Photo: Mel Butler

interview

The Jesus And Mary Chain Is Unbroken: Jim Reid On New Album 'Glasgow Eyes' & Their Tempestuous History

"We used to say things that no one ought to say to another human being," says Jim Reid about his brother and musical partner, William. Yet the bond of the Jesus and Mary Chain remains intact — and they're out with a new album, 'Glasgow Eyes,' out March 8.

Aside from an eight-year hiatus, noise-poppers the Jesus and Mary Chain have been together and productive for more than four decades — and stuck to their guns creatively.

How could a hysterical, screaming, improvised onstage meltdown from the mid-'80s — titled "Jesus F—" — possibly foreshadow this?

"The first six months of the band was the only time that you could get away with doing things like that," Jim Reid, their co-leader with brother William, tells GRAMMY.com. "People have paid next to no money to see you. They're not really your fans, because you don't have fans yet. So, you just went out there and did whatever the f— you want."

This involved any number of onstage provocations, fueled by Dutch courage — swinging at the audience, cursing them, playing with their backs to the audience. Of course, the rest is history: they got their act together, at least enough to make masterpieces like 1985's Psychocandy and 1987's Darklands.

After six albums, the chemicals and resentments came to a head in 1999. The Reids wouldn't fire up the project again until 2007, nor release a new album until 2017. But the Mary Chain have forged on.

Despite their tumultuous history, their new album, Glasgow Eyes, out March 8, bears remarkable artistic consistency; it's like the verbal and physical fisticuffs never happened. On tunes like "jamcod," "The Eagles and the Beatles" and "Hey Lou Reid," the Reid brothers' creative compass remains unswerving: Whatever they started doing in 1983, they're still doing it.

"We started because we didn't like the music that we were hearing coming out of the radio," Reid says, calling the pop hits of the day "diarrhea." And if the mainstream still alienates you in 2024, well — look at it all through Glasgow Eyes.

Reid spoke with GRAMMY.com about the past, present and future of the Jesus and Mary Chain.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

In the Glasgow Eyes press release, you said something succinct yet kind of holistic and profound: "Our creative approach is remarkably the same as it was in 1984, just hit the studio and see what happens." Can you expand on that at all?

Well, that's just the way it works. To be honest, when we go into the studio very often we don't have a clue what the record's going to sound like. We've got songs. We don't write in the studio. So, there are a collection of songs, but they could go in any direction.

Generally, we deliberately try not to plan what the record's going to end up [as]. But the only thing that we did see with this record, is we wanted to get out the synths and drum machines. We used things like that in the past, but never quite so upfront.

Did that come from what you were listening to at the time? Darker, older stuff?

We've always listened to that kind of music, but I guess people might not have actually realized that. We love all of that krautrock stuff — Kraftwerk and D.A.F. and Can and all of that. All of those kinds of bands are massively important to us.

It feels like on the earliest Jesus and Mary Chain material, the outré stuff was the yin to pop's yang.

Well, yeah, that's kind of it with us, really. It's the whole package: it's psycho and it's candy.

Regarding that great '80s-ish dark music, what have you been listening to lately?

I'm terrible because I don't listen to much new music. I'm pretty satisfied with my old record collection, and I play kind of a mystery jukebox. Every record I've ever bought since I was 12 is on this computer here, and I just sit with the computer on random play.

I'll just trawl through the records I've had for a long time and I'll dig something out that way. I heard something the other day — it's not a new band, but I can't remember how I heard it. Somebody played it, maybe. A band called Crocodiles. I quite like them. It sounded really good.

When it comes to releasing new music, is the landscape of 2024 destabilizing for you?

Yeah, the musical landscape has always confused us, to be honest with you. Mary Chain never really belonged. We never fit in. We didn't fit in 1984 when we started, and that was why we started.

We started because we didn't like the music that we were hearing coming out of the radio. We thought the radio was ill; we thought it was sick. It was spewing out all of this diarrhea, and we thought, well, it's got to be some better music that can come out of that thing than what we're hearing now.

I'm sorry, but just Kid Creole and the Coconuts — and Spandau Ballet — did not float our boats in 1984 or '85. So it was rubbish then in a kind of way that that's always been the driving force for the Mary Chain. We just think that everybody else's music just isn't good enough. So we will kind of do it to our satisfaction and that's it.

Did you ever meet Mark E. Smith from the Fall back in the day?

I never met Mark E. Smith. He was kind of terrifying from what I can understand. I would've been scared to meet Mark, but loved his band.

I ask because Hex Enduction Hour is one of my favorite albums of all time, and Smith consciously crafted it as a reaction to "bland bastards like… Spandau Ballet."

Oh, God, yeah. That was the dark side of the '80s. Those were the bands that came along and hijacked music and destroyed its soul, I suppose. Take the 1960s and the 1970s. You turned on the radio, and you heard the Rolling Stones singing "I Can't Get No Satisfaction," and everything was good in the world. Same in the '70s, to a certain degree. It was starting to become less so in the '70s, but you could turn on the radio and you could hear Roxy Music or the Sex Pistols or David Bowie.

We got to the '80s and it was like, What the f—? What's going wrong? So, me and William used to sit there and think, Why did we get the '80s? It's not fair. This is our time, and it's the f—ing '80s.

But there were great bands. There were bands like the Fall, the Cocteau Twins, and the Birthday Party, but they were made to take the crumbs that were left over from the main event, if you know what I mean.

One thing I really admire about Glasgow Eyes is that it sounds like you guys. I feel like many bands from certain eras — I won't name any names — slowly bland down and start to sound like each other. Not the Mary Chain.

Well, that's it. That's all we ever try to do: make a Mary Chain record.

A lot of bands… make a record for their audience. And to us, that's the wrong way around. What you do is you make a record for yourself, and if it's any good, you'll get an audience. But as soon as you start making music for other people, you've had it; you're lost. It's the cart before the horse.

I'm sure you've seen that over and over and over, in your decades in the industry.

Yeah, I see it all the time. Everybody thinks, The last record didn't sell as much as we hoped it would. So, what should we do? Who's selling loads of records right now? Oh, U2; let's make a record for the U2 crowd then. In the 1980s, almost every other band sounded like they were trying to be U2.

How did you guys negotiate that territory? I'm sure 30 years ago, the brass was throwing hot new producers at you, or trying to get you on trend bandwagons.

That was it. Our record label were forever trying to run producers down in our throat. Because we produced more or less all of our own music. [2017's] Damage and Joy was the first time we've ever actually brought a producer into the studio, and that was Youth.

We met Daniel Lanois in the late '80s. And I can't remember what album it was, but at the record company's insistence, we met Daniel Lanois and we had this meeting. And he was saying things like, "Yeah, what we'll do is, we won't get a recording studio. We'll get maybe an old church and we'll get all of the gear in there and we'll just get stoned."

We were like, "I'm not sure about this, Daniel." And he was like, "What are you listening to at the moment?" And we said, "Well, we're listening to a lot of hip-hop actually." And he was like, "Hip-hop, are you kidding me?" You could see him looking for the exit thinking, I want to get out.

That's hilarious.

The drugs that I was into at that time, I certainly wasn't interested in sitting getting stoned with Daniel in a church with U2's music playing in the background. I was more into getting off my tits on cocaine listening to stuff like Run-DMC at that time.

I enjoy imagining this.

It was never going to happen. And then we went back to Warner Brothers — it was Rob Dickens running Warner's at that time… and the guy was shouting at us, "You guys are losers. "Yeah, we're losers. But we're losers that are making pretty good records, Rob, so f— off.

There were a few other comedy meetings with producers. I won't go into it, but it was the same deal every time. They would just come along and say all of the opposite of what we had imagined for the record in question — and so it would just never work out.

**The fruitage of this is that you can make whatever kind of music you want in 2024. Take us through the early stages of making Glasgow Eyes, when you had dumped all your toys on the table, as it were, and began trying to make sense of them.**

William's a bit better, but the thing about me is I'm not very technical at all. I love the idea that this technology is out there to be used, but if it was left to me to actually figure out how to use it, it would never get done. But thankfully, that's what studio engineers are for.

We recorded at Mogwai Studio in Glasgow; it's called Castle of Doom. And Tony Doogan's the house engineer there. With Tony, it was like his record collection was probably the same as ours. So, it was going to work.

And then the way it works is you can just say, "That little sort of slightly detuned synth riff that's on 'Der Mussolini' by D.A.F.," And he would go, "Yeah." I don't know how many times in the past when you [reference these things] and [engineers] just go, "Uh, what?"

So it was really good that we had someone in the studio that could speak our language. And he made all of that technology accessible to us. It would be a few sentences to describe what you were looking for — and then, a couple of presses of buttons and twiddles of knobs later, and you'd be hearing what you just described.

Sounds like you had a lot of old-school reference points.

It's weird when you get to my age, yeah, they were old school. But you're thinking old school is probably the noughties. To me, old-school is like the f—ing 1920s. I'm old, man.

So it was things that I considered to be quite modern. I think of Kraftwerk as a futuristic band — because they are. They made records in the early '70s, but to me, it still sounds like new music. I can imagine people in 50 years would listen to Kraftwerk records and think that it had been made then.

The best music is timeless, and they were just way ahead of the game. Way ahead of the game.

At what point did Glasgow Eyes really start to take shape?

Well, that doesn't happen right away. It's the same every time: you start making the record and at some point you think you're losing it. It's not happening. You're thinking, This is going to be embarrassing.

It's almost like you will the record into shape. It goes from this unrecognizable beast into this recognizably Mary Chain [work], and then better and better and better. And then almost like within a couple of days you start to think, F—, this sounds pretty good. And then you start to feel really quite smug about it.

And by the end of it you're like, woohoo, we've done it again. So there's some sort of black magic. It's slightly mystical, but it kind of starts to take shape by itself. But it only happens after some trauma and some sort of serious nervous breakdowns in the middle. And then it just seems to come together. I don't know; it's alchemy.

I can't name too many other bands from your scene who are still grinding it out like this, and staying creative.

There's not many of us left, but Primal Scream are still doing it, man. They're as good as they've ever been. [Singer] Bobby [Gillespie]'s our old drummer and he's rocking it out. And I went to see them a few weeks ago and it's great. He's still great. He's still going.

Growing up with the Mary Chain, I remember reading stories about how you guys had a… tempestuous relationship with your audience. Which included a lot of provocation from the stage. Is that true?

Well, it is, but a lot of it was insecurity on our part.

Well, it was a couple of things. One, we'd never been in any other bands before. Lou Reed did a [1980] album called Growing Up in Public; well, that was us. We made all of our mistakes in front of an audience, and often in front of cameras, and often on TV shows.

But we were very, very insecure, and I was incredibly shy. And the only way that I could get the nerve to get on stage was to get wasted. I used to swig down bottles of whiskey before I went onstage — then, I'd be up there, swinging at people and stuff like that. Or telling the audience to go f— themselves.

But it was all based on my own insecurity and that was it. I was unable to deal with the situation that I found myself in. And we quickly learned that you couldn't continue doing that. So we found a way to make it work.

Did you guys really play with your backs to the audience?

Yeah. We were literally so embarrassed and so awkward on stage that we would turn around and every now and again, glimpse over our shoulders at the audience, like, He's still here. Oh, God.

I'll leave you with this: how has your creative relationship with William been over the past several decades?

Well, at the beginning, we were so in tune with each other. It was like we totally, totally agreed with everything about what direction the band ought to be taking.

The band broke up in 1998 for a while, and that was because we just totally lost touch with each other. We used to argue about creative decisions. By 1998, we were arguing about anything.

We couldn't stand being in the same room as each other. And it was a very messy breakup. In 1998, we were trying to f—ing eradicate each other. And then for a couple of years, we couldn't talk. The band broke up, we didn't speak to each other.

[In 2007], the band got back together. Our relationship healed a bit. It's better now than I think it's been for years.

We argue. We always will. We always have. But it's more productive and it's less nasty. And towards 1998, we used to say things that no one ought to say to another human being. And once you've said those kind of things, they can never be taken back.

And I know there are things that he said to me and I've said to him — that even though the wounds have healed, I'm still kind of thinking, But f— you, man. I remember when you said that night.

So now when it's getting that bad, you think, Oh, we're approaching that line, step back. So it works much better now than it used to. We're OK.

Lou Reed's Berlin Is One Of Rock's Darkest Albums. So Why Does It Sound Like So Much Fun?

Photo: Kevin C. Cox/Getty Images

news

2024 Paris Olympics Opening Ceremony: Watch Celine Dion, Lady Gaga, Gojira & More Perform

The Olympic Games have long featured iconic musical performances – and this year is no different. Check out the performers who took the stage in the City of Light during the 2024 Olympics Opening Ceremony in Paris.

The 2024 Paris Olympics came to life today as the Parade of Nations glided along the Seine River for the opening ceremony. The opening spectacular featured musical performances from Lady Gaga, Celine Dion, and more. Earlier in the week, some of music’s biggest names were also spotted in the city for the Olympics, including Olympics special correspondent Snoop Dogg, BTS' Jin, Pharrell Williams, Tyla, Rosalía, and Ariana Grande.

Read More: When The GRAMMYs & Olympics Align: 7 Times Music's Biggest Night Met Global Sports Glory

Below, see a full breakdown of some of the special musical moments from the 2024 Paris Olympics opening ceremony.

Lady Gaga

In a grand entrance, Lady Gaga emerged behind a heart-shaped plume of feathers on the golden steps of Square Barye, captivating the audience with her cover of the French classic "Mon truc en plumes." Accompanied by cabaret-style background dancers, she flawlessly belted out the song, executed impressive choreography, and even played the piano.

Lady Gaga’s connection to the song is notable, as Zizi Jeanmarie, the original artist, starred in Cole Porter’s musical "Anything Goes," which was Lady Gaga’s debut jazz release.

"Although I am not a French artist, I have always felt a very special connection with French people and singing French music — I wanted nothing more than to create a performance that would warm the heart of France, celebrate French art and music, and on such a momentous occasion remind everyone of one of the most magical cities on earth — Paris," Lady Gaga shared on Instagram.

Celine Dion

Closing out the ceremony with her first performance in four years since being diagnosed with stiff-person syndrome, Celine Dion delivered a stunning rendition of Edith Piaf’s everlasting classic, "L’Hymne à l’amour" from the Eiffel Tower. Her impressive vocals made it seem as though she had never left.

This performance marked Dion’s return to the Olympic stage; she previously performed "The Power of the Dream" with the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra and composer David Foster for the 1996 Olympics.

Axelle Saint-Cirel

Performing the National Anthem is no small feat, yet French mezzo-soprano Axelle Saint-Cirel knocked it out of the park.

Dressed in a French-flag-inspired Dior gown, she delivered a stunning rendition of "La Marseillaise" from the roof of the Grand Palais, infusing the patriotic anthem with her own contemporary twist.

With the stirring lyrics, "To arms, citizens! Form your battalions. Let’s march, let’s march," Saint-Cirel brought the spirit of patriotism resonated powerfully throughout the city.

Gojira

Making history as the first metal band to perform at the Olympics Opening Ceremony is just one way Gojira made their mark at the event.

The French band took the stage at the Conciergerie, a historic site that once housed French kings during medieval times and later became a prison during the French Revolution, famously detaining Marie Antoinette – Creating a monumental moment as the first metal band to perform at the ceremony, but also stirring the pot as they used the chance to nod toward politics.

Performing a revamped version of "Ah! Ça Ira," an anthem that grew popular during the French Revolution, the artists aren’t new to using their songs as a vehicle for political messages. The GRAMMY-nominated group are outspoken about issues concerning the environment, particularly with their song, "Amazonia," which called out the climate crisis in the Amazon Rainforest. Using music to spread awareness about political issues is about as metal as it gets.

Aya Nakamura

Currently France’s most-streamed musician, Aya Nakamura went for gold in a striking metallic outfit as she took the stage alongside members of the French Republican Guard. As there were showstopping, blazing fireworks going off behind her, she performed two of her own hit songs, "Pookie" and "Djadja," then followed with renditions of Charles Aznavour’s "For Me Formidable" and "La Bohème."

Although there was backlash regarding Nakamura’s suitability for performing at the ceremony, French President Emmanuel Macron dismissed the criticism. "She speaks to a good number of our fellow citizens and I think she is absolutely in her rightful place in an opening or closing ceremony," Macron told the Guardian.

Latest News & Exclusive Videos

2024 Paris Olympics Opening Ceremony: Watch Celine Dion, Lady Gaga, Gojira & More Perform

Ice Spice Is The Drill Queen On 'Y2K!': 5 Takeaways From Her Debut Album

New Music Friday: Listen To New Songs From Halsey, MGK And Jelly Roll, XG & More

Watch Young MC Win Best Rap Performance In 1990

The Red Clay Strays Offer A New Kind Of Religion With 'Made By These Moments'

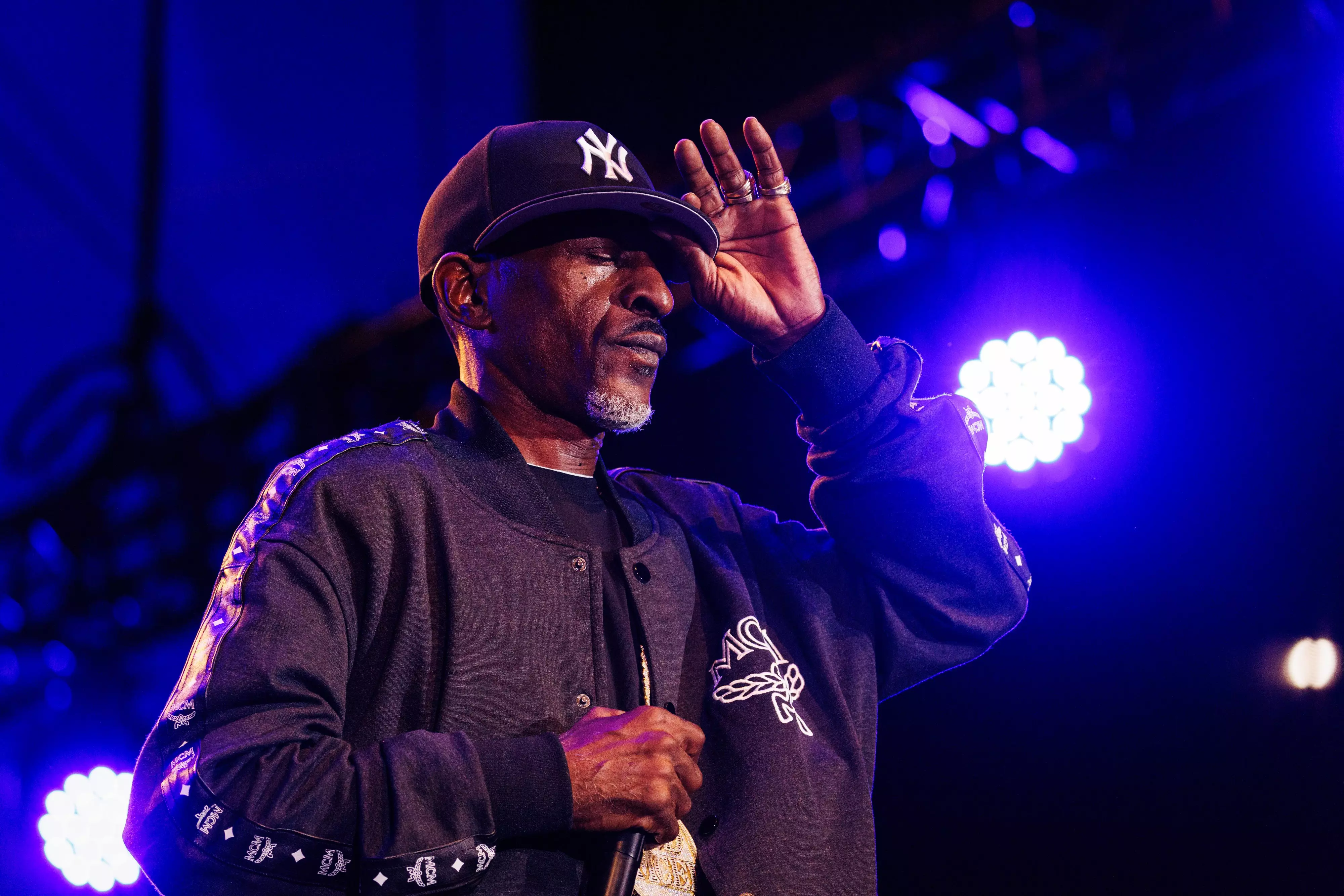

Photo: Matt Jelonek/Getty Images

list

Ice Spice Is The Drill Queen On 'Y2K!': 5 Takeaways From Her Debut Album

The 10-track LP clocks in at just under 24 minutes, but it's packed with insanely quotable one-liners, star-studded collaborations, and bold statements.

Since Ice Spice first caught our attention two summers ago, she's been nothing short of a rap sensation. From viral hits like her breakout "Munch (Feelin' U)," to co-signs from Drake and Cardi B, to a Best New Artist nomination at the 2024 GRAMMYs, the Bronx native continues to build on her momentum — and now, she adds a debut album to her feats.

Poised to be one of the hottest drops of the summer, Y2K! expands on Ice Spice's nonchalant flow and showcases her versatility across 10 unabashedly fierce tracks. She dabbles in Jersey club on "Did It First," throws fiery lines on lead single "Think U the S— (Fart)," and follows the album's nostalgic title with an interpolation of an early '00s Sean Paul hit on "Gimmie a Light."

Y2K! also adds more star-studded features to Ice Spice's catalog, with Travis Scott, Gunna and Central Cee featuring on "Oh Shh...," "B— I'm Packin'," and "Did It First," respectively. At the helm is producer RiotUSA, Ice Spice's longtime friend-turned-collaborator who has had a hand in producing most of the rapper's music — proving that she's found her stride.

As you stream Ice Spice's new album, here are five key takeaways from her much-awaited debut, Y2K!.

She Doubles Down On Bronx Drill

Ice Spice is one of the few ladies holding down the New York drill scene on a mainstream level. She's particularly rooted in Bronx drill, a hip-hop subgenre known for its hard-hitting 808s, high-hats and synthesizers — and according to the sounds of Y2K!, it’s seemingly always going to be part of her artistry.

"It's always time to evolve and grow as an artist, so I'm not rushing to jump into another sound or rushing to do something different," Ice Spice told Apple Music of her tried-and-true musical style.

While Y2K! may not be as drill-driven as her debut EP Like…?, the album further hints that Ice isn't ready to retire the sound anytime soon. The subgenre is the dominant force across the album's 10 tracks, and most evident in "Did It First," "Gimmie a Light" and "BB Belt." Even so, she continues her knack for putting her own flair on drill, bringing elements of trap and electronic music into bops like "Oh Shhh…" and "Think U the S— (Fart)."

She Recruited Producers Old & New

Minus a few tunes, all of Ice Spice's songs start off with her signature "Stop playing with 'em, Riot" catchphrase — a direct nod to her right-hand man RiotUSA. Ice and Riot met while attending Purchase College in New York, and they've been making music together since 2021's "Bully Freestyle," which served as Ice's debut single. "As I was growing, she was growing, and we just kept it in-house and are growing together," Riot told Finals in a 2022 interview.

Riot produced every track on Like.. ? as well as "Barbie World," her GRAMMY-nominated Barbie soundtrack hit with Nicki Minaj. Their musical chemistry continues to shine on Y2K!, as Riot had a hand in each of the LP's 10 tracks.

In a surprising move, though, Ice doesn't just lean on Riot this time around. Synthetic, who worked on Lil Uzi Vert's GRAMMY-nominated "Just Wanna Rock," brings his Midas touch to "Think U the S—." Elsewhere, "B— I'm Packin'" is co-produced by Riot, Dj Heroin, and indie-pop duo Ojivolta, who earned a GRAMMY nomination in 2022 for their work on Kanye West's Donda. But even with others in the room, Riot's succinct-yet-boisterous beats paired with Ice's soft-spoken delivery once again prove to be the winning formula.

She Loves Her Y2K Culture

Named after Ice Spice's birthdate (January 1, 2000), her debut album celebrates all things Y2K, along with the music and colorful aesthetics that defined the exciting era. To drive home the album's throwback theme, Ice tapped iconic photographer David LaChapelle for the cover artwork, which features the emcee posing outside a graffiti-ridden subway station entrance. LaChapelle's vibrant, kitschy photoshoots of Mariah Carey, Lil' Kim, Britney Spears, and the Queen of Y2K Paris Hilton became synonymous with the turn of the millennium.

True to form, Y2K!'s penultimate song and second single "Gimmie a Light" borrows from Sean Paul's "Gimme the Light," which was virtually inescapable in 2002. "We really wanted to have a very authentic Y2K sample in there," Ice Spice said in a recent Apple Music Radio interview with Zane Lowe. Not only does the Sean Paul sample bring the nostalgia, but it displays Ice's willingness to adopt new sounds like dancehall on an otherwise drill-heavy LP.

Taking the Y2K vibes up another notch, album closer "TTYL," a reference to the acronym-based internet slang that ruled the AIM and texting culture of the early aughts. The song itself offers fans a peek insideIce's lavish and exhilarating lifestyle: "Five stars when I'm lunchin'/ Bad b—, so he munchin'/ Shoot a movie at Dunkin'/ I'm a brand, it's nothin.'"

She's A Certified Baddie

Whether she's flaunting her sex appeal in "B— I'm Packin'" or demanding potential suitors to sign NDAs in "Plenty Sun," Ice exudes confidence from start to finish on Y2K!.

On the fiery standout track "Popa," Ice demonstrates she's in a league of her own: "They ain't want me to win, I was chosen/ That b— talkin' s—, she get poked in/ Tell her drop her pin, we ain't bowlin'/ Make them b—hes sick, I got motion." And just a few songs later, she fully declares it with "BB Belt": "Everybody be knowin' my name (Like)/ Just want the money, I don't want the fame (Like)/ And I'm different, they ain't in my lane."

For Ice, "baddie" status goes beyond one's physical attributes; it's a mindset she sells with her sassy delivery and IDGAF attitude.

She's Deep In Her Bag

In album opener "Phat Butt," Ice boasts about rocking Dolce & Gabbana, popping champagne, and being a four-time GRAMMY nominee: "Never lucky, I been blessed/ Queen said I'm the princess/ Been gettin' them big checks in a big house/ Havin' rich sex," she asserts.

Further down the track list, Ice Spice firmly stands in her place as rap's newest queen. In "BB Belt," she raps, "I get money, b—, I am a millionaire/ Walk in the party, everybody gon' stare/ If I ain't the one, why the f— am I here, hm?"

Between trekking across the globe for her first headlining tour and lighting up the Empire State Building orange as part of her Y2K! album rollout, Ice Spice shows no signs of slowing down. And as "BB Belt" alludes, her deal with 10K Projects/Capitol Records (she owns her masters and publishing) is further proof that she's the one calling the shots in her career.

Whatever Ice decides to do next, Y2K! stands as a victory lap; it shows her prowess as drill's latest superstar, but also proves she has the confidence to tackle new sounds. As she rapped in 2023's "Bikini Bottom," "How can I lose if I'm already chose?" Judging by her debut album, Ice Spice is determined to keep living that mantra.

More Rap News

Ice Spice Is The Drill Queen On 'Y2K!': 5 Takeaways From Her Debut Album

Watch Young MC Win Best Rap Performance In 1990

On Rakim's 'G.O.D's Network (REB7RTH)' The MC Turned Producer Continues His Legacy With An All-Star Cast

5 Ways Mac Dre's Final Living Albums Shaped Bay Area Rap

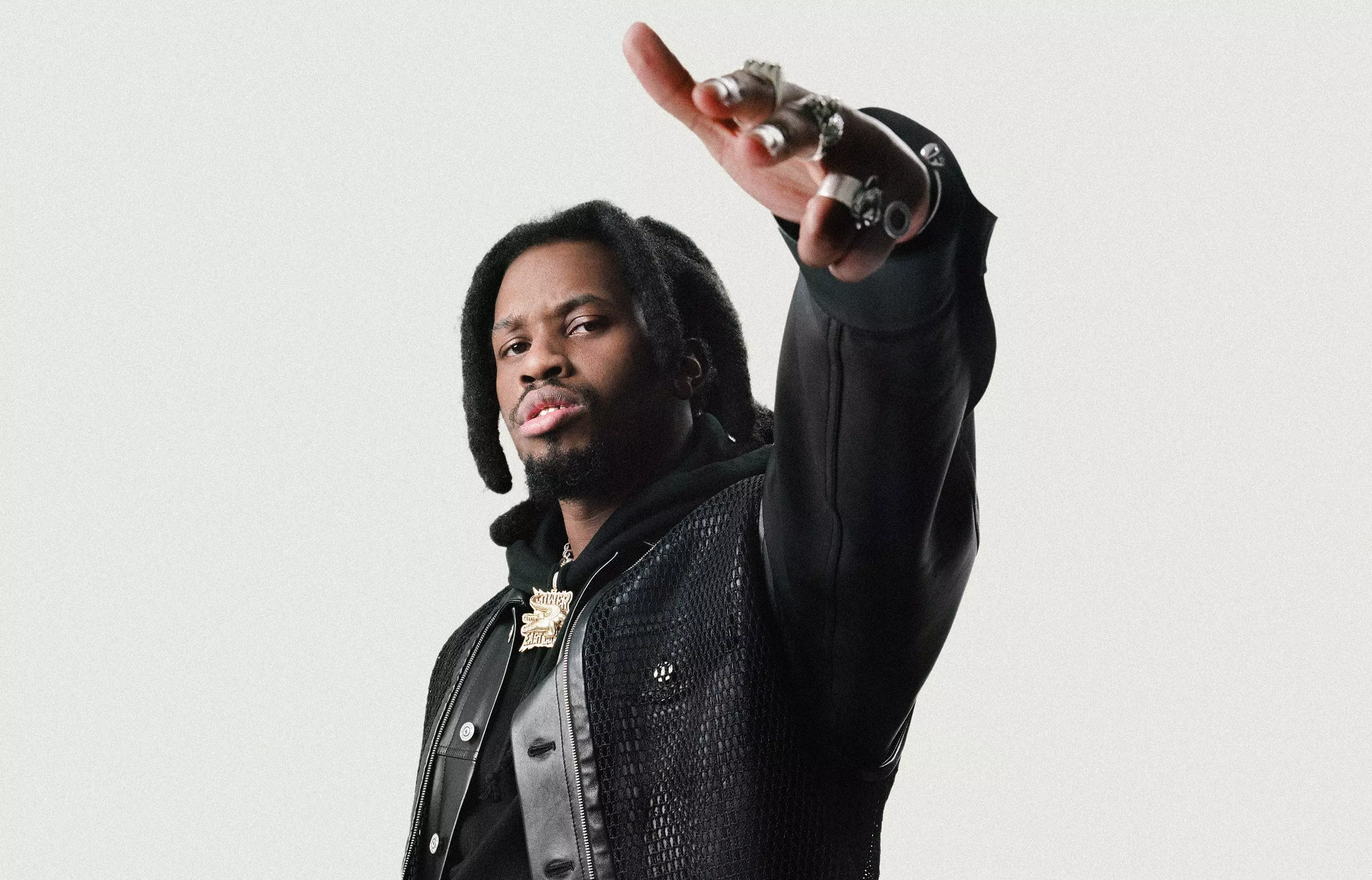

Denzel Curry Returns To The Mischievous South: "I've Been Trying To Do This For The Longest"

Photo: Brett Carlsen/Getty Images for Spotify

news

New Music Friday: Listen To New Songs From Halsey, MGK And Jelly Roll, XG & More

As July comes to a close, there's another slew of new musical gems to indulge. Check out the latest albums and songs from Paris Hilton and Meghan Trainor, Mustard and more that dropped on July 26.

July has graced us with a diverse array of new music from all genres, lighting up dance floors and speakers everywhere.

The last weekend of the month brings exciting new collaborations, including another iconic track from Calvin Harris and Ellie Goulding, as well as a fierce team-up from Paris Hilton and Meghan Trainor. Halsey and Muni Long offered a taste of their forthcoming projects, while Jordan Davis and Miranda Lambert each delivered fun new country tunes.

In addition to fresh collabs and singles, there's a treasure trove of new albums to uncover. Highlights include Ice Spice's Y2K!, Rakim's G.O.D., Sam Tompkins' hi, my name is insecure, Wild Rivers' Never Better, Tigirlily Gold's Blonde, and kenzie's biting my tongue.

As you check out all the new music that dropped today, be sure you don't miss these 10 tracks and albums.

mgk & Jelly Roll — "Lonely Road"

Although fans anticipated Machine Gun Kelly's next release to mark his return to hip-hop, no one seems to be complaining about "KellyRoll." Embracing the trend of venturing into the country genre, mgk teams up with fellow GRAMMY-nominated artist Jelly Roll on their newest track, "Lonely Road."

The genre-blending track interpolates John Denver's classic "Take Me Home, Country Roads." However, unlike Denver's sentimental ode to the simplicity of rural life, mgk and Jelly Roll reinterpret the track through the lens of romantic relationships that have come to a, well, lonely end.

As mgk revealed in an Instagram post, "Lonely Road" was a labor of love for both him and Jelly Roll. "We worked on 'Lonely Road' for 2 years, 8 different studios, 4 different countries, changed the key 4 times," he wrote. "We finally got it right."

Halsey — "Lucky"

In another interpolation special, Halsey samples not one but two classics in their latest single, "Lucky." The song's production features elements of Monica's 1999 hit "Angel of Mine," while the chorus flips Britney Spears' fan-favorite "Lucky" into a first-person narrative.

While Halsey has always been a transparent star, their next project is seemingly going to be even more honest than their previous releases. After first revealing their journey with lupus with the super-personal "The End" in June, "Lucky" further details their struggles: "And I told everybody I was fine for a whole damn year/ And that's the biggest lie of my career."

Though they haven't revealed a release date for their next project, Halsey referred to her next era as a "monumental moment in my life" in an Instagram post about the "Lucky" music video — hinting that it may just be their most powerful project yet.

Read More: Everything We Know About Halsey's New Album

Paris Hilton & Meghan Trainor — "Chasin'"

Ahead of Paris Hilton's forthcoming album, Infinite Icon — her first in nearly 20 years — the multihyphenate unveiled another female-powered collaboration, this time with Meghan Trainor. Co-produced by Sia, "Chasin'" is a lively pop anthem about discovering self-worth in romantic relationships and finding the strength to walk away from toxicity.

"She is the sister I always needed and when she calls me sis, I die of happiness inside," Trainor told Rolling Stone about her relationship with Hilton. Coincidentally, Trainor first wrote the track with her brother, Ryan, but the pop star was waiting for the right collaborator to hop on the track — and Hilton was just that.

"We made something truly iconic together," Trainor added. "It was a bucket list dream come true for me."

Empire Of The Sun — 'Ask That God'

A highly awaited return to music after eight years, Australian electro-pop duo Empire Of The Sun are back with their fourth studio album, Ask That God.

"This body of work represents the greatest shift in consciousness our world has ever seen and that's reflected in the music," says member Lord Littlemore in a press statement.

Like their previous work that transports listeners to a different universe, this album continues that tradition with trancey tracks like lead single "Changes" and the thumping title track. Ask That God offers a chance to reflect on the blend of reality and imagination, while also evoking the radiant energy of their past songs.

Calvin Harris & Ellie Goulding — "Free"

Dance music's collaborative powerhouse, Calvin Harris and Ellie Goulding, are back with another summer hit. Their latest track, "Free," marks the fourth collaboration between the duo — and like their past trilogy of hits, the two have another banger on their hands.

The track debuted earlier this month at Harris' show in Ibiza, where Goulding made a surprise appearance to perform "Free" live. With Harris delivering an infectious uptempo house beat and Goulding's silky vocals elevating the track, "Free" proves that the pair still have plenty of musical chemistry left.

Post Malone & Luke Combs — "Guy For That"

Post Malone's transition into country music has been anything but slow; in fact, the artist went full-throttle into the genre. The New York-born, Texas-raised star embraced his new country era with collaborations alongside some of the genre's biggest superstars, like Morgan Wallen and Blake Shelton. Continuing this momentum as he gets closer to releasing F-1 Trillion, Post Malone teams up with Luke Combs for the new track "Guy For That."

The catchy collaboration tells the story of a relationship that has faded, where the protagonist knows someone who can fix almost anything, except for a broken heart. It's an upbeat breakup song that, like Post's previous F-1 Trillion releases, can get any party going — especially one in Nashville, as Malone and Combs did in the track's music video.

Forrest Frank & Tori Kelly — "Miracle Worker"

Just one month after Surfaces released their latest album, good morning, the duo's Forrest Frank unveiled his own project, CHILD OF GOD — his debut full-length Christian album. Among several features on the LP, one of the standouts is with GRAMMY-winning artist Tori Kelly on the track "Miracle Worker."

Over a plucky electric guitar and lo-fi beats, Frank and Kelly trade verses before joining for the second chorus. Their impassioned vocals elevate the song's hopeful prayer, "Miracle Worker make me new."

Their collaboration arrives just before both artists hit the road for their respective tours. Frank kicks his U.S. trek off in Charlotte, North Carolina on July 31, and Kelly starts her world tour in Taipei, Taiwan on Aug. 17.

XG — "SOMETHING AIN'T RIGHT"

Since their debut in 2022 with "Tippy Toes," Japanese girl group XG has been making waves and showing no signs of slowing down. With their first mini album released in 2023 and now their latest single, "SOMETHING AIN'T RIGHT," the group continues to rise with their distinctive visuals and infectious hits.

The track features a nostalgic rhythm reminiscent of early 90s R&B, showcasing the unique personalities of each member. As an uptempo dance track, it's designed to resonate with listeners from all across the globe.

"SOMETHING AIN'T RIGHT" also serves as the lead single for XG's upcoming second mini album, set to release later this year.

Mustard — 'Faith of a Mustard Seed'

For nearly 15 years, Mustard has been a go-to producer for some of rap's biggest names, from Gucci Mane to Travis Scott. On the heels of earning his first Billboard Hot 100 chart-topper as a producer with Kendrick Lamar's "Not Like Us," he's back with his own collaboration-filled project.

Faith of a Mustard Seed features a robust 14-song track list with contributions from Vince Staples, Lil Yachty, Charlie Wilson, and more. The LP marks Mustard's fourth studio album, and first since 2019's Perfect Ten.

In an interview with Billboard, Mustard shared that the album's title is an ode to late rapper Nipsey Hussle, who suggested the title during one of their final conversations before his untimely death in 2019. And once "Not Like Us" hit No. 1, Mustard knew it was time to release the long-in-the-making album.

Latest News & Exclusive Videos

2024 Paris Olympics Opening Ceremony: Watch Celine Dion, Lady Gaga, Gojira & More Perform

Ice Spice Is The Drill Queen On 'Y2K!': 5 Takeaways From Her Debut Album

New Music Friday: Listen To New Songs From Halsey, MGK And Jelly Roll, XG & More

Watch Young MC Win Best Rap Performance In 1990

The Red Clay Strays Offer A New Kind Of Religion With 'Made By These Moments'

Photo: Robby Klein

interview

The Red Clay Strays Offer A New Kind Of Religion With 'Made By These Moments'

As the rising — and rousing — country group release their second album, the Red Clay Strays' Brandon Coleman and Drew Nix detail the hard-fought journey that's inspired them to deliver a hopeful message with their music.

Faith has been a driving force behind Alabama band the Red Clay Strays, both in their music and in their journey to stardom. With their new album, Made By These Moments, the quintet leans into that foundation even further, giving listeners a look into their walk with God and road to redemption — all of which has helped them become one of country music's most exciting breakout acts.

Despite the divine influence, lead singer Brandon Coleman insists they're not a Christian band. And their music proves that: The Strays' sound delves as much into high-flying Southern rock and gritty delta blues as it does country, sounding like Waylon Jennings or Johnny Cash one minute, then Lynyrd Skynyrd or Elvis Presley the next. As Coleman insists, what's most important to the group is making music that resonates.

"Most of the time we're not setting out to write a worship song… or anything like that," he tells GRAMMY.com. "We don't want to be a Christian band or even a country band — we just want to make music, plain and simple."

Born out of a cover band in 2016, The Strays grinded it out for years in bars around Mobile and the Deep South before hitting a breakthrough with 2022's independently released Moment Of Truth. Their budding acclaim led to opening slots with Elle King, Dierks Bentley, Eric Church and Old Crow Medicine Show, their first chart hit with "Wondering Why," and debuts on the Grand Ole Opry stage and on national television. And just one week before Made By These Moments arrived, the group were featured on the star-studded soundtrack for Twisters.

That all culminated in them signing with RCA Records in April 2024 and working with producer Dave Cobb, who helped the Red Clay Strays deliver their most polished and faith-focused set to date with Made By These Moments. Its 11 songs serve as a blueprint of how with hard work, patience and God in your corner no obstacle is too big to overcome. The band navigates everything from questioning oneself ("No One Else Like Me") and searching for purpose ("Drowning," "Devil In My Ear") to discovering and becoming grounded in faith ("I'm Still Fine," "On My Knees") and growing into the best version of yourself as a result ("Made By These Moments," "God Does").

"We're not trying to go out and preach to anybody, we're just singing songs about our lives and people can listen if they want," Coleman asserts. "I've had many people who aren't spiritual or religious come up to me and say that our music has gotten them to think and reevaluate how they go about their daily lives. That's all you can ask for if you're trying to inspire or help people with your music."

Before the release of Made By These Moments, The Strays' Brandon Coleman and Drew Nix spoke with GRAMMY.com about how faith influences their music, the album's range of inspirations, and more.

You guys haven't shied away from making your faith a focal point of your music. Mind telling me about the roots of that influence, particularly with how it relates to the 11 songs on this new record?

Brandon Coleman: I mean, God's really the driving force in all of it. He's why we do this. Everyone's wondering why they were put here on Earth and what their purpose is. Once you're able to get an idea for what that is, that's often what you end up doing. Our music is about our lives and living on the road, and God is a big part of all of it.

Drew Nix: When God gives you a gift you have to use it or it's wasted, right? The biblical things we talk about in our music are lessons that we've learned growing up. It's such complex and simple truths all wrapped into one, which makes it really easy to write about. There's victory and strife and everything else you go through in life. It leaves us thanking God at the end of each and every day for giving us another one.

It sounds like rather than faith seeping into music that it's simply been ingrained in your DNA long before you started making music?

Coleman: Exactly. We're always looking to put God above ourselves.

Nix: When I'm writing songs like "Drowning" — a song that came about when I felt like I couldn't get ahead in life because I kept slipping and falling — it's very therapeutic too.

Another example is "Devil In My Ear," which sees me dealing with a close friend and someone I considered to be family's suicide. It was our drummer's brother Jacob, who was an unofficial member of the band and one of the best musicians we knew. He took his own life in 2020, so that song was me trying to deal with that. The only thing I could come up with at the time was that the devil got in his ear because he really had it made — he was an incredible musician with a loving family around him. It just didn't make any sense to me until writing that song.

I obviously hate to hear that, but at the same time I firmly believe that one of the most beautiful things about music is the positivity that can radiate from even the most tragic of circumstances. It's a way to make others who've gone through similar experiences feel seen and not alone, easing the weight of the trauma that comes with it in the process. "Devil In My Ear" is a perfect example of that.

Nix: Not feeling alone, that's a huge part of it. On a related note, the song "Made By These Moments" touches on exactly what you're talking about. We go through all these horrible and beautiful things in our lives that make us who we are. It's also one of the songs that finally brings up the mood on the album as well.

Coleman: That's the beauty of this album. It starts out great a lot of times like life does. It starts with a good rock song before taking you down into the dark places that we all go to with "Drowning" and "Devil In My Ear." Then you come out of that with "I'm Still Fine" realizing "Oh crap, I'm down in the valley but I'm still fine because God's still got me" ahead of rejoicing with "On My Knees," and realizing that getting through all these bad things is what makes us stronger with "Made By These Moments." Closing out the album with a perfect ending is "God Does," a gentle reminder that even though you may not think something is possible, God does.

It's like a roller coaster ride to redemption.

Coleman: Addiction and survival, too — all of it.

You mentioned "Drowning" a moment ago, which is one of my favorites on the record due to both its message and Brandon's high-powered vocals — particularly during its chorus — that remind me a lot of Chris Stapleton. It's a little bit country, blues and rock with a heck of a lot of emotion.

Coleman: Thank you. "Drowning" was originally written in A, so we were singing the chorus, but it wasn't quite up there note wise. I felt like we had a lot of room to keep going up, so we walked it up to a C so it has more of that screaming vibe to it, which definitely helped the song.

It feels fitting and reminds me of when we were struggling in 2020 and 2021 and were driving for Uber. I finally scraped up $100 to get my car's oil changed. It was supposed to be free, but the place ended up charging me a $40 fee before convincing me to buy new air filters too, to which I said "go ahead" because I just can't say no. What was a $15 air filter I ended up getting charged $75 for, taking my would be free oil change up over the $100 I'd just saved up.

I remember leaving there, going back home and kicking this drawer that I'd picked up on the side of the road. I ended up breaking it and screaming at the top of my lungs, and that's what the big notes in the chorus of "Drowning" remind me of.

If it makes you feel any better I literally got my car's oil changed this morning and they got me on the upcharge for an air filter too.

Coleman: It does, but it hits a lot different when you only have $100 to your name.

Absolutely. And thankfully that's something y'all aren't having to deal with anymore. What a difference a couple years can make!

Coleman: Even going through all that, despite how hard it was, we were never hopeless. We all just looked at it as going through a battle. We still had faith in God all the way, even when it was very hard to, which was very scary and stressful. People always say to never quit and to never give up, and that's turned out to be true for us too.

That leads me to "God Does." There's a lot of rockin' tunes on this record, but that song stands out from the rest, both in its message and the stripped back format you recorded it in. Was it always your plan to compose it like that or did you ever have a plan to give it a similar treatment to the rest of this project?

Coleman: I can't speak for Drew, but that was always my idea of how it would be. Working with Dave, he has his ideas too, and in the studio they all mesh together as we figure out and create it. He changed the whole beat up on ["God Does"] and gave the song more of a waltz-y feel that completely transformed it for the better, in my opinion.

Nix: I had a country-er imagination for it when I wrote and demoed it. I bought a pedal steel about a year ago to have it go more of the country route, but the way it turned out is better than I ever imagined.

Coleman: I like the way Drew came up with it, too. I actually still have that work tape on my phone because I remember how that song helped me out during that time of uncertainty and struggling. We played a show in Baldwin County [Alabama] somewhere and were using Jacob's old bus because our's was broken down. One of its tires went flat, so we had to leave it at the venue. Drew and I returned the next day to change the tire so we could get home. It was then that Drew told me about this new song he'd just written called "God Does."

I don't know if he knew, but I was sitting there just trying to hide my tears as I listened to it because of being in that time of life of not knowing what to do and feeling hopeless. That song came along at a very good time and really changed my trajectory mentally.

Latest News & Exclusive Videos

2024 Paris Olympics Opening Ceremony: Watch Celine Dion, Lady Gaga, Gojira & More Perform

Ice Spice Is The Drill Queen On 'Y2K!': 5 Takeaways From Her Debut Album

New Music Friday: Listen To New Songs From Halsey, MGK And Jelly Roll, XG & More

Watch Young MC Win Best Rap Performance In 1990

The Red Clay Strays Offer A New Kind Of Religion With 'Made By These Moments'