Photo: Bradley Quinn

interview

Living Legends: Van Morrison On New Album 'Moving On Skiffle,' Communing With His Roots & Reconnecting With Audiences

"It's in the backdrop of everything I've ever done," the two-time GRAMMY winner says of the primordial soup of skiffle, a scrappy, street-level genre formative to 1960s folk and rock in the United Kingdom.

Living Legends is a series that spotlights icons in music still going strong today. This week, GRAMMY.com presents an interview with two-time GRAMMY winner Van Morrison, one of the most influential singers, songwriters and bandleaders of the 20th century, who codified "Celtic soul" for a generation. His new album, Moving on Skiffle, is available now.

These days, Van Morrison tends to be in the news for reasons that have little to nothing to do with music.

His irascibility toward the World Economic Forum, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, et al has been well documented — as have his public clashes with federal governments over pandemic lockdown policies. Sure, such policies have a lot to do with his livelihood; for a time, they precluded live performances for the master bandleader. In response, he released a string of protest singles with Eric Clapton: "The Rebels," "Stand & Deliver," "This Has Gotta Stop"; the topic made its way into his solo music as well. Robin Swann, the Northern Ireland Minister of Health, lambasted him as "dangerous" for his position on lockdowns; he cheekily responded with a song of the same name.

As such, the resultant discourse — and controversy — has lately earned him more attention as a political agitator than a still-vital musician. Which can threaten to obfuscate the ocean of output (or as he idiosyncratically calls it, "product") Morrison's released in the past decade and change.

That's a shame, because his recent run of albums has been fantastic; at 77, the two-time GRAMMY winner's talents remain essentially undimmed. 2016's autumnal Keep Me Singing was a treasure; so was You're Driving Me Crazy, his 2018 album with the late Hammond B-3 titan Joey DeFrancesco. Others, too, like 2018's rollicking The Prophet Speaks, which also featured DeFrancesco, and 2019's earthy Three Chords and the Truth are mightily satisfying as well.

His last two, 2021's Latest Record Project, Vol. 1 and 2022's What's It Gonna Take?, were charged with dark, sardonic energy as Morrison took shots at the government, marking the seventh or eighth Van's Mad epoch in his discography.

Despite traces of said animus at the Man, everything about his latest album, Moving on Skiffle, out Mar. 10, signals a new beginning — from its premise (it's all from the skiffle songbook, reimagined to various degrees) to its sound (simple, breezy, ebullient) to its title, suggestive of dusting off and forging ahead.

In this edition of Living Legends, GRAMMY.com sat down with Morrison to discuss the making of Moving on Skiffle, getting back onstage after music ground to a halt, and why the folk-oriented genre of yore remains fundamental to everything he's made in its wake.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

Skiffle loomed so large in the music flowing out of the UK in the 1960s — among so many other artists, it birthed the Beatles, the Hollies and, from what I understand, you. Can you lay the groundwork as per your relationship to this beautiful mishmash of an artform?

"Mishmash," yeah. I don't know if you've done any history research, but it basically started with: Lead Belly, Woody Guthrie, Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee, and Josh White got together to make this kind of music. Someone called it "skiffle." It was pre- the British kind of skiffle. It was forgotten about in the U.S., but it made its way to the U.K. and was incorporated into this kind of music.

It was basically a mixture of mostly American folk music and Black American folk music, stemming from Lead Belly and a guy in the U.K. called Lonnie Donegan. He came out with a record ["Rock Island Line"] and it was a big hit. So, that started the ball rolling.

How did it come into your life?

Well, because I heard it. It was all over the radio. There were programs that had people on Saturday mornings, and Lonnie Donegan was on the radio quite a bit. I got hold of the 78 r.p.m. with "Rock Island Line," and "John Henry" was on the B-side. But it was all over the place then, sometime in the '50s.

**When I listen to Moving on Skiffle, I get the sense that these songs have been floating around your consciousness through all your eras, phases and decades. How did you boil down the skiffle songbook into this curated sequence of 23 tunes?**

Well, with a lot of work.

I'd like to home in on a few tunes that stand out to me. Can you talk about your connection to "Sail Away Ladies"?

Yeah, well, I mean, again, it's one of those songs that's been in various versions, and it's an old song. I think it's from the Appalachians or something. It's also called "Don't You Rock Me Daddy-O." It came out as that. It came out as "Sail Away Ladies." There's, like, hundreds of versions of this song, you know? So, it's just part of the genre.

Another favorite is "Gypsy Davy," a Scottish ballad that runs so deep in the tradition, from what I was reading. My wife, who grew up on Celtic music, immediately recognized it. Can you talk about what appeals to you about that one?

Well, it's the same thing; it was part of the repertoire. I did it in a band I was in in 1963. It was also part of the folk memory, and it's also been under various titles. It's been done as "Black Jack Davy." In fact, there's a book that goes into all the history of that song, and other songs. I forget the title right now.

"Gov Don't Allow" also resonates with me. I connect to its anti-authoritarian message, which feels harmonious with some of the messages in your recent albums.

Well, that comes from the old song "Mama Don't Allow." I just changed the lyrics. It's what it says in the song. If you follow the lyrics, the lyrics can explain it better than I can right now.

Lastly, I want to bring up "Green Rocky Road." I was pretty blown away by it — it's nine minutes long. I've always known and loved it — Donovan and Tim Hardin's version in particular — but you brought it to a completely new space.

Again, it was one of those songs where there's loads of different versions of it. But I just stretched it out and made it longer, and added some lyrics. I put a few chords in it that I haven't heard before.

When you sing these songs live or in the studio, how does it make you feel to make these new connections with tunes you've known for 60-plus years?

[Slightly taken aback] How does it feel!

Yeah.

Well, it feels like the word you just used: connecting. But it's in the backdrop of everything I've ever done. I mean, this is what I came out of.

There was a book that came out in the UK when I was a kid called American Folk Guitar, by Alan Lomax and Peggy Seeger. Lomax and Seeger were both living in the UK then, and they were actually in a skiffle group themselves. So, it's all connected. This is where I'm coming from. These are the roots.

This is a 23-track album, and you've made so many in recent memory. More than that, they're really good. I listen to Three Chords and the Truth and Latest Record Project, Vol. 1 all the time. I feel like you don't get enough credit for bringing quality and quantity. What's been galvanizing you to make so much music lately?

Well, just 'cause I can do it, and the obvious reason is because of [chuckles] the obvious thing we're staring in the face, this plandemic that stopped the gigs.

You couldn't do gigs. Live gigs were banned. I don't know if you know about all this, but you couldn't travel. It was a couple of years where you really couldn't do gigs. So, the other thing is writing and recording.

It must have taken an emotional toll on you to not be able to connect with audiences. But I can feel that release in this music.

Yeah, yeah, yeah.

*Van Morrison performing live. Photo: Bradley Quinn*

Now that you've taken a trip through the skiffle songbook, what's next for you?

Well, there's other product, but it's pointless to talk about it now, because I don't know when it's going to come out. But if and when it comes out, we could do another interview about that, because there's so much stuff I have. I couldn't tell you when the next one's going to be, but we'll let you know when we put it out.

When I think of the throughline of your entire career, I see you as the consummate bandleader. Your interplay and telepathy with a large ensemble seems central to your art in some ways. Are there any musicians on Moving on Skiffle that you'd like to pay a token of appreciation to?

Well, all of them, because they work really well. Especially on this product, this album. There's Colin Griffin on drums, Pete Hurley on bass, Stuart McElroy on piano, Richard Dunn on organ, Dave Keary on guitar. Plus, there's backup singers like Crawford Bell, Dana Masters and Jolene O'Hara.

Don't forget "Sticky" Wicket on washboard! All these people need to be commended for doing such a good job.

Las Cafeteras

Photo credit: JP

news

Positive Vibes Only: Las Cafeteras Serve Up An Empowering Performance Of Woody Guthrie's "This Land Is Your Land"

Chicano band Las Cafeteras deliver an electric performance of Woody Guthrie's "This Land Is Your Land," in the latest edition of Positive Vibes Only

Las Cafeteras makes sure that the latest edition of Positive Vibes Only captures your attention from start to finish.

In their performance of Woody Guthrie's "This Land is Your Land," Hector Paul Flores and Denise Carlos get the party started with an exchange of jolting gritos (long shouts, deeply rooted in Mexican history), and the Chicano band never lets up from there.

The irresistible energy coarsing through the band's instrumentation and background ad-libs add oomph to the classic song's declaration that "this land was made for you and me."

Watch below to see the Chicano sextet light up the stage with their infectious energy and thought-provoking performance of "This Land Is Your Land."

Their cover of "This Land Is Your Land" appeared on the East Los Angeles band's 2017 album Tastes Like L.A..

Check out more episodes of Positive Vibes Only below.

Woody Guthrie In The 21st Century: What Does The Folk Hero Mean To Contemporary Musicians?

Woody Guthrie

Photo: CBS via Getty Images

news

Woody Guthrie In The 21st Century: What Does The Folk Hero Mean To Contemporary Musicians?

Despite being gone for more than half a century, Woody Guthrie remains exceptionally relevant to millions—including these Americana musicians, who banded together for the tribute album 'Home In This World'

From California to the New York island, each city, town, and corridor of America tends to grow its own distinctive type of artist. What about Oklahoma, where Woody Guthrie came up in the tiny town of Okemah?

"Oklahoma culture is really interesting because it's not the South, and it's not the Midwest," singer/songwriter Parker Millsap—a proud Okie himself—tells GRAMMY.com. "It's really new; it wasn't a state until 1907. So it's a unique place because it's in the middle of everything but also far away from everything."

In the 21st century, this sums up Guthrie, who died in 1967. Born 99 years ago, he cataloged the plight of Dust Bowl migrants and caught accusations of Communism—both concepts that tend to molder in history books. While its meaning remains contested, "This Land Is Your Land" remains somewhat frozen in amber as a classroom singalong. Bob Dylan, Bruce Springsteen, and the Byrds have long since given his other classics, like "Pretty Boy Floyd" and "Ain't Got No Home," their own spin.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//VSehQKKeKNE' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Despite all this, Guthrie keeps bobbing to the surface, whether it be reports of his tussling with a certain landlord named Trump or Lady Gaga's cover of you-know-what at the Super Bowl. But as a handful of contemporary artists attest, these songs could have been written this morning.

Home In This World, a track-by-track remake of his 1940 Dust Bowl Ballads album, arrived September 10, featuring modern Americana acts like Waxahatchee ("Talking Dust Bowl Blues"), Watkins Family Hour ("Blowin' Down This Road"), and Swamp Dogg ("Dust Bowl Refugee"). The point? All these decades later, class struggles, economic pain, and the rising tide of neo-fascism remain global enemies to reckon with—and sing about.

Woody Guthrie. Photo: John Springer Collection/Corbis via Getty Images

Unlike other mid-20th-century musical icons like Elvis Presley and Frank Sinatra, Guthrie didn't have a "music career" in the way we understand it today—both in its cyclical nature and that stars didn't usually pal around with leftist activists and union organizers.

Instead, he was more of a documentarian—hitchhiking, riding the rails, hanging out with roustabouts and ne'er-do-wells, and generally soaking up the struggles of ordinary people during the Dust Bowl.

Most crucially, he externalized these experiences, churning out volumes of songs, poems, and prose. (To say nothing of his brilliant, partly fictionalized 1943 memoir, Bound For Glory.) Billy Bragg's and Wilco's Mermaid Avenue, Vols. 1 and 2, which set previously unheard lyrics to music, crucially unfroze him from his political context, demonstrating his diverse moods, feelings, and interests. All of this adds up to an unadulterated, livewire artist—in other words, the real deal.

Parker Millsap. Photo: Tim Duggan

"He stood for people, not money and rock stardom," Millsap explains. "Music stardom has been associated with a certain corporatism, and Woody was doing his thing before that took off with Elvis and the Beatles." So perhaps Guthrie remaining commercially unfettered—and, as such, free to express anything he wanted—is partly why his music has endured.

But this alone doesn't guarantee timelessness. To earn that adjective, Guthrie would need to tackle specific, evergreen problems. Case in point: "Vigilante Man," which Millsap covered for Home In This World. "Why does a vigilante man/ Carry that sawed-off shotgun in his hand?" Guthrie asks in the song. "Would he shoot his brother and sister down?"

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//RX2FnGNDz5c' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

"I just think it's powerful and resonates with the rising consciousness of police power and what that entails, and what should and shouldn't be allowed," Millsap says. "When police kill people without giving them the right to trial, they're playing the judge; they're playing the jury; they're playing the prosecutor. They're taking the law in their own hands beyond what they're allowed, and so, to me, that makes them vigilantes."

"I thought: If he was alive today, there's no way he wouldn't have written songs about Breonna Taylor and George Floyd and the countless others who have fallen victim to police brutality," he continues. Because of this, Millsap took the liberty of adding new verses, casting "Vigilante Man" in the light of the Black Lives Matter movement.

Lillie Mae. Photo: Misa Arriaga

As for Nashville singer/songwriter Lillie Mae, Guthrie's work's sense of unchecked social injustice resonates with her, especially in this era of layoffs, lockdowns, and federal stimulus checks.

"If these songs were popular in the Depression, it seems like a more modern version of that," she tells GRAMMY.com. "We're absolutely in—not a similar circumstance, but hardships left and right for everyone. I think that is probably very similar to what was at the time when he was writing these songs. I don't think they could have picked a better time to put out a project."

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//CC2jFbuf0Mc' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

For this project, Mae picked "Tom Joad, Pt. 2," about a homicide parolee who finds his family has been driven from their farm. He and "Preacher Casey" flee with the Joad family to a "jungle camp," where a deputy sheriff shoots an innocent woman in the back—and Casey lays him flat for his trouble. Instead of being exonerated for self-defense, Casey is hauled to jail and escapes—and "vigilante thugs" ultimately corner him and gun him down, too.

"They killed the good guy. Like, the good guy's standing over the bad guy, and then they wipe out the good guy," Mae says with a hint of astonishment. "That is very accurate, still in today's world. That happens all day long, every day."

"He was obviously a brilliant human being," she continues. "What a cool gift—to receive things he saw and word them in ways that resonate with so many people. He's a great songwriter who, for good reason, is standing up with the test of time."

John Paul White. Photo: Alysse Gafkjen

John Paul White, a Muscle Shoals native who used to be one half of the GRAMMY-winning folk duo the Civil Wars, admits he's a man out of time. A devotee of songwriter's songwriters like Tom T. Hall and Don Schlitz, White loves story songs—which, he freely admits, are no longer a popular mode of expression.

"I've always been a sucker for those," he tells GRAMMY.com. "I gravitate toward discernible storylines, front to back." This description exactly describes the Guthrie outlaw classic "Pretty Boy Floyd," and that's why White chose it for this collection: A great yarn never goes out of style.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//EIbrIRhpvDo' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Another Guthrie lesson that resonates with White is how the legendary songwriter passed the torch to a generation—specifically, the time Dylan visited Guthrie at Brooklyn State Hospital when he was dying of Huntington's disease. Just as Guthrie had learned from the Western artists he loved as a boy—and the migrant workers he learned from on the road—he, in turn, gave numberless folkies in his wake a song, a conscience, and a lineage to belong to.

"It's like a movie," White says. "I think of those things, and I think: I should do the same thing. I should seek out my heroes and the people that mentored me without knowing it. I should go to their bedside and learn all I can and make sure they know they're revered. I don't do a very good job of that."

Perhaps Guthrie's son, Arlo—of "Alice's Restaurant Masacree" fame—put it best in a recent tweet: "Seems like the longer he's gone the more popular he gets. Joking aside, he left an indelible mark on me and a big chunk of the world." Granted, Guthrie is rarely celebrated in the mainstream like other figures of his era. But everyone who picks up a guitar and pen has to reckon with him at some point.

And ultimately, that's what this collection proves. To the average person, maybe Guthrie is "far away from everything," as Millsap said of his native state. But music fans who understand what's really going on—that history is currently rhyming—also grasp that Guthrie remains completely relevant, aged like wine, right here in the mix. He's at home in this world, just like he was in the last one.

Here's What Went Down At Bob Dylan's Mysterious "Shadow Kingdom" Livestream Concert

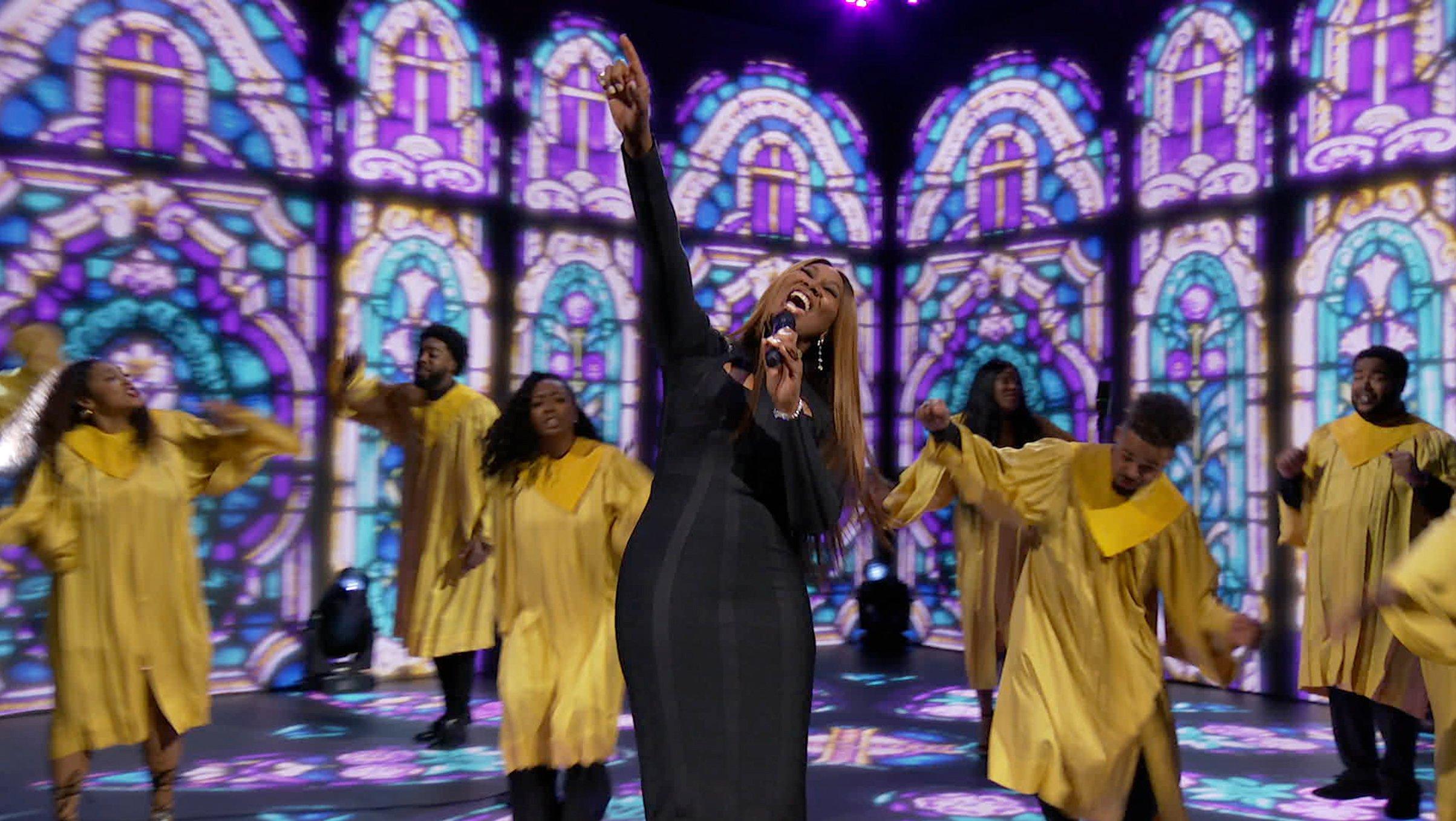

Yolanda Adams

Photo courtesy of CBS

news

Here's What Went Down At "A GRAMMY Salute To The Sounds Of Change"

Featuring performances by stars from Patti LaBelle to Andra Day to Gladys Knight, "A GRAMMY Salute To The Sounds Of Change" was a decades-spanning celebration of the songs that both reflect and alter the course of social justice history

When Woody Guthrie wrote "This Land is Your Land," he certainly understood he was expressing something important to the world. Ditto John Lennon with "Imagine" and Marvin Gaye with "What's Going On." But could any of them have known we'd still be singing them in 2021? That amid the racial nightmares of George Floyd's killing and the anti-Asian violence that just battered Georgia, we'd return to the well of songs from 50 or more years ago for healing?

Welcome to "A GRAMMY Salute To The Sounds Of Change," a special that solemnly, respectfully paid homage to the songs that altered the course of social-justice history. But the event, which the hip-hop heavyweight Common hosted, didn't just focus on the great tracks of the 20th century; it filtered them through the musical luminaries of the 21st.

A mix of archival performances and COVID-safe new ones, the special succeeded in showing that our modern horrors aren't so new at all—and that throughout history, brave men and women have risen to address the changing tides of history in song. Thus, the young guard (LeAnn Rimes, Chris Stapleton and Andra Day) rubbed shoulders with the old (Gladys Knight, Patti LaBelle), showing these well-worn standards still emanate transformative power.

<blockquote class="twitter-tweet"><p lang="en" dir="ltr">WEST COAST, your turn!<br><br>Hosted by three-time GRAMMY winner <a href="https://twitter.com/common?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw">@Common</a>, A <a href="https://twitter.com/hashtag/GRAMMYSalute?src=hash&ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw">#GRAMMYSalute</a> To The <a href="https://twitter.com/hashtag/SoundsOfChange?src=hash&ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw">#SoundsOfChange</a> will spotlight the iconic songs that inspired social change and left an everlasting imprint on history. <br><br>WATCH NOW on <a href="https://twitter.com/CBS?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw">@CBS</a>. ✨ <a href="https://t.co/JBedRxTvnJ">pic.twitter.com/JBedRxTvnJ</a></p>— Recording Academy / GRAMMYs (@RecordingAcad) <a href="https://twitter.com/RecordingAcad/status/1372397350317006851?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw">March 18, 2021</a></blockquote> <script async src="https://platform.twitter.com/widgets.js" charset="utf-8"></script>

It's no accident that Common was at the helm of "A GRAMMY Salute To The Sounds Of Change"; check out his socially conscious 1999 classic Like Water For Chocolate if you're curious about how he fits into this puzzle. (Not to mention his poignant performance of "Glory," the theme song to the 2014 film Selma, with John Legend at that year's GRAMMY Awards show.)

After the MC's dignified introduction, the night kicked off with a nocturnal version of John Lennon's "Imagine" by the pearl-covered singer Cynthia Erivo. She ended the rendition with a hair-raising vamp, surrounded by projected imagery of placards reading things like "Close The Camps" and "Unjustified War Is Criminal."

Country titan Chris Stapleton then performed Louis Armstrong's "What a Wonderful World," showing how the old chestnut easily transmutes into a variety of American idioms. (To this point: check out Jon Batiste's melancholic version from 2018's Hollywood Africans.)

In a tonal 180, LeAnn Rimes then performs Loretta Lynn's saucy (and at the time, unspeakably scandalous) 1975 ode to birth control, "The Pill." Her masked, punked-up backing band showed us how the tune essentially invented Bikini Kill. The womens' liberation theme continued with R&B great Patti LaBelle laying into Lesley Gore's "You Don't Own Me."

<blockquote class="twitter-tweet"><p lang="en" dir="ltr">? A powerful song. A powerful voice. <br><br>Patti LaBelle (<a href="https://twitter.com/MsPattiPatti?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw">@mspattipatti</a>) performs <a href="https://twitter.com/hashtag/LeslieGore?src=hash&ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw">#LeslieGore</a>'s "You Don't Own Me" during "A <a href="https://twitter.com/hashtag/GRAMMYSalute?src=hash&ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw">#GRAMMYSalute</a> To The <a href="https://twitter.com/hashtag/SoundsOfChange?src=hash&ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw">#SoundsOfChange</a>". ✨<br><br>Watch now on <a href="https://twitter.com/CBS?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw">@CBS</a> or <a href="https://twitter.com/paramountplus?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw">@paramountplus</a>! <a href="https://t.co/M7HBLYmAbh">pic.twitter.com/M7HBLYmAbh</a></p>— Recording Academy / GRAMMYs (@RecordingAcad) <a href="https://twitter.com/RecordingAcad/status/1372360515322798082?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw">March 18, 2021</a></blockquote> <script async src="https://platform.twitter.com/widgets.js" charset="utf-8"></script>

That performance segued into even heavier territory with a version of the "Strange Fruit" by Andra Day—who recently won a Golden Globe for her performance in 2021's The U.S. vs. Billie Holiday. She crooned the anti-lynching classic in a crepuscular, green-screened forest. Showing that times tragically haven't changed in certain respects, "Strange Fruit" segued into Leon Bridges' "Sweeter," a response to George Floyd, featuring Terrace Martin on blazing saxophone.

<blockquote class="twitter-tweet"><p lang="en" dir="ltr">"What's Going On" performed by ?:<br><br>? <a href="https://twitter.com/MsGladysKnight?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw">@MsGladysKnight</a> <br>? <a href="https://twitter.com/ihoughton?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw">@ihoughton</a> <br>? <a href="https://twitter.com/SheilaEdrummer?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw">@sheilaEdrummer</a> <br>? <a href="https://twitter.com/DSmoke7?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw">@dsmoke7</a> <br><br>Tune in to "A <a href="https://twitter.com/hashtag/GRAMMYSalute?src=hash&ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw">#GRAMMYSalute</a> To The <a href="https://twitter.com/hashtag/SoundsOfChange?src=hash&ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw">#SoundsOfChange</a>" right now on <a href="https://twitter.com/CBS?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw">@CBS</a> and <a href="https://twitter.com/paramountplus?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw">@paramountplus</a>! <a href="https://t.co/v4sQzasc5W">pic.twitter.com/v4sQzasc5W</a></p>— Recording Academy / GRAMMYs (@RecordingAcad) <a href="https://twitter.com/RecordingAcad/status/1372366401357381643?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw">March 18, 2021</a></blockquote> <script async src="https://platform.twitter.com/widgets.js" charset="utf-8"></script>

These issues represent mere facets of human disharmony. But Marvin Gaye's intellect and imagination were keen enough to not only grasp that vastness but channel it into a song for everyone. Enter seven-time GRAMMY winner Gladys Knight, who stepped on stage to perform the immortal "What's Going On" with Sheila E. on percussion, Israel Houghton on guitar, D Smoke on keys and musical director Adam Blackstone on bass.

"Hi, Marvin!" Knight crowed at the outset. "I miss you so much. I love your music—the way you write, the way you sing, the whole thing. You touch my spirit every time you sing a song."

<blockquote class="twitter-tweet"><p lang="en" dir="ltr">GRAMMY nominee <a href="https://twitter.com/ericchurch?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw">@ericchurch</a> covers <a href="https://twitter.com/hashtag/EdwinStarr?src=hash&ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw">#EdwinStarr</a>'s "War" right now during "A <a href="https://twitter.com/hashtag/GRAMMYSalute?src=hash&ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw">#GRAMMYSalute</a> To The <a href="https://twitter.com/hashtag/SoundsOfChange?src=hash&ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw">#SoundsOfChange</a>". ??<br><br>Watch now <a href="https://twitter.com/CBS?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw">@CBS</a> and <a href="https://twitter.com/paramountplus?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw">@paramountplus</a>! <a href="https://t.co/T0ihoTtqkY">pic.twitter.com/T0ihoTtqkY</a></p>— Recording Academy / GRAMMYs (@RecordingAcad) <a href="https://twitter.com/RecordingAcad/status/1372368415659286530?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw">March 18, 2021</a></blockquote> <script async src="https://platform.twitter.com/widgets.js" charset="utf-8"></script>

The specter of war was addressed with, well, "War," the Norman Whitfield tune we know from Edwin Starr's version. And after his piano-and-gospel version of his 2021 anti-Trump song "Weeping in the Promised Land"—crescendoing with a collective wail of "I can't breathe!"—John Fogerty rocked things up with Creedence Clearwater Revival's thrilling, outraged, oft-misunderstood classic "Fortunate Son."

Cutting to the essence of the other-ness that feeds racial division, CBS's Gayle King sat down with singer-actor Billy Porter to discuss the struggles of growing up gay and Black—and how music with a social conscience is returning to the forefront in 2021.

"I'm feeling once again the energy surrounding the power of protest music," Porter said. When asked about his choice to cover Patti LaBelle's "You Are My Friend" for the show, "I just wanted to choose something that was about chosen family," he added. "We talk often in this world about family values, but what happens when your family—your biological family—don't have the tools to understand how to love you?"

As Porter sang the empathetic ballad on a flower-festooned stage, images of people of all colors, identities and persuasions embracing—often draped in rainbow flags—flashed on the screen. "I want to talk to you a little bit about where I've been in the world!" he crowed midsong.

<blockquote class="twitter-tweet"><p lang="en" dir="ltr">Watch <a href="https://twitter.com/BradPaisley?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw">@bradpaisley</a> sing "Welcome To The Future" during "A <a href="https://twitter.com/hashtag/GRAMMYSalute?src=hash&ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw">#GRAMMYSalute</a> To The <a href="https://twitter.com/hashtag/SoundsOfChange?src=hash&ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw">#SoundsOfChange</a>," right now on <a href="https://twitter.com/CBS?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw">@CBS</a> / <a href="https://twitter.com/paramountplus?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw">@paramountplus</a>. ?</p>— Recording Academy / GRAMMYs (@RecordingAcad) <a href="https://twitter.com/RecordingAcad/status/1372379977799335937?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw">March 18, 2021</a></blockquote> <script async src="https://platform.twitter.com/widgets.js" charset="utf-8"></script>

"A GRAMMY Salute To The Sounds Of Change" also honored and elevated Latin voices. After a brief preamble from Common about the meaning and import of the neologism "Latinx," Gloria and Emilio Estefan discussed how Latin music is woven into the fabric of American social change. Their daughter Emily Estefan then performed "This Is What," a tribute to Sonia Sotomayor, the first Hispanic and Latina member of the Supreme Court.

<blockquote class="twitter-tweet"><p lang="en" dir="ltr">With her parents watching, <a href="https://twitter.com/GloriaEstefan?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw">@GloriaEstefan</a> and <a href="https://twitter.com/EmilioEstefanJr?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw">@EmilioEstefanJr</a>, <a href="https://twitter.com/Emily_Estefan?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw">@Emily_Estefan</a> performs "This Is What" ?<br><br>Watch "A <a href="https://twitter.com/hashtag/GRAMMYSalute?src=hash&ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw">#GRAMMYSalute</a> To The <a href="https://twitter.com/hashtag/SoundsOfChange?src=hash&ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw">#SoundsOfChange</a>" on <a href="https://twitter.com/CBS?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw">@CBS</a> / <a href="https://twitter.com/paramountplus?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw">@paramountplus</a>. ✨ <a href="https://t.co/kl7pWZzxzk">pic.twitter.com/kl7pWZzxzk</a></p>— Recording Academy / GRAMMYs (@RecordingAcad) <a href="https://twitter.com/RecordingAcad/status/1372377223320199168?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw">March 18, 2021</a></blockquote> <script async src="https://platform.twitter.com/widgets.js" charset="utf-8"></script>

Sotomayor was nominated in 2009 by then-President Barack Obama, and Brad Paisley touches on the legacies of our first Black president and first lady. From the floor of the Woolworth on 5th restaurant in Nashville, the country star performed his ascendant "Welcome to the Future," which he wrote in response to Obama's election. Paisley then strolled to the counter, explaining that the restaurant was a historic spot where John Lewis and his friends took a stand for racial justice in 1960.

<blockquote class="twitter-tweet"><p lang="en" dir="ltr">Right now <a href="https://twitter.com/YolandaAdams?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw">@YolandaAdams</a> delivers a performance of <a href="https://twitter.com/hashtag/MahaliaJackson?src=hash&ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw">#MahaliaJackson</a>'s "We Shall Overcome". ?? <br><br>Keep watching "A <a href="https://twitter.com/hashtag/GRAMMYSalute?src=hash&ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw">#GRAMMYSalute</a> To The <a href="https://twitter.com/hashtag/SoundsOfChange?src=hash&ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw">#SoundsOfChange</a>" on <a href="https://twitter.com/CBS?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw">@CBS</a> / <a href="https://twitter.com/paramountplus?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw">@paramountplus</a>. ? <a href="https://t.co/QUsOc9orRI">pic.twitter.com/QUsOc9orRI</a></p>— Recording Academy / GRAMMYs (@RecordingAcad) <a href="https://twitter.com/RecordingAcad/status/1372381502613417984?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw">March 18, 2021</a></blockquote> <script async src="https://platform.twitter.com/widgets.js" charset="utf-8"></script>

The special then homed in on "We Shall Overcome," a cornerstone of the civil rights movement. Yolanda Adams laid down a reverent monologue about the tune to the haunting strains of a gospel choir. But then, something unexpected happened. The lights flared up, and Adams upshifted several gears, launching into a raucous take on the soul-strengthening classic.

It was a joyful capper for a heartening night, conceived and broadcast for all the right reasons. But most importantly, almost every minute of "A GRAMMY Salute To The Sounds Of Change" was stuffed with music, which is usually the loam from where real change springs.

"A GRAMMY Salute To The Sounds Of Change" is available on-demand on Paramount+.

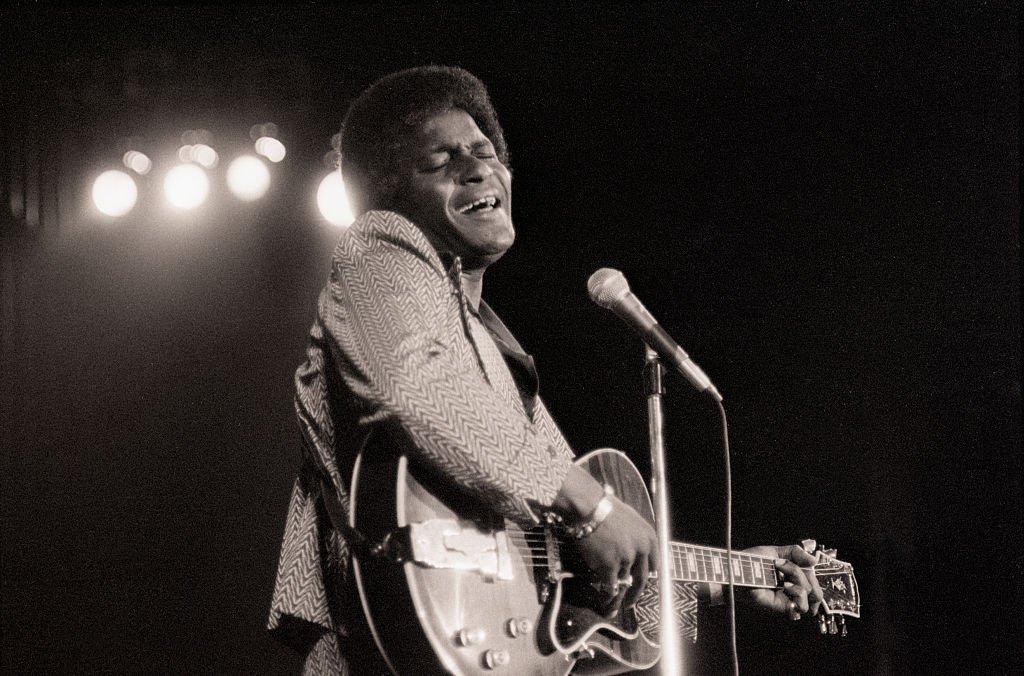

Charley Pride in 1975

Photo: Bettmann / Contributor

news

For Charley Pride, Black Country Music Was A Self-Evident Truth

The late icon may have stuck out like a sore thumb in Nashville, but given that country music is a rightfully Black art form, he was a participant, not an anomaly

Charley Pride was on the on-ramp to Nashville fame—then his audience discovered how he looked. In 1967, after two non-charting singles, his third, "Just Between You And Me," had pierced the Top 10 on the Hot Country Songs chart. Pride had guitar pioneer Chet Atkins, producer “Cowboy" Jack Clement and manager-agent Jack Johnson in his corner. In short, he was moving. But when Pride strolled into the spotlight at the Olympia Stadium in Detroit, clamorous applause curdled into an awkward silence.

Undoubtedly aware of the audience's reaction, Pride hesitated before laying into his first song. Instead, he leaned his arms on his acoustic guitar, as if to drag over a chair and say, "Let's rap for a moment."

"Ladies and gentlemen, I realize it's kind of unique, me coming out here on a country music show wearing this permanent tan," he quipped. "But my name's Charley Pride, and I am from Mississippi. My daddy was a farmer down there, and I sing country music. And I want to entertain you if you'll let me."

Was Pride unique in the country music world? Absolutely. To date, the Grand Ole Opry has welcomed 211 performers as members; Pride is one of only three Black members. (The others include DeFord Bailey, the harmonica trailblazer, and Darius Rucker, the singer of Hootie & The Blowfish.)

That said, was Pride an anomaly? An interloper? A novelty act? God, no. The three-time GRAMMY winner and Recording Academy Lifetime Achievement Award recipient was right where he belonged, alongside country music's giants. He stayed there until his death, caused by COVID-19 complications, this weekend (Dec. 12). He was 86.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//FxM4GDimobE' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

"Music is about breaking barriers. As one of the first Black superstars in country music, Charley Pride did just that," Harvey Mason jr., Chair & Interim President/CEO of the Recording Academy, said in a statement. "A three-time GRAMMY winner and 13-time nominee, the Recording Academy feels this loss deeply. During his nearly five-decade-long career, Pride inspired artists and paved the way for so many in the industry, which is why the Academy honored him with our Lifetime Achievement Award in 2017. He’ll be sorely missed, but we are grateful for the remarkable legacy he leaves behind."

If you trace country music's lineage, it's a straight line through Black American sounds, from the Civil War to Lil Nas X's genre-bending "Old Town Road," despite an apparent lack of visibility of Black artists in the genre.

"I think the history books, unfairly, will mostly note that Charley Pride was a great country singer who was African-American," radio host Bobby Bones said in the 2019 documentary, American Masters: Charlie Pride: I'm Just Me. "You can take off the African-American part."

Exhibit A of country music's Black origins lies in the banjo, which has so many roots in Africa that Béla Fleck once spent a whole multimedia project tracking them down. Flash-forward to the late-19th and early-20th centuries: Pride was keenly aware that Black folks formed the country's musical building blocks. "American music is made up of gospel, country and the blues. Those three," he explained in the documentary. "And I think each one borrowed from the other over the years that I've grown up and listened to the music."

Comb through Wikipedia, and you'll find numberless examples of this transracial interchange, from Jimmie Rodgers' and Louis Armstrong's "Blue Yodel No. 9" to Buck Owens' and Bettye Swann's long-unreleased collaborations. Since the 1920s, though, when labels segregated albums by "hillbilly records" and "race records" and effectively scrubbed Black fingerprints from country music, many people have associated the genre as a largely white sound. Country's historically whitewashed hegemony, which made Pride out to be less a natural participant than an interloper, still reflects this artificial wedge between the two races.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//z-ErGB5_Y7Q' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Any critical analysis of Pride's life and career will tell you he was country to the bone, regardless of his melanin content. Hard-luck story? Check: Pride was the fourth of 11 children born to sharecropper parents in Sledge, Miss. He ran from the punishing, unrelenting work of cotton-picking for the rest of his life. "It reminds me of what I don't ever want to go back to doing because it hurts my fingers and my back and my knees," Pride said during a televised performance before launching into Lead Belly's "Cotton Fields." Does his music check out? No doubt: Pride played straight-ahead, traditional country and western with a magnetic voice somewhere in George Jones' zip code.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//k_zvrVojgpw' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Pride was anything but oblivious to racism, but he once maintained that he never caught as much as a flippant remark. "It never did happen," he said in I'm Just Me. "I've never had one catcall, or iota of something like Jackie Robinson went through in my whole career, to this very moment. When that question is asked, I say, 'No, I haven't.' I get that 'I can't believe' look or 'You gotta be kidding' look or 'I don't believe you.'" As his mother, Tessie Pride, told him, according to the documentary, "Don't go around with a chip on your shoulder. There's good people everywhere. You've got a lot you're going to have to do, and you can't do it carrying a load of resentment with you."

Pride could have ignored that maternal advice and wielded his Blackness in a provocative or inflammatory way. Given the history of anti-Black violence, segregation and oppression in America, few would have blamed him. Instead, he chose to acknowledge his racial background good-naturedly and good-humoredly, and he never wavered from the idea that God put him on this Earth to be a country singer.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//HW2v76evSUM' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

No matter what the good old boys in Music City, U.S.A., might have thought, Pride was a Black artist in a rightfully Black art form. As such, the story of country music contained a blank page with his name on it. Zoom out and consider the whole timeline, and you'll find that Pride playing country music was like Chuck Berry architecting rock 'n' roll, Mary Lou Williams braiding jazz, gospel and swing, or Kendrick Lamar recoding the DNA of the rap game. No person would question their credentials in their genres, and no matter how outnumbered Pride was in a white-centric market, he belonged to the country music world just as much.

Back to Pride on stage at the Olympia Stadium, standing alone against stunned silence. He could have rightfully hectored the crowd as a bunch of bigoted hillbillies, but that wasn't Pride. Instead, he disarmed them with a joke. "Then, he started singing," Vanderbilt professor Alice Randall said in I'm Just Me. "The applause came back."

John Prine Was The Master Of Lyrical Economy