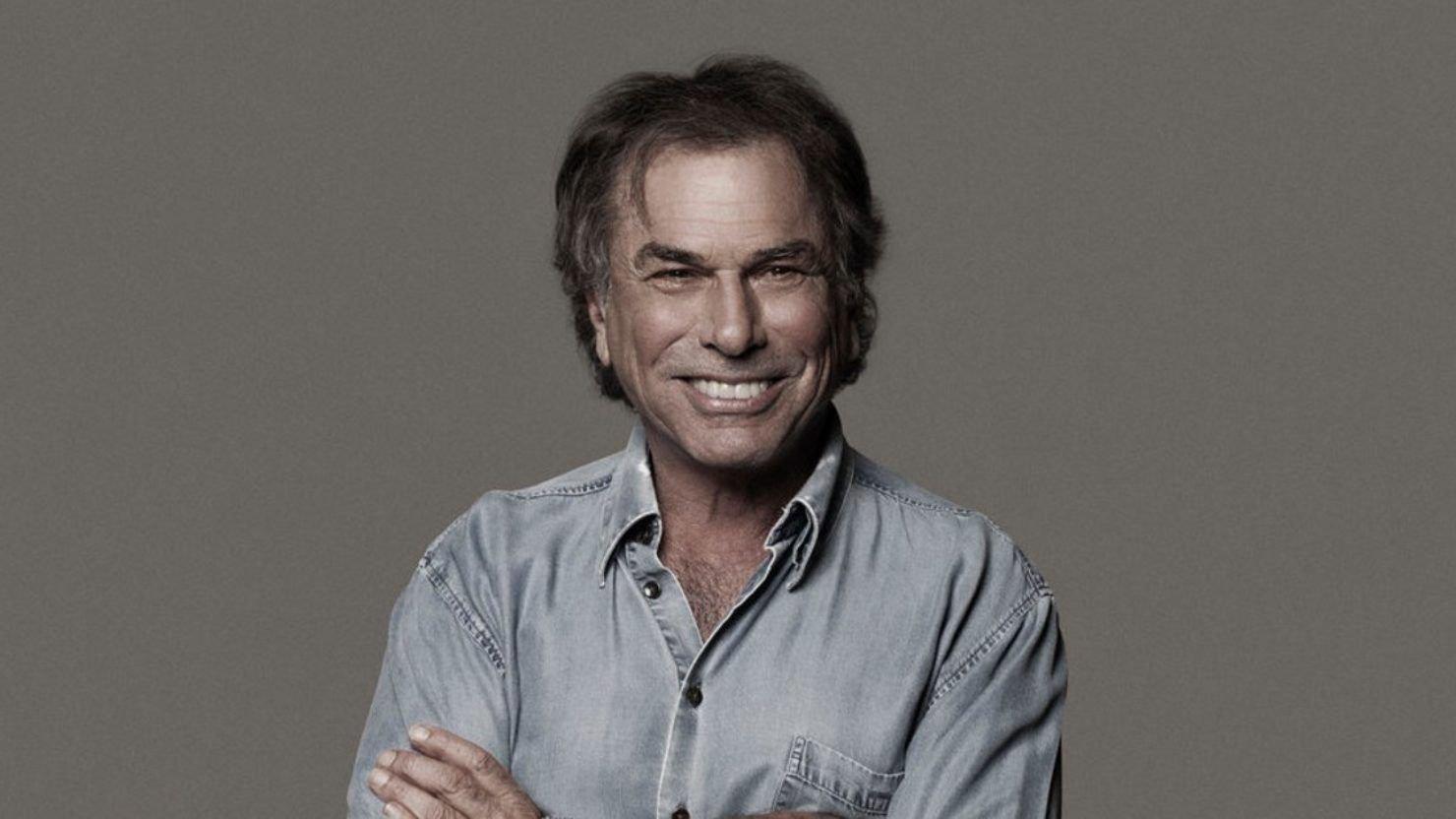

Photo: Scott Simontacchi

Jim Lauderdale

news

Songwriter's Songwriter Jim Lauderdale On New Album 'Hope,' Missing Robert Hunter & Why There's No Shortage Of Great Music Today

Two-time GRAMMY winner Jim Lauderdale may not be a household name, but his songs have been recorded by everyone from George Strait to Blake Shelton to the Chicks. His heartening new album, 'Hope,' contains one of his last collaborations with Robert Hunter

Even if you never get to Jim Lauderdale's thirty-somethingth album, he hopes you at least look at the cover. It's a serene, gently surreal painting by Maureen Hunter, the widow of Grateful Dead co-lyricist Robert Hunter. To him, even if record shoppers merely see that—with the word "Hope" in block letters above that—at least he'll have made a momentary impression on their hearts.

"We all need that, no matter who we are and what's going on," the songwriter's songwriter, who has won two GRAMMYs and had songs recorded by Elvis Costello, Patty Loveless, Gary Allan and others, tells GRAMMY.com. "This is as bleak as things have been for many of us in life. Some of us have seen worse, and much harder and more terrible times, but for a lot of us, this period has been pretty bad."

For his part, Lauderdale has been hanging in there, practicing tai chi, eating medicinal mushrooms to stay strong, and writing more than he ever has. This state of mind is refracted throughout Hope, which was released July 30 via Yep Roc Records. Its tunes, like "The Opportunity to Help Somebody Through It," "Breathe Real Slow" and "Joyful Noise," go beyond chord progressions and lyrics: They have legitimate therapeutic value.

'Hope' album art. Painting by Maureen Hunter.

And he had one of the most spine-tinglingly primeval lyricists on the case: the Grateful Dead's co-lyricist Robert Hunter, who wrote the words to classics like "Dark Star," "Ripple" and "China Cat Sunflower" before dying in 2019 at 78. He wrote more than a hundred songs with Lauderdale over the years; "Memory," included here," was one of the last.

"I really miss him very much and feel his presence every day and think about him every day," Lauderdale says of his old friend and collaborator. "I think he was the most interesting and intelligent guy I ever met." Read on for more expressions about Hunter, Hope and how Lauderdale keeps his bearings in an era of relentless disasters.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Hey, Jim.

Hi! This is Jim Lauderdale. I'm sorry I can't get to your call right now, but please leave your name and number. It's really important to me, everybody. Each and every one of you. I promise I'll get back to you soon. Thanks. Beep! Your mailbox is full and cannot take messages at this time. [Breaks into giggles.]

Nah, I'm kidding. I love to do that to unsuspecting people.

Wow. I'm hundreds of interviews deep, but that's a first. What records are you checking out lately?

You know, there's a group from Louisiana called Feufollet. Really cool zydeco, country, rock—really diverse. My friend C.C. Adcock, who lives in Lafayette, just produced an album by a fellow, a staple down there called Tommy McLain. That's coming out in England, and I believe that Nick Lowe co-wrote a few things with Tommy, and Elvis Costello. They really love him. He's A1. I was really taken with that record.

I was also listening to some Donna the Buffalo stuff. Some Grateful Dead. Listening to some of their catalog always feels good. And a bluegrass group called High Fidelity that's got a new album. They're really, really terrific. You know, there's some good stuff out there.

That's encouraging to hear. Some people of a certain generation say, "There's been no good music since 1971."

Oh no, no. Gosh. There's plenty of stuff. Working on this radio show with Buddy Miller, the Buddy & Jim Show—outlaw country—Buddy keeps me on my toes. We need to make playlists occasionally, so I need to bring him things. Then, I'm discovering new things through him. He has a real encyclopedic musical mind. So, that's always good.

Back in the day—we're on hiatus now—but there was this show that I was working with called Music City Roots in Nashville. Usually, we had four different bands per night. We did that once a week. It's on some PBS TV station and it's a syndicated radio show, too. It's been great to hear new stuff—new artists, or even veteran artists that have new material.

There is no shortage of great music out there, new stuff. Constantly.

And the old guard is still great. People were calling Bob Dylan, Paul McCartney and the Rolling Stones old guys when I was a kid, but they remain potent forces today.

That's so good. I feel like over the last few years, too, I feel like I'm writing more than I ever have, really. At first, during this pandemic, I didn't want to do everything. That did slow me down for several months, but then I started writing again.

Read More: GRAMMY Rewind: Watch Bob Dylan Accept His GRAMMY Lifetime Achievement Award In 1991

What was the catalyst for that?

Well, it was such a depression and this uncertainty of tragedy going on all the time. I think it was when I started thinking in terms of grabbing some songs that didn't seem to fit on a country record I was working on. I was kind of recording whatever came out. Some of these songs weren't country. Then, I wanted to get something out there to help soothe people.

So, that kind of got me back on track writing again, because I realized I had some stuff that really spoke to the time we were going through—some of these non-country songs. Some new things just started coming out then. You know, it's interesting. I feel like a lot of times, I need the structure of a concept—of some kind of album—to get me going. Because that's one of my favorite things to do—to make records.

At the same time, sometimes it can be really daunting because I'll have very little or no material prepared when I go into the studio. As the studio date gets closer and closer, something comes out, either the day before or that morning. It's not always like that, and especially if I co-write with somebody, then that can be more random.

But that helped me start writing again: When I said, "Hey, I want to get something out there to people."

Tell me about your relationship with Robert Hunter. When I think of him, I think of how strong Grateful Dead tunes are at their core, partly thanks to him.

When I first started listening to the Grateful Dead, American Beauty and Workingman's Dead were my entry port for them. I was a junior in high school in North Carolina. There was this thread, musically—because I'd been loving country and rock and bluegrass—and they were so different-sounding, but synthesizing all these different styles in a way I hadn't heard.

And lyrically—of course Dylan had done some amazing things, and had his way—but it was just so different. I felt like Robert Hunter was touching on something that was in the back of my consciousness and subconsciousness. There was something in his descriptions of things I was thinking or feeling but couldn't put into words myself. Just kind of evoking different things I felt.

Some of the lyrics were about death and things like this, that you would hear in older bluegrass songs or folk music or whatnot. But you weren't hearing about those in a rock band. That marriage of Robert's lyrics and Jerry Garcia's [music] and other members of the band he co-wrote with, there was this perfection about it to me.

Let's talk about Hope, which exudes a sense of help, gentility and care. The worst thing about this era, to me, is how we treat each other.

It's funny: When you go to a movie, depending on the type of movie, when you get up out of your seat and you're walking up the aisle, whether you're watching some superhero [movie] or you walk away feeling scared or sad or whatnot—you either feel like you want to have an altered state of consciousness after you hear a song, or you want to party, or you feel angry. All these various things.

I think things have been so horrible that I figured it can't hurt to just have some good songs that make you want to get through. You want to get through these times and you want to help other people get through these times. There's some release, some kind of relief, a little bit, because we all need that.

Not that this record is some kind of a cure-all or anything like that, but I enjoy hearing something that makes me feel good, and I hope that's what this record will do.

Well, you don't even need to qualify it as not being a cure-all. It's a personal expression and artistic offering, not a product.

Yeah, absolutely. It's not an answer or anything like that.

The reason I decided to call it Hope: There's a song on there called "Here's to Hoping." [Perhaps] even if people don't listen to the record—even if they just see this beautiful painting that Robert Hunter's wife, Maureen, did as the cover, and see the word "Hope"—that it will trigger something and release some hope. We all need that, no matter who we are and what's going on.

This is as bleak as things have been for many of us in life. Some of us have seen worse, and much harder and more terrible times, but for a lot of us, this period has been pretty bad.

Jim Lauderdale. Photo: Scott Simontacchi

One of the worst parts is this sense of fetishizing the worst possible outcome. Optimism feels like a rebellion these days.

Definitely. It brought out the worst and the best of each one of us, in some way or another, during whatever time you were in—whatever phase of this you were going through. There were many phases for a lot of us. Reading about certain people who survived certain situations that were so dire, what many of the survivors said was, "How I got through was with hope. I didn't give up hope."

Sometimes, that really does seem impossible. Hope almost seems laughable, but we just have to have it. To keep going.

What else can you tell me about the essence of the record?

Let me see. Let me grab it here. [Pauses.] Well, these songs just really seem to fit together with this theme. I co-produced it with Jay Weaver, who's the bass player. He didn't do the last bluegrass album I did, but there were two other studio albums on Yep Roc that he co-produced with me.

We used this kind of crew of guys [that typically work together], with the exception of one or two guys. I just really feel like all these musicians played so great. It's just such a joy to work with them. So, it's nice to have that camaraderie. It's like a band. That was really uplifting for me to do all this stuff with these guys.

To wrap up the thing about Robert Hunter: We started working together, I believe it was in 1996, when I was going to do my first record with Ralph Stanley. That's how it started, and then he came to Nashville for a little while. We just hit it off, writing-wise. I'd go out there sometimes to California. Sometimes, I'd send him melodies or he'd send me lyrics.

I had recorded about six albums of just our collaborations, and then there were various tracks on other solo albums of mine. So, we recorded about 88 things that we wrote. We've written about 100 songs, and some of these haven't been released.

"Memory" was the last thing he heard that we wrote, and so I'm really glad he got to hear it. I really miss him very much and feel his presence every day and think about him every day. He's a big part of my musical life, and he was a wonderful guy. I think he was the most interesting and intelligent guy I ever met.

Photo: Nick Spanos

interview

Living Legends: How Dead & Company Drummer Mickey Hart Makes Visual Art From Vibrations — And Brought It To Las Vegas' Sphere

Dead & Company are currently embarking a residency at Las Vegas' sphere, which features drummer Mickey Hart's eye-popping, unconventional art. Hart spoke to GRAMMY.com about how it came to be, and how the Grateful Dead's legacy continues to ripple forth.

Living Legends is a series that spotlights icons in music who are still going strong today. This week, we interviewed Mickey Hart, one of two drummers — along with Bill Kreutzmann — of the Grateful Dead and its contemporary offshoot, Dead & Company.

His first-ever solo art exhibition, Art at the Edge of Magic, will run through July 13 at the Venetian Resort in Las Vegas, as part of the Dead Forever Experience. His work is also incorporated into their current residency at Las Vegas' Sphere.

After decades behind a drum kit with the Grateful Dead, and now in the same role in Dead & Company, Mickey Hart has learned a truly cosmic lesson: "The basis of all of creation is vibratory."

For years, in parallel with his legacy as a music maker, he's made visual art using a sui generis method, which has plenty in common with his techniques as a drummer. Check out his visual art, which he's been creating for years in parallel with his music making; some of it may look like paintings, but that doesn't quite describe what it is.

Rather, Hart employs vibrations — much like he's done behind the kit for decades — to bring out hitherto-invisible dimensions in paint. The results are captivating to the eye — at times, otherworldly.

The strength of Hart's visual art has added another layer to the Grateful Dead cosmos. If you're in or near Las Vegas, you can check out these works as part of the Dead Forever Experience, in an exhibition at the Venetian running until mid-July.

Additionally, if you catch Dead & Company during their Sphere residency (which runs through July 13), you can immerse yourself in it during the famous "Drums/Space" portion of the set — a percussive, celestial section stretching way back in Dead setlist history.

"I just love to do it. Sometimes, your hobbies overtake you and become a necessary ingredient in your life," Hart cheerily tells GRAMMY.com. "And that's what happened with this visual medium, that it kind of grew on me and made me want to go back over and over and over again to learn the craft."

Whether or not you'll be heading to Vegas, read on for an interview with Hart about how he makes these sumptuous textures and hues truly pop — as well as his gratitude for the potency and longevity of the Dead's afterlife. (No pun intended.)

This interview has been edited for clarity.

Your visual work is beautiful. What can you tell readers about how you make it — the brass tacks?

Well, I wouldn't say I paint. I don't use brushes — sometimes, once in a while — but really it's more of a pouring medium, and a spinning medium, and so forth. But I use vibrations in the painting process, and I think that's why people call it vibrational expressionism.

I use a subwoofer and the Pythagorean monochord — a stringed instrument — drives the subwoofer. Pythagoras, of course, invented it, and it goes down very low to 15 cycles, sometimes 10 cycles. And that vibrates the paint. I mix multiple colors, and the colors come up within each other, and it reveals these details that you cannot get in any other way.

And I just kind of fell on it. In the beginning, I was drumming them — beating underneath them and so forth. But now, I've progressed to using a Meyer subwoofer, and it works just fine. And that's how the paintings are born. They're vibrated into existence.

Once I apply my mumbo jumbo to it, and using additives that create unique features — shapes, people, animals, mountain ranges, glaciers — you see all kinds of things within the paintings if you look at them, and let yourself go, and become part of the paintings.

Everybody has their own interpretation of [what they reveal], which is really important. These are not, like, a rose, or a vase, or a car. It's not that kind of art form. So, it raises your consciousness. And if you can connect with it, you get high. And that's what these things are all about. That's what art's all about. No matter what it is, audio or visual, it's consciousness raising at its best.

I take it you've been developing this ability in parallel with your work in the Dead universe for some time.

Well, of course. I work with vibrations. The vibratory world is where I live, and I make my art there. It's always been like that. I'm a lover of low end; low frequencies are my specialty. And because I'm a percussionist and many of my drums are very large and they speak to the range, the frequency, which is not normally accessed.

So, I create these works using these low-frequency creations. And that was something that I fell on years ago, but as a hobby; this was nothing more than an escape to another virtual headspace. Now, I share it with others.

I feel like this sound-based approach to visual art is a fairly unexplored space.

For sure. I mean, you can look it up. I've looked it up. And when you look up vibrational expressionism, I'm the only one that's there. Someone coined that term years ago, and it's kind of fitting.

I might be unique in that particular way, but that's the only way I know how to bring the colors up within themselves and reveal the super details.

Photo: Emily Frost

And I'm sure this process is fluid and mutable; you don't apply the same technique for every piece.

Yes, I apply different frequencies and different rhythms to different paintings. They're not the same. Every time I approach it — whether it be a canvas, or wood, or plexiglass, or glass, or whatever the surface is — it's always different. I never repeat. Every one of them is unique.

It's about the mixing of the paints, and the ingredients I put in the paint. And then you have to let it go and you jam. That's what these works are — they're jams. Sometimes, I have a thought on how I want it to be, and then sometimes it'll completely change once I put paint to canvas.

You learn over years. I've been doing this for about 25 years as a hobby, so I've got hundreds of these. And some of them never see the light of day. That's the luck of the draw, but luck favors the prepared mind, and I prepare that before I go in. I focus and concentrate on not concentrating. I just try to be there now and let the flow happen.

I improvise. That's my love. That's the only thing I really know how to do. Memorizing things and repeating is not who I am. I don't paint by the numbers. You don't need me for that.

Much like what you do on stage!

The Grateful Dead never did memorize many things. It was mostly a seat-of-the-pants kind of art form, but you learn how to become a seat-of-the-pants artist, if you will. There's adventure, there's failure, there's success, there's luck, there's chaos, there's order, and back and forth.

The duality of all of that reflects life. It gets you high too. You can look at it and all of a sudden you're in a different, virtual space. That's what art does — good art, anyway. It puts you in a place of great wonder and awe.

Photo: Emily Frost

Can you talk about using the Sphere as a canvas for your work?

That's how I look at it — as a blank canvas. When I hit the stage, I'm not thinking of anything. I prepared, I have my skill, I'm ready to go, but I'm not really thinking in the normal sense of the word. I throw that away and I just feel muscle memory, you might call it.

When you're playing music in a band, you become a groupist. You learn to be able to interrelate between six people each having their own consciousness, making something larger than the parts. Music is great at that. But in painting, it's a singular thing.

Music is just the moving of air. That's the delivery system. It's the movement of air. And in this case, it's light. It's what the light does to you. The eye is more powerful than the ear as an organ. So people really react to the visual. Hopefully in the Sphere, there's a combination of both that come together and form something much larger.

I appreciate that you view a drum as far more than simply a drum.

It's not something that just played to keep time. It's something that is an integral part of the orchestra, right up there with melody and harmony. The primacy of rhythm is something that has come into music in this century. If you listen to the radio, it's rhythmic-driven, mostly. Of course, there's the melodies, but the basis of it all is rhythmic.

Visual art is the same thing. It's all about rhythm and flow. If you don't have that, you don't really have anything. You have to have a groove.

The basis of all of creation is vibratory. These arts are just miniatures of what's happening in the cosmos. I mean, we are in the wash of these vibrations that were created 13.8 billion years ago from the singularity, the big bang, and that's still washing over us. And that's where art comes in. It connects you to the infinite universe at its best.

You guys seemed to realize early on that you could transcend simply playing rock songs in a band.

When we were younger, we were all ingesting psychoactive drugs. They certainly freed our perspective, and created a different kind of perspective when we all played together. Some of it was drug-related, you might say. We took what we could from those experiences and created a new kind of music.

That was an important part of our exploratory nature as we were falling on Grateful Dead music. We were exploring realms of consciousness that were not accessible to us normally in a normal waking state. These chemicals certainly helped in that respect, used correctly and professionally. They were an enormous, enormous help.

And now we're finding out that LSD is being used in therapeutic and medicinal and diagnostics and all of that. These are very helpful in many ways.

Photo: Emily Frost

How has it felt watching the Grateful Dead turn into a franchise, a universe? This visual element at the Sphere adds a whole new layer to it.

Well, it's very interesting to see all the corners and of the universe that the Grateful Dead spirit has reached and all the people and all the bands that copy our music. It's very rewarding and complimentary, I think.

We knew it was special. First time I ever heard it, I knew it was special. How special? You never know, but you have to keep at it being special. And eventually, it skips generations, which is what we've done — generation, after generation, after generation. The parents share with their kids, their kids, their kids.

It's something that's very friendly — hanging out with your parents at a concert like that, and having a great time together, and sharing something that they shared when they were younger.

It's fantastic. It's unbelievable that it has that power. I was just talking to someone the other night and they asked me to explain it. You can't explain it in words. You have to hear it. You have to be there. You have to feel it. You have to feel the community that it spawns, and this feeling that you get in the music. It's very seductive, if you allow yourself that moment.

I was just reading this morning that Diplo — the electronic musician, a very good musician — just became a Deadhead the other night.

Really!

Oh, yeah. It transformed him completely. You never can tell who gets touched by our music. It's something that's not explainable, but it keeps going on. The people will not let it go.

As long as people are interested in our kind of music and our kind of scene, we'll keep playing. There's no end to it until we don't have the facility to play, or the rhythm stops. I plan to do this till the day I die. There's no question about it. I've always thought that. There's no secret.

I think Bob and I both agree on that, and all of the Grateful Dead, Bill, Phil, certainly Jerry, we're all in the same boat when it comes to Grateful Dead music, the passion that we bring to it. And it's very rewarding that people enjoy it as deeply as they do.

I tell you, I can't express the gratitude that I have just being part of it. We all feel that same way. It's very humbling, to be honest with you, that it's grown to be this. It was just a little cub. Now it's a roaring lion. It's just a gigantic monster that is always meant for the good, and that's very rewarding. It's a good life to lead. We work very hard at it.

A Beginner's Guide To The Grateful Dead: 5 Ways To Get Into The Legendary Jam Band

Photo: Jeff Kravitz/FilmMagic

video

GRAMMY Rewind: Kendrick Lamar Honors Hip-Hop's Greats While Accepting Best Rap Album GRAMMY For 'To Pimp a Butterfly' In 2016

Upon winning the GRAMMY for Best Rap Album for 'To Pimp a Butterfly,' Kendrick Lamar thanked those that helped him get to the stage, and the artists that blazed the trail for him.

Updated Friday Oct. 13, 2023 to include info about Kendrick Lamar's most recent GRAMMY wins, as of the 2023 GRAMMYs.

A GRAMMY veteran these days, Kendrick Lamar has won 17 GRAMMYs and has received 47 GRAMMY nominations overall. A sizable chunk of his trophies came from the 58th annual GRAMMY Awards in 2016, when he walked away with five — including his first-ever win in the Best Rap Album category.

This installment of GRAMMY Rewind turns back the clock to 2016, revisiting Lamar's acceptance speech upon winning Best Rap Album for To Pimp A Butterfly. Though Lamar was alone on stage, he made it clear that he wouldn't be at the top of his game without the help of a broad support system.

"First off, all glory to God, that's for sure," he said, kicking off a speech that went on to thank his parents, who he described as his "those who gave me the responsibility of knowing, of accepting the good with the bad."

Looking for more GRAMMYs news? The 2024 GRAMMY nominations are here!

He also extended his love and gratitude to his fiancée, Whitney Alford, and shouted out his Top Dawg Entertainment labelmates. Lamar specifically praised Top Dawg's CEO, Anthony Tiffith, for finding and developing raw talent that might not otherwise get the chance to pursue their musical dreams.

"We'd never forget that: Taking these kids out of the projects, out of Compton, and putting them right here on this stage, to be the best that they can be," Lamar — a Compton native himself — continued, leading into an impassioned conclusion spotlighting some of the cornerstone rap albums that came before To Pimp a Butterfly.

"Hip-hop. Ice Cube. This is for hip-hop," he said. "This is for Snoop Dogg, Doggystyle. This is for Illmatic, this is for Nas. We will live forever. Believe that."

To Pimp a Butterfly singles "Alright" and "These Walls" earned Lamar three more GRAMMYs that night, the former winning Best Rap Performance and Best Rap Song and the latter taking Best Rap/Sung Collaboration (the song features Bilal, Anna Wise and Thundercat). He also won Best Music Video for the remix of Taylor Swift's "Bad Blood."

Lamar has since won Best Rap Album two more times, taking home the golden gramophone in 2018 for his blockbuster LP DAMN., and in 2023 for his bold fifth album, Mr. Morale & the Big Steppers.

Watch Lamar's full acceptance speech above, and check back at GRAMMY.com every Friday for more GRAMMY Rewind episodes.

10 Essential Facts To Know About GRAMMY-Winning Rapper J. Cole

Photo: Roger Ressmeyer/CORBIS/VCG via Getty Images

feature

A Beginner’s Guide To The Grateful Dead: 5 Ways To Get Into The Legendary Jam Band

Not a Deadhead? Dread not; GRAMMY.com offers a few suggested routes to begin your long strange trip with the Grateful Dead.

Just because you never traded bootleg tapes with strangers or dropped acid to experience that Timothy Leary whacked-out feeling, you can still appreciate the Grateful Dead.

When the Dead began their psychedelic trip back in the late 1960s, the media categorized their followers as lazy, counter-culture drop-outs. The reality: these devotees, known today as Deadheads, were just music-lovers that shared values and believed in the power of community, peace and love. Today, Deadhead culture and the band’s popularity is as relevant as ever. Even as the original fans age, new Gen Z disciples arrive each year to carry on the jams.

Flash back to San Francisco, 1965. The original lineup, calling themselves the Warlocks, formed from the remnants of Palo Alto band Mother McCree’s Uptown Jug Champions and Bay Area folk group the Wildwood Boys. After learning of another group called the Warlocks, the band became the Grateful Dead overnight. The story goes that guitarist/vocalist Jerry Garcia picked the band’s name randomly from the dictionary.

The earliest gigs under this new moniker occurred at Ken Kesey’s infamous Acid Test parties. Founding members were: Garcia; Bob Weir (rhythm guitar/vocals); Ron "Pigpen" McKernan (harmonica, keyboards/vocals); Phil Lesh (bass) and Bill Kreutzmann on drums. Robert Hunter and Mickey Hart joined the group in 1967.

The Grateful Dead were a free-flowing fusion of folk, rock, soul, blues and jazz, and their improvisational approach to the music created a new classification in the lexicon: a "jam band." A Dead concert was all about the songs, the feelings, and the interplay between musicians. The jams mattered, not perfection.

Playing live was where the Grateful Dead made their money (they were one of the top grossing touring acts for decades), playing some 2,200 plus concerts globally in its 30-year career. Deadheads recorded these shows, traded tapes, and followed the white line in VW vans from town to town to take communion with the group night after night. No two shows were the same. Songs meandered longer or shorter depending on where the music — and the Deadheads — led them on any given evening.

When Jerry Garcia died on Aug. 9, 1995, the remaining members said without their charismatic leader, the Grateful Dead (at least in name) was dead. However, the spirit of the band has carried on with the various solo projects, the Dead & Company (featuring some of the original band members) and countless jam bands.

The Dead defined an era. The band represented a subculture that influenced the mainstream for decades from lifestyle to fashion; from music to marketing. More than 50 years since the Grateful Dead started jamming, Deadheads are still grateful for the music.

How do you get into — but also get — the Grateful Dead? There is no one way. Like all music, to quote the prophet Robert "Nesta" Marley: "when it hits you feel no pain." The important thing with the Dead’s music is that you feel something.

With the release next month of a deluxe expanded and remastered version of Wake of the Flood (the band’s 1973 debut on Grateful Dead Records), here’s a primer on how to get into these merrymakers, who received a GRAMMY Lifetime Achievement Award in 2007. Start that long strange trip with these five ways to appreciate — and get to know — the Grateful Dead.

Start With The Classics

Released just five months apart in 1970 Workingman’s Dead and American Beauty are the touchstones. This pair of albums represented a shift for the band from its psychedelic roots to an Americana road of devotion; the influence of the Bakersfield sound is all over these songs. Do a deep listen of these records and hear some of the Dead’s best-loved classics and Dead show setlist staples for decades. Discover the beauty of the music, the complexity of the arrangements and the heartfelt harmony.

Workingman’s Dead, released in June 1970, opens with "Uncle John’s Band" — one of the band’s most well-known songs and most oft-covered — it was also the band’s first chart hit. Among the rest of the eight songs here, "Casey Jones," about a train engineer speeding down the tracks "high on cocaine," is another classic.

American Beauty, the band’s fifth studio record, showcased the Dead at their creative heights and has gone on to double-platinum certification Arriving Nov. 1, 1970, the album is an Americana masterpiece that features acoustically-inclined country-rock numbers mixed with toe-tapping, groovy psychedelic jams.

Put on your headphones to truly savor the 10 songs that include live regulars: "Friend of the Devil," "Truckin,’" "Box of Rain," "Sugar Magnolia" and "Ripple."

Jam On: Appreciate & Listen To The Followers

The Allman Brothers Band are a close cousin of the Grateful Dead; they also loved to jam and fuse genres. In the 1980s and 1990s many other bands became Dead disciples, among them Phish, Widespread Panic, Blues Traveler, the Dave Matthews Band, Government Mule and the String Cheese Incident.

These groups continue the jam band tradition for new generations. This in-the-moment, letting the music go where it was meant to go, is their guidepost. The jam band spirit is evident in this 11-minute live version of the Allman Brothers' "Whipping Post" recorded at the Fillmore East in 1973.

And, let’s not forget those Vermont boys Phish, who showcased their ability to jam with the best of the best during a string of 13 concerts, from July 21 to August 6, 2017 at Madison Square Garden (MSG), dubbed The Baker’s Dozen. Each night of the residency — which has continued, with slightly fewer dates, for years — featured a different set list with no songs repeated throughout this residency at MSG. Night four included a 29-minute jam of their song "Lawn Boy."

Keep On Truckin’: Follow The Long & Winding Road To Uncover More Dead Songs

The Grateful Dead released 13 studio albums and 77 live records. Their archives are vast and deep, and new live recordings are being released every year. The joy of getting into the Grateful Dead is that there is no rulebook. Just as their shows had no set structure, becoming a Dead fan has no defined musts. That said, here are another trio of songs you must listen to to better understand and appreciate this band.

"Friend of the Devil"

The second song from American Beauty, this acoustic number is a quintessential Dead track.

"Franklin’s Tower"

First released in 1975 on Blues for Allah, this rollicking number with its repetitive chorus telling you to "roll away the dew," is one of the Dead’s most catchy numbers. Just listen to the live version on Dead Set and try to disagree.

"Touch of Grey"

The Grateful Dead got another mainstream bump in the late '80s thanks to MTV. The video (the first ever official one made by the Dead) for this single from the 1987 album In the Dark, featured the band turned into life-size marionette skeletons playing this song live. The memorable refrain: "I will get by/ I will survive," and heavy rotation on TV, helped this song become a Top 10 Billboard hit (the group’s only Top 40 charting song of its 30-year-career), bringing the Dead’s music to a new generation.

Get Turned On & Tune Out

After listening to some of the Dead’s best live records like Europe ‘72 and Dead Set (1981), subscribe to the Grateful Dead’s YouTube channel. Make sure you’ve got time on your side; for if you go down this rabbit hole, there is no telling when you might resurface.

That's not a bad thing. Get a taste of what it was like to attend a Dead show. Watch a Dead concert from different decades like this show at the famed San Francisco Winterland on New Year’s Eve in 1978, this one from California’s Shoreline Amphitheatre in 1987, or this one from 1990 at Three RIvers Stadium in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Read On! The Dead Are Far From Dead

Thousands of scholarly theses have been written — and continue to be published — on the band; college courses have been created and even a journal is devoted to discussing the cultural significance of the Grateful Dead. Marketing gurus have shared business lessons learned from the band such as the innovative ways they sold and promoted their music. Head to your local library or independent bookstore and ask what books they have on the Grateful Dead.

A quick Google search reveals dozens upon dozens devoted to this American band: from memoirs written by Dead members Mickey Hart and Phil Lesh, to academic explorations and longform odes by Deadheads. Ready to dive deeper? This film offers an in-depth look at Deadheads’ devotion and gives a behind-the-scenes glimpse of the connection between a fanbase and a band. And learn more here than you ever thought you wanted — or needed — to know about the Grateful Dead. What a long, strange trip it’s been.

No Accreditation? No Problem! 10 Potential Routes To Get Into Jazz As A Beginner

Photo: Rachel Kupfer

list

A Guide To Modern Funk For The Dance Floor: L'Imperatrice, Shiro Schwarz, Franc Moody, Say She She & Moniquea

James Brown changed the sound of popular music when he found the power of the one and unleashed the funk with "Papa's Got a Brand New Bag." Today, funk lives on in many forms, including these exciting bands from across the world.

It's rare that a genre can be traced back to a single artist or group, but for funk, that was James Brown. The Godfather of Soul coined the phrase and style of playing known as "on the one," where the first downbeat is emphasized, instead of the typical second and fourth beats in pop, soul and other styles. As David Cheal eloquently explains, playing on the one "left space for phrases and riffs, often syncopated around the beat, creating an intricate, interlocking grid which could go on and on." You know a funky bassline when you hear it; its fat chords beg your body to get up and groove.

Brown's 1965 classic, "Papa's Got a Brand New Bag," became one of the first funk hits, and has been endlessly sampled and covered over the years, along with his other groovy tracks. Of course, many other funk acts followed in the '60s, and the genre thrived in the '70s and '80s as the disco craze came and went, and the originators of hip-hop and house music created new music from funk and disco's strong, flexible bones built for dancing.

Legendary funk bassist Bootsy Collins learned the power of the one from playing in Brown's band, and brought it to George Clinton, who created P-funk, an expansive, Afrofuturistic, psychedelic exploration of funk with his various bands and projects, including Parliament-Funkadelic. Both Collins and Clinton remain active and funkin', and have offered their timeless grooves to collabs with younger artists, including Kali Uchis, Silk Sonic, and Omar Apollo; and Kendrick Lamar, Flying Lotus, and Thundercat, respectively.

In the 1980s, electro-funk was born when artists like Afrika Bambaataa, Man Parrish, and Egyptian Lover began making futuristic beats with the Roland TR-808 drum machine — often with robotic vocals distorted through a talk box. A key distinguishing factor of electro-funk is a de-emphasis on vocals, with more phrases than choruses and verses. The sound influenced contemporaneous hip-hop, funk and electronica, along with acts around the globe, while current acts like Chromeo, DJ Stingray, and even Egyptian Lover himself keep electro-funk alive and well.

Today, funk lives in many places, with its heavy bass and syncopated grooves finding way into many nooks and crannies of music. There's nu-disco and boogie funk, nodding back to disco bands with soaring vocals and dance floor-designed instrumentation. G-funk continues to influence Los Angeles hip-hop, with innovative artists like Dam-Funk and Channel Tres bringing the funk and G-funk, into electro territory. Funk and disco-centered '70s revival is definitely having a moment, with acts like Ghost Funk Orchestra and Parcels, while its sparkly sprinklings can be heard in pop from Dua Lipa, Doja Cat, and, in full "Soul Train" character, Silk Sonic. There are also acts making dreamy, atmospheric music with a solid dose of funk, such as Khruangbin’s global sonic collage.

There are many bands that play heavily with funk, creating lush grooves designed to get you moving. Read on for a taste of five current modern funk and nu-disco artists making band-led uptempo funk built for the dance floor. Be sure to press play on the Spotify playlist above, and check out GRAMMY.com's playlist on Apple Music, Amazon Music and Pandora.

Say She She

Aptly self-described as "discodelic soul," Brooklyn-based seven-piece Say She She make dreamy, operatic funk, led by singer-songwriters Nya Gazelle Brown, Piya Malik and Sabrina Mileo Cunningham. Their '70s girl group-inspired vocal harmonies echo, sooth and enchant as they cover poignant topics with feminist flair.

While they’ve been active in the New York scene for a few years, they’ve gained wider acclaim for the irresistible music they began releasing this year, including their debut album, Prism. Their 2022 debut single "Forget Me Not" is an ode to ground-breaking New York art collective Guerilla Girls, and "Norma" is their protest anthem in response to the news that Roe vs. Wade could be (and was) overturned. The band name is a nod to funk legend Nile Rodgers, from the "Le freak, c'est chi" exclamation in Chic's legendary tune "Le Freak."

Moniquea

Moniquea's unique voice oozes confidence, yet invites you in to dance with her to the super funky boogie rhythms. The Pasadena, California artist was raised on funk music; her mom was in a cover band that would play classics like Aretha Franklin’s "Get It Right" and Gladys Knight’s "Love Overboard." Moniquea released her first boogie funk track at 20 and, in 2011, met local producer XL Middelton — a bonafide purveyor of funk. She's been a star artist on his MoFunk Records ever since, and they've collabed on countless tracks, channeling West Coast energy with a heavy dose of G-funk, sunny lyrics and upbeat, roller disco-ready rhythms.

Her latest release is an upbeat nod to classic West Coast funk, produced by Middleton, and follows her February 2022 groovy, collab-filled album, On Repeat.

Shiro Schwarz

Shiro Schwarz is a Mexico City-based duo, consisting of Pammela Rojas and Rafael Marfil, who helped establish a modern funk scene in the richly creative Mexican metropolis. On "Electrify" — originally released in 2016 on Fat Beats Records and reissued in 2021 by MoFunk — Shiro Schwarz's vocals playfully contrast each other, floating over an insistent, upbeat bassline and an '80s throwback electro-funk rhythm with synth flourishes.

Their music manages to be both nostalgic and futuristic — and impossible to sit still to. 2021 single "Be Kind" is sweet, mellow and groovy, perfect chic lounge funk. Shiro Schwarz’s latest track, the joyfully nostalgic "Hey DJ," is a collab with funkstress Saucy Lady and U-Key.

L'Impératrice

L'Impératrice (the empress in French) are a six-piece Parisian group serving an infectiously joyful blend of French pop, nu-disco, funk and psychedelia. Flore Benguigui's vocals are light and dreamy, yet commanding of your attention, while lyrics have a feminist touch.

During their energetic live sets, L'Impératrice members Charles de Boisseguin and Hagni Gwon (keys), David Gaugué (bass), Achille Trocellier (guitar), and Tom Daveau (drums) deliver extended instrumental jam sessions to expand and connect their music. Gaugué emphasizes the thick funky bass, and Benguigui jumps around the stage while sounding like an angel. L’Impératrice’s latest album, 2021’s Tako Tsubo, is a sunny, playful French disco journey.

Franc Moody

Franc Moody's bio fittingly describes their music as "a soul funk and cosmic disco sound." The London outfit was birthed by friends Ned Franc and Jon Moody in the early 2010s, when they were living together and throwing parties in North London's warehouse scene. In 2017, the group grew to six members, including singer and multi-instrumentalist Amber-Simone.

Their music feels at home with other electro-pop bands like fellow Londoners Jungle and Aussie act Parcels. While much of it is upbeat and euphoric, Franc Moody also dips into the more chilled, dreamy realm, such as the vibey, sultry title track from their recently released Into the Ether.