."

It's easy to consider the '60s without the Beatles as unthinkable. But even as a diehard fan, the thought is actually strangely beautiful.

The Real Ambassadors At 60: What Dave Brubeck, Iola Brubeck & Louis Armstrong's Obscure Co-Creation Teaches Us About The Cold War, Racial Equality & God

.jpg)

Photo: Yoko Ono

list

5 Reasons John Lennon's 'Mind Games' Is Worth Another Shot

John Lennon's 1973 solo album 'Mind Games' never quite got its flowers, aside from its hit title track. A spectacular 2024 remix and expansion is bound to amend its so-so reputation.

As the train of Beatles remixes and expansions — solo or otherwise — chugs along, a fair question might come to mind: why John Lennon's Mind Games, and why now?

When you consider some agreed-upon classics — George Harrison's Living in the Material World, Ringo Starr's Ringo — it might seem like it skipped the line. Historically, fans and critics have rarely made much of Mind Games, mostly viewing it as an album-length shell for its totemic title track.

The 2020 best-of Lennon compilation Gimme Some Truth: The Ultimate Mixes featured "Mind Games," "Out the Blue," and "I Know (I Know)," which is about right — even in fanatical Lennon circles, few other Mind Games tracks get much shine. It's hard to imagine anyone reaching for it instead of Plastic Ono Band, or Imagine, or even the controversial, semi-outrageous Some Time in New York City.

Granted, these largely aren't A-tier Lennon songs — but still, the album's tepid reputation has little to do with the material. The original Mind Games mix is, to put it charitably, muddy — partly due to Lennon's insecurity about his voice, partly just due to that era of recordmaking.

The fourth-best Picasso is obviously still worth viewing. But not with an inch of grime on your glasses.

The Standard Deluxe Edition. Photo courtesy of Universal Music Group

That's all changed with Mind Games: The Ultimate Collection — a fairly gobsmacking makeover of the original album, out July 12. Turns out giving it this treatment was an excellent, long-overdue idea — and producer Sean Ono Lennon, remixers Rob Stevens, Sam Gannon and Paul Hicks were the best men for the job. Outtakes and deconstructed "Elemental" and "Elements" mixes round out the boxed set.

It's not that Mind Games: The Ultimate Collection reveals some sort of masterpiece. The album's still uneven; it was bashed out at New York's Record Plant in a week, and it shows. But that's been revealed to not be its downfall, but its intrinsic charm. As you sift through the expanded collection, consider these reasons you should give Mind Games another shot.

The Songs Are Better Than You Remember

Will deep cuts like "Intuition" or "Meat City" necessarily make your summer playlist? Your mileage may vary. However, a solid handful of songs you may have written off due to murky sonics are excellent Lennon.

With a proper mix, "Aisumasen (I'm Sorry)" absolutely soars — it's Lennon's slow-burning, Smokey Robinson-style mea culpa to Yoko Ono. "Bring On the Lucie (Freda Peeple)" has a rickety, communal "Give Peace a Chance" energy — and in some ways, it's a stronger song than that pacifist classic.

And on side 2, the mellow, ruminative "I Know (I Know)" and "You Are Here" sparkle — especially the almost Mazzy Star-like latter tune, with pedal steel guitarist "Sneaky" Pete Kleinow (of Flying Burrito Brothers fame) providing abundant atmosphere.

And, of course, the agreed-upon cuts are even better: "Mind Games" sounds more celestial than ever. And the gorgeous, cathartic "Out the Blue" — led by David Spinozza's classical-style playing, with his old pal Paul McCartney rubbing off on the melody — could and should lead any best-of list.

The Performances Are Killer

Part of the fun of Mind Games: The Ultimate Collection is realizing how great its performances are. They're not simply studio wrapping paper; they capture 1970s New York's finest session cats at full tilt.

Those were: Kleinow, Spinozza, keyboardist Ken Ascher, bassist Gordon Edwards, drummer Jim Keltner (sometimes along with Rick Marotta), saxophonist Michael Brecker, and backing vocalists Something Different.

All are blue-chip; the hand-in-glove rhythm section of Edwards and Keltner is especially captivating. (Just listen to Edwards' spectacular use of silence, as he funkily weaves through that title track.)

The hardcover book included in Mind Games: The Ultimate Collection is replete with the musicians' fly-on-the-wall stories from that week at the Record Plant.

"You can hear how much we're all enjoying playing together in those mixes," Keltner says in the book, praising Spinozza and Gordon. "If you're hearing John Lennon's voice in your headphones and the great Kenny Ascher playing John's chords on the keys, there's just no question of where you're going and how you're going to get there."

It Captures A Fascinating Moment In Time

"Mind Games to me was like an interim record between being a manic political lunatic to back to being a musician again," Lennon stated, according to the book. "It's a political album or an introspective album. Someone told me it was like Imagine with balls, which I liked a lot."

This creative transition reflects the upheaval in Lennon's life at the time. He no longer had Phil Spector to produce; Mind Games was his first self-production. He was struggling to stay in the country, while Nixon wanted him and his message firmly out.

Plus, Lennon recorded it a few months before his 18-month separation from Ono began — the mythologized "Lost Weekend" that was actually a creatively flourishing time. All of this gives the exhaustive Mind Games: The Ultimate Collection historical weight, on top of listening pleasure.

"[It's important to] get as complete a revealing of it as possible," Stevens, who handled the Raw Studio Mixes, tells GRAMMY.com. "Because nobody's going to be able to do it in 30 years."

John Lennon and Yoko Ono in Central Park, 1973. Photo: Bob Gruen

Moments Of Inspired Weirdness Abound

Four seconds of silence titled the "Nutopian International Anthem." A messy slab of blues rock with refrains of "Fingerlickin', chicken-pickin'" and "Chickin-suckin', mother-truckin'." The country-fried "Tight A$," basically one long double entendre.

To put it simply, you can't find such heavy concentrates of Lennonesque nuttiness on more commercial works like Imagine. Sometimes the outliers get under your skin just the same.

It's Never Sounded Better

"It's a little harsh, a little compressed," Stevens says of the original 1973 mix. "The sound's a little bit off-putting, so maybe you dismiss listening to it, in a different head. Which is why the record might not have gotten its due back then."

As such, in 2024 it's revelatory to hear Edwards' basslines so plump, Keltner's kick so defined, Ascher's lines so crystalline. When Spinozza rips into that "Aisumasen" solo, it absolutely penetrates. And, as always with these Lennon remixes, the man's voice is prioritized, and placed front and center. It doesn't dispose of the effects Lennon insecurely desired; it clarifies them.

"I get so enthusiastic," Ascher says about listening to Mind Games: The Ultimate Collection. "I say, 'Well, that could have been a hit. This could have been a hit. No, this one could have been a hit, this one." Yes is the answer.

Photo: Archive Photos/Getty Images

list

'A Hard Day's Night' Turns 60: 6 Things You Can Thank The Beatles Film & Soundtrack For

This week in 1964, the Beatles changed the world with their iconic debut film, and its fresh, exuberant soundtrack. If you like music videos, folk-rock and the song "Layla," thank 'A Hard Day's Night.'

Throughout his ongoing Got Back tour, Paul McCartney has reliably opened with "Can't Buy Me Love."

It's not the Beatles' deepest song, nor their most beloved hit — though a hit it was. But its zippy, rollicking exuberance still shines brightly; like the rest of the oldies on his setlist, the 82-year-old launches into it in its original key. For two minutes and change, we're plunged back into 1964 — and all the humor, melody, friendship and fun the Beatles bestowed with A Hard Day's Night.

This week in 1964 — at the zenith of Beatlemania, after their seismic appearance on "The Ed Sullivan Show" — the planet received Richard Lester's silly, surreal and innovative film of that name. Days after, its classic soundtrack dropped — a volley of uber-catchy bangers and philosophical ballads, and the only Beatles LP to solely feature Lennon-McCartney songs.

As with almost everything Beatles, the impact of the film and album have been etched in stone. But considering the breadth of pop culture history in its wake, Fab disciples can always use a reminder. Here are six things that wouldn't be the same without A Hard Day's Night.

All Music Videos, Forever

Right from that starting gun of an opening chord, A Hard Day's Night's camerawork alone — black and white, inspired by French New Wave and British kitchen sink dramas — pioneers everything from British spy thrillers to "The Monkees."

Across the film's 87 minutes, you're viscerally dragged into the action; you tumble through the cityscapes right along with John, Paul, George, and Ringo. Not to mention the entire music video revolution; techniques we think of as stock were brand-new here.

According to Roger Ebert: "Today when we watch TV and see quick cutting, hand-held cameras, interviews conducted on the run with moving targets, quickly intercut snatches of dialogue, music under documentary action and all the other trademarks of the modern style, we are looking at the children of A Hard Day's Night."

Emergent Folk-Rock

George Harrison's 12-string Rickenbacker didn't just lend itself to a jangly undercurrent on the A Hard Day's Night songs; the shots of Harrison playing it galvanized Roger McGuinn to pick up the futuristic instrument — and via the Byrds, give the folk canon a welcome jolt of electricity.

Entire reams of alternative rock, post-punk, power pop, indie rock, and more would follow — and if any of those mean anything to you, partly thank Lester for casting a spotlight on that Rick.

The Ultimate Love Triangle Jam

From the Byrds' "Triad" to Leonard Cohen's "Famous Blue Raincoat," music history is replete with odes to love triangles.

But none are as desperate, as mannish, as garment-rending, as Derek and the Dominoes' "Layla," where Eric Clapton lays bare his affections for his friend Harrison's wife, Pattie Boyd. Where did Harrison meet her? Why, on the set of A Hard Day's Night, where she was cast as a schoolgirl.

Debates, Debates, Debates

Say, what is that famous, clamorous opening chord of A Hard Day's Night's title track? Turns out YouTube's still trying to suss that one out.

"It is F with a G on top, but you'll have to ask Paul about the bass note to get the proper story," Harrison told an online chat in 2001 — the last year of his life.

A Certain Strain Of Loopy Humor

No wonder Harrison got in with Monty Python later in life: the effortlessly witty lads were born to play these roles — mostly a tumble of non sequiturs, one-liners and daffy retorts. (They were all brought up on the Goons, after all.) When A Hard Day's Night codified their Liverpudlian slant on everything, everyone from the Pythons to Tim and Eric received their blueprint.

The Legitimacy Of The Rock Flick

What did rock 'n' roll contribute to the film canon before the Beatles? A stream of lightweight Elvis flicks? Granted, the Beatles would churn out a few headscratchers in its wake — Magical Mystery Tour, anyone? — but A Hard Day's Night remains a game-changer for guitar boys on screen.

The best part? The Beatles would go on to change the game again, and again, and again, in so many ways. Don't say they didn't warn you — as you revisit the iconic A Hard Day's Night.

Explore The World Of The Beatles

.webp)

5 Reasons John Lennon's 'Mind Games' Is Worth Another Shot

'A Hard Day's Night' Turns 60: 6 Things You Can Thank The Beatles Film & Soundtrack For

6 Things We Learned From Disney+'s 'The Beach Boys' Documentary

5 Lesser Known Facts About The Beatles' 'Let It Be' Era: Watch The Restored 1970 Film

Catching Up With Sean Ono Lennon: His New Album 'Asterisms,' 'War Is Over!' Short & Shouting Out Yoko At The Oscars

Photo: Michael Putland/Getty Images

list

Wings Release 'One Hand Clapping': How To Get Into Paul McCartney's Legendary Post-Beatles Band

After 50 years on the shelf, Wings' raw and intimate live-in-the-studio album is finally here. Use it as a springboard to discover Paul McCartney's '70s band's entire catalog — here's a roadmap through it all.

Whether it be "Band on the Run" or "Jet" or "My Love," chances are you've heard a Wings song at least once — in all their polished, '70s-arena-sized glory. More than four decades after they disbanded in 1981, we're getting a helping of raw, uncut Wings.

Last February, Wings' classic 1973 album Band on the Run got the 50th anniversary treatment, with a disc of "underdubbed" remixes, allowing Paul McCartney, spouse and keyboardist Linda McCartney, and guitarist Denny Laine to be heard stripped back, with added clarity.

After a few months to digest that, it was time to reveal a session that, for ages, fans had been clamoring for. On June 14, in came One Hand Clapping, a live-in-the-studio set from August 1974 that captured Wings at the zenith of their powers.

Back then, Wings had the wind in their sails, with a reconstituted lineup Band on the Run at the top of the charts. They opted to plug in at Abbey Road Studios with cameras rolling, and record a live studio album with an attendant documentary. The film wouldn’t come out until a 2010 reissue of Band on the Run; the music’s popped up on bootlegs, but had never been released in full.

That long absence is a shame; while One Hand Clapping is a bit of a historical footnote, it absolutely rips; Giles Martin shining up the mixes certainly helped. Epochal Macca ballads, like "Maybe I'm Amazed" and "Blackbird," are well represented, but when Wings rock out, as on "Jet," "Nineteen Hundred and Eighty Five," and "deep cut "Soily," they tear the roof off.

Basically, in range and sequencing, One Hand Clapping shows McCartney prepping Wings like a rocket; soon, it'd rip through the live circuit. If you've never taken a spin through McCartney's post-Fabs discography, though, you may not know where to go from here.

So, for neophytes (or just fans wanting a refresher), here's a framework through which to sift through the Wings discography — with One Hand Clapping still ringing in your ears.

The Essentials

Remember, as you get into Wings: don't cordon off their catalog from McCartney's solo work as a whole. In other words: if you haven't heard masterpieces like 1971's Ram yet, don't go scrounging through Back to the Egg deep cuts yet: check all that stuff out, then return to this list.

That being established: the proper Wings entryway is almost unquestionably Band on the Run. Like Sgt. Pepper's and Abbey Road before it, it's an exhilarating melodic and stylistic rush, a sonic adventure — whether you go for the original or the "underdubbed" version.

In the grand scheme of solo Beatles, Band on the Run is also the one McCartney album that slugs it out with John Lennon's Plastic Ono Band and George Harrison's All Things Must Pass, in terms of artistic realization.

That being said: despite slightly inferior contemporaneous reviews, its follow-up, 1975's Venus and Mars, is almost as good — and if grandiosity isn't your bag, you might actually enjoy it more than Band on the Run. (Think of Harrison following up All Things with the sparser, more spacious Living in the Material World, and you'll get the picture.)

Between those two albums, you've got a wealth of indispensable Macca songs — "Jet," "Let Me Roll It," "Nineteen Hundred and Eighty Five," "Rock Show," "You Gave Me the Answer" — as well as satisfying deep cuts, like doomed Wingsman Jimmy McCulloch's "Medicine Jar."

From there, it's time to understand Weird Wings — which rewinds the clock to their beginnings.

The Weirdness

As the McCartney canon goes, Ram's stock seems to shoot up every year, single handedly inspiring new generations of psych-pop weirdos. By comparison, Wings' debut, Wild Life, was critically savaged in 1971, and its reputation isn't much better today.

As you'll learn so often in your solo Macca voyage — you've just got to ignore the critics sometimes. Even McCartney himself said "Bip Bop" "just goes nowhere" and "I cringe every time I hear it." What he leaves out it's a maddening earworm — to hear this loony, circuitous little sketch once is to carry it to your deathbed.

Indeed, Wild Life is full of moments that will stick with you. In the title track, McCartney screams about the zoo like his hair's on fire; "I Am Your Singer" is a swaying dialogue between Paul and Linda; "Dear Friend" is one of McCartney's most moving songs about Lennon.

Wild Life's follow-up, Red Rose Speedway, is a little more candy-coated and commercial — but outside of the polarizing hit "My Love," it has some integral McCartney tunes, like "Little Lamb Dragonfly" and "Single Pigeon."

In the end, though, Wild Life is arguably the early Wings offering that will really stick to your ribs. It's not a crummy follow-up to Ram, but an intriguing off-ramp from its harebrained universe — and as the opening statement from McCartney's post-Beatles vehicle, worth investigating just on that merit.

The Deep Cuts

McCartney has always been a hit-or-miss solo artist by design — digging through the half-written pastiches and questionable experiments is part of the deal.

1976's Wings at the Speed of Sound features a key track in the irrepressibly jaunty "Let 'Em In," and an (in)famous disco-spangled hit in "Silly Love Songs." From there, with tunes like "Cook of the House" and "Warm and Beautiful," your mileage may vary wildly.

The ratio holds for 1978's London Town: you could put the gorgeous "I'm Carrying" on your playlist and scrap the rest, or you can go spelunking. And McCartney being McCartney, despite 1979's Back to the Egg being choppy waters, he nailed it at least once — on the lithe, sophisticated, Stevie Wonder-like "Arrow Through Me."

Today, at 81, McCartney is an 18-time GRAMMY winner and an enormous concert draw — charging through his six-decade catalog in stadiums the world over. These albums only comprise one decade in his history, where he flourished as a mulleted stadium act alongside his keyboarding wife. But his catalog would be so much different if he never got his Wings.

5 Lesser Known Facts About The Beatles' Let It Be Era: Watch The Restored 1970 Film

Photo: Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

list

6 Things We Learned From Disney+'s 'The Beach Boys' Documentary

From Brian Wilson's obsession with "Be My Baby" and the Wall Of Sound, to the group's complicated relationship with Murry Wilson and Dennis Wilson's life in the counterculture, 'The Beach Boys' is rife with insights from the group's first 15 years.

It may seem like there's little sand left to sift through, but a new Disney+ documentary proves that there is an endless summer's worth of Beach Boys stories to uncover.

While the legendary group is so woven into the fabric of American culture that it’s easy to forget just how innovative they were, a recently-released documentary aims to remind. The Beach Boys uses a deft combination of archival footage and contemporary interviews to introduce a new generation of fans to the band.

The documentary focuses narrowly on the first 15 years of the Beach Boys’ career, and emphasizes what a family affair it was. Opening the film is a flurry of comments about "a certain family blend" of voices, comparing the band to "a fellowship," and crediting the band’s success directly to having been a family. The frame is apt, considering that the first lineup consisted of Wilson brothers Brian, Dennis, and Carl, their cousin Mike Love, and high school friend Al Jardine, and their first manager was the Wilsons’ father, Murry.

All surviving band members are interviewed, though a very frail Brian Wilson — who was placed under a conservatorship following the January death of his wife Melinda — appears primarily in archival footage. Additional perspective comes via musicians and producers including Ryan Tedder, Janelle Monáe, Lindsey Buckingham, and Don Was, and USC Vice Provost for the Arts Josh Kun.

Thanks to the film’s tight focus and breadth of interviewees, it includes memorable takeaways for both longtime fans and ones this documentary will create. Read on for five takeaways from Disney+'s The Beach Boys.

Family Is A Double-Edged Sword

For all the warm, tight-knit imagery of the Beach Boys as a family band, there was an awful lot of darkness at the heart of their sunny sound, and most of the responsibility for that lies with Wilson family patriarch Murry Wilson. Having written a few modest hits in the late 1930s, Murry had talent and a good ear, and he considered himself a largely thwarted genius.

When Brian, Dennis, and Carl formed the Beach Boys with their cousin Mike Love and friend Al Jardine, Murry came aboard as the band’s manager. In many respects, he was capable; his dogged work ethic and fierce protectiveness helped shepherd the group to increasingly high profile successes. He masterminded the extended Wilson family call-in campaign to a local radio station, pushing the Beach Boys’ first single "Surfin’" to become the most popular song in Los Angeles. He relentlessly shopped their demos to music labels, eventually landing them a contract at Capitol Records. He supported the band’s strong preference to record at Western Recordings rather than Capitol Records’ own in-house studio, and was an excellent promoter.

Murry Wilson was also extremely controlling, fining the band when they made mistakes or swore, and "was miserable most of the time," according to his wife Audree.

Footage from earlier interviews with Carl and Dennis, and contemporary comments from Mike Love make it clear that Murry was emotionally and physically abusive to his sons throughout their childhoods. He even sold off the Beach Boys’ songwriting catalog without consulting co-owner Brian, a moment that Brian’s ex-wife Marilyn says he felt so keenly that he took to his bed and didn’t get up for three days.

Murry Wilson was at best a very complicated figure, both professionally jealous of his own children to a toxic degree and devoted to ensuring their success.

"Be My Baby" and The Wrecking Crew Changed Brian Wilson’s Life

"Be My Baby," which Phil Spector had produced for the Ronettes in 1963, launched the girl group to immediate iconic status. The song also proved life-changing for Brian. On first hearing the song, "it spoke to my soul," and Brian threw himself into learning how Spector created his massive, lush Wall of Sound. Spector’s approach taught Brian that production was a meaningful art that creates an "overall sound, what [the listeners] are going to hear and experience in two and a half minutes."

By working with The Wrecking Crew — a truly motley bunch of experienced, freewheeling musicians who played on Spector’s records and were over a decade older than the Beach Boys — Brian’s artistic sensibility quickly emerged. According to drummer Hal Blaine and bassist Carol Kaye, Brian not knowing what he didn’t know gave him the freedom and imagination to create sounds that were completely new and innovative.

Friendly Rivalries With Phil Spector & The Beatles Yielded Amazing Pop Music

According to popular myth, the Beach Boys and the Beatles saw each other exclusively as almost bitter rivals for the ears, hearts, and disposable income of their fans. The truth is more nuanced: after the initial shock of the British Invasion wore off, the two groups developed and maintained a very productive, admiration-based competition, each band pushing the other to sonic greatness.

Cultural historian and academic Josh Kun reframes the relationship between the two bands as a "transatlantic collaboration," and asks, "If they hadn’t had each other, would they have become what they became?" Could they have made the historic musical leaps that we now take for granted?

Read more: 10 Memorable Oddities By The Beach Boys: Songs About Root Beer, Raising Babies & Ecological Collapse

The release of Rubber Soul left Brian Wilson thunderstruck. The unexpected sitar on "Norwegian Wood," the increasingly mature, personal songwriting, all of it was so fresh that "I flipped!" and immediately wanted to record "a thematic album, a collection of folk songs."

Brian found life on the road soul-crushing and terrifying, and was much more content to stay home composing, writing, and producing. With the touring band out on the road, and with a creative fire lit under him by both the Beatles and Phil Spector’s Wall of Sound, he had time to develop into a wildly creative, exacting, and celebrated producer, an experience that yielded the 1966 masterpiece, Pet Sounds.

Pet Sounds Took 44 Years To Go Platinum

You read that right: Pet Sounds was a flop in the U.S. upon its release. Even after hearing radio-ready tracks like "Wouldn’t It Be Nice?" and "Sloop John B" and the ravishing "God Only Knows," Capitol Records thought the album had minimal commercial potential and didn’t give it the promotional push the band were expecting. Fans in the United Kingdom embraced it, however, and the votes of confidence from British fans — including Keith Moon, John Lennon, and Paul McCartney — buoyed both sales and the Beach Boys’ spirits.

In fact, Lennon and McCartney credited Pet Sounds with giving them a target to hit when they went into the studio to record the Beatles’ own next sonically groundbreaking album, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. As veteran producer and documentary talking head Don Was puts it, Brian Wilson was a true pioneer, incorporating "textures nobody had ever put into pop music before." The friendly rivalry continued as the Beatles realized that they needed to step up their game once more.

Read more: Masterful Remixer Giles Martin On The Beach Boys' 'Pet Sounds,' The Beatles, Paul McCartney

Meanwhile, Capitol Records released and vigorously promoted a best-of album full of the Beach Boys’ early hits, Best Of The Beach Boys. The collection of sun-drenched, peppy tunes was a hit, but was also very out of step with the cultural and political shifts bubbling up through the anti-war and civil rights movements of the era. Thanks in part to later critical re-appraisals and being publicly embraced by musicians as varied as Questlove and Stereolab, Pet Sounds eventually reached platinum status in April 2000, 44 years after its initial release.

Dennis Wilson Was The Only Truly Beachy Beach Boy

Although the Beach Boys first made a name for themselves as purveyors of "the California sound" by singing almost exclusively about beaches, girls, and surfing, the only member of the band who really liked the beach was drummer Dennis Wilson.

Al Jardine ruefully recalls that "the first thing I did was lose my board — I nearly drowned" on a gorgeous day at Manhattan beach. Dennis was an actual surfer whose tanned, blonde good looks and slightly rebellious edge made him the instant sex symbol of the group. In 1967, when Brian’s depression was the deepest and he relinquished in-studio control of the band, Dennis flourished musically and lyrically. Carl Wilson, who had emerged as a very capable producer in Brian’s absence, described Dennis as evolving artistically "really quite amazingly…it just blew us away."

Dennis was also the only Beach Boy who participated meaningfully in the counterculture of the late 1960s, a movement the band largely sat out of, largely to the detriment of their image. He introduced the band to Transcendental Meditation — a practice Mike Love maintains to this day — and was a figure in the Sunset Strip and Laurel Canyon music scenes. Unfortunately, he also became acquainted with and introduced his bandmates to Charles Manson. Manson’s true goal was rock stardom; masterminding the gruesome mass murders that his followers perpetrated in 1969 was a vengeful outgrowth of his thwarted ambition.

The Beach Boys did record and release a reworked version of one of Manson’s songs, "Never Learn Not To Love" as a B-side in 1968. Love says that having introduced Manson to producer Terry Melcher, who firmly rebuffed the would-be musician, "weighed on Dennis pretty heavily," and while Jardine emphatically and truthfully says "it wasn’t his fault," it’s easy to imagine those events driving some of the self-destructive alcohol and drug abuse that marked Dennis’ later years.

The Journey From Obscurity To Perennially Popular Heritage Act

The final minutes of The Beach Boys can be summed up as "if all else fails commercially, release a double album of beloved greatest hits." The 1970s were a very fruitful time for the band creatively, as they invited funk specialists Blondie Chaplin and Ricky Fataar to join the band and relocated to the Netherlands to pursue a harder, more far-out sound. Although the band were proud of the lush, singer/songwriter material they were recording, the albums of this era were sales disappointments and represented a continuing slide into uncoolness and obscurity.

Read more: Brian Wilson Is A Once-In-A-Lifetime Creative Genius. But The Beach Boys Are More Than Just Him.

Once again, Capitol Records turned to the band’s early material to boost sales. The 1974 double-album compilation Endless Summer, comprised of hits from 1962-1965, went triple platinum, relaunching The Beach Boys as a successful heritage touring act. A new generation of fans — "8 to 80," as the band put it — flocked to their bright harmonies and upbeat tempos, as seen in the final moments of the documentary when the Beach Boys played to a crowd of over 500,000 fans on July 4, 1980.

While taking their place as America’s Band didn’t do much to make them cool, it did ensure one more wave of chart success with 1988’s No. 1 hit "Kokomo" and ultimately led to broader appreciation for Pet Sounds and its sibling experimental albums like Smiley Smile. That wave of popularity has proven remarkably durable; after all, they’ve ridden it to a documentary for Disney+ nearly 45 years later.

Listen: 50 Essential Songs By The Beach Boys Ahead Of "A GRAMMY Salute" To America's Band