From left: David Corio/Redferns; Paul Natkin/Getty Images; Scott Gries/Getty Images; Richard E. Aaron/Redferns

feature

Songbook: A Comprehensive Guide To Tom Waits’ Evolution From L.A. Romantic To Subterranean Innovator

As Tom Waits’ series of Island Records releases from the ‘80s and ‘90s are being reissued, take an album-by-album trip through the legendary singer/songwriter’s significant body of work.

When Tom Waits warned on "Underground," the first song on his transformational 1983 album Swordfishtrombones, "there’s a rumblin’ groan down below," he very well could have been describing the artistic awakening that made him a legend.

Once an earnest yet good-humored singer/songwriter, Tom Waits is the rare artist in the past 50 years to successfully pull off something as radical as a complete artistic reinvention. A songwriter with a taste for the dark and grotesque as much as the theatrical, Waits has built up a catalog heavy on bizarre characters, morbid nursery rhymes, gruff junkyard blues and a uniquely unconventional take on rock music. And though it took some experimentation, trial and error and eventually getting married to arrive on the sound we hear today, he’s made a five-decade career of embracing sounds on the fringe and turning them into memorable melodies.

A Southern California native who got his start playing folk clubs in San Diego before relocating to Los Angeles in the 1970s, Tom Waits debuted as a relatively conventional singer/songwriter with a twinge of blues and jazz in his bones. And where his earliest records found him singing with more of a raspy croon, he adopted a vocal growl more spiritually akin to Louis Armstrong and Captain Beefheart.

Waits never quite fit in alongside peers such as Jackson Browne or James Taylor. His instincts often pushed himself somewhere a little dirtier and darker, favoring tales of vagabonds and outcasts told with an inebriated sentimentality and irreverent humor. Throughout his decades-long career, the two-time GRAMMY winner never let go of the emotional honesty in his songwriting.

Waits has joked that he makes two types of songs: grim reapers and grand weepers. The former became his staple sound in the 1980s after he married longtime creative partner Kathleen Brennan and began his decade-long tenure on Island Records, which still occasionally found him returning to the latter via less frequent but no less disarming ballads.

What once was a songbook reflective of the bars and familiar streets evolved into surreal dens of iniquity and theaters of the grotesque. Waits' knack for storytelling and character development only strengthened over the years, even as his songs took more oddball and ominous shape. Swordfishtrombones' "Sixteen Shells from a Thirty-Ought Six" follows a hunter following a crow into a Moby Dick-like epic; spoken word standout "What’s He Building In There?," from 1999’s Mule Variations, prompts the listener to ponder who’s really up to no good.

Though his record sales have been modest, Waits' songs have been covered by the likes of Rod Stewart and Eagles, and he’s collaborated with everyone from Bette Midler to Keith Richards. His songwriting and unique musical aesthetic have influenced records by Andrew Bird, Neko Case, Morphine and PJ Harvey.

As Waits’ acclaimed series of albums on Island Records from the ‘80s and ‘90s are being reissued in remastered form — some for the first time on vinyl in decades — GRAMMY.com revisits the legendary singer/songwriter’s significant body of work via each of his studio albums. Press play on the Spotify playlist below, or visit Apple Music, Pandora, and Amazon Music to enter Waits' sonic wonderland of '70s era ballads and his plethora of twisted narratives and experimental sounds.

The Barroom Balladeer

Though often treated to his own idiosyncratic filter, Waits’ early output in the ‘70s reflected the glamor and sleaze of his Los Angeles surroundings.

Closing Time (1973)

Making his debut at the height of the ‘70s singer/songwriter boom, Tom Waits revealed only slight glimpses of his myriad idiosyncrasies on 1973’s Closing Time. Heavily composed of ballads, the album’s sound is a result of a compromise between Waits’ own preference for more jazz-leaning material and producer Jerry Yester’s penchant for folk.

Despite, or perhaps because of, that creative tension, Closing Time has a unique character. A sense of wanderlust and escape within its 12 piano-based songs feels like a jazzier, West Coast counterpart to Bruce Springsteen. Waits imbues the call of the road with a sense of melancholy on gorgeous opener "Ol’ 55" and gives a hefty tug at the heartstrings on the aching "Martha." He kicks up the tempo on "Ice Cream Man." Closing Time is often at its best when it’s more quietly haunting, like on the bluesy "Virginia Avenue."

Though the album didn’t initially garner much critical or commercial attention, it’s since become regarded as one of the finest moments of Waits’ early recordings. It also quickly earned the respect and admiration of other artists, with various songs from Closing Time being covered by Bette Midler, Eagles and Tim Buckley.

The Heart of Saturday Night (1974)

After establishing himself with the romantic ballads of his debut album, Waits waded deeper into the waters of boho jazz and beat poetry in its follow-up, The Heart of Saturday Night.

Waits shares his perspective from the piano bench and the barstool, occasionally delving into a sing-speak delivery against upright bass and brushed-drum backing. Throughout, Waits serves up colorfully embellished imagery about nights on the town and getting soused on the moon. Though not as experimental or sophisticated as some of his later recordings, The Heart of Saturday Night nonetheless finds Waits in a more playful mood, more overtly showcasing his sense of humor and penchant for a particular kind of down-and-out protagonist. Fittingly, the album's title track was directly inspired by Jack Kerouac.

The Heart of Saturday Night is somewhat autobiographical in that it’s one of the few albums that repeatedly features references to his youth growing up in San Diego. Most famously on "San Diego Serenade," as well as in his narrative of driving through Oceanside in "Diamonds on My Windshield," and his name-drop of Napoleone’s Pizza House, the pizzeria in National City where he worked as a teenager, in "The Ghosts of Saturday Night."

Nighthawks at the Diner (1975)

As Tom Waits further established himself as a singer/songwriter more at home in the naugahyde and second-hand smoke of a seedy nightclub than a folk festival, he sought to replicate the atmosphere of a jazz club on his third album. It’s not a live album in a literal sense; Waits invited a small crowd into the Record Plant studio in Los Angeles on two nights in July of 1975, and though the venue is artifice, the crowd reactions are genuine.

More heavily rooted in jazz than Waits’ first two albums, Nighthawks at the Diner mostly follows a particular pattern: An "intro" track featuring some witty barfly banter, followed by an actual song. Introducing each song with a round of inebriated wordplay ("you’ve been standing on the corner of Fifth and Vermouth," "Well I order my veal cutlet, Christ, it just left the plate and walked down to the end of the counter…") is a bit of a gimmick, yet for all its loose, freewheeling feel, the album features some of his best early songs, including "Eggs and Sausage," "Warm Beer and Cold Women" and "Big Joe and Phantom 309."

Releasing a manufactured live album early on proved a canny gambit for Tom Waits and resulted in his highest charting album up to that date. And it’s easy to see why: Nighthawks showcased the raconteur persona that’d come to define much of Waits' work to come.

The Bluesy Bohemian

Embracing a grittier sound and a more character-driven approach to storytelling, Tom Waits entered a period of creative growth in the second half of the ‘70s that saw him balancing a darker tone with a wry sense of humor.

Small Change (1976)

On his second and third albums, a jazz influence and increasingly prominent humor saw Waits developing not just as a distinctive personality, but as a character. His raspy growl deepened onSmall Change, as Waits' barfly persona finds himself in increasingly seedier surroundings. This new area is best showcased through the amusingly unsexy striptease scat of "Pasties and a G-String" and the surreal and misty eyed "The Piano Has Been Drinking."

Small Change isn’t nearly as jokey as the previous year’s Nighthawks at the Diner, but Waits carries a persistent smirk as he rattles through a laundry list of hucksterish advertising slogans in the carnival-barker beat jazz of "Step Right Up": "It gets rid of unwanted facial hair, It gets rid of embarrassing age spots, It delivers the pizza." He even ramps up an element of danger in the noir poetry of "Small Change (Got Rained on With His Own .38)".

Still, the heartache and romance remains within the album’s best ballads, including the gorgeous opener "Tom Traubert’s Blues" and the imagined depiction of a lonely waitress in "Invitation to the Blues."

Foreign Affairs (1977)

Tom Waits’ fifth album Foreign Affairs unexpectedly became one of his most consequential releases.

A rare Waits album that opens with an instrumental ("Cinny’s Waltz"), Foreign Affairs finds him taking on more narrative driven songwriting, as in the lengthy noir tale of "Potter’s Field" and the nostalgic road-movie recollection of "Burma-Shave." It seems fitting that this is the moment where Hollywood began to crack a door open for Waits — these songs sound like they were made for the silver screen.

Indeed, album standout "I Never Talk to Strangers," a duet with Bette Midler, inspired Francis Ford Coppola’s 1981 film One From the Heart. Waits wrote and performed on its soundtrack, and would work with Coppola multiple times.

Blue Valentine (1978)

Parallels between Waits' music and his acting career crop up throughout , beginning with 1978’s Blue Valentine. Released the same year that he made his acting debut in Paradise Alley — cast as a piano player named Mumbles, an apt role to be sure — Blue Valentine opens with a big, cinematic number itself, Rodgers and Hammerstein’s "Somewhere," the famous ballad from West Side Story.

Blue Valentine also finds Waits in character development mode, increasingly populating his bluesy and bedraggled songs with widows and bounty hunters, night clerks and scarecrows wearing shades. It also features one of his most heartbreaking songs in "Christmas Card from a Hooker in Minneapolis," in which Waits’ first-person epistle comes from the voice of the title character who reaches out to an old friend in a hopeful and warm update on the changes she’s made for the better. And then he seamlessly, devastatingly pulls out the rug from underneath it all, as only a fabulist like Tom Waits can.

Heartattack and Vine (1980)

The transition from one decade to the next couldn’t have been starker for Tom Waits as he entered the 1980s. His final album for Asylum Records seemed to signal a sea change, with its leadoff track steeped in scuzzy, distorted guitar and gruff blues-rock rather than piano balladry, jazz and beat poetry.

Heartattack and Vine is in large part more of a proper rock record than any of Waits’ earlier albums, as he lends his husky growl to gritty songs such as "Downtown" and "In Shades." Still, it’s the most tender moments that comprise some of Heartattack and Vine’s most enduring songs, such as "On the Nickel" and, in particular, "Jersey Girl," covered four years later by the Garden State’s own Bruce Springsteen.

The Avant-Garde Auteur

Tom Waits underwent a significant transformation in the 1980s, mostly leaving behind the smoky jazz-club ballads of the ‘70s in favor of a more avant garde take on rock music, rife with an arsenal of unconventional instruments.

Swordfishtrombones (1983)

The most dramatic shift in Tom Waits’ career came with the release of 1983’s Swordfishtrombones, his first release for Island Records and the first album of what came to be the sound most often associated with Waits. It’s rougher, rawer, more experimental and offbeat. A great deal of the credit goes to Waits’ wife, Kathleen Brennan, who introduced him to artists like Captain Beefheart and who became his creative partner, co-writing many of his best-known songs.

Waits trades the piano and strings of his earlier material for arrangements better fit for junkyard jam sessions and New Orleans funerals. Though he’s delivered a long list of releases that have since usurped such a title, Swordfishtrombones certainly sounded like his weirdest album at the time. Very little of it sounded like a conventional pop song;it’s interwoven with spoken-word pieces both hilarious and unnerving ("Frank’s Wild Years," "Trouble’s Braids"), instrumentals ("Dave the Butcher," "Rainbirds"), boneyard bashers ("Underground," "16 Shells from a Thirty-Ought Six") and even a few tender ballads ("Johnsburg, Illinois," "Town With No Cheer").

Though arguably far less commercial than anything he’d released prior, Swordfishtrombones still cracked the bottom half of the album charts. It also received the attention of critics, who praised Waits’ bold new direction and unconventional stylistic choices.

Rain Dogs (1985)

For much of the 1970s, Tom Waits took inspiration from the seamier side of Los Angeles, with occasional sentimental nods to his youth further south along Interstate 5 in San Diego. With 1985’s Rain Dogs, however, he relocated to New York City to capture an even grimier and grittier album inspired by its outcasts and outlaws.

Recorded in what was then a rough part of Manhattan in 1984, Rain Dogs continues the stylistic experimentation of Swordfishtrombones with an unusual array of instruments for a rock album, including marimba, trombone and accordion, the latter of which opens the title track in dramatic fashion with an incredible solo.

Rain Dogs also began Waits’ long collaborative relationship with Marc Ribot, whose guitar playing helps craft the album's signature sound. Through his Cuban jazz-inspired playing on "Jockey Full of Bourbon" and the scratchy and dissonant solo on "Clap Hands." Yet the album also finds him in the company of Keith Richards, whose licks appear on the album’s most famous song, "Downtown Train," which became a hit for Rod Stewart when he covered it in 1991.

Rain Dogs features Waits’ first co-writing credit from Brennan, brought dded gravitas to the aching ballad "Hang Down Your Head." It’s one of a few moments that cuts through the carnivalesque atmosphere of the album (see the demented nursery rhyme "Cemetery Polka," the crime-scene poetry of "9th and Hennepin" and the litany of misfortunes in "Gun Street Girl"). IRain Dogs is Tom Waits perfecting his approach, completing a stylistic transformation with one of his greatest batches of songs.

Frank’s Wild Years (1987)

One of the highlights of Waits’ 1983 album Swordfishtrombones was a humorous spoken-word jazz interlude wrapped up in a David Lynch nightmare, titled "Frank’s Wild Years," in which the titular Frank settles down into a suburban lifestyle, only to set his house on fire and drive off with the flames reflecting in his rearview mirror. Those 115 seconds or so were enough for Waits and Brennan to spin the idea out into a stage play, with this album serving as its soundtrack. (Its original cast at Chicago’s Steppenwolf Theatre included Gary Sinise and Laurie Metcalf.)

Frank’s Wild Years likewise comprises songs performed in the play, though without the context of knowing its origins, it doesn’t so easily scan as a set of songs written for the stage. It continues the aesthetic vision that Waits pursued on his two previous Island Records albums, steeped in Weill-ian cabaret and mangled lounge-jazz renditions, like in the hammy Vegas version of "Straight to the Top." Waits continues to run wild stylistically, however, veering from junkyard blues-rock in opener "Hang On St. Christopher" to the tenderness of the lo-fi 78-style recording of closing ballad "Innocent When You Dream."

Fifteen years after its release, "Way Down in the Hole," was given a second life as the theme for the HBO drama "The Wire," each season featuring a different artist’s rendition of the song. Waits’ original scores the opening credits for season two.

Bone Machine (1992)

The title of Tom Waits’ tenth album fairly accurately sums up the sound of the record, which finds Waits incorporating heavier use of curious forms of percussion, many of them he played himself. Opening track "Earth Died Screaming" even resembles the sound of bones clanking against each other as Waits growls his way through an apocalyptic nightmare.

It’s fitting that Bone Machine coincided with Waits’ appearance as Renfield in Francis Ford Coppola’s Bram Stoker’s Dracula. A macabre sensibility and grotesque narratives permeate this record:Acts of violence become a form of entertainment in "In the Colosseum," and he retells an actual story of a grisly homicide in "Murder in the Red Barn." There’s levity too, like in the delusions of a fame-seeker in the rowdy "Goin’ Out West," which, along with half the songs on the album, was co-written by Brennan.

Eerie and macabre as Bone Machine is, it earned Waits his first GRAMMYAward, for Best Alternative Music Album in 1993. Likewise, the Ramones covered standout track "I Don’t Wanna Grow Up" three years later on their final album ¡Adios Amigos!; Waits repaid the favor in 2003 with a cover of the band’s "Return of Jackie and Judy."

The Storyteller’s Songbook

Deeper into the ‘90s and ‘00s, Waits became more active in writing music for the theatrical stage, albeit filtered through his own peculiar lens. He also closed out the ‘90s with his longest album, helping to usher in a late-career renaissance.

The Black Rider (1993)

The soundtrack to a theatrical production,The Black Rider closed Waits' tenure with Island Records with the soundtrack to a theatrical production. Though his music appeared in films by the likes of Jim Jarmusch and Francis Ford Coppola, and he entered the world of theater with Frank’s Wild Years, this was his released composed in collaboration with playwright Robert Wilson — they would work on three productions together — based on German folktale Der Freischütz. In fact, Waits affects his best German accent in the title track, in which he beckons, "Come on along with ze black rider, we’ll have a gay old time!"

Highlights "Flash Pan Hunter," "November" and "Just the Right Bullets" juxtapose distorted barks against ramshackle arrangements of plucked banjo, clarinet and singing saw. , The structure of the album — rife with interludes, instrumentals and reprises — sets it apart from any of his prior works, leaving room for the listener to fill in the visual blanks.

Mule Variations (1999)

The release of Mule Variations coincided with the launch of Anti- Records, an offshoot of L.A. punk label Epitaph that was more focused on legacy artists in a variety of genres. This also resulted in the unlikely instance of a song by Tom Waits appearing on one of Epitaph’s famed Punk-O-Rama compilations, which typically featured selections by the likes of skatepunk icons NOFX and Pennywise.

The longest studio album in Waits’ catalog, Mule Variations makes good on a six-year gap by being stacked with an eclectic selection of songs, most of them co-written with Brennan (who also co-produced the album). From the lo-fi beatbox bark that blows open the doors of leadoff track "Big In Japan," Waits essentially takes a tour through a disparate but cohesive set of songs that feels like a career summary, from tent-revival blues ("Eyeball Kid"), to devastating balladry ("Georgia Lee") and rapturous gospel ("Come On Up to the House").

A new generation of TikTok users received an introduction to this album via a meme featuring the album’s "What’s He Building In There?", an eerie spoken-word track from the perspective of a paranoid, busybody neighbor that became an unlikely viral sensation.

Blood Money & Alice (2002)

Another collaboration with playwright/director Robert Wilson, Blood Money and Alice were released on the same day in 2002. Co-written by Brennan, both are the soundtracks to two plays, the former based on an unfinished Georg Büchner play Woyzeck and the latter an adaptation of Alice in Wonderland.

Blood Money is darker and harsher in tone, kicking off with the satirically pessimistic "Misery is the River of the World," and featuring highlights such as the obituary mambo of "Everything Goes to Hell" and the charmingly tender "All the World Is Green."

Alice — whose songs had been circulated for years in bootlegs in rougher form — is more subdued and strange, its gorgeously lush and haunting opening ballad an opening into a head-spinning world of Lewis Carroll surrealism and disorientation. "Kommienezuspadt" soundtracks White Rabbit hijinks through German narration and Raymond Scott machinations, "We’re All Mad Here" lends a slightly darker shadow to an uneasy tea party, and "Poor Edward" diverts slightly from Carroll canon to visit the story of Edward Mordrake, a man born with a face on the back of his head.

The Catalog Continues…

Though Waits hasn’t been quite as prolific in the past two decades as he had been from the ‘70s through the late ‘90s, he continued to refine and evolve his strange and uncanny sound, while sharing a triple-album’s worth of rare material that offered a wide view of his evolution over the prior two decades.

Real Gone (2004)

Waits maintained his prolific streak with the lengthy Real Gone, which featured 16 songs and spans nearly 70 minutes — just a hair shorter than his longest, Mule Variations. It’s also the rare Tom Waits album to feature no piano or organ, its melodies primarily provided via noisier guitar from Harry Cody, Larry Taylor and longtime collaborator Marc Ribot, along with contributions from Primus bassist Les Claypool and Waits’ own son, Casey, who provides percussion and turntable scratches.

Real Gone is, at its wildest, the most abrasive record in Waits’ catalog, clanging and clapping and clattering through uproarious standouts such as the supernatural mambo of "Hoist That Rag," the CB-radio squawk of "Shake It" and creepy-crawly stomp "Don’t Go Into That Barn," one of his better scary stories to tell in the dark. He leaves a little room to ease back on dirges like the haunting "How’s It Gonna End" and the subtly gorgeous "Green Grass," but every corner of the album is populated by outsized characters and ominous visions that seem larger than ever.

Orphans: Brawlers, Bawlers and Bastards (2006)

A career as long and fruitful as that of Tom Waits is bound to leave some material on the cutting room floor, the likes of which is compiled on the triple-disc set Orphans. Composed of non-album material that stretches all the way back to the 1980s, it’s divided into three distinctive themes: Brawlers, a disc of rowdier rock ‘n’ roll and blues material; Bawlers, a set of ballads; and Bastards, made up of what doesn’t fit into the other two categories — essentially Waits’ most fringe, peculiar music.

In drawing the focus toward each distinctive type of songs, Waits lets listeners experience more intensive, discrete aspects of his music. It’s the "Bastards," however, that tap into the extremes of Waits’ unique talents, comprising strange and macabre storytelling, unintelligible barks, even a wildly distinctive take on "Heigh Ho," from Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.

Some of these songs had previously been released in some fashion — many of them appearing on movie soundtracks as well as collaborative efforts like Sparklehorse’s "Dog Door" — Orphans speaks to how productive he’s been over the past 40 years.

Bad As Me (2011)

Tom Waits’ final album (so far) hit shelves 12 years ago, the aftermath of which opened up his longest stretch without any new music since he began releasing records. Yet Bad As Me only offers the suggestion that Waits still has plenty of energy and inspiration left in the tank, as the album — released when he was 61 years old — comprises some of the hardest rocking material he’s ever committed to tape. It’s an album heavy on rowdy rock ‘n’ roll guitar, including that of Keith Richards, who had also previously lent his guitar playing to 1985’s Rain Dogs, as well as longtime collaborator Marc Ribot and Los Lobos’ David Hidalgo. Waits mostly adheres to concise, charged-up barnburners such as "Let’s Get Lost," "Chicago" and the more politically charged anti-war song "Hell Broke Luce." Though when Waits does ease off the throttle on songs like the eerie "Talking at the Same Time," the results are often spectacular.

If Tom Waits were to simply leave this as the end of his recorded legacy, it’d be a satisfying closing statement, though the closing ballad "New Year’s Eve" — ending on a brief round of "Auld Lang Syne" — would suggest new beginnings ahead of him. As it turns out, Bad As Me isn’t intended to be his last; earlier this year he confirmed that, for the first time in over a decade, he’s been working on writing new songs.

Songbook: A Guide To Wilco’s Discography, From Alt-Country To Boundary-Shattering Experiments

feature

Songbook: How Bruce Springsteen's Portraits Of America Became Sounds Of Hope During Confusing Times

In this edition of Songbook, GRAMMY.com explores how Bruce Springsteen's empathy for his working-class characters evolved alongside his own commercial success. The Boss is the subject of a new exhibit at the GRAMMY Museum, Bruce Springsteen Live!

If you knew nothing else about him there’s still a good chance you’d recognize Bruce Springsteen by the name "The Boss." The nickname predates his entire career as a recording artist, going back to his days as a teenage bandleader at the Jersey Shore. In a bit of amusing irony, it’s also a name that stands in complete contrast to his 50 year canon of songs from the perspective of working-class folks. "I hate being called the boss," Springsteen admitted in a 1999 biography. "I hate bosses."

In "The Wish," a 1987 studio outtake eventually released on *Tracks* in 1998, Springsteen’s narrator traces his adult prosperity as The Boss back to a single childhood Christmas when his mother bought him a "brand-new Japanese guitar." The lyrics echo Springsteen’s real-life story of his own first electric guitar — a Japanese-made Kent, that he purchased for $70 in 1964 with the help of a loan his mother had taken out. Fifty-seven Christmases later, in December 2021, Springsteen sold his fifty-year catalog of songs for a record-setting $550 million dollars.

Over the course of those 50 years, Springsteen has won 20 GRAMMY Awards, two Golden Globes, an Academy Award for Best Original Song, and a Tony Award for his one-man show "Springsteen on Broadway." Though still one EMMY Award short of a full EGOT, he’s nonetheless made do with honors like the Presidential Medal of Freedom awarded to him in 2016 by President [Barack Obama](https://www.grammy.com/artists/barack-obama/4975) (with whom he would later host a podcast and write a *New York Times* bestselling book) and a planet — 23990 Springsteen — named in his honor.

From his inauspicious start to his initial commercial peak in the 1980s, and through a career resurgence in the early 2000s, one of the Boss’ most remarkable achievements is that his songs have never seemed to lose their blue-collar everyman perspective. If anything, Springsteen's early climb to success found him advocating more fiercely and empathetically for the American working class. Over the decades and 20 studio albums, he established an unmatched pedigree for literary power and modern everyman myth-making, — powers that would eventually put him back in the spotlight at a time when America desperately needed those types of stories.

In this edition of Songbook — and ahead of the launch of *[Bruce Springsteen Live!](https://grammymuseum.org/event/brucelive/)* at the GRAMMY Museum — GRAMMY.com explores how The Boss’s empathy for his working-class characters evolved alongside his own commercial success in the 1970s, and how that reputation gave way to his comeback in the 2000s.

"A town full of losers": 1972 - 1975

Bruce Springsteen was only 23 years old when he signed to Columbia Records in 1972, but had already been thoroughly fawned over by local live music critics and industry types who were hailing the young songwriter as something like "the next [Bob Dylan](https://www.grammy.com/artists/bob-dylan/3014)."

Although his 1973 debut *Greetings from Asbury Park, NJ* and its September followup *The Wild, The Innocent & The E Street Shuffle* both underperformed commercially compared to that effusive praise, the young songwriter was beginning to carve out his thematic niche, expanding granular portraits of Jersey Shore life into ambitious outsized literary dramas. The sophomore record closes on a 10-minute-long rock opera called "New York City Serenade" set in a brutal and desperate vision of the Big City that poses a constant threat to the song’s impoverished fictional protagonists: "It’s midnight in Manhattan, this is no time to get cute," Springsteen whispers. "So walk tall / Or baby, don’t walk at all."

After the commercial disappointment of the first two records, released less than a year apart, Columbia offered a massive hail mary budget to Springsteen and the newly-minted E Street Band for their third record, which they recorded over a grueling and obsessive 14 month period. When it was finally released in 1975, Born To Run became a breakthrough record for the band almost in spite of Columbia’s similarly aggressive marketing campaign. The album, which peaked at No. 3 on the Billboard 200, showed steady growth in its first few weeks on the backs of a successful word-of-mouth radio campaign, itself based on a leaked early mix of the title track.

The real-life underdog story of Born To Run bubbles up under every beat and every word, with an inherent drama that builds gentle tracks into dense and theatrical finales. Overeager characters like the narrator of "Born To Run" talk themselves through feverish and impassioned cases for escaping the "death trap" of small town life and an existence doomed to "sweat[ing] it out on the streets / Of a runaway American dream."

The long-winded narrator of "Thunder Road" puts the stakes more bluntly: "It’s a town full of losers / And I’m pulling out of here to win." The abstraction between those characters and their authors — a young band mounting a last-ditch effort at breaking out of the local bar band circuit into a tangible future in music — allows *Born To Run* to point outwards to a much broader feeling of American restlessness: the particularly youthful and overzealous belief that our potential in life is limited only by our force of will.

"I ain’t nothin’ but tired": 1978-1984

As *Born To Run* lifted the band into steady commercial success, Springsteen's portraits of working class life were growing increasingly disillusioned and fatalistic. Throughout their 1978 followup *Darkness on the Edge of Town*, Springsteen recharacterizes working class restlessness as a self-destructive impulse that drives the album’s characters into crime and compulsive thrill in a meager attempt at escaping from the endless grind of their working lives. In 1980 they released their biggest hit yet, "[Hungry Heart](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=boJhWtw-6Gg)" — a misleadingly upbeat lead single from *The River* in which a narrator tries to use restlessness as an excuse for suddenly abandoning his wife and kids.

The title track of *The River* mines an even more devastatingly ordinary sense of realism in telling the story of a teenage couple whose relationship is eroded over the years by the whim of the volatile economic conditions around them. Like before, Springsteen dangles a symbol of escape — a nearby river where the couple used to swim in their honeymooning days — but after years of growing alienation it starts to become a symbol of a life they were never allowed to have, and a relationship that was doomed from the beginning. "Is a dream a lie if it don’t come true?" Springsteen sings quietly in the climax, through clenched teeth. "Or is it something worse / That sends. me down to the river / Though I know the river is dry?"

Nebraska, released in 1982, was the first album Springsteen had ever recorded without the E Street Band. Assembled from a set of cassette demos Springsteen had recorded alone at home, the album’s stark and lonely acoustic landscapes matched an even bleaker assessment of poverty and the American Dream. Its characters — outcasts, outlaws, and children who seem doomed to become one or the other — speak through Springsteen with a soft and inarticulate reservedness about a world of economic chaos and violence that was both fundamental and inescapable.

The album begins almost identically to *Born To Run:* the narrator pulls up to a house where a girl stands out front, and eventually they drive off together in an attempt to escape their prescribed lot in life. But where "Thunder Road" had found personal urgency in a vague sense of autobiography, "Nebraska" is a true crime story narrated from the perspective of real-life spree killer Charles Starkweather, a 19-year-old garbage collector who killed 11 people across Wyoming and Nebraska with his girlfriend in 1957 after his economic anxiety gave way to an epiphany that "dead people are all on the same level."

Springsteen’s retelling withers the triumphant climax of "Thunder Road" into a resigned and uncertain declaration of inevitability: "They wanted to know why I did what I did," Springsteen murmurs. "Well, sir, I guess there’s just a meanness in this world."

Born In The USA, Springsteen’s colorful and energetic 1984 reunion with the E Street Band, would become not only Springsteen’s best selling record, but one of the best selling records of all time. Culled largely from the same writing sessions as Nebraska, its fist-pumping maximalism only barely obscures the lyrics’ continued descent into economic fatalism.

Its widely-misinterpreted, largely ironic title track is really a seething indictment of the United States’ treatment of returning war veterans; even the bouncy pseudo-nursery rhyme chorus of "Working on the Highway" openly bears its total resignation ("Working on the highway, laying down the blacktop / Working on the highway, all day long I don’t stop"). "[Dancing In The Dark](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nCFTL4IO6t4)," which won Springsteen his first GRAMMY in 1985, spins existential defeatism into something between a sad boy pickup line and a statement of solidarity: "I ain’t nothing but tired… Man I win’t getting nowhere / I’m just living in a dump like this," its narrator complains at first. "I’ll shake this world off my shoulders," he decides later. "Come on, baby, this laugh’s on me."

The album’s most subdued offering, "My Hometown," sheds the gentlest and most personal light on Springsteen’s hardened relationship to the conditions of the American working class as its narrator softly tangles nostalgic memories with an unflinching look at his hometown’s brutal history of racial tension and economic turmoil. When the town’s textile mill shuts down, putting a huge number of residents out of work, he finally decides to pack up his family and move away but implores his son to take one last look at where he comes from.

The second verse alludes to a real incident of racist violence that occurred in Springsteen’s own hometown of Freehold, New Jersey in the 1960s. Ironically, in 1986, two years after the song was released, Freehold closed its main manufacturing plant, a 3M factory, leaving hundreds of local laborers out of work. The Boss, at the height of his fame, returned home to perform at a benefit rally for the union workers being laid off, donating $20,000 himself.

"Let me be your soul driver": 1987 - 1995

Over the previous 14 years, as Springsteen crawled out of Freehold and into success and stardom, the conditions for the American working class had grown steadily worse. His increasing urgency in portraying blue collar desolation during that period shows an innate understanding of that new development, in spite of his own escape. By the end of *Born In The U.S.A.,* Springsteen had arrived at a complex and difficult truth: You can’t change where you come from, and the lucky few who manage to escape their economic circumstances will always inherently be leaving a whole "town full of losers" — many of them family — behind.

By the early 90’s Springsteen was living in Los Angeles with his family, and had unclenched his fists a little on the three solo albums (Tunnel of Love, Human Touch, Lucky Town) that followed Born In The U.S.A. In 1995, on the heels of his first Greatest Hits collection, Springsteen released The Ghost of Tom Joad — a spiritual sequel to Nebraska that applied its sense of stark isolation and themes of a broken American dream to stories that, in several cases, highlighted the experiences of undocumented immigrants.

The album won that year’s GRAMMY for Best Contemporary Folk Album, and proved just another dimension in the Boss’ legacy as an empathetic and unrelenting champion of the extraordinary bravery of ordinary folks persevering in thankless lives of hard work. Not long after, Springsteen decided to move back to New Jersey to raise his kids only a short drive away from where he grew up.

"I am the nothing man": 2002-2014

It would be seven years until Springsteen released his next album, *The Rising,* his first collaboration with the E Street Band in 18 years. Inspired by the September 11th attacks and at least one Asbury Park resident’s personal plea to Springsteen that "we need you now," *The Rising* intentionally finds a broader and more hopeful streak in its stories of ordinary people’s capacity for perseverance.

Dense with simple and earnest affirmations ("we’re going to find a way" / "it’s going to be okay" / "I’m going to believe") that somehow manage never to feel naïve *or* condescending, Springsteen and the E Street Band begin to take a more deferential perspective. That view would continue through the aughts, as the band continued to look loss and destruction in the eye but reshift focus onto the immense bravery of their characters in the face of chaos and confusion. Though the band’s bleaker songs had certainly never lacked empathy, the determination to wear it more proudly on their sleeves in *The Rising* marked the beginning of a commercial and creative renaissance — one which found Springsteen more comfortably inhabiting a role as a spokesperson for the ordinary people of an increasingly turbulent America.

During the 2004 Presidential election, Springsteen finally abandoned the pretense of separating his career and his partisan politics. He toured in support of Democratic nominee John Kerry; his 2005 solo album *Devils and Dust* empathizes, partly, with the disorienting experiences of soldiers fighting in the Iraq War; the next year, he used a record of Pete Seeger covers (*We Shall Overcome: The Seeger Sessions)* to make his most opaque and comprehensive declaration of his populist political beliefs.

2007’s Magic, a meditation on the erosion of personal freedoms in the Bush era, uses imagery of apocalyptic premonitions and magic tricks to tell stories about the inherent humanity of ignoring warning signs in an effort to believe someone who claims to have your best interests in mind. The complexity of that project — to characterize the era by attempting to empathize with, rather than denounce, the Americans who voted to re-elect Bush — feels perfectly Springsteenian in an era where political art was rapidly becoming the partisan battleground we continue to see today.

"We’ll meet at the house of a thousand guitars": 2019-present

During the Obama era, Springsteen and the E Street Band released three albums that returned to familiar stories of working class perseverance, with an overall attitude of building back: *Working On A Dream* in 2009*, Wrecking Ball* in 2012, and *High Hopes* in 2014. Then after five years (his longest gap between albums since *The Rising)* he released an inspired and imaginative new highlight, *Western Stars* — a record written and arranged in the style of the orchestral country pop of Springsteen’s youth.

This earnestness and more personal sense of nostalgia carried over into 2020’s Letters To You, an intimate and personal record inspired by the loss of longtime E Street Stalwarts Clarence Clemons and Danny Federici. In September 2022, Springsteen announced that his next record, Only The Strong Survive, would be a collection of cover songs from the classic songbook of his youth.

For any other artist of his stature and tenure, these nostalgic indulgences would probably indicate a sort of phoning-in — but for Springsteen they feel like a surprisingly immediate start to a new chapter. At worst, they’re a well-earned self-indulgence after countless albums of selfless advocacy and careful listening outside his own experiences; at best, they’re a reminder, after all that time, of his own deep and tightly-held ties back to the pantheon of characters in his songs.

Either way, the path ahead is imminent proof of a career built on an organic ebb and flow of inspiration, imploring us to trust Springsteen in his pursuit and discovery of new forms of urgency and realism in his storytelling.

It wouldn’t be wild to argue that he’s earned that trust in his listeners. He is, after all, The Boss.

Songbook: A Guide To Every Album By Guided By Voices' Current Lineup — So Far

Photos (L-R): Kevin Winter; Jim Smeal/Ron Galella Collection via Getty Images; Jewel Samad/AFP via Getty Images; David Crotty/Patrick McMullan via Getty Images

feature

Songbook: How Mariah Carey Became The Songbird Supreme, From Her Unmistakable Range To Genre-Melding Prowess

On the 25th anniversary of Mariah Carey's career-redefining 'Butterfly,' GRAMMY.com digs into every album and song that made her the unofficial Queen of Christmas and the pop queen of her generation.

Mariah Carey's personal favorite title might be "Queen of Christmas," but she has plenty more to her name: Five-time GRAMMY winner, Songwriters Hall of Fame inductee, record-breaking chart-topper, and bonafide superstar — among many more.

The five-octave vocalist almost instantly became a household name upon her debut with 1990's "Vision of Love," which marked her first No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100. Carey has since landed an astounding 19 atop the chart (only one behind the record-holding Beatles), and sold more than 200 million albums worldwide.

But Carey's long list of achievements didn't come without hard work. The Long Island native spread herself thin between waitressing, beauty school and singing backup for Brenda K. Starr, all the while penning her own music with hopes of making it as an artist herself. Then, with the help of Starr, Carey's demo tape ended up in the hands of music mogul Tommy Mottola and the rest, as they say, is history.

After starting out her illustrious career with five multi-platinum albums in a row — including her smash holiday album Merry Christmas — Carey decided that a new musical direction was long overdue. And with that, on Sept. 16, 1997, Carey released her self-proclaimed magnum opus: Butterfly.

With contributions from Diddy, Q-Tip, Bone Thugs-n-Harmony, and Dru Hill, Butterfly leaned heavily toward R&B and hip-hop compared to Carey's previous works. While a couple of tracks allude to Carey and Mottola's deteriorating marriage, at its core, Butterfly is a coming-of-age story through the lens of a young woman who is finding her voice, becoming more independent, and enjoying her newfound liberation.

In fact, Carey loves Butterfly so much, she's releasing eight bonus tracks on Sept. 16 to commemorate the anniversary. GRAMMY.com is also getting in on the celebration, revisiting the hits, trailblazing remixes, holiday tunes, and musical risks that made the Songbird Supreme one of the most imitated vocalists and influential artists — and why her catalog remains a blueprint.

Listen to GRAMMY.com's official Songbook: An Essential Guide To Mariah Carey playlist on Spotify, Apple Music, Amazon Music, and Pandora. Playlist powered by GRAMMY U.

The Impressive Start

Swiftly amassing a string of No. 1 and top 10 hits, including "Vision of Love," "Can't Let Go," and "Dreamlover," Mariah Carey was on the fast track to becoming one of the top-selling artists of the '90s before the age of 25.

Released in 1990, Carey's eponymous debut studio album spawned an impressive four Hot 100 chart-toppers: "Vision of Love," "Love Takes Time," "Someday," and "I Don't Wanna Cry." Carey's five-octave range and signature whistle register made the then 20-year-old an instant success. But her producing and songwriting chops — unbeknownst to many at the time — set her apart from fellow divas Whitney Houston and Celine Dion.

To capitalize off the success of her debut album, Carey churned out her second studio effort, Emotions, a few months after earning her first two GRAMMY Awards in 1991. (She took home Best New Artist and Best Pop Vocal Performance, Female for "Vision Of Love.") For Emotions, Carey enlisted C+C Music Factory's Robert Clivillés and the late David Cole for the LP's uptempo tunes, including "Make It Happen," as well as the lesser-known tracks "You're So Cold" and "To Be Around You."

The title track became Carey's fifth No. 1 single. With this feat, she's the only artist to have her first five singles soar to the top of the Hot 100.

In 1993, following two multi-platinum albums and a flawless MTV Unplugged performance, Carey welcomed the biggest blockbuster success of her three-decade career: Music Box. Sonically, the LP remains the most pop-leaning of Carey's discography, with the exception of gospel-infused "Anytime You Need a Friend," the album's final single. Perhaps most prominently, Music Box birthed "Hero," one of Carey's signature songs that even the most casual fans can probably recite word for word.

The R&B Period

While Butterfly is cited as Carey's transition from mostly pop music to R&B and hip-hop, 1995's Daydream was her first venture in those worlds thanks to collaborations with Boyz II Men ("One Sweet Day") and Jermaine Dupri ("Always Be My Baby"). "Underneath the Stars" pays homage to Minnie Ripperton, while "Long Ago" echoes Zapp & Roger's "More Bounce to the Ounce" bassline.

Daydream is also notable for kicking off Carey's long-standing tradition of autobiographical album closers. "She smiles through a thousand tears," Carey laments in the second verse of "Looking In," her most personal song at the time. The song served as an important shift for Carey, as it detailed her feelings of unhappiness and "adolescent fears" — despite having a highly successful music career — and showed a deeper side of the singer's songwriting abilities.

Ahead of Butterfly's 25th anniversary, Carey wrote on Instagram that it's her "favorite and probably most personal album." Butterfly's lead single "Honey" and final single "My All" earned Carey two more No. 1s, but the true highlights are within the deep cuts and other singles. Despite receiving little promotion, "The Roof (Back in Time)" and "Breakdown" quickly emerged as fan favorites.

Along with a more mature sound, Carey presented a sexier image, as evidenced in the James Bond-themed music video for "Honey" that takes the album's empowerment theme a step further. She did that lyrically as well with the Missy Elliott co-written track "Babydoll," which contains some of Carey's most sensual lyrics.

As the singer noted herself, Butterfly is also deeply personal. Carey recently shared that the album represented a "pivotal moment" in her life following her separation from Mottola, whom she divorced in 1998. She reportedly once stated that she penned the title track "wishing that that's what [Tommy Mottola] would say to me," and "Close My Eyes" intertwines the stories of Carey's tumultuous childhood with her strained marriage. What's more, Butterfly's closing track, "Outside," chronicles her struggles growing up as a biracial person.

Carey continued her foray into more urban musical styles on 1999's Rainbow. She joined forces with Jay-Z for the first time on lead single "Heartbreaker," which also received a high-energy remix with Elliott and Da Brat that featured an interpolation of Snoop Dogg's "Ain't No Fun (If the Homies Can't Have None)" — further displaying her hip-hop sensibility.

Rainbow, of course, closed with a diaristic song — the gushing "Thank God I Found You," inspired by Carey's then-relationship with Latin star Luis Miguel — but she also sprinkled super-personal tales throughout the album. Ballads like "Can't Take That Away (Mariah's Theme)" and "Petals" offered fans an even deeper glimpse into Carey's personal life.

The (Semi) Forgotten Years

Carey ushered in a new decade by making her big-screen debut in the 2001 movie Glitter. The accompanying soundtrack paid tribute to the '80s, including the Cameo-sampling "Loverboy" and covers of Cherelle's "I Didn't Mean to Turn You On" and Indeep's "Last Night a DJ Saved My Life."

At the time, Glitter marked her lowest first-week sales, despite showing artistic growth. Carey eventually got #JusticeForGlitter, though, as the 12-track LP is hailed as a gem among Carey's most loyal fans — thanks to classic, yet overlooked ballads like "Never Too Far" and "Reflections (Care Enough)." (A #JusticeForGlitter campaign even sparked on social media in 2018, helping the album top the iTunes album chart 17 years after its release.)

In addition to Glitter's rather disappointing release, Carey was dealing with her own personal struggles: In July 2001, the singer was hospitalized for exhaustion, and in July 2002, she lost her father to cancer. She chronicled those hardships in 2002's Charmbracelet. "And if you keep falling down, don't you dare give in," she sings on opener "Through the Rain."

That same resilience and vulnerability can be heard in "My Saving Grace" and "Sunflowers for Alfred Roy," the latter of which is named after Carey's father. Elsewhere, Carey flexes her ability to excel in any genre, experimenting with jazz ("Subtle Invitation") and hard rock (a cover of Def Leppard's "Bringin' On the Heartbreak").

The Comeback

After two back-to-back underperforming albums with Glitter and Charmbracelet, it became easy for critics to write off Carey — that is, until the spring of 2005, when The Emancipation of Mimi arrived.

Following a moderate hit in lead single "It's Like That," second single "We Belong Together" proved that Mariah Carey the Chart Queen was back. Not only did the ballad spend 14 consecutive weeks at the No. 1 spot, but it was later crowned the "Song of the Decade" by Billboard.

But Carey's reign didn't end there. Follow-up singles "Don't Forget About Us" and "Shake It Off" skyrocketed to No. 1 and No. 2, respectively. The album also earned her three more GRAMMYs at the 2006 GRAMMY Awards: Best Contemporary R&B Album, as well as Best R&B Song and Best Female R&B Vocal Performance for "We Belong Together." (She earned 10 nominations total in 2006 and 2007.)

The success continued with 2008's E=MC² and 2009's Memoirs of an Imperfect Angel, which spawned another No. 1 ("Touch My Body" from E=MC²) and a top 10 hit ("Obsessed" from Memoirs). The albums contain some of Carey's most carefree material ("I'm That Chick"), as well as vivid storytelling ("Betcha Gon' Know (The Prologue)") and a taste of her sense of humor ("Up Out My Face").

In the 2010s, as music streaming continued to disrupt the industry, Carey once again proved her staying power, earning two top 5 albums — 2014's Me. I Am Mariah… The Elusive Chanteuse and 2018's Caution — and a top 20 hit with "#Beautiful," featuring then-rising R&B star Miguel.

The Remixes And Rarities

Carey is so dedicated to the art of the remix that she put out a double-disc project, The Remixes, in 2003. But she displayed her remix mastery nearly 10 years before that release, with the Bad Boy version of the Daydream hit "Fantasy" in 1995. When the late ODB growls, "Me and Mariah go back like babies with pacifiers" over a thumping Tom Tom Club-sampling bassline, Carey showed there were no boundaries to her music.

Over the decades, Carey has also teamed up with legendary DJs Shep Pettibone and David Morales for club versions of some of her biggest hits, including 1990's "Someday" and 1993's "Dreamlover." When it comes to her best hip-hop reimaginings, standouts include "Thank God I Found You" (Make It Last Remix), "Always Be My Baby" (Mr. Dupri Mix), and "I Still Believe/Pure Imagination" (Damizza Remix), the latter of which features a genius Willy Wonka interpolation and is a true testament to Carey's artistry.

As for B-sides, longtime fans treasure Music Box's "Do You Think of Me" and "Everything Fades Away" and "Slipping Away" from the Daydream sessions. In 2020, they were treated to The Rarities, a double-disc collection consisting of more B-sides and unreleased material collected throughout the decades, including a heartfelt cover of Irene Cara's "Out Here on My Own" and the original mix of "Loverboy," both recorded during the Glitter era.

The Christmas Magic

Fresh off the success of her first headlining tour, Carey was at her commercial peak when she tried her hand at Christmas music in the second half of 1994.

As expected, the now-iconic Merry Christmas is packed with festive classics like "Silent Night," "Christmas (Baby Please Come Home)," and "Santa Claus Is Comin' to Town." But it's the original "All I Want For Christmas Is You" that emerged as a new holiday standard. And that holds true even more than 25 years after its release: In December 2021, the song became the first to top the Hot 100 four chart years in a row — 2019, 2020, 2021 and 2022 (it held the top spot on the Jan. 1-dated chart).

Carey released Merry Christmas II You, an aptly titled sequel to Merry Christmas, in 2010. The album includes underrated singles "When Christmas Comes" (which was re-released as a duet with John Legend in 2011) and "Oh Santa!," which she performed alongside Ariana Grande and Jennifer Hudson during her star-studded 2020 Christmas special on Apple TV+.

The timeless success of "All I Want For Christmas Is You" earned Carey the unofficial title of "Queen of Christmas," but her extensive catalog and artistic versatility prove she's an icon outside of her holiday throne. Mariah Carey melded genres, influenced a generation of vocalists, and became the first artist with No. 1 singles across four decades — solidifying a legacy as the true Songbird Supreme.

How Many GRAMMYs Has Britney Spears Won? 10 Questions About The "Hold Me Closer" Singer Answered

Photos, from left: Ray Tamarra/Getty Images; Kevin Winter/Getty Images for NARAS; Lev Radin/Pacific Press/LightRocket via Getty Images; Alberto Tamargo/Getty Images

feature

Songbook: Celebrating Daddy Yankee's Legendary Three-Decade Reggaeton Reign

At the start of his farewell tour, GRAMMY.com examines the solo hits and collaborations that have made Daddy Yankee a living legend — and why countless of rising reggaeton artists are following in his footsteps.

Presented by GRAMMY.com, Songbook is an editorial series and hub for music discovery that dives into a legendary artist's discography and art in whole — from songs to albums to music films and videos and beyond. In this edition, GRAMMY.com pays tribute to reggaeton legend Daddy Yankee, examining his biggest hits and most memorable collaborations.

Daddy Yankee goes by many names: The Big Boss. El Jefe. El Cangri. The King. While many of them are self-proclaimed, it’s undeniable that the artist is a reggaeton icon. In his nearly three-decade-long career, Yankee (real name Ramón Luis Ayala Rodríguez) has reigned tall with hardly any visible competition (with all due respect to Don Omar), and his journey to the top is the stuff of legends.

In fact, the 46-year-old reggaetonero is the most successful person to emerge from the underground in the mid-'90s. He became el género's biggest export during its first international explosion in the aughts and, in the decades that followed, D.Y. has enjoyed a highly prolific career. As the genre currently enjoys massive mainstream popularity the world over, Daddy Yankee has also gained the respect and admiration of the majority of reggaeton’s new class.

Unbeknownst to many, Yankee coined the word "reggaeton" 1994 on DJ Playero’s seminal 1994 mixtape Playero 36 (DJ Nelson would popularize the word reggaeton the next year). His underground debut No Mercy (1995) laid the foundation for the future of reggaeton, fusing old-school hip-hop and turntablism against his signature dancehall-esque, quick-witted lilt. A decade later, Daddy Yankee fueled the reggaeton explosion with "Gasolina," and the rest is history.

Six Latin GRAMMY wins and four GRAMMY nominations later, the Big Boss remains a global force to be reckoned with. Following D.Y.'s recent retirement announcement, GRAMMY.com pays homage to his prolific and highly influential body. From Barrio Fino to "Despacito" and Legendaddy, we examine the solo hits and collaborations that have made the Puerto Rican artist a living legend — and why countless of reggaeton newcomers are following in his footsteps.

Listen to GRAMMY.com's official Daddy Yankee playlist on Spotify, Apple Music, Amazon Music, and Pandora.

The Global Hitmaker

The 2000s

Armed with a rapid-fire flow backed by a revving, EDM-driven thump, the former baseball player scored his first musical home run with "Gasolina" in 2004. Produced by Luny Tunes, the song became an instant gargantuan hit that unleashed reggaeton well beyond his island home.

In the Americas, Yankee became known as the face of a burgeoning scene and the incendiary song became the gateway to the genre for those outside of the Caribbean diaspora. The album cover of Barrio Fino — a candid black-and-white shot of Daddy Yankee looking off camera, donning a New York Yankees cap — inspiring legions of followers to sport Yankees hats.

In addition to expanding reggaeton’s international reach, the album is widely considered foundational for many reggaeton artists that followed. Daddy Yankee’s linguistic dexterity and influence on the genre was recognized at the 2005 Latin GRAMMYs, where "Gasolina" became the first reggaeton song to be nominated for the coveted Record of the Year; Barrio Fino earned him his first Latin GRAMMY for Best Urban Album Music.

Nearly two decades later, Barrio Fino’s countless hits — like the party-starting "Lo Que Pasó, Pasó," about an old fling, and "Tu Prínicpe" — continue to ignite dance floors at block parties and bourgeois resorts alike. In 2005, Daddy Yankee followed up with a live album and four new songs, including "Rompe," a fire-in-the-belly banger for serious perreo enthusiasts. His popularity accelerated well into the aughts, and Daddy Yankee was added to Time's list of 100 influential people in 2006.

The 2010s

The Boricua superstar journeyed to further sonic territory with 2010's Mundial, which employed equal parts braggadocio and trap experimentalism as heard on "El Mejor de Todos Los Tiempos" and "El Más Duro." Early signs of the then-new Latin trap seeped through, thanks to producers Musicólogo & Menes, while the Yankee also embraced beloved Puerto Rican tropical rhythms (hear the merengue on "La Despedida" and "Rumba y Candela").

Prestige arrived a couple of years later with more memorable bangers at the intersection between EDM, reggaeton, and electropop. In 2012, the rapper told a news outlet in Miami that Prestige is his "best and most complete album" yet. The charts and viral streams confirmed it: flashy, swaggering numbers like "Limbo" and "Lovumba" both peaked at No. 1 on the Billboard’s U.S. Latin charts; and the former song currently boasts a staggering 1.2 billion views on YouTube.

A new cohort of música urbana superstars that grew up on old school reggaeton — led by the likes of J Balvin, Ozuna, and, later, Sech and Karol G — gave the genre a more sophisticated makeover in the mid-2010s. Many of urbano’s rising stars cite Yankee as an inspiration, while their changes to the genre were also inspired by improved technology that refined production.

Meanwhile, new reggaeton fans began to explore the roots of the genre. While genre O.G.s such as Don Omar experienced a back-catalog boost, many slowed their new music release momentum — not Daddy Yankee. To popular perception, this made the D.Y. the default genre originator, with hardly any visible competition from peers.

During the later part of the decade, Daddy Yankee released a slew of singles and buzz-worthy collabs. As an unrivaled reggaeton icon, Yankee dropped "Shaky Shaky" and "Dura" to further virality. By the time of the reggaeton-pop of "Con Calma" (featuring Snow) and the tropical-soaked "Que Tire Pa Lante" — which samples vocals by the new hype generation including Bad Bunny, Natti Natasha, Anuel AA, and Darell, as well as genre pioneers like Wisin and Lennox — Daddy Yankee was unstoppable.

The Powerhouse Collaborator

When "Despacito" arrived in 2017, the reggaeton movement spread like wildfire. Daddy Yankee’s artistry and decades of street cred paid off in a huge way when he joined former rock balladeer Luis Fonsi for the now-omnipresent smash hit. Beyond his existing fame, the track instantly transformed D.Y. into a full-fledged Latin pop phenomenon. The song itself took on a new life of its own: "Desapcito" currently clocks in at a staggering 7.92 billion views, making it the second most watched video in YouTube history. Today, reggaeton and Latin pop are used interchangeably, and popular Latin pop playlists are loaded with reggaeton songs.

Perhaps one of Daddy Yankee's most memorable collaborations is "Oye Mi Canto" by N.O.R.E., also featuring Nina Sky, Gem Star and Big Mato. Entering the Billboard Hot 100 at No. 12 in 2006, this song helped catapult reggaeton to mainstream success. "Oye" also put the Latino/a and Black Latino/a presence on the map at a time when MTV largely aired music videos by white and African American artists.

Yankee's feature on "Machete" by Héctor El Father was another early banger that resonated throughout the underground. Released the same year that "Gasolina" dropped, the song channeled a similar bombastic energy and made maximalist reggaeton sound defiant.

The New Class

Reggaeton’s new cohort further helped elevate Daddy Yankee’s star to newer heights. In 2020, Panamanian sensation Sech invited an all-star cast — including Farruko, J Balvin, Yankee and superstar Rosalía — to sing in the remix of his hit song "Relación." "Daddy Yankee is the Big Boss, the best of all time," said Sech. "He’s not about just arriving and making a hit, he’s about maintaining, and if we talk about maintaining, he has the record."

As he continued to make huge strides within the ever-growing reggaeton empire, Daddy Yankee then stepped into Latin drill. In 2021, Yankee joined forces with Brooklyn drill pioneer Bobby Shmurda and J Balvin for a remix of trap rapper Eladio Carrión’s viral dissonant drill song "Tata." The song sees the D.Y. diving into darker territory while maintaining his bad boy image.

At the same time, Yankee was shedding that image: A few years earlier, he joined Janet Jackon for a more gleeful pop duet in New York City, and helped break then-teen reggaeton upstart Lunay on the remix of "Soltera," joined by Bad Bunny.

By combining sounds and styles from different generations, reggaeton is cementing its everlasting star power. This is exemplified in "Mayor Que Usted," a recent hit by Natti Natasha, Wisin & Yandel, and Daddy Yankee, which sees three artists of different stylistic leanings bring forward a potent reggaeton recipe. In the month and a half since its posting, the YouTube video already racked up 14.5 million streams.

LEGENDADDY

When considering his biggest hits and collaborations, it’s undeniable that El Jefe has made epic strides. As he plans his exit in full galore, Yankee leaves us with a riveting record for the reggaeton-pop cannon that encapsulates his dynamic and linguistic prowess. There are plenty of moments in LEGENDADDY (his seventh and final studio album, released in March) where D.Y.'s creative brilliance shines through, but in contemporary Latin pop fashion, he invites plenty of others to share the spotlight, while making his claim as the G.O.A.T.

In "Agua" starring Rauw Alejandro and fabled guitarist Nile Rodgers, the three artists summon a revamped pop-funk for perreo under a disco ball. Bad Bunny’s hit-making streak continues on the exhilarating club track "X Última Vez," and El Alfa brings forward his frenetic Dominican dembow dazzle on "Bombón," alongside unlikely guest Lil Jon. Our main man re-returns to the native tropical rhythms of Puerto Rico on "Rumbatón," all in all accumulating to a welcoming, farewell homage that captures Daddy Yankee’s enduring legacy.

From coining the genre to continually rewriting the música urbana playbook for over a quarter-century, and amassing 20.4 billion total YouTube views, there’s no denying that the Yankee has been helping transcend reggaeton’s cultural boundaries. As reggaeton enjoys plenty of global acclaim, this legendary daddy has every right to boast his bravado.

Photos (L-R): Paul Natkin/WireImage, Gary Miller/Getty Images, Chris Walter/WireImage, Johnny Franklin/andmorebears/Getty Images

feature

Songbook: A Guide To Willie Nelson's Voluminous Discography, From Outlaw Country To Jazzy Material & Beyond

Prodigious songwriter, interpreter and national treasure Willie Nelson has released dozens or hundreds of albums, depending on who you ask. Still, a few key entryways and rabbit holes can help you get a handle on this foundational country figure.

Presented by GRAMMY.com, Songbook is an editorial series and hub for music discovery that dives into a legendary artist's discography and art in whole — from songs to albums to music films and videos and beyond.

Cue up almost any Willie Nelson performance from the last 10 years, and you'll find something intriguing. Many other country greats are tight and precise onstage; Nelson is decidedly not.

While his Family band easily catches a groove on well-worn classics like "Family Bible," "Crazy" and "Funny How Time Slips Away," our permanently bandana-ed and pigtailed protagonist is attuned to deeper and stranger rhythmic dimensions. A Willie Nelson show is a particular kind of miasma — at times, it coheres; at times, it hovers almost beatlessly.

Sometimes, Nelson’s famously jazz-inflected syncopation threatens to swing him off the road — he'll strike his famously battered and weathered classical guitar, Trigger, at a moment that seems jarringly off the beat. His light and flinty voice has developed distinguished cracks and fissures with age. But if you're disappointed by his relative lack of polish, you're not just missing the point — you're missing the beauty.

First, nobody has ever picked up a guitar and sang a song like Nelson. The gods only made one of him, and the most fabulously expensive guitar on the market could never sound like Trigger. Second, the soul of country music is impactful storytelling and direct emotional transference, and nobody wields those twin abilities like Nelson, both as a songwriter and interpreter.

Indeed, without him as its cockeyed embodiment and one of its foundational figures, the world of country music would be unrecognizable — period.

Despite a few minor off-ramps during his almost seven-decade career, Nelson has built an astonishing body of work not via overhauling or reinvention, but becoming more himself every year. With every release, he digs deeper into his time-tested toolbox and aesthetic — often to heartening, comforting, and wizening results.

You don't approach the recently released A Beautiful Time, Nelson's fourth album in two years, for left turns; you do so because you want to know what the Beatles' "With a Little Help From My Friends" and Leonard Cohen's "Tower of Song" mean to him — as well as the state of his songwriting.

While the resin-caked hayseed vibe Nelson has embraced since the '70s may be a far cry from his crop-topped beginnings, you can drop the needle on any decade and hear an essentially unchanged artist and person. Whether he's channeling George Gershwin and crooning Broadway tunes, or running from the IRS on record — or even making reggae-inspired music, as on 1995's Countryman — Willie is Willie is Willie.

That said, the 10-time GRAMMY winner and 53-time nominee has either dozens or hundreds of albums, depending on how you count them. Where does one possibly begin? Given that he doesn't really have specific, delineated eras, it's more helpful to cherry pick the most essential albums, decade by decade, while still noting relatively minor entries of interest.

Let's go places we've never been, and see things we may never see again — in this edition of Songbook.

Listen to GRAMMY.com’s Songbook: An Essential Guide To Willie Nelson playlist on Spotify, Apple Music, Amazon Music and Pandora.

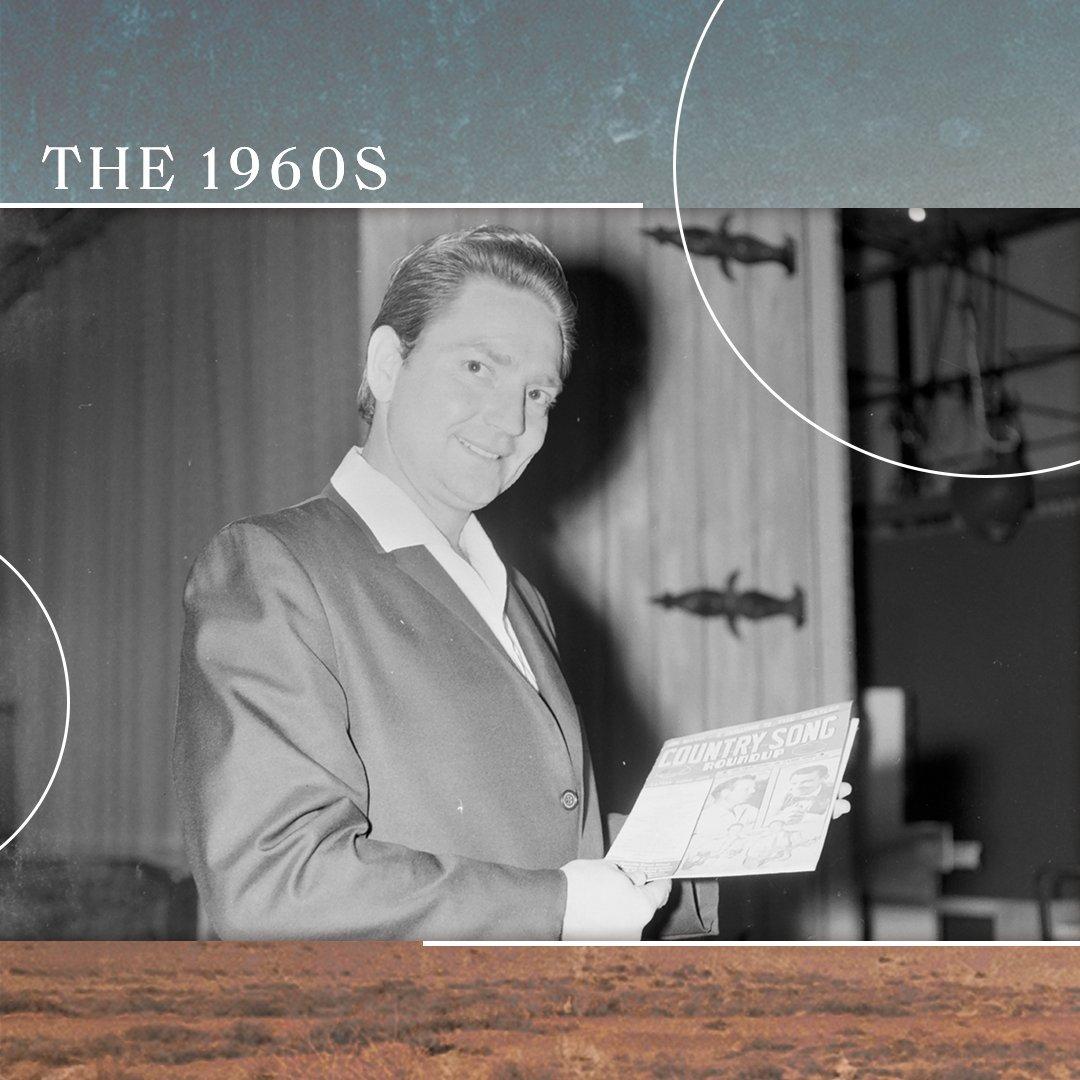

The 1960s

Willie Nelson backstage at "Arizona Hayride" TV show in November, 1964, in Phoenix, Arizona | Photo: Johnny Franklin/andmorebears/Getty Images

While Nelson made his first recordings in the mid-1950s, his discography began in earnest in 1962, with his debut album …And Then I Wrote.

…And Then I Wrote is absolutely worth hearing for its decadent production, introduction of Nelson's Django Reinhardt-inspired nylon-string picking, and key early compositions like "Funny How Time Slips Away" and "Crazy."

The baby-faced country crooner on the cover was in for the adventure of a lifetime. Listen to …And Then I Wrote, consider how Nelson's voice is pretty much the same 60 years on — albeit weathered by age and weed smoke — and you'll realize he essentially came out fully formed.

Do you dig the songs on …And Then I Wrote, but don’t like the semi-excessive reverb and instrumentation typical of Nashville back then? Head for 1965's Country Willie: His Own Songs for alternate versions of tracks like "Funny How Time Slips Away," "Mr. Record Man," and cuts from his second album, 1963's Here's Willie Nelson. But all in all, seek out 1973's The Best of Willie Nelson for a handy sampler platter from his first decade on record.

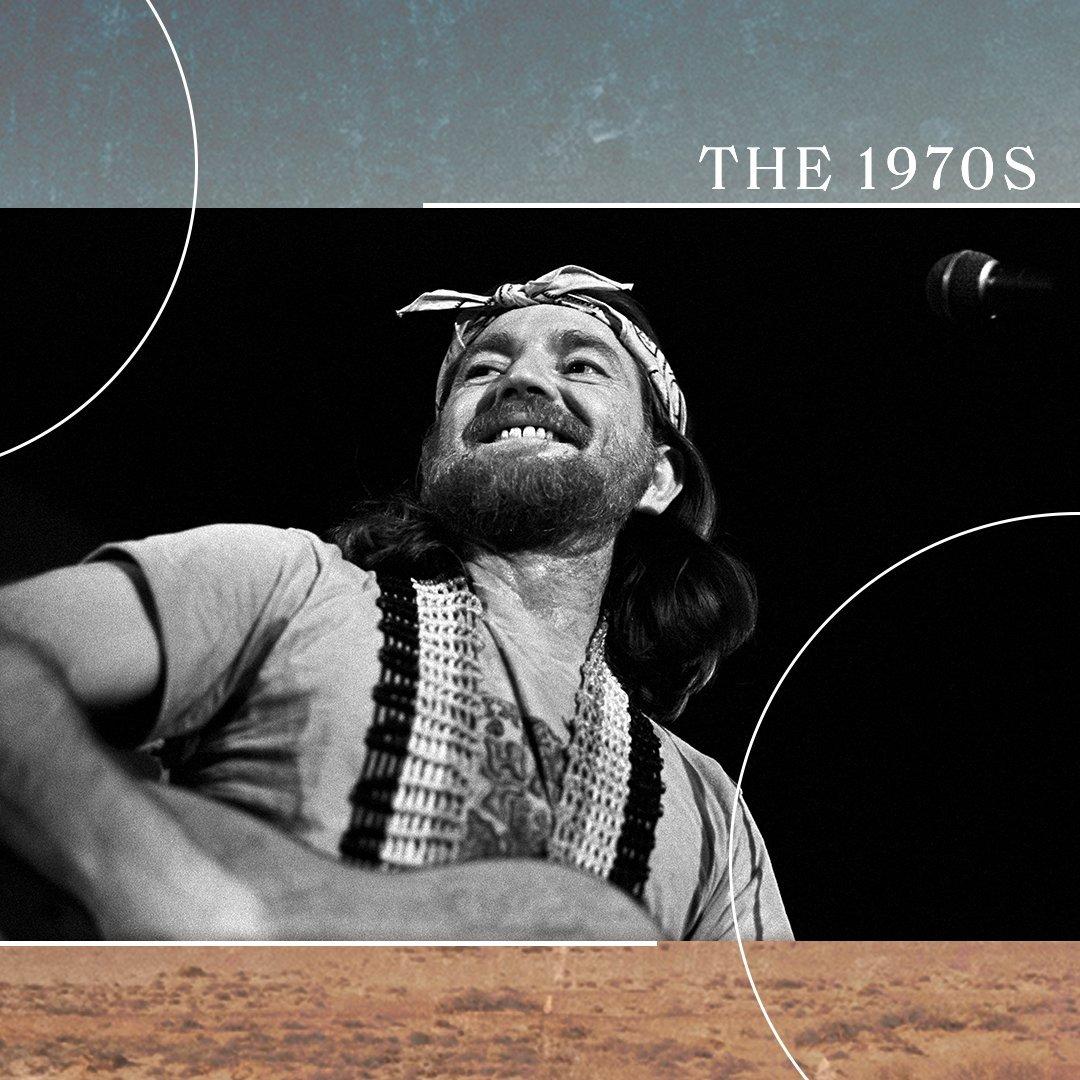

The 1970s

*Willie Nelson performs at the Great Southeast Music Hall on October 27, 1975 in Atlanta, Georgia | Photo: Tom Hill/Getty Images*

Forged and rebirthed by a ranch fire and divorce — not to mention professional bumps in the road — Nelson entered the 1970s with his first masterpiece: 1971's Yesterday's Wine, which contains classics like "Family Bible" and the title track.

Begin your trawling through Nelson's '70s with that record, then follow up with his 1973 breakthrough, Shotgun Willie, whose sound, attitude and songs helped forge the "outlaw country" subgenre. 1974's slightly less discussed Phases and Stages is a heady exploration of a marriage’s unraveling.

Then drop the needle on 1975's Red Headed Stranger, which further cemented Nelson's reputation as an outlaw-country mainstay and contained his immortal version of Fred Rose's "Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain." (Talk about making a shopworn song your own!)

If you want a more raucous Nelson offering from this decade, seek out 1976's The Troublemaker, a rough-and-tumble collection of traditional songs.

1977's To Lefty From Willie, a tribute to country singer Lefty Frizzell, is Nelson's first album-length tip of the hat to another artist — he'd later do the same for Ray Price and George Gershwin. And 1978's Waylon and Willie is worth engaging with simply to hear two titans appear on the same record.

The other 1970s entry you must hear is Stardust, which veers away from Nelson's outlaw-country image in favor of jazzy renditions of traditional pop songs, like "Unchained Melody," "All of Me," "Moonlight in Vermont," and — most famously — "Georgia on My Mind."

Given there has never been a jazzier country artist than Nelson, Stardust is a pivot point in his discography by concept alone — one that shows the true depths of his artistry. Seek it out for that reason, and stay for the luminous music.

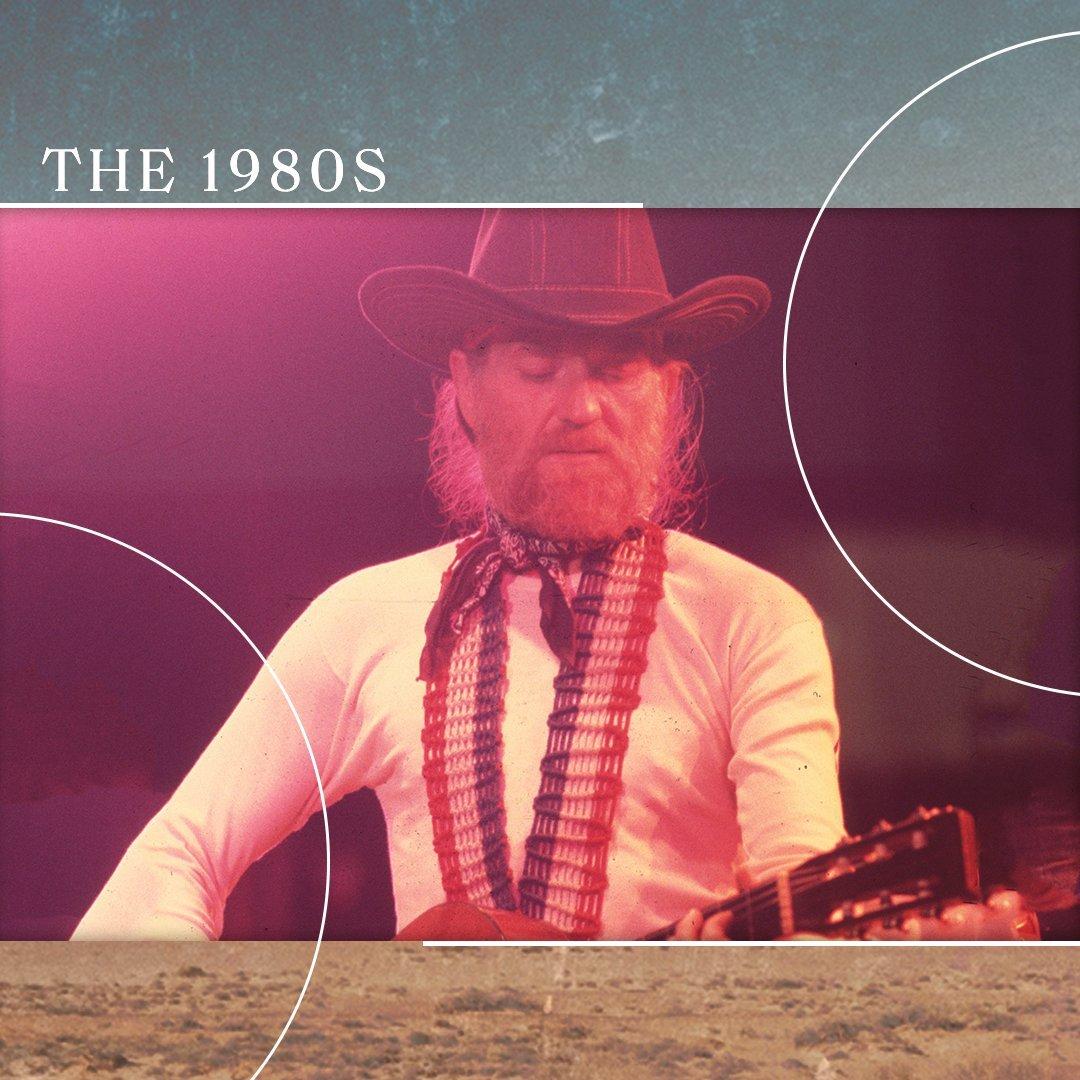

The 1980s

*Willie Nelson performs in 1980 | Photo: Chris Walter/WireImage*

Nelson kicked off the '80s with San Antonio Rose, a collaborative album with Ray Price that illustrated the profound bond between two foundational country figures. Also released in 1980, Family Bible was a duet album with Nelson's sister, pianist Bobbie, who passed away in 2022.

A successor of sorts to 1979's covers album Sings Kristofferson, Music From Songwriter was a duet between the pair. It also soundtracked the titular, well-recieved 1984 film, which starred both men.

The one drop-dead essential Nelson album of the decade, though, is 1983's Pancho & Lefty, his inspired team-up with fellow outlaw-countryman Merle Haggard.

The album featured unforgettable tunes like the Townes Van Zandt-penned title track — a narrative about a wanderer and Mexican "bandit boy" — as well as Haggard's "Reasons to Quit" and Jesse Ashlock's "Still Water Runs the Deepest." It also spawned multiple sequels, from 1987's Seashores of Old Mexico to 2015's Django & Jimmie.

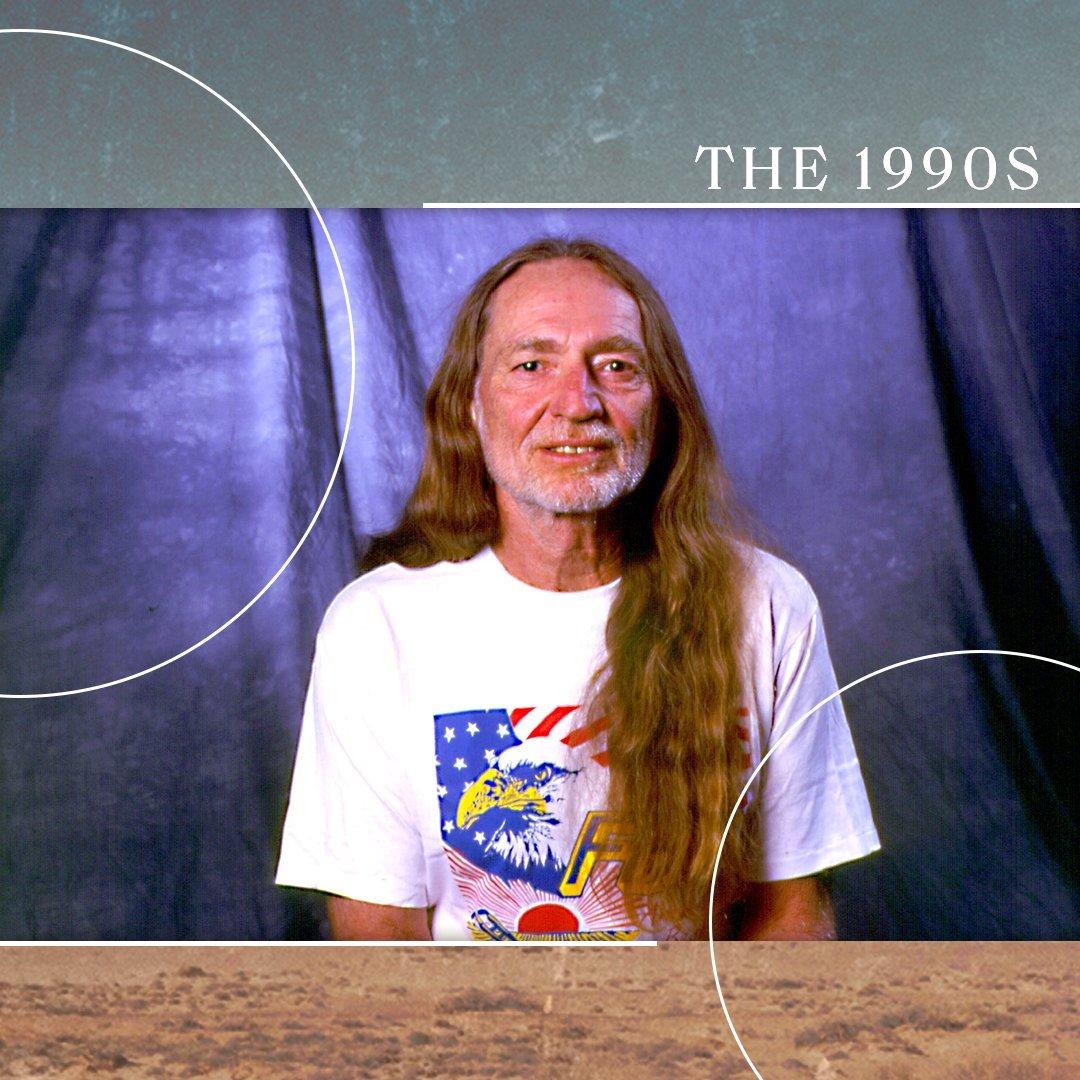

The 1990s

*Willie Nelson in New Orleans, Louisiana, in 1994 | Photo: Paul Natkin/WireImage*

Nelson had a beyond rocky start to the decade: in 1990, the Internal Revenue Service seized most of his assets, claiming he owed a whopping $16 million. Long story short, he recorded Who'll Buy My Memories: The IRS Tapes to pay off part of the debt.

Although the album was well-received, it's safe to say it exists more of a reminder of this bizarre yarn than a standalone album worth cherishing. (Thank goodness Trigger survived the property seizure — Nelson's daughter, Lana, shipped it to him in Hawaii.)

A far more essential '90s Nelson listen is the haunting, stripped-down, Spanish-influenced Spirit, a quintessential "real heads only" album.

Featuring fiddler Johnny Gimble of Bob Wills and His Texas Playboys, Spirit consists solely of crepuscular, yearning originals, like "Your Memory Won't Die in My Grave," "Too Sick to Pray" and "I Guess I've Come to Live Here in Your Eyes."

Also of interest from this decade in Nelson's discography: Teatro, which Daniel Lanois recorded in an old movie theater in Oxnard, California and features vocal contributions from the estimable Emmylou Harris.

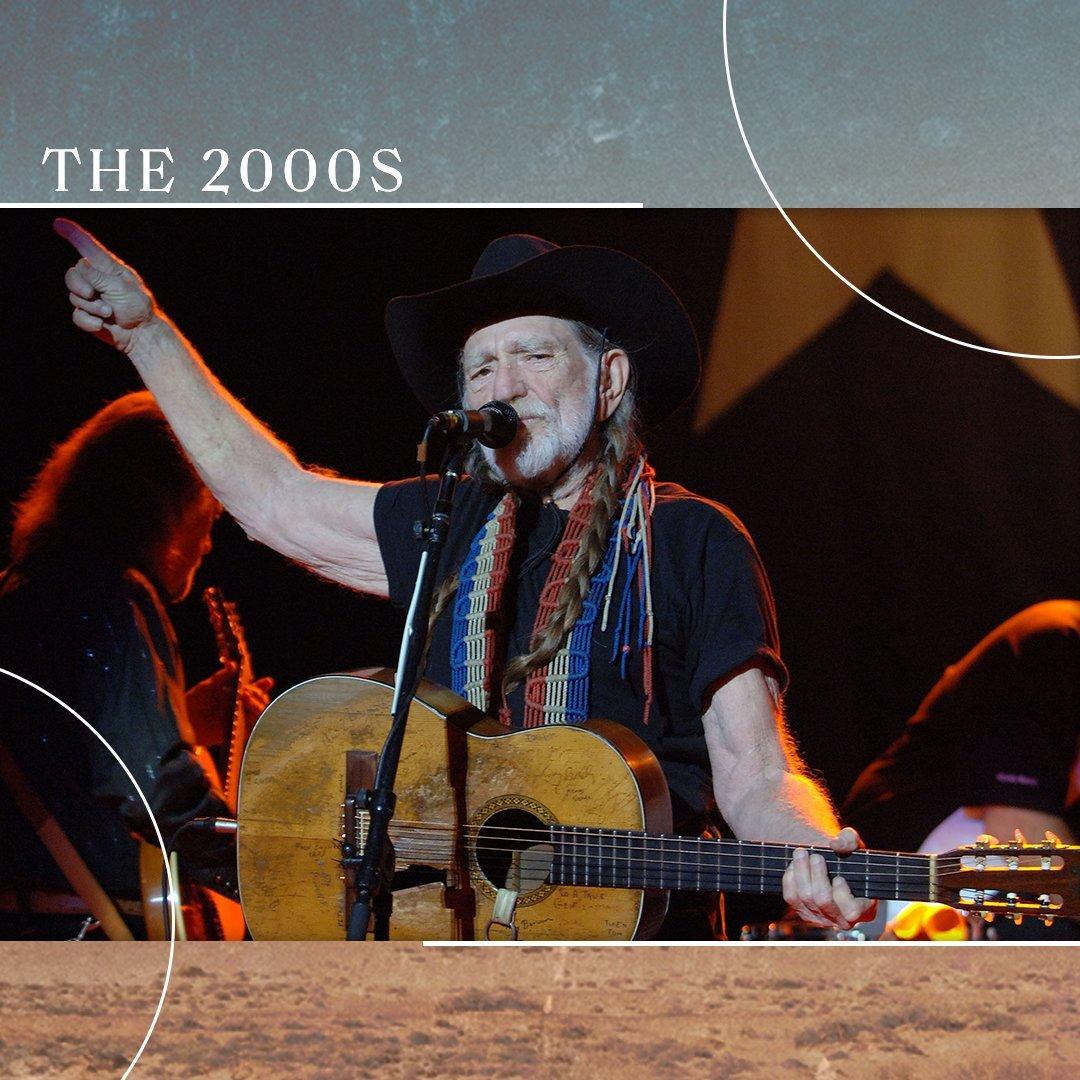

The 2000s

*Willie Nelson performs at The Mizner Park Ampitheatre in Boca Raton, Florida, in 2006 | Photo: Larry Marano/Getty Images*

In the young millennium, Nelson hit the road even harder than he did in the '90s, and collaborated with artists as divergent as Toby Keith ("Beer for My Horses"), Toots and the Maytals ("She is Still Moving to Me," "I'm a Worried Man") and Wynton Marsalis (2008's Two Men With the Blues).

The 2000s are also important in Nelson's development as they marked the start of his partnership with the two-time GRAMMY-winning producer Buddy Cannon. Their inaugural project was 2008's Moment of Forever, and Cannon produces or co-produces Nelson's yearly (or, in some cases, bi-yearly) albums to this day.

Other notable selections from this decade include 2006's Songbird, with Ryan Adams and the Cardinals, and 2007's western-swing excursion Last of the Breed, featuring the triple threat of Nelson, Haggard and Price.

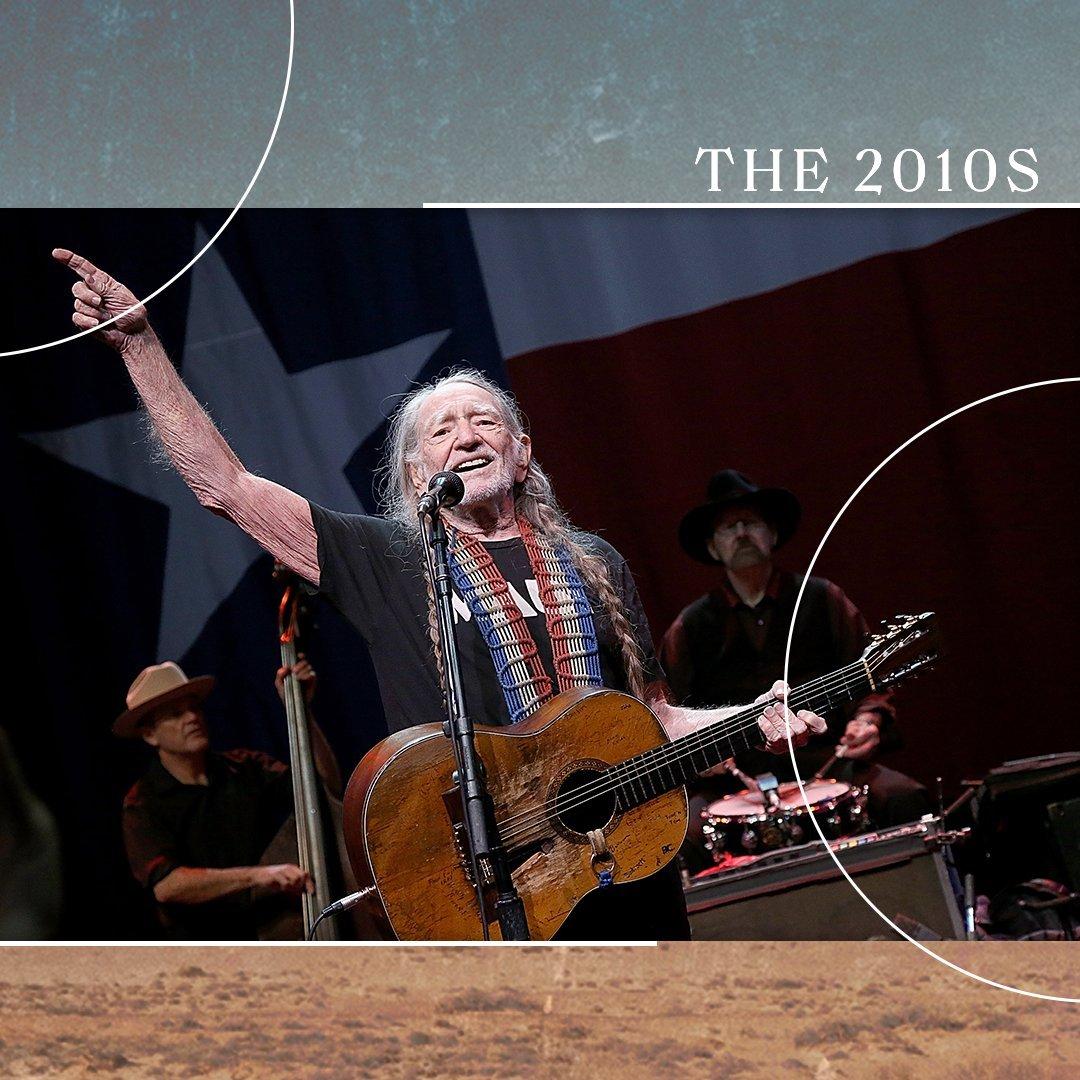

The 2010s

*Willie Nelson performs on New Year's Eve at ACL Live in 2014 in Austin, Texas | Photo: Gary Miller/Getty Images*

Nelson was consistent and prolific throughout the 2010s. If you're a fan or just curious, you can conceivably drop into almost any album — from 2012's Heroes to 2014's Band of Brothers to 2018's Last Man Standing — and walk away smiling.

That said, a few stand out from the pack. Django and Jimmie, which marks Nelson and Haggard's sixth and final collaborative album, is by turns touching ("Somewhere Between") and uproarious (the irresistible stoner boogie "It's All Going to Pot").

What's more, Django and Jimmie is a glorious penultimate dispatch from the very missed Haggard, who died in 2016. Nelson touchingly paid tribute to his fallen friend on "He Won't Ever Be Gone," from 2017's excellent God's Problem Child.

Finish off your exploration of 2010s Nelson with 2018's My Way, a tribute to Frank Sinatra, and 2020's spare-yet-satisfying Ride Me Back Home.

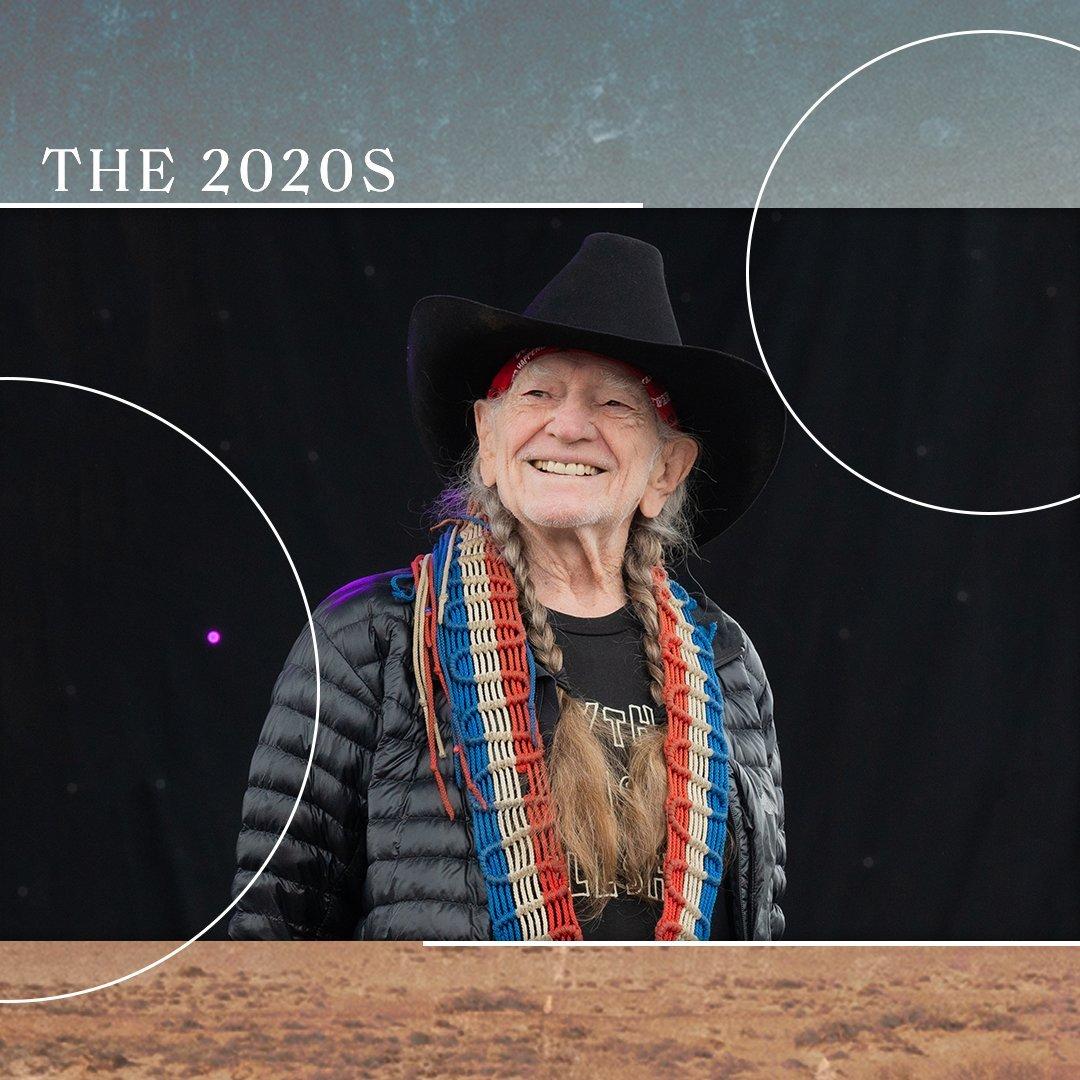

The 2020s

*Willie Nelson performs at the Luck Reunion in 2022 in Luck, Texas | Photo: Jim Bennett/WireImage*

By all available evidence, Nelson is firing on all cylinders in the 2020s. He entered the new decade with 2020's tender First Rose of Spring. Nelson followed that up almost immediately with 2021's That's Life, another excellent tribute to Sinatra.

That year's The Willie Nelson Family reflected his eternal bond with his biological and musical family — Nelsons Amy, Bobbie, Lukas, Micah and Paula. And on April 29, Nelson gave us A Beautiful Time, a gorgeous collection of originals and covers, with an especially touching title track written by Shawn Camp.

"If I ever get home/ I'll still love the road/ Still love the way that it winds," Nelson sings therein. "Now when the last song's been played/ I'll look back and say/ I sure had a beautiful time."

The song carries a tinge of finality, and on the cover, Nelson strolls into the sunset. Does it signal that Nelson is finally winding down? It'd be presumptuous to say so, even though he's numberless albums deep and will turn 90 in 2023.

Despite recent health issues, Nelson is magically, gratefully still on the road. He sings as well, or better, than ever. And his guitar playing alone remains an idiosyncratic force — to say nothing of his still-intact songwriting and interpreting talents.

For all his travails and triumphs, Nelson has remained creatively vital and deeply himself throughout his astonishing career and into his seventh active decade — partly because of his family’s support, partly for staying uncompromising, but also because he never let the old man in.