Photo: Vivian Wang

Norah Jones

news

Norah Jones On Her Two-Decade Evolution, Channeling Chris Cornell & Her First-Ever Live Album, ''Til We Meet Again'

On ''Til We Meet Again,' Norah Jones and her band confidently twist selections from her 20-year songbook—and an unexpected Soundgarden cover—into fascinating new shapes

Just over a week after Chris Cornell wailed Led Zeppelin's "In My Time of Dying" at Detroit's Fox Theater mere hours before taking his life, Norah Jones stepped onto that same stage. Near the end of the set, her band took five, and she sang Soundgarden's "Black Hole Sun" onstage for the first time—and maybe the last.

Jones had spent the day woodshedding the song in her dressing room. "I was kind of nervous," the eight-time GRAMMY winner and 17-time nominee admits to GRAMMY.com. "But I thought, 'We're going to send some love to him and do this song of his.'" Despite "Black Hole Sun" not immediately being in Jones' wheelhouse, the performance was a spectral success. "It was probably one of the most beautiful live moments I've ever had," she says. "I don't know if his ghost was in the room or what, but it carried me through that song like I could have never imagined."

"It's just one of those moments I'm really glad we could capture," Jones adds, "because I don't even know if I'll play that song again."

"Black Hole Sun'' concludes her first-ever live album, 'Til We Meet Again, which drops April 16 on Blue Note. If Jones hadn't recorded all of her gigs for the past eight years, each of its 14 tracks could have evaporated with the final piano chord. Sumptuous versions of her staples like "I've Got to See You Again" (in France, in 2018) and "Sunrise" (in Argentina, in 2019) demonstrate how Jones has developed her improvisatory muscles over her two-decade career.

Jones curated 'Til We Meet Again as a response to COVID and a nearly concert-free year. Now that vaccines are rolling out (her second shot is around the corner), she's ready to jump back on stage when the time is right. Until then, for those unaware of Jones' live prowess, this impeccably recorded live album is more than enough to chew on.

GRAMMY.com caught up with Norah Jones over Zoom to discuss the origin of 'Til We Meet Again, the thrill of collaborating with the greatest jazz musicians alive and her hot-and-cold relationship with the word "jazz."

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//-6JfRFPp7sI' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

This interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

I'm curious about the timing of 'Til We Meet Again. Had the idea for a live record been percolating for a while, or was it a response to a year without gigs?

More the latter. I'd done a couple of live DVD types of things where you plan to do it and you record it with a camera crew, but this came about [because] I was listening to one of the last shows we did. We've recorded every show for the last eight years because… technology, you know [chuckles]. It's easy to do!

And so I was listening to one of the last shows we did and it just felt so good, especially in the absence of having access to live music and playing shows. So I wanted to put it out. I just decided then, last summer. And then we decided to sort of comb through some of the more similar band-lineup shows to that show to make sure we get the best version of everything, basically.

Where was that show you mentioned?

That show was in Rio. It was in December 2019. We did a South American tour with a trio, which has been a fun setup for me recently. More piano-based.

Who was the rhythm section? Was Brian [Blade] on drums?

Yeah, Brian on drums. In December, it was Jesse Murphy on bass, but the first tour I did with that setup was with Chris Thomas on bass and Brian on drums. And actually, Pete Remm was on organ. This was, like, 2018, maybe. So we went back to those first shows I did with that setup and took some of that stuff because it was a really special opening-up of the songs with that setup.

I love trio albums, by the way. I've interviewed people like Bill Frisell and Vijay Iyer and they talked a lot about them. Do you have any favorites?

I mean, I've always loved the Bill Evans Trio [Sunday at the Village Vanguard]. That's pretty great. Classic. And I love some of the classic piano-player/singing trios. Like, Shirley Horn had a great thing. I love hearing Nina Simone when it's just bass, drums and her. Even if there's a bigger band, I love when it's stripped back.

All you need is Nina.

Really, all you need is Nina! But when the drum kicks in with that light, little groove, it's pretty great.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//SMtqLM5pwss' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

While listening to 'Til We Meet Again, I was more absorbed in the songs than noticing how many instruments there were. Is it mostly trios or are there quartets and such?

Well, it's mostly a trio, but I did have an organ on quite a bit of it. For me, that's a lot different than having a guitar. I don't know why. The thing missing from this album that has been present, I feel like, for my whole career, is the guitar. Guitar has been a big part of most of the songs I do. Not all of them. But at least touring, this is the first time I've toured without a guitar. Over the last few years, I've dabbled without a guitar. I mean, I play a little guitar.

This album had a few different instruments on it, though, because the songs were in Rio where we had a percussionist sit in and also a flute player. Jorge [Continentino] sat in. Then, on one song, Jesse Harris sat in on guitar in Rio, as well.

Not that he's on this record, but on the topic of the organ, I was just thinking about how you've played with Dr. Lonnie Smith.

Oh, yeah. He played on Day Breaks. That was amazing.

When you survey the last two decades, how would you say you've developed as a live performer?

I mean, it's all just an evolution. And I'll continue to change, right? I think what's cool about this album is that I'm close to it. I've been changing and adapting for the last 20 years, but to someone who might not have seen me live recently or at all, maybe it represents a whole different side of these songs.

The way you guys are taking control of the rhythms, shifting and shaping them, is really nice.

Yeah. Brian's so fun to play with. It's a joy, you know? And also, the nice thing about playing with a trio is that you can go to different places without planning it out. It's a little easier without multiple chordal instruments.

Obviously, Brian is so versed in that format. That excellent album with Chick Corea and Christian McBride, [2021's GRAMMY-winning] Trilogy 2, comes to mind.

Brian is amazing. He will go wherever the moment takes him in the music. He's not tied to anything. But he'll also lay down the sickest groove [laughs], you know what I mean? So, he's the best of everything.

I get the sense that you're just as much a fan of your accompanists as the people in the audience.

Oh, definitely. I saw Brian play when I was in high school. I went to see him play with Joshua Redman. It might have been Chris Thomas on bass? I remember because I was telling them about it and they were mad at me for saying [naive voice] "Oh, I was in high school!" They're only a few years older than me. But I've been a fan of Brian's for a long time, now, absolutely.

I was just thinking about how you're from the singer/songwriter realm and Joni Mitchell is, too, obviously. But she played with the greatest jazz musicians in her day and now you're doing the same. That must feel pretty cool.

Yeah, some of my favorite recordings of Wayne Shorter are on Joni's albums! But, I mean, I come from a jazz background. I came from that into the singer-songwriter world, kind of. So I feel like going back to playing with people who come from that world also feels very natural.

Norah Jones performing on "Saturday Night Live" in 2002. Photo: Dana Edelson/NBCU Photo Bank/NBCUniversal via Getty Images

You totally don't have to address this if you don't want to, but back in 2002, it must have been annoying to have to prove your jazz roots to people.

Not really. I mean, I felt very conflicted about the jazz roots 20 years ago because I felt like my album was a departure. I feel like people called me a jazz singer when that wasn't representative of the actual album. I didn't want people to not realize what "jazz" was. It was kind of loaded.

I used to be part of the jazz police [laughs]. Like, I used to be that kid. Then, my album was so successful and it really wasn't jazz. It was a foray into different things for me. I didn't want other people to think it was for jazz, for jazz's sake. I was like, "No! Billie Holiday! Not me!" Does that make sense?

Of course. There's folk, soul, country…

The genre titles are tricky for me. But I don't really care anymore. And I didn't then, that much. I just felt like it was confusing.

I haven't met a single musician in the jazz world that's fully comfortable with the word. They're always trying to push back on it, and rightfully so. They've been doing that since the '40s or earlier.

I guess! Have they? Was it weird for people back then? It seems like back then, it was just what it was.

I've read that Miles Davis considered it tantamount to a racial slur.

Really! I feel like these days, I'm more connected to those roots of mine than I was. I feel like for a while, I kind of strayed from that world and was excited to be all things. And now, I'm really excited to have that basis in what I do. I just don't like genres. I find them kind of silly. Sorry, GRAMMYs! [laughs]

No apologies! To me, genres are only useful if you're in a record store and you don't know what to buy.

Exactly.

Before I jump back into the record, are you a Yusef Lateef fan?

[excitedly] You know what? I just started listening to him this week! It's amazing! It kind of sounds like that Éthiopiques stuff a little bit. Where's he from?

He was from Detroit.

What did he say about [the word "jazz"]?

I've been told he gave a dissertation where he brought up representatives from the dictionary and challenged them on the word "jazz," because it had connotations of being dirty or low-grade, with meanings ranging from "nonsense" to "fornication."

I get that. The connotations are that it's not as serious an art form, basically. It's such a silly thing, right? It's not silly at all—I get it—but even my own feelings about it are so silly sometimes.

Well, what are your feelings about it?

It's just music, you know? To get hung up on a word, I think, is not about the music. I respect what he's saying. I'm not talking bad about him. I'm just saying that in general, the whole conversation about it is so funny.

I like that Bird called it "modern music" instead.

I love that. I'm in for that.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//Eywb15ptYUY' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

So, I was going to ask about which of these gigs were particularly memorable for you, but you sort of answered that question when you said it grew out of the Rio show. What about the others, though? Any interesting stories attached to them?

Actually, the France gig was one of the first gigs we did with this band that felt so good. The audience was great. I remember after that show, thinking, "Ah, man! That was awesome!" So when we were going back to think about shows, I said, "Remember that gig in Perpignan that was so good? Do you have that recorded?" And he did. So that was part of it.

And then the Ohana Festival was so special because it was just a big, huge, outdoor festival, which we hadn't really done out with this band. I didn't know how it would go over, but it was awesome. We actually did the song "It Was You," which is from an EP I put out a couple of years ago [2019's Begin Again], and I don't even think it had come out yet. Even if it had, it wasn't something a lot of people had. I don't think it was a hit! [laughs].

So, we played this song from it and the audience didn't know it at all, but the reaction was everything I've ever wanted for that song. It was so great. I'm just so glad we captured that too, you know?

It's the energy feedback! That's what we're missing when we're singing for each other through tinny phone speakers.

Yeah, exactly. During this pandemic, I've made playlists to just feel good, and one of them had a Bob Marley Live track on it. Every time the song comes on and I feel the energy of that, it just makes me kind of electric, you know? It makes me so happy. That's what I was trying to capture. That's what the Rio show had, 100%.

The Brazilian audience is so vocal as well, which helps, but it just had that energy. We were trying to keep that throughout the album. So, there were some songs that there were two great versions of, but one where you could just feel the live energy more. We would choose the energy one. We tried to keep that going.

Norah Jones performing in Florence, Massachusetts, in 2019. Photo: David Barnum

I love the cover of "Black Hole Sun" here. It's unexpected coming from you, but it fits like a glove. Can you talk about your relationship with Chris Cornell's music?

Yeah, I grew up listening to Soundgarden and loved it. I was a kid of the '90s, you know? It was on the air at all times. I got to meet him once. He was super sweet. We shared a dressing room bathroom at a festival [chuckles]. At the Bridge School [Benefit], actually. He was such a great singer, so I was a fan.

And when he died, we happened to be playing the same theater the night he died, in Detroit. I think we were the first people to play it since he played there that week. My guitar player told me that morning that this is where he had played. So, I thought it would be nice to play "Black Hole Sun" as a tribute.

I practiced it all day in my dressing room. I was kind of nervous, but I thought, "We're going to send some love to him and do this song of his." It was probably one of the most beautiful live moments I've ever had. The song is beautiful and, somehow, the music, his spirit—I don't know if his ghost was in the room or what, but it carried me through that song like I could have never imagined.

It's just one of those moments I'm really glad we could capture because I don't even know if I'll play that song again. It was such a special time to play it and I don't know if I could ever recapture that. Just the vibe in the room, you know.

I feel like a different musician might do a more melodramatic version of "Black Hole Sun." I appreciate that you just inhabited the melody and let it speak for itself because I think he was a Beatles- or Kurt Cobain-level melody writer.

Oh, totally. I'd known that song forever, but I'd never tried to play it. And when I was learning it that day, I was like, "Holy crap! This song is crazy! It's so good; it's so unique; it's so interesting." And the lyrics are so beautiful as well.

What's your plan for 2021 and beyond now that we're all hopefully getting our vaccines? I'm sure you're raring to return to the stage.

Yeah, I'm so excited! I get my second shot in a few weeks. I'm really excited to return to the stage, but I don't know when. I'm just going to wait until things completely return. I'm going to let everyone who is really raring to go, go. I can't imagine doing it before 2022, but I'm down if it happens! [laughs] I'm ready!

The problem might be that everyone will want to go back out at once.

Yeah. And also, I'm cool for a minute. I don't know. I don't want to cobble it together. The half-capacity thing… I'll go to those shows, but I don't know. I don't want to jump the gun myself, but I'm excited.

.jpg)

Photo: Yoko Ono

list

5 Reasons John Lennon's 'Mind Games' Is Worth Another Shot

John Lennon's 1973 solo album 'Mind Games' never quite got its flowers, aside from its hit title track. A spectacular 2024 remix and expansion is bound to amend its so-so reputation.

As the train of Beatles remixes and expansions — solo or otherwise — chugs along, a fair question might come to mind: why John Lennon's Mind Games, and why now?

When you consider some agreed-upon classics — George Harrison's Living in the Material World, Ringo Starr's Ringo — it might seem like it skipped the line. Historically, fans and critics have rarely made much of Mind Games, mostly viewing it as an album-length shell for its totemic title track.

The 2020 best-of Lennon compilation Gimme Some Truth: The Ultimate Mixes featured "Mind Games," "Out the Blue," and "I Know (I Know)," which is about right — even in fanatical Lennon circles, few other Mind Games tracks get much shine. It's hard to imagine anyone reaching for it instead of Plastic Ono Band, or Imagine, or even the controversial, semi-outrageous Some Time in New York City.

Granted, these largely aren't A-tier Lennon songs — but still, the album's tepid reputation has little to do with the material. The original Mind Games mix is, to put it charitably, muddy — partly due to Lennon's insecurity about his voice, partly just due to that era of recordmaking.

The fourth-best Picasso is obviously still worth viewing. But not with an inch of grime on your glasses.

The Standard Deluxe Edition. Photo courtesy of Universal Music Group

That's all changed with Mind Games: The Ultimate Collection — a fairly gobsmacking makeover of the original album, out July 12. Turns out giving it this treatment was an excellent, long-overdue idea — and producer Sean Ono Lennon, remixers Rob Stevens, Sam Gannon and Paul Hicks were the best men for the job. Outtakes and deconstructed "Elemental" and "Elements" mixes round out the boxed set.

It's not that Mind Games: The Ultimate Collection reveals some sort of masterpiece. The album's still uneven; it was bashed out at New York's Record Plant in a week, and it shows. But that's been revealed to not be its downfall, but its intrinsic charm. As you sift through the expanded collection, consider these reasons you should give Mind Games another shot.

The Songs Are Better Than You Remember

Will deep cuts like "Intuition" or "Meat City" necessarily make your summer playlist? Your mileage may vary. However, a solid handful of songs you may have written off due to murky sonics are excellent Lennon.

With a proper mix, "Aisumasen (I'm Sorry)" absolutely soars — it's Lennon's slow-burning, Smokey Robinson-style mea culpa to Yoko Ono. "Bring On the Lucie (Freda Peeple)" has a rickety, communal "Give Peace a Chance" energy — and in some ways, it's a stronger song than that pacifist classic.

And on side 2, the mellow, ruminative "I Know (I Know)" and "You Are Here" sparkle — especially the almost Mazzy Star-like latter tune, with pedal steel guitarist "Sneaky" Pete Kleinow (of Flying Burrito Brothers fame) providing abundant atmosphere.

And, of course, the agreed-upon cuts are even better: "Mind Games" sounds more celestial than ever. And the gorgeous, cathartic "Out the Blue" — led by David Spinozza's classical-style playing, with his old pal Paul McCartney rubbing off on the melody — could and should lead any best-of list.

The Performances Are Killer

Part of the fun of Mind Games: The Ultimate Collection is realizing how great its performances are. They're not simply studio wrapping paper; they capture 1970s New York's finest session cats at full tilt.

Those were: Kleinow, Spinozza, keyboardist Ken Ascher, bassist Gordon Edwards, drummer Jim Keltner (sometimes along with Rick Marotta), saxophonist Michael Brecker, and backing vocalists Something Different.

All are blue-chip; the hand-in-glove rhythm section of Edwards and Keltner is especially captivating. (Just listen to Edwards' spectacular use of silence, as he funkily weaves through that title track.)

The hardcover book included in Mind Games: The Ultimate Collection is replete with the musicians' fly-on-the-wall stories from that week at the Record Plant.

"You can hear how much we're all enjoying playing together in those mixes," Keltner says in the book, praising Spinozza and Gordon. "If you're hearing John Lennon's voice in your headphones and the great Kenny Ascher playing John's chords on the keys, there's just no question of where you're going and how you're going to get there."

It Captures A Fascinating Moment In Time

"Mind Games to me was like an interim record between being a manic political lunatic to back to being a musician again," Lennon stated, according to the book. "It's a political album or an introspective album. Someone told me it was like Imagine with balls, which I liked a lot."

This creative transition reflects the upheaval in Lennon's life at the time. He no longer had Phil Spector to produce; Mind Games was his first self-production. He was struggling to stay in the country, while Nixon wanted him and his message firmly out.

Plus, Lennon recorded it a few months before his 18-month separation from Ono began — the mythologized "Lost Weekend" that was actually a creatively flourishing time. All of this gives the exhaustive Mind Games: The Ultimate Collection historical weight, on top of listening pleasure.

"[It's important to] get as complete a revealing of it as possible," Stevens, who handled the Raw Studio Mixes, tells GRAMMY.com. "Because nobody's going to be able to do it in 30 years."

John Lennon and Yoko Ono in Central Park, 1973. Photo: Bob Gruen

Moments Of Inspired Weirdness Abound

Four seconds of silence titled the "Nutopian International Anthem." A messy slab of blues rock with refrains of "Fingerlickin', chicken-pickin'" and "Chickin-suckin', mother-truckin'." The country-fried "Tight A$," basically one long double entendre.

To put it simply, you can't find such heavy concentrates of Lennonesque nuttiness on more commercial works like Imagine. Sometimes the outliers get under your skin just the same.

It's Never Sounded Better

"It's a little harsh, a little compressed," Stevens says of the original 1973 mix. "The sound's a little bit off-putting, so maybe you dismiss listening to it, in a different head. Which is why the record might not have gotten its due back then."

As such, in 2024 it's revelatory to hear Edwards' basslines so plump, Keltner's kick so defined, Ascher's lines so crystalline. When Spinozza rips into that "Aisumasen" solo, it absolutely penetrates. And, as always with these Lennon remixes, the man's voice is prioritized, and placed front and center. It doesn't dispose of the effects Lennon insecurely desired; it clarifies them.

"I get so enthusiastic," Ascher says about listening to Mind Games: The Ultimate Collection. "I say, 'Well, that could have been a hit. This could have been a hit. No, this one could have been a hit, this one." Yes is the answer.

Photo: Archive Photos/Getty Images

list

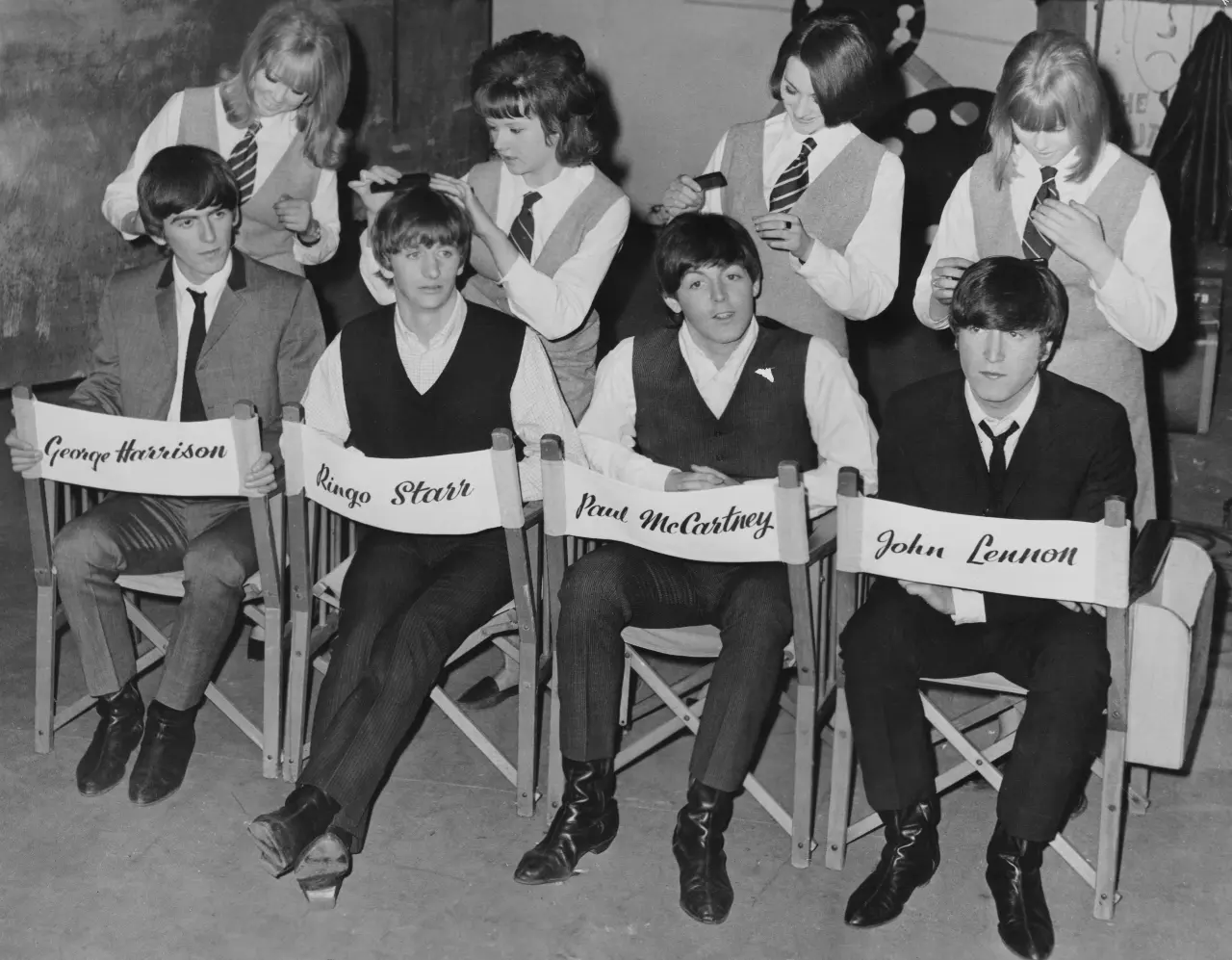

'A Hard Day's Night' Turns 60: 6 Things You Can Thank The Beatles Film & Soundtrack For

This week in 1964, the Beatles changed the world with their iconic debut film, and its fresh, exuberant soundtrack. If you like music videos, folk-rock and the song "Layla," thank 'A Hard Day's Night.'

Throughout his ongoing Got Back tour, Paul McCartney has reliably opened with "Can't Buy Me Love."

It's not the Beatles' deepest song, nor their most beloved hit — though a hit it was. But its zippy, rollicking exuberance still shines brightly; like the rest of the oldies on his setlist, the 82-year-old launches into it in its original key. For two minutes and change, we're plunged back into 1964 — and all the humor, melody, friendship and fun the Beatles bestowed with A Hard Day's Night.

This week in 1964 — at the zenith of Beatlemania, after their seismic appearance on "The Ed Sullivan Show" — the planet received Richard Lester's silly, surreal and innovative film of that name. Days after, its classic soundtrack dropped — a volley of uber-catchy bangers and philosophical ballads, and the only Beatles LP to solely feature Lennon-McCartney songs.

As with almost everything Beatles, the impact of the film and album have been etched in stone. But considering the breadth of pop culture history in its wake, Fab disciples can always use a reminder. Here are six things that wouldn't be the same without A Hard Day's Night.

All Music Videos, Forever

Right from that starting gun of an opening chord, A Hard Day's Night's camerawork alone — black and white, inspired by French New Wave and British kitchen sink dramas — pioneers everything from British spy thrillers to "The Monkees."

Across the film's 87 minutes, you're viscerally dragged into the action; you tumble through the cityscapes right along with John, Paul, George, and Ringo. Not to mention the entire music video revolution; techniques we think of as stock were brand-new here.

According to Roger Ebert: "Today when we watch TV and see quick cutting, hand-held cameras, interviews conducted on the run with moving targets, quickly intercut snatches of dialogue, music under documentary action and all the other trademarks of the modern style, we are looking at the children of A Hard Day's Night."

Emergent Folk-Rock

George Harrison's 12-string Rickenbacker didn't just lend itself to a jangly undercurrent on the A Hard Day's Night songs; the shots of Harrison playing it galvanized Roger McGuinn to pick up the futuristic instrument — and via the Byrds, give the folk canon a welcome jolt of electricity.

Entire reams of alternative rock, post-punk, power pop, indie rock, and more would follow — and if any of those mean anything to you, partly thank Lester for casting a spotlight on that Rick.

The Ultimate Love Triangle Jam

From the Byrds' "Triad" to Leonard Cohen's "Famous Blue Raincoat," music history is replete with odes to love triangles.

But none are as desperate, as mannish, as garment-rending, as Derek and the Dominoes' "Layla," where Eric Clapton lays bare his affections for his friend Harrison's wife, Pattie Boyd. Where did Harrison meet her? Why, on the set of A Hard Day's Night, where she was cast as a schoolgirl.

Debates, Debates, Debates

Say, what is that famous, clamorous opening chord of A Hard Day's Night's title track? Turns out YouTube's still trying to suss that one out.

"It is F with a G on top, but you'll have to ask Paul about the bass note to get the proper story," Harrison told an online chat in 2001 — the last year of his life.

A Certain Strain Of Loopy Humor

No wonder Harrison got in with Monty Python later in life: the effortlessly witty lads were born to play these roles — mostly a tumble of non sequiturs, one-liners and daffy retorts. (They were all brought up on the Goons, after all.) When A Hard Day's Night codified their Liverpudlian slant on everything, everyone from the Pythons to Tim and Eric received their blueprint.

The Legitimacy Of The Rock Flick

What did rock 'n' roll contribute to the film canon before the Beatles? A stream of lightweight Elvis flicks? Granted, the Beatles would churn out a few headscratchers in its wake — Magical Mystery Tour, anyone? — but A Hard Day's Night remains a game-changer for guitar boys on screen.

The best part? The Beatles would go on to change the game again, and again, and again, in so many ways. Don't say they didn't warn you — as you revisit the iconic A Hard Day's Night.

Explore The World Of The Beatles

.webp)

5 Reasons John Lennon's 'Mind Games' Is Worth Another Shot

'A Hard Day's Night' Turns 60: 6 Things You Can Thank The Beatles Film & Soundtrack For

6 Things We Learned From Disney+'s 'The Beach Boys' Documentary

5 Lesser Known Facts About The Beatles' 'Let It Be' Era: Watch The Restored 1970 Film

Catching Up With Sean Ono Lennon: His New Album 'Asterisms,' 'War Is Over!' Short & Shouting Out Yoko At The Oscars

Photo: Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

list

6 Things We Learned From Disney+'s 'The Beach Boys' Documentary

From Brian Wilson's obsession with "Be My Baby" and the Wall Of Sound, to the group's complicated relationship with Murry Wilson and Dennis Wilson's life in the counterculture, 'The Beach Boys' is rife with insights from the group's first 15 years.

It may seem like there's little sand left to sift through, but a new Disney+ documentary proves that there is an endless summer's worth of Beach Boys stories to uncover.

While the legendary group is so woven into the fabric of American culture that it’s easy to forget just how innovative they were, a recently-released documentary aims to remind. The Beach Boys uses a deft combination of archival footage and contemporary interviews to introduce a new generation of fans to the band.

The documentary focuses narrowly on the first 15 years of the Beach Boys’ career, and emphasizes what a family affair it was. Opening the film is a flurry of comments about "a certain family blend" of voices, comparing the band to "a fellowship," and crediting the band’s success directly to having been a family. The frame is apt, considering that the first lineup consisted of Wilson brothers Brian, Dennis, and Carl, their cousin Mike Love, and high school friend Al Jardine, and their first manager was the Wilsons’ father, Murry.

All surviving band members are interviewed, though a very frail Brian Wilson — who was placed under a conservatorship following the January death of his wife Melinda — appears primarily in archival footage. Additional perspective comes via musicians and producers including Ryan Tedder, Janelle Monáe, Lindsey Buckingham, and Don Was, and USC Vice Provost for the Arts Josh Kun.

Thanks to the film’s tight focus and breadth of interviewees, it includes memorable takeaways for both longtime fans and ones this documentary will create. Read on for five takeaways from Disney+'s The Beach Boys.

Family Is A Double-Edged Sword

For all the warm, tight-knit imagery of the Beach Boys as a family band, there was an awful lot of darkness at the heart of their sunny sound, and most of the responsibility for that lies with Wilson family patriarch Murry Wilson. Having written a few modest hits in the late 1930s, Murry had talent and a good ear, and he considered himself a largely thwarted genius.

When Brian, Dennis, and Carl formed the Beach Boys with their cousin Mike Love and friend Al Jardine, Murry came aboard as the band’s manager. In many respects, he was capable; his dogged work ethic and fierce protectiveness helped shepherd the group to increasingly high profile successes. He masterminded the extended Wilson family call-in campaign to a local radio station, pushing the Beach Boys’ first single "Surfin’" to become the most popular song in Los Angeles. He relentlessly shopped their demos to music labels, eventually landing them a contract at Capitol Records. He supported the band’s strong preference to record at Western Recordings rather than Capitol Records’ own in-house studio, and was an excellent promoter.

Murry Wilson was also extremely controlling, fining the band when they made mistakes or swore, and "was miserable most of the time," according to his wife Audree.

Footage from earlier interviews with Carl and Dennis, and contemporary comments from Mike Love make it clear that Murry was emotionally and physically abusive to his sons throughout their childhoods. He even sold off the Beach Boys’ songwriting catalog without consulting co-owner Brian, a moment that Brian’s ex-wife Marilyn says he felt so keenly that he took to his bed and didn’t get up for three days.

Murry Wilson was at best a very complicated figure, both professionally jealous of his own children to a toxic degree and devoted to ensuring their success.

"Be My Baby" and The Wrecking Crew Changed Brian Wilson’s Life

"Be My Baby," which Phil Spector had produced for the Ronettes in 1963, launched the girl group to immediate iconic status. The song also proved life-changing for Brian. On first hearing the song, "it spoke to my soul," and Brian threw himself into learning how Spector created his massive, lush Wall of Sound. Spector’s approach taught Brian that production was a meaningful art that creates an "overall sound, what [the listeners] are going to hear and experience in two and a half minutes."

By working with The Wrecking Crew — a truly motley bunch of experienced, freewheeling musicians who played on Spector’s records and were over a decade older than the Beach Boys — Brian’s artistic sensibility quickly emerged. According to drummer Hal Blaine and bassist Carol Kaye, Brian not knowing what he didn’t know gave him the freedom and imagination to create sounds that were completely new and innovative.

Friendly Rivalries With Phil Spector & The Beatles Yielded Amazing Pop Music

According to popular myth, the Beach Boys and the Beatles saw each other exclusively as almost bitter rivals for the ears, hearts, and disposable income of their fans. The truth is more nuanced: after the initial shock of the British Invasion wore off, the two groups developed and maintained a very productive, admiration-based competition, each band pushing the other to sonic greatness.

Cultural historian and academic Josh Kun reframes the relationship between the two bands as a "transatlantic collaboration," and asks, "If they hadn’t had each other, would they have become what they became?" Could they have made the historic musical leaps that we now take for granted?

Read more: 10 Memorable Oddities By The Beach Boys: Songs About Root Beer, Raising Babies & Ecological Collapse

The release of Rubber Soul left Brian Wilson thunderstruck. The unexpected sitar on "Norwegian Wood," the increasingly mature, personal songwriting, all of it was so fresh that "I flipped!" and immediately wanted to record "a thematic album, a collection of folk songs."

Brian found life on the road soul-crushing and terrifying, and was much more content to stay home composing, writing, and producing. With the touring band out on the road, and with a creative fire lit under him by both the Beatles and Phil Spector’s Wall of Sound, he had time to develop into a wildly creative, exacting, and celebrated producer, an experience that yielded the 1966 masterpiece, Pet Sounds.

Pet Sounds Took 44 Years To Go Platinum

You read that right: Pet Sounds was a flop in the U.S. upon its release. Even after hearing radio-ready tracks like "Wouldn’t It Be Nice?" and "Sloop John B" and the ravishing "God Only Knows," Capitol Records thought the album had minimal commercial potential and didn’t give it the promotional push the band were expecting. Fans in the United Kingdom embraced it, however, and the votes of confidence from British fans — including Keith Moon, John Lennon, and Paul McCartney — buoyed both sales and the Beach Boys’ spirits.

In fact, Lennon and McCartney credited Pet Sounds with giving them a target to hit when they went into the studio to record the Beatles’ own next sonically groundbreaking album, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. As veteran producer and documentary talking head Don Was puts it, Brian Wilson was a true pioneer, incorporating "textures nobody had ever put into pop music before." The friendly rivalry continued as the Beatles realized that they needed to step up their game once more.

Read more: Masterful Remixer Giles Martin On The Beach Boys' 'Pet Sounds,' The Beatles, Paul McCartney

Meanwhile, Capitol Records released and vigorously promoted a best-of album full of the Beach Boys’ early hits, Best Of The Beach Boys. The collection of sun-drenched, peppy tunes was a hit, but was also very out of step with the cultural and political shifts bubbling up through the anti-war and civil rights movements of the era. Thanks in part to later critical re-appraisals and being publicly embraced by musicians as varied as Questlove and Stereolab, Pet Sounds eventually reached platinum status in April 2000, 44 years after its initial release.

Dennis Wilson Was The Only Truly Beachy Beach Boy

Although the Beach Boys first made a name for themselves as purveyors of "the California sound" by singing almost exclusively about beaches, girls, and surfing, the only member of the band who really liked the beach was drummer Dennis Wilson.

Al Jardine ruefully recalls that "the first thing I did was lose my board — I nearly drowned" on a gorgeous day at Manhattan beach. Dennis was an actual surfer whose tanned, blonde good looks and slightly rebellious edge made him the instant sex symbol of the group. In 1967, when Brian’s depression was the deepest and he relinquished in-studio control of the band, Dennis flourished musically and lyrically. Carl Wilson, who had emerged as a very capable producer in Brian’s absence, described Dennis as evolving artistically "really quite amazingly…it just blew us away."

Dennis was also the only Beach Boy who participated meaningfully in the counterculture of the late 1960s, a movement the band largely sat out of, largely to the detriment of their image. He introduced the band to Transcendental Meditation — a practice Mike Love maintains to this day — and was a figure in the Sunset Strip and Laurel Canyon music scenes. Unfortunately, he also became acquainted with and introduced his bandmates to Charles Manson. Manson’s true goal was rock stardom; masterminding the gruesome mass murders that his followers perpetrated in 1969 was a vengeful outgrowth of his thwarted ambition.

The Beach Boys did record and release a reworked version of one of Manson’s songs, "Never Learn Not To Love" as a B-side in 1968. Love says that having introduced Manson to producer Terry Melcher, who firmly rebuffed the would-be musician, "weighed on Dennis pretty heavily," and while Jardine emphatically and truthfully says "it wasn’t his fault," it’s easy to imagine those events driving some of the self-destructive alcohol and drug abuse that marked Dennis’ later years.

The Journey From Obscurity To Perennially Popular Heritage Act

The final minutes of The Beach Boys can be summed up as "if all else fails commercially, release a double album of beloved greatest hits." The 1970s were a very fruitful time for the band creatively, as they invited funk specialists Blondie Chaplin and Ricky Fataar to join the band and relocated to the Netherlands to pursue a harder, more far-out sound. Although the band were proud of the lush, singer/songwriter material they were recording, the albums of this era were sales disappointments and represented a continuing slide into uncoolness and obscurity.

Read more: Brian Wilson Is A Once-In-A-Lifetime Creative Genius. But The Beach Boys Are More Than Just Him.

Once again, Capitol Records turned to the band’s early material to boost sales. The 1974 double-album compilation Endless Summer, comprised of hits from 1962-1965, went triple platinum, relaunching The Beach Boys as a successful heritage touring act. A new generation of fans — "8 to 80," as the band put it — flocked to their bright harmonies and upbeat tempos, as seen in the final moments of the documentary when the Beach Boys played to a crowd of over 500,000 fans on July 4, 1980.

While taking their place as America’s Band didn’t do much to make them cool, it did ensure one more wave of chart success with 1988’s No. 1 hit "Kokomo" and ultimately led to broader appreciation for Pet Sounds and its sibling experimental albums like Smiley Smile. That wave of popularity has proven remarkably durable; after all, they’ve ridden it to a documentary for Disney+ nearly 45 years later.

Listen: 50 Essential Songs By The Beach Boys Ahead Of "A GRAMMY Salute" To America's Band

Photo: Rosalind O'Connor/NBC via Getty Images

interview

Behind Leon Michels' Hits: From Working With The Carters & Aloe Blacc, To Creating Clairo's New Album

Multi-instrumentalist turned GRAMMY-nominated producer Leon Michels has had a hand in a wide range of pop and hip-hop music. Read on for the stories behind his smash hits with Norah Jones, Black Thought, Kalis Uchis, Aloe Blacc, and others.

A child of New York’s ultra-niche soul revival scene of the early 2000s, multi-instrumentalist turned producer Leon Michels has had an extensive reach into global pop music. As both producer and session man, Michels has worked with the Carters, Norah Jones, Black Thought, the Black Keys, Kalis Uchis, and Aloe Blacc — to name a few.

He has held to a specific creative vision for more than two decades, first through his heavily sampled El Michels Affair projects and a healthy schedule of releases through Truth & Soul records and later, Big Crown, the label he co-founded with DJ Danny Akalepse in 2016. He runs a studio in upstate New York called the Diamond Mine North, where he does most of his work since relocating from New York City in 2017. He has two GRAMMY nominations to his name, for Mary J. Blige’s Good Morning Gorgeous and Lizzo’s Special.

Trained originally on piano, he took up drums and eventually saxophone through the guidance of his high school music teacher, Miss Leonard. "[She] is actually the person I owe it all to. She started this jazz band when I was in fifth grade, and there's no drummer, so she asked me if I would learn drums," he tells GRAMMY.com. "I did that, and she would give me Duke Ellington cassettes, Sydney Bichet, Johnny Hodges. She would just feed me music."

Daptone Records co-founder Gabe Roth recruited and mentored Michels while he was still in high school, and the teenager soon became a regular touring member of what would become the Dap-Kings, backing singer Sharon Jones during an early run of success in the mid-2000s. " I joined Sharon Jones when it was the Soul Providers. We went on tour in Europe with them. Somehow my parents let me do it. I don't even understand. Gabe came over and sweet-talked them."

Michels left the group in 2006 after seven intense years, wanting to spend more time recording than enduring the grind of touring. His chosen timing caused him to miss out by mere "months" on the group’s recording sessions for Amy Winehouse’s four-time GRAMMY winner Back To Black. Despite what appeared to be a major missed opportunity, he turned his focus to his group El Michels Affair after initial encouragement from the 2005 album Sounding Out The City, released on Truth & Soul, the label he had co-founded.

Finding his inspiration in the intersections of soul and hip-hop, as a fully committed instrumentalist producer, he was able to develop an analog soundscape that quickly caught the ears of artists including Raekwon and other Wu-Tang Clan alumni, with whom he toured in 2008. This led to the follow-up album Enter The 37th Chamber in 2009. Samples from El Michels Affair, including those by Ghostface Killah, Jay-Z, Just Blaze, J. Cole, and Travis Scott quickly proliferated and opened doors. Via the Lee Fields album My World, Michels' work caught the attention of Dan Auerbach, with whom he and his longtime collaborator and bassist Nick Movshon toured from 2010 to 2012.

Producing the Aloe Blacc song "I Need A Dollar" in 2010 further enhanced his credentials and provided the financial stability to allow him to be true to his creative spirit, which he has done successfully over the last decade.

Leon Michels spoke to GRAMMY.com about some key career recordings, including his latest release with singer Clairo.

Clairo – "Sexy to Someone" (Charm, 2024)

I met Clairo almost three years ago. I made a record with her that took three years to complete, which is actually one of the longest stretches I've ever spent on a record.

She’s made two records before this. Her first record, Immunity, came out when she was 19. It's a pop record, and it was very successful. But she's a total music nerd like me. She’s constantly scouring the Internet for music. The way people, especially young people, ingest music these days is just insane. She's got great taste.

Her first record was super successful. She made her second record, Sling, with Jack Antonoff, and it was an ambitious folk record, and a huge departure from her first record. I think it caught her audience off guard, but it was kind of a perfect move because now she can make whatever she wants.

When she came to me, I was excited but slightly confused. What do I do? Because in those situations, you think, well, I need to facilitate a successful pop record, but she just wanted all the weird s—.

It’s this cool mix of pop elements, but some of the music sounds like a Madlib sample. All of it is steeped in pretty cool references and older music, but her perspective is a 25-year-old’s, and she’s an incredible songwriter. It's a really cool mix.

Norah Jones - "Running" (Visions, 2024)

Norah used to hit up me and Dave Guy, trumpet player in the Menahan Street Band and the Roots, if she needed horns.

As we were coming out of the pandemic, she hit me up and wanted to make some music. We made a few songs and then after that, she asked me to produce her Christmas record, which was super fun because I've never listened to Christmas music. I started to enjoy it, which was weird because I had thought I hated Christmas music. I mean, once you start to dig for Christmas records, pretty much all of your favorite artists have them. I was listening to Christmas music from March to October the entire year.

After that, we made Visions, which is all original stuff. Norah's just so talented. Her musicianship is actually some of the most impressive I've ever seen or worked with. She's so good that when I play with her, I get intimidated and I forget basic harmony and music theory!

We cut that record, mostly just the two of us. There's a couple of songs where we got a band, but most of it was in my upstate studio. She would just come over from nine to three. She would come after she dropped her kids at school and then have to leave to pick them up. It was super fun to make, essentially just jamming all day.

[Overall] it’s not a huge departure for Norah, but sonically it is a departure, and it's got this very loose, "un-precious" quality. That's maybe a little different from her other stuff.

"Running" was her choice as a single. When it comes to singles — the songs that have actually been most successful — I've wanted to take those off the record. I have no idea what's going to be the hit or not.

Black Thought - "Glorious Game" (Glorious Game, 2023)

That was a total pandemic record — at the start of the pandemic when everyone was completely locked in, we had no idea what was going on.

Black Thought texted me out of the blue, and I think he was just trying to stay busy. So he just said, "Can you send me songs?" I sent him maybe two songs and then he sent back finished verses three or four hours later. Most of that record was just me sending him s— and him sending it back, and then going like that. We had probably 20 songs.

The time I did spend in the studio with him was, he's a total savant. He sits there while you're playing a song, and it kind of looks like he's on Instagram or f—ing around, you know what I mean? Does this guy even like this song? And then 45 minutes later, he’ll be like "Aight, ready." And he goes in there and, and he'll rap four pages of lyrics in one take. It's insane. He remembers everything; we'll do a song and then three years later, he'll have to redo it, but he'll know the lyrics from memory.

There's a couple of things that I figured out on that record. One: The thing I love about sampled hip-hop production the most is it's almost always pitch-shifted, which makes a giant difference in the sound. And if the piano has decay or vocals have vibrato, when you pitch it up, it becomes something that is so uniquely hip-hop. The second thing was, with hip hop, one of the best parts about sampling is the choices a producer has to make when they are limited to chopping a two-track mix. If you have multi-tracks, there are too many options.

I think that record resonated with people who are hip-hop aficionados who really love the art of emceeing.

Aloe Blacc - "I Need A Dollar" (Good Things, 2010)

We had just recorded the Lee Fields record, My World. Eothen Alapatt, who used to be a label manager at Now Again, was a friend of mine. [Jeff Silverman and I] started Truth & Soul, but we had no infrastructure. We thought My World would have a bigger reach if Stones Throw took care of the press and distribution. And so Eothen said "Yeah, we can do that, but instead of paying us, just make a record with this artist we have, Aloe Blacc."

I had no idea who he was. And so that was the business deal. We didn't get paid for the record initially. The payment was that they were going to promote Lee Fields record for us. So [Aloe] came to New York, and I did it with my partner at the time, Jeff Silverman, also Nick Movshon, who played on the entire record.

He wanted to do this Bill Withers thing. "I Need A Dollar" was probably my least favorite song on the record. I think I have this aversion to anything that's slightly cheesy, but I've gotten better at it. But at the end of the day, it's just a good song. It got picked up as the theme song to an HBO pilot called "How To Make It In America." And then, it just blew up in Europe. It was No. 1 everywhere. But it never hit in America.

It kind of set me off on a weird path for a minute, because I got a taste of success. And made some poor career decisions. I tried to a do lot of songwriting sessions with strangers. It was maybe four years until I decided to just make El Michels Records.

The Carters - "SUMMER" (EVERYTHING IS LOVE, 2018)

At the time, I was making these sample packs and sending them out to producers. One of them was this slow jam, and so the producers called me up and said "We used one of your samples. It's for a giant artist. We can't tell you who it is. You have to approve it now. And you can't hear it, but it's going to change your life." That’s what they kept saying to me. Then they said "It's coming out in two weeks."

So I figured they used one of my samples and chopped it up and did their thing to it. And so when the record came out, it was Beyoncé and Jay-Z. It was the first track on that record they did together, the Carters. And it was mostly just my original sample with some new bass and string section. So basically it was just Beyoncé and Jay-Z over an El Michael's Affair track. The track was called "Summer," and my original never came out.

So just hearing Beyoncé, hearing these giant pop voices that I associate with absolute hits, over my song, that was pretty cool.

Liam Bailey - "Dance With Me" (Zero Grace, 2023)

Me and him just have a very crazy chemistry when it comes to music, because it all happens super fast and with very little thought. Sometimes I'll listen to Liam's stuff, and I actually don't know how we did it. That is actually the goal. That’s why Lee "Scratch Perry" is the greatest producer of all time, because he could access that instant input, instant output type of creativity. It just passes through him and then it's on the record. Making music with Liam is like that; I'll make some instrumental, or I'll have an idea and then he'll freestyle lyrics one or two times.

To me, it sounds gibberish, but then he'll go through it and change one or two words and all of a sudden has this crazy narrative, and it's about his childhood [for example]. When I’ve worked with him, he has this same process where it's just kind of "hand to God" s—, just let it happen. I was trying to make something the way Jamaicans did, [like] that brand of Jamaican soul from the mid-'60s.

Brainstory - "Peach Optimo" (Sounds Good, 2024)

I met those guys through Eduardo Arenas, who's the bass player from Chicano Batman, and he had recorded a couple of demos from them. And they had one song in particular that really caught my attention, which made it onto their first record called "Dead End."

They’re three jazz kids. Their dad was a gospel singer and loved soul and Stevie Wonder. So they grew up on all that stuff as well. Producing a band like Brainstory is super easy, because they rehearse all the time. Most of their songs are written; all I have to do is maybe shuffle around sections or just essentially cut stuff out. Because a lot of times when bands write music and rehearse every day, they just love to play, so sections are endless.

I'll…have a sound in mind for the record, some reference for me and the engineering hands to kind of work from. And in the case of Sounds Good, the reference for the whole sound of the record was that this is Gene Harris song called "Los Alamitos Latin Funk Love." This is kind of the vibe of the entire record. We just cut that record over the course of a year, but it was two sessions that were maybe six days each.

Kevin is the main vocalist and he's amazing. He can do that sweet soul background stuff perfectly. And when he does [his own] background vocals, it's this thing that not a lot of people can do where he changes his personality. So he becomes three different people. Then the background sounds like an actual group.