Photo: Lionel Hahn/Getty Images

interview

Catching Up With Sean Ono Lennon: His New Album 'Asterisms,' 'War Is Over!' Short & Shouting Out Yoko At The Oscars

Sean Ono Lennon is having a busy year, complete with a new instrumental album, 'Asterisms,' and an Oscar-winning short film, 'War is Over!' The multidisciplinary artist discusses his multitude of creative processes.

Marketing himself as a solo musician is a little excruciating for Sean Ono Lennon. It might be for you, too, if you had globally renowned parents. Despite his musical triumphs over the years, Lennon is reticent to join the solo artist racket.

Which made a certain moment at the 2024 Oscars absolutely floor him: Someone walked up to Lennon and told him "Dead Meat," from his last solo album, 2006's Friendly Fire, was his favorite song ever. Not just on the album, or by Lennon. Ever.

"I was so shocked. I wanted to say something nice to him, because it was so amazing for someone to say that," Lennon tells GRAMMY.com. "But it was too late anyway." (Thankfully, after he tweeted about that out-of-nowhere moment, the complimenter connected with him.)

It's a nice glimmer of past Lennon, one who straightforwardly walked in his father's shoes. But what's transpired since 2006 is far more interesting than any Beatle mini-me.

Creatively, Lennon has a million irons in the fire — with the bands the Ghost of a Saber Tooth Tiger, the Claypool Lennon Delirium, his mom's Plastic Ono Band, and beyond.

And in 2024, two projects have taken center stage. In February, he delivered his album Asterisms, a genreless instrumental project with a murderer's row of musicians in John Zorn's orbit, released on Zorn's storied experimental label Tzadik Records. Then just a few weeks later, his 2023 short film War is Over! — for which he co-wrote the original story, and is inspired by John Lennon and Yoko Ono's timeless peace anthem "Happy Xmas (War Is Over)" — won an Oscar for Best Animated Short Film.

On the heels of the latter, Lennon sat down with GRAMMY.com to offer insights on both projects, and how they each contributed to "really exciting" creative liberation.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

You shouted out your mom at the Oscars a couple of months back. How'd that feel?

Well, honestly, it felt really cosmic that it was Mother's Day [in the UK]. So I just kind of presented as a gift to her. It felt really good. It felt like the stars were aligning in many ways, because she was watching. It was a very sweet moment for me.

What was the extent of your involvement with the War Is Over! short?

Universal Music had talked to me about maybe coming up with a music video idea. I had been trying to develop a music video for a while, and I didn't like any of the concepts; it just felt boring to me.

The idea of watching a song that everyone listens to already, every year, with some new visual accompaniment — it didn't feel that interesting. So, I thought it'd be better to do a short film that kind of exemplifies the meaning of the song, because then, it would be something new and interesting to watch.

That's when I called my friend Adam Gates, who works at Pixar. I was asking him if he had any ideas for animators, or whatever. I knew Adam because he had a band called Beanpole. [All My Kin] was a record he made years ago with his friends, and never came out. It's this incredible record, so I actually put it out on my label, Chimera Music.

But Adam couldn't really help me with the film, because he's still contractually with Pixar, and they have a lot of work to do. But he introduced me to his friend Dave Mullins, who's the director. He had just left Pixar to start a new production company. He could do it, because he was independent, freelance.

Dave and I had a meeting. In that first meeting, we were bouncing around ideas, and we came up with the concept for the chess game and the pigeon. I wanted it to be a pigeon, because I really love pigeons, and birds. We wrote it together, and then we started working on it.

So, I was there from before that existed, and I saw the thing through as well. I also brought in Peter Jackson to do the graphics.

This message unfortunately resonates more than ever. Republicans used to be the war hawks; now, it's Democrats. What a reversal.

It just feels like we live in an upside-down world. Something happened where we went through a wormhole, and we're in this alternate reality. I don't know how it happened. But it's not the only [example]; a lot of things just seem absolutely absurd with the world these days.

But hopefully, it points toward something better. I try to be optimistic. In the Hegelian dialectic, you have to have a thesis and antithesis, and the synthesis is when they fuse to become a better idea. So, I'm hoping that all the tension in society right now is what the final stage of synthesis looks like.

How'd the filmmaking process roll on from there?

Dave had made a really great short film called LOU when he was at Pixar; that was also nominated for an Oscar. He and [producer] Brad [Booker] know a ton of talented people; they have an amazing character designer.

We started sending files back and forth with WingNut in New Zealand; they would be adding the skins to the characters.

One of the first stages was the performance capture, where you basically attach a bunch of ping pong balls to a catsuit and a bicycle helmet. You record the position of these ping pong balls in a three-dimensional space. That gives you the performance that you map the skins onto on the computer later on.

For a couple of years, there was a lot of production. David and his team did a really good job of inventing and designing uniforms for the imaginary armies that never existed, because we really didn't want to identify any army as French or British or German or anything.

We wanted to get a kind of parallel universe — an abstraction of the First World War. We designed it so that one army was based on round geometry, and the other was based on angular geometry.

It was a long process, and it was really fun. I learned a lot about modern computer animation.

Between Em Cooper's GRAMMY-winning "I'm Only Sleeping" video and now this, the Beatles' presence in visual media is expanding outward in a cool way.

I think we've been really fortunate to have a lot of really great projects to give to the world. I've only been working on the Beatles and John Lennon stuff directly in the last couple of years, and it's been really exciting for me.

And a big challenge, obviously, because I don't [hesitates] want to f— up. [Laughs.] But it's been a real honor. And I'm very grateful to my mom for giving me the freedom to try all these wacky ideas. Because a lot of people are like, "Oh, when are you going to stop trying to rehash the past with the Beatles, or John Lennon?"

Because the modern world is as it is, I feel like we have a responsibility to try to make sure that the Beatles and John Lennon's music remains out there in the public consciousness, because I think it's really important. I think the world needs to remember the Beatles' music, and remember John and Yoko. It's really about making sure we don't get lost in the white noise of modernity.

I love Asterisms. Where are you at in your journey as a guitarist? I'm sure you unlocked something here.

Like it's a video game. It's weird — I don't even consider myself a guitar player. I'm just, like, a software. But I think it's more about confidence — because it's really hard for me to get over my insecurity with playing and stuff.

For so many different reasons, it's probably just the way I'm designed — being John and Yoko's kid, growing up with a lot of preconceived notions or expectations about me, musically.

So, it's always been hard to accept myself as a musician, and this was kind of a lesson in getting over myself. Accepting what I wanted to play, and just doing it.

This is my Tzadik record, so it had to be all these fancy, amazing musicians. It doesn't matter what your chops are: it's more about how you feel, and the feeling you bring to your performance.

Once we recorded, it sounded amazing, because we recorded live to tape. So, everything on that album is live, except for my guitar solos. I didn't play my solos live, because I had to play the rhythm guitar. I was just paying attention to the band and cueing people. Once we finished the basic tracks, it just took us a couple of days, and it was done.

It was the simplest record I've ever done, because there were no vocals, so there wasn't a lot of mixing process. We recorded live to 16-track tape, and it was done.

I caught wind a couple of years back that you were working on another solo record simultaneously. Is that true?

I was working on a solo record of songs with lyrics. I finished it, and — I don't know, I think this speaks to the mental problems I have — but I didn't like it suddenly, and i never put it out. I just felt weird about it. I think I overthought it or something.

Then Zorn asked me to do an instrumental thing, and it was a no-brainer, because I've been a fan my whole life. The idea of getting to do something on his label was really an honor.

I got turned on to so many amazing musicians from Zorn, like Joey Baron, Dave Douglas, Kenny Wolleson, and Marc Ribot. Growing up in New York, that's always been my idea of where the greatest musicians are — Zorn and his gang.

Why'd you feel weird about the other album? Did it just not have the juice?

It's not that I didn't think it had the juice. I just got uncomfortable with the idea of putting out a solo record, and the whole process. I got nervous. I still think it's good. But I don't know if it's good enough to warrant me releasing it.

That's fine playing in bands, like the [Claypool Lennon] Delirium and GOASTT [Ghost of a Saber Toothed Tiger]. It takes a degree of unnecessary pressure off of making music. But as soon as your actual birth name is on the record, it starts to feel uncomfortable for me.

People are ruthless today, period. But they're especially critical of me with music. So, it's like, Do I really need to do that s—? It's a little more awkward: "I, myself, Sean Lennon, am putting out my art, and here it is." I'd rather be part of the band.

.jpg)

Photo: Yoko Ono

list

5 Reasons John Lennon's 'Mind Games' Is Worth Another Shot

John Lennon's 1973 solo album 'Mind Games' never quite got its flowers, aside from its hit title track. A spectacular 2024 remix and expansion is bound to amend its so-so reputation.

As the train of Beatles remixes and expansions — solo or otherwise — chugs along, a fair question might come to mind: why John Lennon's Mind Games, and why now?

When you consider some agreed-upon classics — George Harrison's Living in the Material World, Ringo Starr's Ringo — it might seem like it skipped the line. Historically, fans and critics have rarely made much of Mind Games, mostly viewing it as an album-length shell for its totemic title track.

The 2020 best-of Lennon compilation Gimme Some Truth: The Ultimate Mixes featured "Mind Games," "Out the Blue," and "I Know (I Know)," which is about right — even in fanatical Lennon circles, few other Mind Games tracks get much shine. It's hard to imagine anyone reaching for it instead of Plastic Ono Band, or Imagine, or even the controversial, semi-outrageous Some Time in New York City.

Granted, these largely aren't A-tier Lennon songs — but still, the album's tepid reputation has little to do with the material. The original Mind Games mix is, to put it charitably, muddy — partly due to Lennon's insecurity about his voice, partly just due to that era of recordmaking.

The fourth-best Picasso is obviously still worth viewing. But not with an inch of grime on your glasses.

The Standard Deluxe Edition. Photo courtesy of Universal Music Group

That's all changed with Mind Games: The Ultimate Collection — a fairly gobsmacking makeover of the original album, out July 12. Turns out giving it this treatment was an excellent, long-overdue idea — and producer Sean Ono Lennon, remixers Rob Stevens, Sam Gannon and Paul Hicks were the best men for the job. Outtakes and deconstructed "Elemental" and "Elements" mixes round out the boxed set.

It's not that Mind Games: The Ultimate Collection reveals some sort of masterpiece. The album's still uneven; it was bashed out at New York's Record Plant in a week, and it shows. But that's been revealed to not be its downfall, but its intrinsic charm. As you sift through the expanded collection, consider these reasons you should give Mind Games another shot.

The Songs Are Better Than You Remember

Will deep cuts like "Intuition" or "Meat City" necessarily make your summer playlist? Your mileage may vary. However, a solid handful of songs you may have written off due to murky sonics are excellent Lennon.

With a proper mix, "Aisumasen (I'm Sorry)" absolutely soars — it's Lennon's slow-burning, Smokey Robinson-style mea culpa to Yoko Ono. "Bring On the Lucie (Freda Peeple)" has a rickety, communal "Give Peace a Chance" energy — and in some ways, it's a stronger song than that pacifist classic.

And on side 2, the mellow, ruminative "I Know (I Know)" and "You Are Here" sparkle — especially the almost Mazzy Star-like latter tune, with pedal steel guitarist "Sneaky" Pete Kleinow (of Flying Burrito Brothers fame) providing abundant atmosphere.

And, of course, the agreed-upon cuts are even better: "Mind Games" sounds more celestial than ever. And the gorgeous, cathartic "Out the Blue" — led by David Spinozza's classical-style playing, with his old pal Paul McCartney rubbing off on the melody — could and should lead any best-of list.

The Performances Are Killer

Part of the fun of Mind Games: The Ultimate Collection is realizing how great its performances are. They're not simply studio wrapping paper; they capture 1970s New York's finest session cats at full tilt.

Those were: Kleinow, Spinozza, keyboardist Ken Ascher, bassist Gordon Edwards, drummer Jim Keltner (sometimes along with Rick Marotta), saxophonist Michael Brecker, and backing vocalists Something Different.

All are blue-chip; the hand-in-glove rhythm section of Edwards and Keltner is especially captivating. (Just listen to Edwards' spectacular use of silence, as he funkily weaves through that title track.)

The hardcover book included in Mind Games: The Ultimate Collection is replete with the musicians' fly-on-the-wall stories from that week at the Record Plant.

"You can hear how much we're all enjoying playing together in those mixes," Keltner says in the book, praising Spinozza and Gordon. "If you're hearing John Lennon's voice in your headphones and the great Kenny Ascher playing John's chords on the keys, there's just no question of where you're going and how you're going to get there."

It Captures A Fascinating Moment In Time

"Mind Games to me was like an interim record between being a manic political lunatic to back to being a musician again," Lennon stated, according to the book. "It's a political album or an introspective album. Someone told me it was like Imagine with balls, which I liked a lot."

This creative transition reflects the upheaval in Lennon's life at the time. He no longer had Phil Spector to produce; Mind Games was his first self-production. He was struggling to stay in the country, while Nixon wanted him and his message firmly out.

Plus, Lennon recorded it a few months before his 18-month separation from Ono began — the mythologized "Lost Weekend" that was actually a creatively flourishing time. All of this gives the exhaustive Mind Games: The Ultimate Collection historical weight, on top of listening pleasure.

"[It's important to] get as complete a revealing of it as possible," Stevens, who handled the Raw Studio Mixes, tells GRAMMY.com. "Because nobody's going to be able to do it in 30 years."

John Lennon and Yoko Ono in Central Park, 1973. Photo: Bob Gruen

Moments Of Inspired Weirdness Abound

Four seconds of silence titled the "Nutopian International Anthem." A messy slab of blues rock with refrains of "Fingerlickin', chicken-pickin'" and "Chickin-suckin', mother-truckin'." The country-fried "Tight A$," basically one long double entendre.

To put it simply, you can't find such heavy concentrates of Lennonesque nuttiness on more commercial works like Imagine. Sometimes the outliers get under your skin just the same.

It's Never Sounded Better

"It's a little harsh, a little compressed," Stevens says of the original 1973 mix. "The sound's a little bit off-putting, so maybe you dismiss listening to it, in a different head. Which is why the record might not have gotten its due back then."

As such, in 2024 it's revelatory to hear Edwards' basslines so plump, Keltner's kick so defined, Ascher's lines so crystalline. When Spinozza rips into that "Aisumasen" solo, it absolutely penetrates. And, as always with these Lennon remixes, the man's voice is prioritized, and placed front and center. It doesn't dispose of the effects Lennon insecurely desired; it clarifies them.

"I get so enthusiastic," Ascher says about listening to Mind Games: The Ultimate Collection. "I say, 'Well, that could have been a hit. This could have been a hit. No, this one could have been a hit, this one." Yes is the answer.

Photo: Archive Photos/Getty Images

list

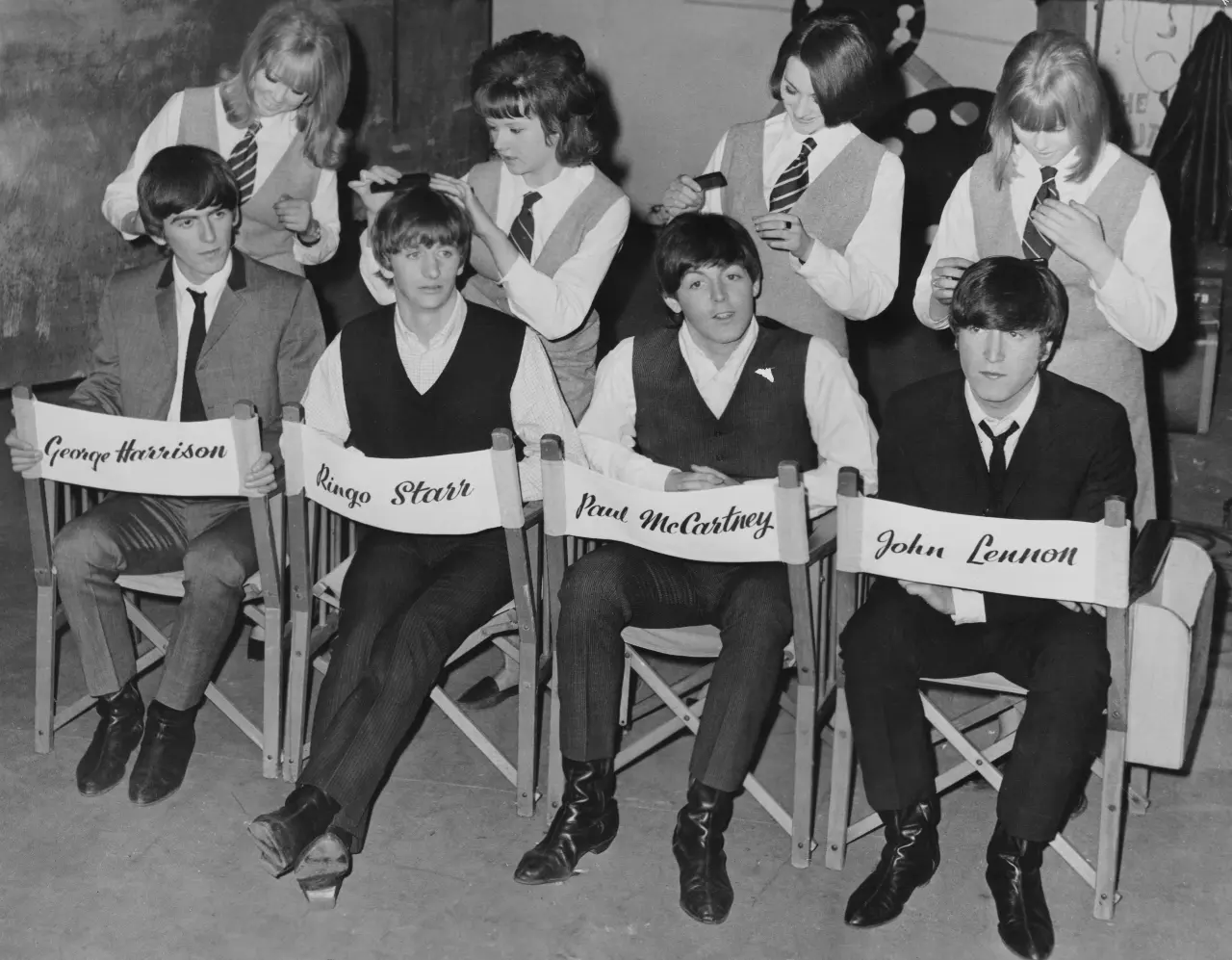

'A Hard Day's Night' Turns 60: 6 Things You Can Thank The Beatles Film & Soundtrack For

This week in 1964, the Beatles changed the world with their iconic debut film, and its fresh, exuberant soundtrack. If you like music videos, folk-rock and the song "Layla," thank 'A Hard Day's Night.'

Throughout his ongoing Got Back tour, Paul McCartney has reliably opened with "Can't Buy Me Love."

It's not the Beatles' deepest song, nor their most beloved hit — though a hit it was. But its zippy, rollicking exuberance still shines brightly; like the rest of the oldies on his setlist, the 82-year-old launches into it in its original key. For two minutes and change, we're plunged back into 1964 — and all the humor, melody, friendship and fun the Beatles bestowed with A Hard Day's Night.

This week in 1964 — at the zenith of Beatlemania, after their seismic appearance on "The Ed Sullivan Show" — the planet received Richard Lester's silly, surreal and innovative film of that name. Days after, its classic soundtrack dropped — a volley of uber-catchy bangers and philosophical ballads, and the only Beatles LP to solely feature Lennon-McCartney songs.

As with almost everything Beatles, the impact of the film and album have been etched in stone. But considering the breadth of pop culture history in its wake, Fab disciples can always use a reminder. Here are six things that wouldn't be the same without A Hard Day's Night.

All Music Videos, Forever

Right from that starting gun of an opening chord, A Hard Day's Night's camerawork alone — black and white, inspired by French New Wave and British kitchen sink dramas — pioneers everything from British spy thrillers to "The Monkees."

Across the film's 87 minutes, you're viscerally dragged into the action; you tumble through the cityscapes right along with John, Paul, George, and Ringo. Not to mention the entire music video revolution; techniques we think of as stock were brand-new here.

According to Roger Ebert: "Today when we watch TV and see quick cutting, hand-held cameras, interviews conducted on the run with moving targets, quickly intercut snatches of dialogue, music under documentary action and all the other trademarks of the modern style, we are looking at the children of A Hard Day's Night."

Emergent Folk-Rock

George Harrison's 12-string Rickenbacker didn't just lend itself to a jangly undercurrent on the A Hard Day's Night songs; the shots of Harrison playing it galvanized Roger McGuinn to pick up the futuristic instrument — and via the Byrds, give the folk canon a welcome jolt of electricity.

Entire reams of alternative rock, post-punk, power pop, indie rock, and more would follow — and if any of those mean anything to you, partly thank Lester for casting a spotlight on that Rick.

The Ultimate Love Triangle Jam

From the Byrds' "Triad" to Leonard Cohen's "Famous Blue Raincoat," music history is replete with odes to love triangles.

But none are as desperate, as mannish, as garment-rending, as Derek and the Dominoes' "Layla," where Eric Clapton lays bare his affections for his friend Harrison's wife, Pattie Boyd. Where did Harrison meet her? Why, on the set of A Hard Day's Night, where she was cast as a schoolgirl.

Debates, Debates, Debates

Say, what is that famous, clamorous opening chord of A Hard Day's Night's title track? Turns out YouTube's still trying to suss that one out.

"It is F with a G on top, but you'll have to ask Paul about the bass note to get the proper story," Harrison told an online chat in 2001 — the last year of his life.

A Certain Strain Of Loopy Humor

No wonder Harrison got in with Monty Python later in life: the effortlessly witty lads were born to play these roles — mostly a tumble of non sequiturs, one-liners and daffy retorts. (They were all brought up on the Goons, after all.) When A Hard Day's Night codified their Liverpudlian slant on everything, everyone from the Pythons to Tim and Eric received their blueprint.

The Legitimacy Of The Rock Flick

What did rock 'n' roll contribute to the film canon before the Beatles? A stream of lightweight Elvis flicks? Granted, the Beatles would churn out a few headscratchers in its wake — Magical Mystery Tour, anyone? — but A Hard Day's Night remains a game-changer for guitar boys on screen.

The best part? The Beatles would go on to change the game again, and again, and again, in so many ways. Don't say they didn't warn you — as you revisit the iconic A Hard Day's Night.

Explore The World Of The Beatles

.webp)

5 Reasons John Lennon's 'Mind Games' Is Worth Another Shot

'A Hard Day's Night' Turns 60: 6 Things You Can Thank The Beatles Film & Soundtrack For

6 Things We Learned From Disney+'s 'The Beach Boys' Documentary

5 Lesser Known Facts About The Beatles' 'Let It Be' Era: Watch The Restored 1970 Film

Catching Up With Sean Ono Lennon: His New Album 'Asterisms,' 'War Is Over!' Short & Shouting Out Yoko At The Oscars

Photo: Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

list

6 Things We Learned From Disney+'s 'The Beach Boys' Documentary

From Brian Wilson's obsession with "Be My Baby" and the Wall Of Sound, to the group's complicated relationship with Murry Wilson and Dennis Wilson's life in the counterculture, 'The Beach Boys' is rife with insights from the group's first 15 years.

It may seem like there's little sand left to sift through, but a new Disney+ documentary proves that there is an endless summer's worth of Beach Boys stories to uncover.

While the legendary group is so woven into the fabric of American culture that it’s easy to forget just how innovative they were, a recently-released documentary aims to remind. The Beach Boys uses a deft combination of archival footage and contemporary interviews to introduce a new generation of fans to the band.

The documentary focuses narrowly on the first 15 years of the Beach Boys’ career, and emphasizes what a family affair it was. Opening the film is a flurry of comments about "a certain family blend" of voices, comparing the band to "a fellowship," and crediting the band’s success directly to having been a family. The frame is apt, considering that the first lineup consisted of Wilson brothers Brian, Dennis, and Carl, their cousin Mike Love, and high school friend Al Jardine, and their first manager was the Wilsons’ father, Murry.

All surviving band members are interviewed, though a very frail Brian Wilson — who was placed under a conservatorship following the January death of his wife Melinda — appears primarily in archival footage. Additional perspective comes via musicians and producers including Ryan Tedder, Janelle Monáe, Lindsey Buckingham, and Don Was, and USC Vice Provost for the Arts Josh Kun.

Thanks to the film’s tight focus and breadth of interviewees, it includes memorable takeaways for both longtime fans and ones this documentary will create. Read on for five takeaways from Disney+'s The Beach Boys.

Family Is A Double-Edged Sword

For all the warm, tight-knit imagery of the Beach Boys as a family band, there was an awful lot of darkness at the heart of their sunny sound, and most of the responsibility for that lies with Wilson family patriarch Murry Wilson. Having written a few modest hits in the late 1930s, Murry had talent and a good ear, and he considered himself a largely thwarted genius.

When Brian, Dennis, and Carl formed the Beach Boys with their cousin Mike Love and friend Al Jardine, Murry came aboard as the band’s manager. In many respects, he was capable; his dogged work ethic and fierce protectiveness helped shepherd the group to increasingly high profile successes. He masterminded the extended Wilson family call-in campaign to a local radio station, pushing the Beach Boys’ first single "Surfin’" to become the most popular song in Los Angeles. He relentlessly shopped their demos to music labels, eventually landing them a contract at Capitol Records. He supported the band’s strong preference to record at Western Recordings rather than Capitol Records’ own in-house studio, and was an excellent promoter.

Murry Wilson was also extremely controlling, fining the band when they made mistakes or swore, and "was miserable most of the time," according to his wife Audree.

Footage from earlier interviews with Carl and Dennis, and contemporary comments from Mike Love make it clear that Murry was emotionally and physically abusive to his sons throughout their childhoods. He even sold off the Beach Boys’ songwriting catalog without consulting co-owner Brian, a moment that Brian’s ex-wife Marilyn says he felt so keenly that he took to his bed and didn’t get up for three days.

Murry Wilson was at best a very complicated figure, both professionally jealous of his own children to a toxic degree and devoted to ensuring their success.

"Be My Baby" and The Wrecking Crew Changed Brian Wilson’s Life

"Be My Baby," which Phil Spector had produced for the Ronettes in 1963, launched the girl group to immediate iconic status. The song also proved life-changing for Brian. On first hearing the song, "it spoke to my soul," and Brian threw himself into learning how Spector created his massive, lush Wall of Sound. Spector’s approach taught Brian that production was a meaningful art that creates an "overall sound, what [the listeners] are going to hear and experience in two and a half minutes."

By working with The Wrecking Crew — a truly motley bunch of experienced, freewheeling musicians who played on Spector’s records and were over a decade older than the Beach Boys — Brian’s artistic sensibility quickly emerged. According to drummer Hal Blaine and bassist Carol Kaye, Brian not knowing what he didn’t know gave him the freedom and imagination to create sounds that were completely new and innovative.

Friendly Rivalries With Phil Spector & The Beatles Yielded Amazing Pop Music

According to popular myth, the Beach Boys and the Beatles saw each other exclusively as almost bitter rivals for the ears, hearts, and disposable income of their fans. The truth is more nuanced: after the initial shock of the British Invasion wore off, the two groups developed and maintained a very productive, admiration-based competition, each band pushing the other to sonic greatness.

Cultural historian and academic Josh Kun reframes the relationship between the two bands as a "transatlantic collaboration," and asks, "If they hadn’t had each other, would they have become what they became?" Could they have made the historic musical leaps that we now take for granted?

Read more: 10 Memorable Oddities By The Beach Boys: Songs About Root Beer, Raising Babies & Ecological Collapse

The release of Rubber Soul left Brian Wilson thunderstruck. The unexpected sitar on "Norwegian Wood," the increasingly mature, personal songwriting, all of it was so fresh that "I flipped!" and immediately wanted to record "a thematic album, a collection of folk songs."

Brian found life on the road soul-crushing and terrifying, and was much more content to stay home composing, writing, and producing. With the touring band out on the road, and with a creative fire lit under him by both the Beatles and Phil Spector’s Wall of Sound, he had time to develop into a wildly creative, exacting, and celebrated producer, an experience that yielded the 1966 masterpiece, Pet Sounds.

Pet Sounds Took 44 Years To Go Platinum

You read that right: Pet Sounds was a flop in the U.S. upon its release. Even after hearing radio-ready tracks like "Wouldn’t It Be Nice?" and "Sloop John B" and the ravishing "God Only Knows," Capitol Records thought the album had minimal commercial potential and didn’t give it the promotional push the band were expecting. Fans in the United Kingdom embraced it, however, and the votes of confidence from British fans — including Keith Moon, John Lennon, and Paul McCartney — buoyed both sales and the Beach Boys’ spirits.

In fact, Lennon and McCartney credited Pet Sounds with giving them a target to hit when they went into the studio to record the Beatles’ own next sonically groundbreaking album, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. As veteran producer and documentary talking head Don Was puts it, Brian Wilson was a true pioneer, incorporating "textures nobody had ever put into pop music before." The friendly rivalry continued as the Beatles realized that they needed to step up their game once more.

Read more: Masterful Remixer Giles Martin On The Beach Boys' 'Pet Sounds,' The Beatles, Paul McCartney

Meanwhile, Capitol Records released and vigorously promoted a best-of album full of the Beach Boys’ early hits, Best Of The Beach Boys. The collection of sun-drenched, peppy tunes was a hit, but was also very out of step with the cultural and political shifts bubbling up through the anti-war and civil rights movements of the era. Thanks in part to later critical re-appraisals and being publicly embraced by musicians as varied as Questlove and Stereolab, Pet Sounds eventually reached platinum status in April 2000, 44 years after its initial release.

Dennis Wilson Was The Only Truly Beachy Beach Boy

Although the Beach Boys first made a name for themselves as purveyors of "the California sound" by singing almost exclusively about beaches, girls, and surfing, the only member of the band who really liked the beach was drummer Dennis Wilson.

Al Jardine ruefully recalls that "the first thing I did was lose my board — I nearly drowned" on a gorgeous day at Manhattan beach. Dennis was an actual surfer whose tanned, blonde good looks and slightly rebellious edge made him the instant sex symbol of the group. In 1967, when Brian’s depression was the deepest and he relinquished in-studio control of the band, Dennis flourished musically and lyrically. Carl Wilson, who had emerged as a very capable producer in Brian’s absence, described Dennis as evolving artistically "really quite amazingly…it just blew us away."

Dennis was also the only Beach Boy who participated meaningfully in the counterculture of the late 1960s, a movement the band largely sat out of, largely to the detriment of their image. He introduced the band to Transcendental Meditation — a practice Mike Love maintains to this day — and was a figure in the Sunset Strip and Laurel Canyon music scenes. Unfortunately, he also became acquainted with and introduced his bandmates to Charles Manson. Manson’s true goal was rock stardom; masterminding the gruesome mass murders that his followers perpetrated in 1969 was a vengeful outgrowth of his thwarted ambition.

The Beach Boys did record and release a reworked version of one of Manson’s songs, "Never Learn Not To Love" as a B-side in 1968. Love says that having introduced Manson to producer Terry Melcher, who firmly rebuffed the would-be musician, "weighed on Dennis pretty heavily," and while Jardine emphatically and truthfully says "it wasn’t his fault," it’s easy to imagine those events driving some of the self-destructive alcohol and drug abuse that marked Dennis’ later years.

The Journey From Obscurity To Perennially Popular Heritage Act

The final minutes of The Beach Boys can be summed up as "if all else fails commercially, release a double album of beloved greatest hits." The 1970s were a very fruitful time for the band creatively, as they invited funk specialists Blondie Chaplin and Ricky Fataar to join the band and relocated to the Netherlands to pursue a harder, more far-out sound. Although the band were proud of the lush, singer/songwriter material they were recording, the albums of this era were sales disappointments and represented a continuing slide into uncoolness and obscurity.

Read more: Brian Wilson Is A Once-In-A-Lifetime Creative Genius. But The Beach Boys Are More Than Just Him.

Once again, Capitol Records turned to the band’s early material to boost sales. The 1974 double-album compilation Endless Summer, comprised of hits from 1962-1965, went triple platinum, relaunching The Beach Boys as a successful heritage touring act. A new generation of fans — "8 to 80," as the band put it — flocked to their bright harmonies and upbeat tempos, as seen in the final moments of the documentary when the Beach Boys played to a crowd of over 500,000 fans on July 4, 1980.

While taking their place as America’s Band didn’t do much to make them cool, it did ensure one more wave of chart success with 1988’s No. 1 hit "Kokomo" and ultimately led to broader appreciation for Pet Sounds and its sibling experimental albums like Smiley Smile. That wave of popularity has proven remarkably durable; after all, they’ve ridden it to a documentary for Disney+ nearly 45 years later.

Listen: 50 Essential Songs By The Beach Boys Ahead Of "A GRAMMY Salute" To America's Band

Photo: Ethan A. Russell / © Apple Corps Ltd

list

5 Lesser Known Facts About The Beatles' 'Let It Be' Era: Watch The Restored 1970 Film

More than five decades after its 1970 release, Michael Lindsay-Hogg's 'Let it Be' film is restored and re-released on Disney+. With a little help from the director himself, here are some less-trodden tidbits from this much-debated film and its album era.

What is about the Beatles' Let it Be sessions that continues to bedevil diehards?

Even after their aperture was tremendously widened with Get Back — Peter Jackson's three-part, almost eight hour, 2021 doc — something's always been missing. Because it was meant as a corrective to a film that, well, most of us haven't seen in a long time — if at all.

That's Let it Be, the original 1970 documentary on those contested, pivotal, hot-and-cold sessions, directed by Michael Lindsay-Hogg. Much of the calcified lore around the Beatles' last stand comes not from the film itself, but what we think is in the film.

Let it Be does contain a couple of emotionally charged moments between maturing Beatles. The most famous one: George Harrison getting snippy with Paul McCartney over a guitar part, which might just be the most blown-out-of-proportion squabble in rock history.

But superfans smelled blood in the water: the film had to be a locus for the Beatles' untimely demise. To which the film's director, Michael Lindsay-Hogg, might say: did we see the same movie?

"Looking back from history's vantage point, it seems like everybody drank the bad batch of Kool-Aid," he tells GRAMMY.com. Lindsay-Hogg had just appeared at an NYC screening, and seemed as surprised by it as the fans: "Because the opinion that was first formed about the movie, you could not form on the actual movie we saw the other night."

He's correct. If you saw Get Back, Lindsay-Hogg is the babyfaced, cigar-puffing auteur seen throughout; today, at 84, his original vision has been reclaimed. On May 8, Disney+ unveiled a restored and refreshed version of the Let it Be film — a historical counterweight to Get Back. Temperamentally, though, it's right on the same wavelength, which is bound to surprise some Fabs disciples.

With the benefit of Peter Jackson's sound-polishing magic and Giles Martin's inspired remixes of performances, Let it Be offers a quieter, more muted, more atmospheric take on these sessions. (Think fewer goofy antics, and more tight, lingering shots of four of rock's most evocative faces.)

As you absorb the long-on-ice Let it Be, here are some lesser-known facts about this film, and the era of the Beatles it captures — with a little help from Lindsay-Hogg himself.

The Beatles Were Happy With The Let It Be Film

After Lindsay-Hogg showed the Beatles the final rough cut, he says they all went out to a jovial meal and drinks: "Nice food, collegial, pleasant, witty conversation, nice wine."

Afterward, they went downstairs to a discotheque for nightcaps. "Paul said he thought Let it Be was good. We'd all done a good job," Lindsay-Hogg remembers. "And Ringo and [wife] Maureen were jiving to the music until two in the morning."

"They had a really, really good time," he adds. "And you can see like [in the film], on their faces, their interactions — it was like it always was."

About "That" Fight: Neither Paul Nor George Made A Big Deal

At this point, Beatles fanatics can recite this Harrison-in-a-snit quote to McCartney: "I'll play, you know, whatever you want me to play, or I won't play at all if you don't want me to play. Whatever it is that will please you… I'll do it." (Yes, that's widely viewed among fans as a tremendous deal.)

If this was such a fissure, why did McCartney and Harrison allow it in the film? After all, they had say in the final cut, like the other Beatles.

"Nothing was going to be in the picture that they didn't want," Lindsay-Hogg asserts. "They never commented on that. They took that exchange as like many other exchanges they'd had over the years… but, of course, since they'd broken up a month before [the film's release], everyone was looking for little bits of sharp metal on the sand to think why they'd broken up."

About Ringo's "Not A Lot Of Joy" Comment…

Recently, Ringo Starr opined that there was "not a lot of joy" in the Let it Be film; Lindsay-Hogg says Starr framed it to him as "no joy."

Of course, that's Starr's prerogative. But it's not quite borne out by what we see — especially that merry scene where he and Harrison work out an early draft of Abbey Road's "Octopus's Garden."

"And Ringo's a combination of so pleased to be working on the song, pleased to be working with his friend, glad for the input," Lindsay-Hogg says. "He's a wonderful guy. I mean, he can think what he wants and I will always have greater affection for him.

"Let's see if he changes his mind by the time he's 100," he added mirthfully.

Lindsay-Hogg Thought It'd Never Be Released Again

"I went through many years of thinking, It's not going to come out," Lindsay-Hogg says. In this regard, he characterizes 25 or 30 years of his life as "solitary confinement," although he was "pushing for it, and educating for it."

"Then, suddenly, the sun comes out" — which may be thanks to Peter Jackson, and renewed interest via Get Back. "And someone opens the cell door, and Let it Be walks out."

Nobody Asked Him What The Sessions Were Like

All four Beatles, and many of their associates, have spoken their piece on Let it Be sessions — and journalists, authors, documentarians, and fans all have their own slant on them.

But what was this time like from Lindsay-Hogg's perspective? Incredibly, nobody ever thought to check. "You asked the one question which no one has asked," he says. "No one."

So, give us the vibe check. Were the Let it Be sessions ever remotely as tense as they've been described, since man landed on the moon? And to that, Lindsay-Hogg's response is a chuckle, and a resounding, "No, no, no."