Photo: Kevin Carter

list

Why Dead & Company's Sphere Residency Is The Ultimate Trip

The 30-date Las Vegas residency is an unprecedented look at Dead & Co's live artistry. With stunning visuals and immersive technology, the Dead Forever residency takes attendees on an unpredictable, eye-popping vortex journey.

The scene on Saturday, July 13, was one mostly familiar to Dead & Company fans: Usual suspects Jeff Chimenti on keys, Oteil Burbridge on bass, Mickey Hart on drums, and John Mayer on guitar, a Silver Sky in hand. Grateful Dead co-founder Bob Weir dutifully approached the microphone to deliver one of the Dead’s best-known opening lyrics: "You tell me this town ain’t got no heart."

Throughout the evening, appreciative cheers and whistles sounded at the first notes of a classic, like this one, intermingling with the hints of marijuana in the air. The crowd of thousands, who’d traveled from both near and far for the occasion, swayed to the music. Largely clad in the tie-dye t-shirts customary to the Dead fandom, they comprised a vivid sea of color, visible even in the venue’s dimmest lighting.

Bathed in the glow of a key anomaly — a 160,000-square-foot curved LED canvas — a Deadhead sitting in the row ahead of me turns around and asks if I’m enjoying the show (I am). When I return the question, he is emphatic, his response succinct: "it’s transformative."

He’s not wrong in that the audiovisual spectacle — which wrapped its eighth of 10 weeks this past weekend — metamorphoses Dead & Company’s concert format. Since it debuted in May, the now 30-date Las Vegas residency, dubbed Dead Forever, has attracted old-school and new-generation Deadheads, as well as curious first-timers. From one-of-a-kind production tools, like its 16K LED display (the highest-resolution display in the world, per developers) and stereographic projection, Sphere has empowered Dead & Company to carry forth the legacy of one of the most fervently-loved bands in American music history, with unprecedented storytelling capacities and complete creative control.

Read on for four reasons why Dead & Company’s residency at Las Vegas’ most-talked-about venue is the rock outfit like they’ve never been seen before.

The Meeting Of Music & Visuals Allows For True Narration

For the nearly four hours that Dead & Company play each Thursday, Friday, and Saturday of a residency week, the domed venue adjacent to the Venetian transforms from Sphere to spaceship. Narratively, the show is stylized as a long, strange trip through space that issues nods to the Grateful Dead’s history.

It’s only fitting that this story begins in San Francisco, where the Dead’s townhouse in the heart of the Haight-Ashbury district becomes the focal point of the audiovisual journey’s intro. The 360-degree view of the Dead’s residence and the larger row of townhouses to which it belongs pans to a drone shot of the Bay Area at golden hour and soon thereafter, outer space.

Visually, attendees travel through time and space in an unpredictable, eye-popping vortex of fantasticality (and sometimes, reality). Take, for example, the segment that recreates the Dead’s performance at the Great Pyramid in Giza, Egypt. The scene is punctuated by black bats that flap swiftly through the desert landscape — a detail that comes as a surprise to those in the audience, and one ultimately added based on Weir’s recollection of this very phenomenon during the 1978 event, Mayer tells GQ.

Before Dead & Company bring Dead Forever full-circle by returning to 710 Ashbury Street at the show’s close, the show winds through a colorful, circuitous run of visuals: the Dead’s iconic technicolor dancing bears, Cornell University’s Barton Hall, and a wall made entirely of digital reproductions of Dead event posters and hard tickets. The show’s depth of reference is plunging, and Sphere’s technology allows the story to play like an abstract movie that blurs timelines, affording Dead & Company an unusual and nonpareil opportunity to leverage live storytelling in a way they’ve never before been able to.

While Dead Forever is accessible purely as a visual marvel, for the initiated, it is rife with Easter eggs. Its historical allusions are familiar touch points for the Deadheads who hopped on the metaphorical bandwagon back when Jerry Garcia was at its helm. Although some of its segments will evade those less fluent in the Dead’s storied past, they can nevertheless serve as educational gateways to it (and to greater, deeper fandom) for those who leave the show wanting to learn more.

Read more: A Beginner’s Guide To The Grateful Dead: 5 Ways To Get Into The Legendary Jam Band

In A Way, Everything Is New

Whether one has seen Dead & Company once, five times, 20 times, or never before matters not, for Dead Forever is a brand-new show. Familiarity with the Grateful Dead’s legacy and its contemporary offshoot's genesis certainly enriches the overall experience, but it’s not a requisite to enjoy the show, making the residency a particularly good entry point for the Dead & Company-curious who may have missed them on The Final Tour in 2023.

Dead Forever levels the playing field for attendees in that, apart from the songs on the setlist, the residency represents net-new material. The marriage of music and visuals makes each of the 18 tunes new from the standpoint of an audiovisual experience, and the novelty of Dead Forever deepens for even the most experienced Deadhead.

"When I was growing up, ‘Drums’ was always my bathroom song, but now you don’t want to miss it," an attendee tells GRAMMY.com at the end of the first set (Dead & Company play one six- or seven-song set and take a 30-minute intermission before beginning the evening’s second and final set).

A customary part of the Dead’s sets, "Drums/Space" is an extended percussion segment that takes on new life in Dead Forever. Led by Mickey Hart, the set two standout is where sound evolves into physical feeling. As this portion of the show starts, the curved LED canvas swirls with images of different drums that move wildly as Hart and Jay Lane (who stands in for Grateful Dead co-founding member, Bill Kreutzmann) diligently drum, steadily increasing the pace and intensity with which they do so. The instruments that grace Sphere’s screen are Hart’s own, the drummer tells Variety. Following 3D-photographing that enables them to be displayed in this fashion, an ensemble of at least 10 different drums joins the visual jamboree.

The cinematic, multisensory nature of this segment grows increasingly climactic, with the percussion becoming so thunderous it becomes physical. No surprise, considering Sphere’s immersive, crystal-clear sound system, or the fact that 10,000 of the venue’s 17,385 seats are haptic seats that can vibrate in time with the mounting percussion. This technology transforms "Drums/Space" and allows a customary piece of the Dead’s traditional sets to be heard, seen, and felt anew.

The Environment Is Unusually Immersive —And Intimate

Upon mention of Sphere’s size — the globe measures 875,000 square feet and can accommodate up to 20,000 people — "intimate" is not the first word to come to mind. Still, the venue felt remarkably intimate during Dead & Company’s final performance of July.

This was owed in equal parts to its self-contained design and its immersive visual environment, in which Sphere’s LED screen wraps over and behind the audience. However uncannily, the latter contributes to a sense of closeness, creating the illusion that Sphere, its visual displays, and its audience are situated much more closely than they actually are.

Its 580,000-square-feet of LEDs, coupled with its 360-degree shape and structure, render Sphere the most immersive live music venue in the world. To that end, it’s not hyperbolic or unreasonable to call Dead Forever Dead & Company’s most immersive live venture yet.

Of course, the Dead Forever narrative — a trip through space undertaken together, as one community — only adds to the show’s combined sense of intimacy and immersion.

No Show Is The Same

It’s not out of character for Dead & Company to play no repeats across consecutive evenings (as they did at San Francisco’s Oracle Park, where they laid their touring career to rest last July), and Dead Forever is no exception. Apart from "Drums/Space" — the sole item on the setlist that recurs each night — the 17 other songs that the band will play and their visual accompaniments are left to Dead & Company’s whim.

"What’s become really interesting — and I would say it’s a challenge, but it’s a really fun one — is that not only do you have to make the songs work in some kind of a flow for the setlist, but every piece of content has maybe eight or 10 songs that can go with it," Mayer told Variety.

No show is the same, yielding similar but unique viewing experiences across a given residency weekend and, more broadly, the portfolio of Dead Forever shows performed to date. This aspect has enticed avid fans to return not once, not twice, but three times in a given weekend, to see a fuller scope of what Dead Forever has to offer across its many possible variations.

With the residency’s July run now in the rearview, Dead & Company will take a brief break before returning to Sphere Aug. 1-3 and 8-10 for the final Dead Forever trips — for now.

Explore The World Of Rock

HARDY On New Album 'Quit!!' & How "Trying To Push My Own Boundaries" Has Paid Off

A Beginner’s Guide To Phish: 8 Ways To Get Into The Popular Jam Band

Mexican Rockers The Warning On 'Keep Me Fed' & "The Possibility That We Could Literally Do Everything"

Watch Red Hot Chili Peppers Win Best Rock Album

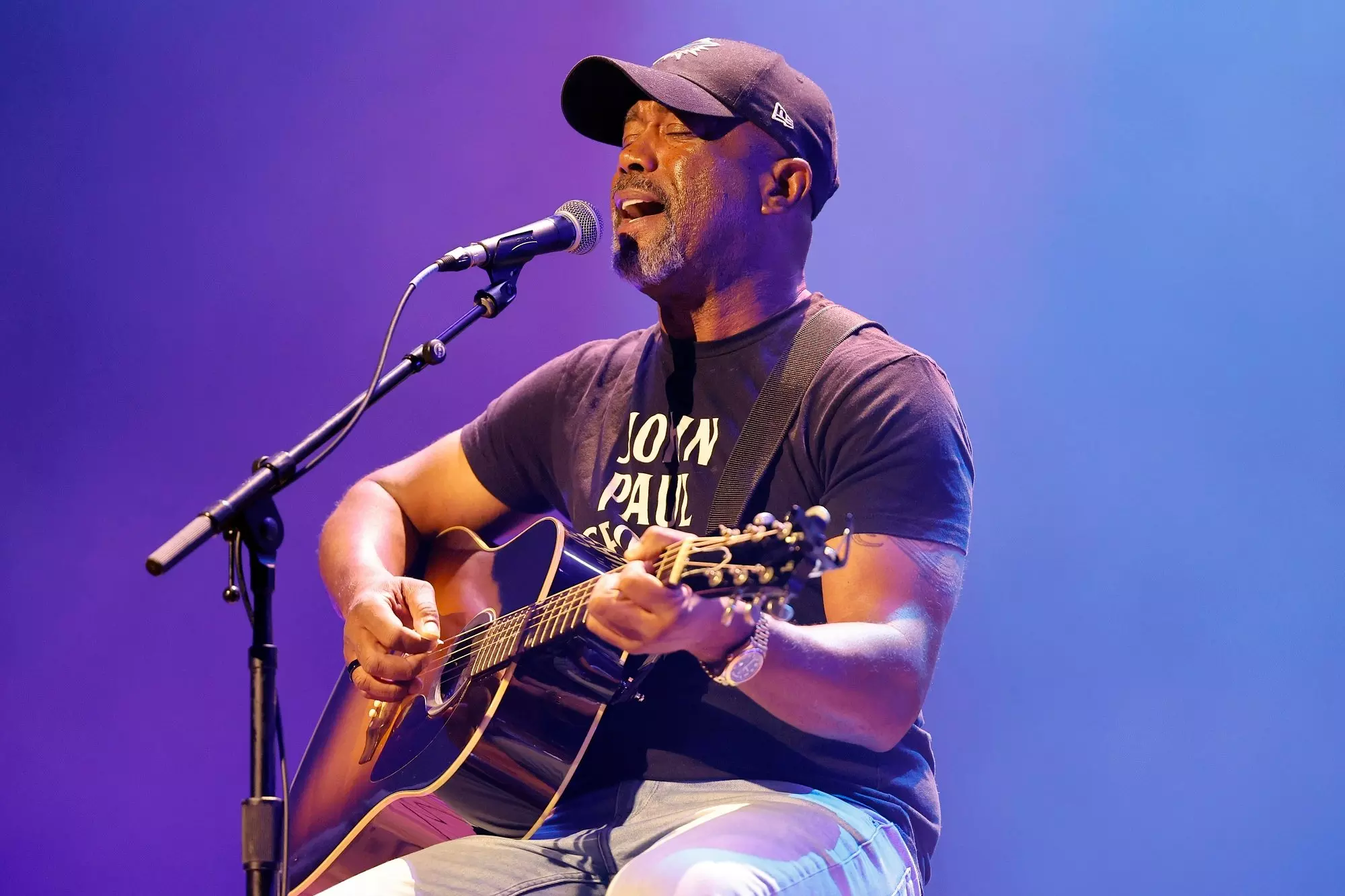

Darius Rucker Shares Stories Behind 'Cracked Rear View' Hits & Why He's Still Reveling In "A Dream Come True"

Photo: Nick Spanos

interview

Living Legends: How Dead & Company Drummer Mickey Hart Makes Visual Art From Vibrations — And Brought It To Las Vegas' Sphere

Dead & Company are currently embarking a residency at Las Vegas' sphere, which features drummer Mickey Hart's eye-popping, unconventional art. Hart spoke to GRAMMY.com about how it came to be, and how the Grateful Dead's legacy continues to ripple forth.

Living Legends is a series that spotlights icons in music who are still going strong today. This week, we interviewed Mickey Hart, one of two drummers — along with Bill Kreutzmann — of the Grateful Dead and its contemporary offshoot, Dead & Company.

His first-ever solo art exhibition, Art at the Edge of Magic, will run through July 13 at the Venetian Resort in Las Vegas, as part of the Dead Forever Experience. His work is also incorporated into their current residency at Las Vegas' Sphere.

After decades behind a drum kit with the Grateful Dead, and now in the same role in Dead & Company, Mickey Hart has learned a truly cosmic lesson: "The basis of all of creation is vibratory."

For years, in parallel with his legacy as a music maker, he's made visual art using a sui generis method, which has plenty in common with his techniques as a drummer. Check out his visual art, which he's been creating for years in parallel with his music making; some of it may look like paintings, but that doesn't quite describe what it is.

Rather, Hart employs vibrations — much like he's done behind the kit for decades — to bring out hitherto-invisible dimensions in paint. The results are captivating to the eye — at times, otherworldly.

The strength of Hart's visual art has added another layer to the Grateful Dead cosmos. If you're in or near Las Vegas, you can check out these works as part of the Dead Forever Experience, in an exhibition at the Venetian running until mid-July.

Additionally, if you catch Dead & Company during their Sphere residency (which runs through July 13), you can immerse yourself in it during the famous "Drums/Space" portion of the set — a percussive, celestial section stretching way back in Dead setlist history.

"I just love to do it. Sometimes, your hobbies overtake you and become a necessary ingredient in your life," Hart cheerily tells GRAMMY.com. "And that's what happened with this visual medium, that it kind of grew on me and made me want to go back over and over and over again to learn the craft."

Whether or not you'll be heading to Vegas, read on for an interview with Hart about how he makes these sumptuous textures and hues truly pop — as well as his gratitude for the potency and longevity of the Dead's afterlife. (No pun intended.)

This interview has been edited for clarity.

Your visual work is beautiful. What can you tell readers about how you make it — the brass tacks?

Well, I wouldn't say I paint. I don't use brushes — sometimes, once in a while — but really it's more of a pouring medium, and a spinning medium, and so forth. But I use vibrations in the painting process, and I think that's why people call it vibrational expressionism.

I use a subwoofer and the Pythagorean monochord — a stringed instrument — drives the subwoofer. Pythagoras, of course, invented it, and it goes down very low to 15 cycles, sometimes 10 cycles. And that vibrates the paint. I mix multiple colors, and the colors come up within each other, and it reveals these details that you cannot get in any other way.

And I just kind of fell on it. In the beginning, I was drumming them — beating underneath them and so forth. But now, I've progressed to using a Meyer subwoofer, and it works just fine. And that's how the paintings are born. They're vibrated into existence.

Once I apply my mumbo jumbo to it, and using additives that create unique features — shapes, people, animals, mountain ranges, glaciers — you see all kinds of things within the paintings if you look at them, and let yourself go, and become part of the paintings.

Everybody has their own interpretation of [what they reveal], which is really important. These are not, like, a rose, or a vase, or a car. It's not that kind of art form. So, it raises your consciousness. And if you can connect with it, you get high. And that's what these things are all about. That's what art's all about. No matter what it is, audio or visual, it's consciousness raising at its best.

I take it you've been developing this ability in parallel with your work in the Dead universe for some time.

Well, of course. I work with vibrations. The vibratory world is where I live, and I make my art there. It's always been like that. I'm a lover of low end; low frequencies are my specialty. And because I'm a percussionist and many of my drums are very large and they speak to the range, the frequency, which is not normally accessed.

So, I create these works using these low-frequency creations. And that was something that I fell on years ago, but as a hobby; this was nothing more than an escape to another virtual headspace. Now, I share it with others.

I feel like this sound-based approach to visual art is a fairly unexplored space.

For sure. I mean, you can look it up. I've looked it up. And when you look up vibrational expressionism, I'm the only one that's there. Someone coined that term years ago, and it's kind of fitting.

I might be unique in that particular way, but that's the only way I know how to bring the colors up within themselves and reveal the super details.

Photo: Emily Frost

And I'm sure this process is fluid and mutable; you don't apply the same technique for every piece.

Yes, I apply different frequencies and different rhythms to different paintings. They're not the same. Every time I approach it — whether it be a canvas, or wood, or plexiglass, or glass, or whatever the surface is — it's always different. I never repeat. Every one of them is unique.

It's about the mixing of the paints, and the ingredients I put in the paint. And then you have to let it go and you jam. That's what these works are — they're jams. Sometimes, I have a thought on how I want it to be, and then sometimes it'll completely change once I put paint to canvas.

You learn over years. I've been doing this for about 25 years as a hobby, so I've got hundreds of these. And some of them never see the light of day. That's the luck of the draw, but luck favors the prepared mind, and I prepare that before I go in. I focus and concentrate on not concentrating. I just try to be there now and let the flow happen.

I improvise. That's my love. That's the only thing I really know how to do. Memorizing things and repeating is not who I am. I don't paint by the numbers. You don't need me for that.

Much like what you do on stage!

The Grateful Dead never did memorize many things. It was mostly a seat-of-the-pants kind of art form, but you learn how to become a seat-of-the-pants artist, if you will. There's adventure, there's failure, there's success, there's luck, there's chaos, there's order, and back and forth.

The duality of all of that reflects life. It gets you high too. You can look at it and all of a sudden you're in a different, virtual space. That's what art does — good art, anyway. It puts you in a place of great wonder and awe.

Photo: Emily Frost

Can you talk about using the Sphere as a canvas for your work?

That's how I look at it — as a blank canvas. When I hit the stage, I'm not thinking of anything. I prepared, I have my skill, I'm ready to go, but I'm not really thinking in the normal sense of the word. I throw that away and I just feel muscle memory, you might call it.

When you're playing music in a band, you become a groupist. You learn to be able to interrelate between six people each having their own consciousness, making something larger than the parts. Music is great at that. But in painting, it's a singular thing.

Music is just the moving of air. That's the delivery system. It's the movement of air. And in this case, it's light. It's what the light does to you. The eye is more powerful than the ear as an organ. So people really react to the visual. Hopefully in the Sphere, there's a combination of both that come together and form something much larger.

I appreciate that you view a drum as far more than simply a drum.

It's not something that just played to keep time. It's something that is an integral part of the orchestra, right up there with melody and harmony. The primacy of rhythm is something that has come into music in this century. If you listen to the radio, it's rhythmic-driven, mostly. Of course, there's the melodies, but the basis of it all is rhythmic.

Visual art is the same thing. It's all about rhythm and flow. If you don't have that, you don't really have anything. You have to have a groove.

The basis of all of creation is vibratory. These arts are just miniatures of what's happening in the cosmos. I mean, we are in the wash of these vibrations that were created 13.8 billion years ago from the singularity, the big bang, and that's still washing over us. And that's where art comes in. It connects you to the infinite universe at its best.

You guys seemed to realize early on that you could transcend simply playing rock songs in a band.

When we were younger, we were all ingesting psychoactive drugs. They certainly freed our perspective, and created a different kind of perspective when we all played together. Some of it was drug-related, you might say. We took what we could from those experiences and created a new kind of music.

That was an important part of our exploratory nature as we were falling on Grateful Dead music. We were exploring realms of consciousness that were not accessible to us normally in a normal waking state. These chemicals certainly helped in that respect, used correctly and professionally. They were an enormous, enormous help.

And now we're finding out that LSD is being used in therapeutic and medicinal and diagnostics and all of that. These are very helpful in many ways.

Photo: Emily Frost

How has it felt watching the Grateful Dead turn into a franchise, a universe? This visual element at the Sphere adds a whole new layer to it.

Well, it's very interesting to see all the corners and of the universe that the Grateful Dead spirit has reached and all the people and all the bands that copy our music. It's very rewarding and complimentary, I think.

We knew it was special. First time I ever heard it, I knew it was special. How special? You never know, but you have to keep at it being special. And eventually, it skips generations, which is what we've done — generation, after generation, after generation. The parents share with their kids, their kids, their kids.

It's something that's very friendly — hanging out with your parents at a concert like that, and having a great time together, and sharing something that they shared when they were younger.

It's fantastic. It's unbelievable that it has that power. I was just talking to someone the other night and they asked me to explain it. You can't explain it in words. You have to hear it. You have to be there. You have to feel it. You have to feel the community that it spawns, and this feeling that you get in the music. It's very seductive, if you allow yourself that moment.

I was just reading this morning that Diplo — the electronic musician, a very good musician — just became a Deadhead the other night.

Really!

Oh, yeah. It transformed him completely. You never can tell who gets touched by our music. It's something that's not explainable, but it keeps going on. The people will not let it go.

As long as people are interested in our kind of music and our kind of scene, we'll keep playing. There's no end to it until we don't have the facility to play, or the rhythm stops. I plan to do this till the day I die. There's no question about it. I've always thought that. There's no secret.

I think Bob and I both agree on that, and all of the Grateful Dead, Bill, Phil, certainly Jerry, we're all in the same boat when it comes to Grateful Dead music, the passion that we bring to it. And it's very rewarding that people enjoy it as deeply as they do.

I tell you, I can't express the gratitude that I have just being part of it. We all feel that same way. It's very humbling, to be honest with you, that it's grown to be this. It was just a little cub. Now it's a roaring lion. It's just a gigantic monster that is always meant for the good, and that's very rewarding. It's a good life to lead. We work very hard at it.

A Beginner's Guide To The Grateful Dead: 5 Ways To Get Into The Legendary Jam Band

Photo: Timothy Norris/Getty Images

list

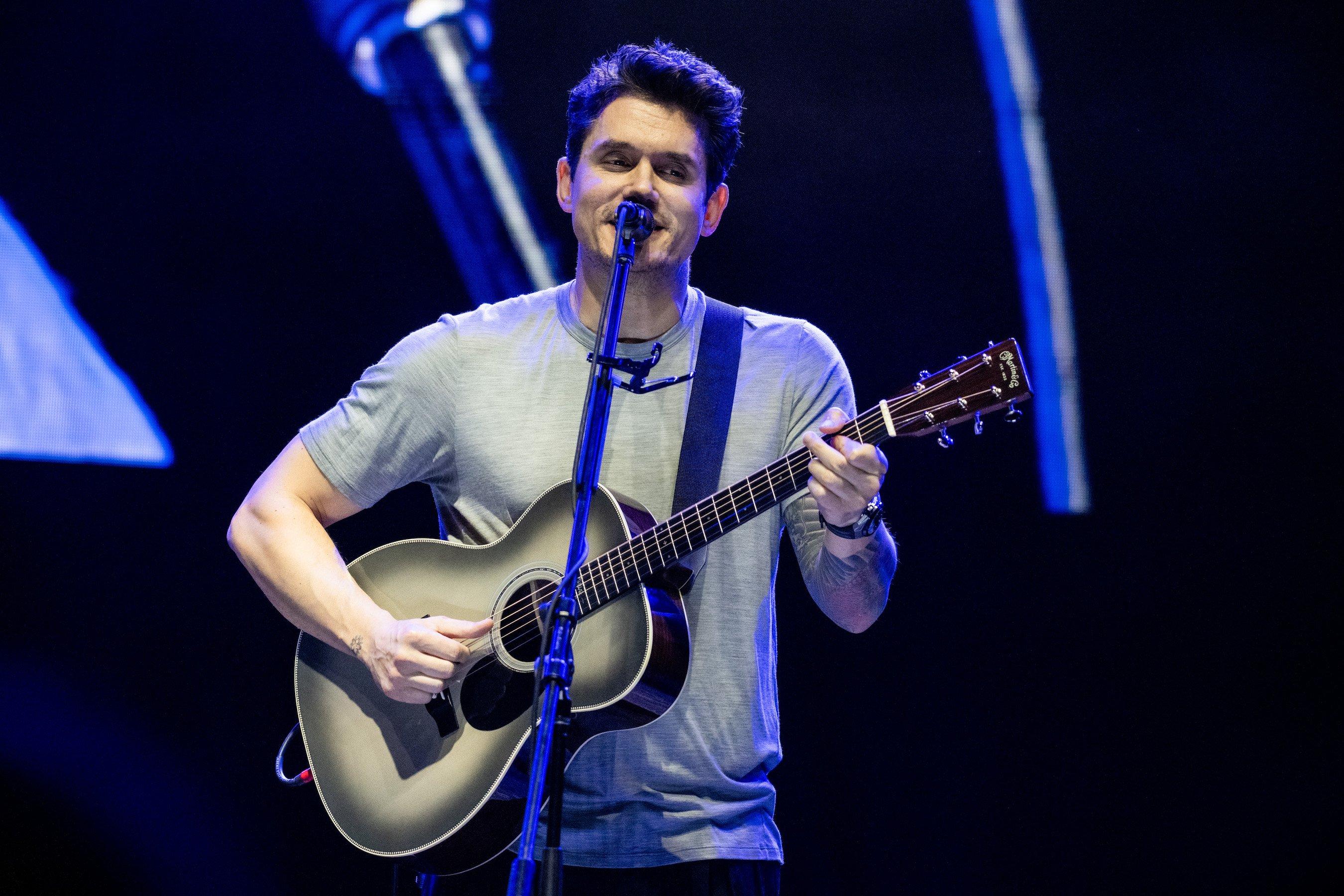

10 John Mayer Songs That Show His Versatility, From 'Room For Squares' To Dead & Co

As John Mayer launches his latest venture with Dead & Company — a residency at the Sphere in Las Vegas — revisit 10 songs that show every side of his musical genius.

At the 2003 GRAMMYs, a 25-year-old John Mayer stood on stage at Madison Square Garden, his first golden gramophone in hand. "I just want to say this is very, very fast, and I promise to catch up," he said with a touch of incredulity.

In the two decades that have followed his first GRAMMY triumph, it's safe to say that Mayer, now 46, has caught up. Not only has the freewheeling guitarist and singer/songwriter won six more GRAMMYs — he has also demonstrated his versatility across eight studio albums and countless cross-genre collaborations, including his acclaimed role in The Grateful Dead offshoot, Dead & Company. But the true testaments to his artistic range lie simply within the music.

Over the years, Mayer's dynamism has led him to work deftly and convincingly within a wide variety of genres, from jazz to pop to Americana. The result: an elastic and well-rounded repertoire that elevates 2003's "Bigger Than My Body" from hit single to self-fulfilling prophecy.

From March 2023 to March 2024, Mayer took his protean catalog on the road for his Solo Tour, which saw him play sold-out arenas around the world, mostly acoustic, completely alone. The international effort harkened back to Mayer's early career days, when standing alone on stage, guitar in hand, was the rule rather than the exception. Just after his second Solo leg last November, Mayer added radio programming and curation to his resume via the launch of his Sirius XM channel, Life with John Mayer. Fittingly, XM bills the channel (No. 14) as one notably "defined not by genre, but by the time of day, as well as the day of the week."

Mayer's next venture sees him linking back up with Dead & Company, for a 24-show residency at the Sphere in Las Vegas from May 16 to July 13. In honor of his latest move, GRAMMY.com explores the scope of Mayer's musical genius by revisiting 10 essential songs that demonstrate the breadth of his range, from the very beginning of his discography.

"Your Body Is A Wonderland," Room For Squares (2001)

The second single from Mayer's debut album, "Your Body Is A Wonderland" became an almost instant radio favorite like its predecessor, "No Such Thing," earning Mayer his second consecutive No. 1 on Billboard's Adult Alternative Airplay chart. The song's hooky pop structure provided an affable introduction to Mayer's lyrical skill by way of smart, suggestive simile and metaphor ("One mile to every inch of/ Your skin like porcelain/ One pair of candy lips and/ Your bubblegum tongue") ahead of Room For Squares' release later that June. The breathy hit netted Mayer his first career GRAMMY Award, for Best Male Pop Vocal Performance, at the 45th Annual GRAMMY Awards in 2003.

In recent years, Mayer — who penned the song when he was 21 — has chronicled his tenuous relationship with "Your Body is a Wonderland" in his infamous mid-concert banter, playfully critiquing the song's lack of "nuance." Following a perspective shift, Mayer has come to embrace his self-proclaimed "time capsule"; it was a staple of his set lists for his Solo Tour.

"Who Did You Think I Was," TRY! - Live in Concert (2005)

The product of pure synergy and serendipity, the John Mayer Trio assembled after what was intended to be a one-time stint on the NBC telethon, "Tsunami Aid: A Concert of Hope," in 2005. The benefit appearance lit the creative fuse between Mayer, bassist Pino Palladino and drummer Steve Jordan — who, over the years, have also played alongside the singer on his headline tours.

The John Mayer Trio propelled its eponymous artist from pop territory to a bluesy brand of rock 'n' roll that then demonstrated his talent as a live guitarist to its greatest degree yet. The Trio's first and only release, TRY! - Live in Concert, was recorded at their September 22, 2005 concert at the House of Blues in Chicago.

Mayer acknowledges his abrupt sonic gear shift on TRY! opener, "Who Did You Think I Was." "Got a brand new blues that I can't explain," he quips, then later asks, "Am I the one who plays the quiet songs/ Or is he the one who turns the ladies on?"

"Gravity," Continuum (2006)

Though "Waiting On the World to Change" was the biggest commercial hit from 2006's Continuum, "Gravity" remains the pièce de résistance of Mayer's magnum opus. Its status as such is routinely reaffirmed by the crowds at Mayer's concerts, whose calls for a live performance of his quintessential soul ballad can compete even with Mayer's mid-show remarks.

The blues-tinged slow burn marries Mayer's inimitable vocal tone with his guitar muscle on a record that strides far beyond the pop and soft rock of his preceding studio albums. Though Continuum builds on the blues direction Mayer ignited with TRY!, it does so with greater depth and technique, translating to a concept album, sonically, that evinces both his breakaway from the genres that launched his career and his skill as a blues guitarist — and "Gravity" is a prime example.

"I'm very proud of the song," Mayer mused on his Sirius XM station. "It's one of those ones that's gonna go with me through the rest of my life, and I'm happy it's in the sidecar going along with me."

"Daughters," Where the Light Is: John Mayer Live in Los Angeles (2008)

"Daughters" wasn't Mayer's first choice of a single for his sophomore LP, 2003's Heavier Things, but at Columbia Records' behest — "We really want it to go, we think it can be a hit," Mayer recalled of their thoughts — the soft-rock-meets-acoustic effort joined the album rollout. Columbia's suspicions were correct; "Daughters" topped Billboard's Adult Pop Airplay in 2004 — his only No. 1 entry on the chart to date.

But "Daughters" didn't just enjoy heavy radio rotation — it also secured Mayer his first and only GRAMMY win in a General Field Category. The Heavier Things descendant took the title of Song Of The Year at the 47th Annual GRAMMY Awards in 2005, helping Mayer evade music's dreaded "sophomore slump."

While the studio version may be the GRAMMY-winning chart-topper, Mayer's live rendition of "Daughters" during his December 8, 2007 performance at Los Angeles' Nokia Theater for Where the Light Is: John Mayer Live in Los Angeles compellingly demonstrated the power of the song — and his acoustic chops.

"Edge of Desire," Battle Studies (2009)

Come 2009, what critics almost unanimously proclaimed to be Mayer's biggest musical success had become his Achilles heel; everyone wanted another Continuum. But as they were to learn, Mayer never repeats himself. Thus came Battle Studies.

Born from a dismantling and transformative breakup, his fourth studio album arguably only becomes fully accessible to listeners after this rite of passage. Mired in introspection and pop rock, Battle Studies broadly engages with elements of pop with a sophistication that distinguishes it from Mayer's earlier traverses in pop and pop-inflected terrain.

His artistry hits a new apex on "Edge of Desire," a visceral and tightly woven song that remains one of the strongest examples of his mastery of prosody — the agreement between music and lyrics that results in a resonant and memorable listening experience.

"Born and Raised," Born & Raised (2012)

On the title track of his fifth studio album, Mayer distills growing up (and growing older) into a plaintive reflection on the involuntary, inevitable, and, in the moment, imperceptible phenomenon. He grapples with this vertigo of the soul on a record that, 12 years later, remains among his most barefaced lyrically.

The tinny texture of a harmonica, heard first in the intro, permeates the song, serving as its single most overt indicator of the larger stylistic shift that Born & Raised embodies. The 12-song set embraces elements of Americana, country and folk amid simpler-than-usual chord progressions for Mayer, whose restraint elevates the affective power of the album's lyricism.

"Born and Raised - Reprise," with which Born & Raised draws to a close, is evidence of Mayer's well-demonstrated dexterity. In its sanguine, folk spirit, the album finale juxtaposes "Born and Raised" both musically and lyrically. "It's nice to say, 'Now I'm born and raised,'" Mayer sings as the last grains of sand in Born & Raised's hourglass fall.

"Wildfire," Paradise Valley (2014)

Even before Paradise Valley hit shelves and digital streaming platforms, the cowboy hat that Mayer dons in the album artwork intimated that the hybrid of Americana, country, and folk he embraced on Born & Raised wasn't going anywhere — at least not for another album. The sunbaked project was a gutsy sidestep even further away from his successful commercial formula, and finds him expanding his stylistic fingerprint across 11 tracks that run the gamut of American roots music.

"Wildfire," the breezy toe-tapper with which Paradise Valley opens, grooves with Jerry Garcia influence. It is therefore unsurprising that many interpret "We can dance with dead/ You can rest your head on my shoulder/ If you want to get older with me," to be a lyrical nod to the Dead. Perhaps uncoincidentally, Mayer's invitation to become a member of Dead & Company came one year after the release of Paradise Valley.

"Shakedown Street," Live at Madison Square Garden (2017)

There is perhaps no better example of Mayer's dynamism than his integration in Dead & Company. The Grateful Dead offshoot, formed in 2015, intersperses Mayer among three surviving members of the band — Bob Weir, Mickey Hart, and Bill Kreutzmann — as well as two more newcomers, Oteil Burbridge and Jeff Chimenti. Mayer's off-the-cuff guitar solos and vocal support at Dead & Co's concerts are the keys that have unlocked a new plane of musicianship for Mayer, the solo artist.

This is evident on "Shakedown Street," a staple of The Grateful Dead's – and now, Dead & Company's – set lists. The languid, relaxed number gives Mayer the space to improvise guitar solos and use his vocals in a looser style than how he sings his own productions, all while feeding off the energy of his fellow band members. In addition to being one of The Dead's best-known songs, "Shakedown Street" is also the name of the makeshift bazaar where "Deadheads" socialize and sell wares ranging from grilled cheeses to drink coasters emblazoned with The Grateful Dead logo outside Dead & Company concerts.

Mayer's long, strange trip with (and within) the jam band has cross-pollinated his and The Grateful Dead's respective fandoms, attracting scores of Dead & Co listeners to his own headline shows, and vice versa. The takeaway: Mayer's involvement with Dead & Company offers a new, comparatively more rugged and improvisational lens through which to view his artistry.

"You're Gonna Live Forever in Me," The Search for Everything (2017)

"You're Gonna Live Forever in Me" evokes the sense of walking in, unexpected and undetected, to one of Mayer's writing sessions, watching him sing the freshly-penned piano ballad. This is owed to the song's abstract lyricism, the sentiment of which is deeply personal and universally accessible — a juxtaposition that's not often easy to achieve in songwriting. (Take, for example, "A great big bang and dinosaurs/ Fiery raining meteors/ It all ends unfortunately/ But you're gonna live forever in me.") But the studio version of "You're Gonna Live Forever in Me" also happens to be the original vocal take, adding to the feeling that Mayer is fully engrossed in a moment of poignant reflection mediated by music.

"I sat at the piano for hours teaching myself how the song might go. I sang it that night, and that was it…I couldn't sing the vocals again if I tried," Mayer recalled in a 2017 interview with Rolling Stone.

Mayer's lilted, Randy Newman-esque singing on the track finds him unintentionally but impactfully adopting a vocal technique distinctive from anything he's ever done before.

"Wild Blue," Sob Rock (2021)

Buoyed by a honeyed hook and slick production from No I.D., "New Light" was the unequivocal commercial standout of Sob Rock, a soft-grooving pastiche of '80s influence. Though the catchy pop-informed number finds Mayer stylistically diversifying by working with "The Godfather of Chicago Hip-Hop" (whose credits include Kanye West, JAY-Z, and Common, to name just a few), a look beyond the Sob Rock frontrunner reveals evidence of more sonic experimentation on the album.

Cue "Wild Blue." In its hushed, double-tracked vocals, the song plays like a love letter to JJ Cale. Mayer's whispery vocal emulation of the rock musician yields another new, but still polished, strain of John Mayer sound.

With hints of the '70s embedded within its taut production, "Wild Blue" is a beatific semi-departure from its parent album's '80s DNA. Together, they evince Mayer's ability to work not only across genres but also across sounds from different decades in music — further proof that his artistic range is both broad and timeless.

A Beginner’s Guide To The Grateful Dead: 5 Ways To Get Into The Legendary Jam Band

Photo: Meron Menghistab

interview

Cautious Clay's 'Karpeh' Is & Isn't Jazz: "Let Me Completely Deconstruct My Conception Of The Music"

On his Blue Note Records debut 'Karpeh,' Cautious Clay treats jazz not as a genre, but as a philosophy — and uses it as a launchpad for a captivating family story.

Nobody can deny Herbie Hancock is a jazz artist, but jazz cannot box him in. Ditto Quincy Jones; those bona fides are bone deep, but he's changed a dozen other genres.

Cautious Clay doesn't compare himself to those legends. But he readily cites them as lodestars — along with other genre-straddlers of Black American music, like Lionel Richie and Babyface.

Because this is a crucial lens through which to view him: he's jazz at his essence and not jazz at all, depending on how he wishes to express himself.

"I'm not really a jazz artist, but I feel like I have such a deep understanding of it as a songwriter and musician," the artist born Joshua Karpeh tells GRAMMY.com. "It's sort of inseparable from my approach to this album, and to this work with Blue Note."

Karpeh is talking about, well, KARPEH — his debut album for the illustrious label, which dropped in August. In three acts — "The Past Explained," "The Honeymoon of Exploration," and "A Bitter & Sweet Solitude," he casts his personal journey against the backdrop of his family saga.

As Cautious Clay explains, the title is a family name; his grandfather was of the Kru peoples in Liberia. "It's a family of immigrants. It's a family of, obviously, Black Americans," he notes. "I just wanted to give an experience that felt concrete and specific enough — to be able to live inside of something that was a part of my journey."

On KARPEH, Cautious Clay is joined by esteemed Blue Note colleagues: trumpeter Ambrose Akinmusire, saxophonist Immanuel Wilkins, vibraphonist Joel Ross, guitarist Julian Lage, and others.

Vocalist Arooj Aftab and bassist Kai Eckhardt — Karpeh's uncle — also enhance the proceedings. The result is another inspired entry from Blue Note's recent resurgence — one lyrically personal and aurally inviting.

Read on for an interview with Cautious Clay about his signing to Blue Note, leveling up his recording approach, and his conception of what jazz is — and isn't.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

Tell me about signing to Blue Note Records, and the overall road to KARPEH.

I kind of got connected to Don [Was, the president of Blue Note] through a relationship I had with John Mayer, who had, I guess, connected Don to my music.

Don reached out via email probably a year ago, and so we connected over email. And I had sort of been in a situation where I was like, OK, I want to do something different for this next project. We kind of met in the middle and it just made a lot of sense based on just what I wanted to do, and then what they could potentially kind of work with on my end.

So, [I was] just recording the album in six days, and doing a lot of prep work beforehand and getting all these musicians that I really liked to be able to work on it. It was just a really cool process to be able to unpack that with Blue Note.

That's great that you and Mayer go back.

Yeah, man, we have a song. We worked on each other's music a little bit together. The song "Carry Me Away" on his [2021] album [Sob Rock] I actually worked on, and then we did a song together called "Swim Home" that I released back in 2019.

You said you wanted to "do something different." What was the germ of that something?

I felt like it could be interesting to do a more instrumental album, or something that felt a little bit more like a concept album, or more experimental. I wanted to be more experimental in my approach to the music that I love.

I wanted to call it a jazz album, but at the same time I didn't, because I felt like it wasn't; it was more of an experimental album.

But I felt like calling it jazz in my mind kind felt like a free way to express, because I think of jazz much more as a philosophy than necessarily a genre.

So, it was helpful for me in my mind to be able to like, OK, let me completely deconstruct my conception of the music I make and how I can translate that music.

And then it eventually evolved into a story about my family and about American history to a certain extent in the context of my family's journey, and then also just their interpersonal relationships. That sort of made itself clear as I continued to write and I continued to delve deeper into the process.

Not that KARPEH ended up being instrumental. But instrumental records are lodestars for you? I'm sure that blurs with the Blue Note canon.

There's a lot of different stuff. There was that red album that Herbie Hancock released [in 1978, titled Sunlight] that I really liked. "I Thought It Was You" was super inspirational — sonically how they arranged a lot of that record.

Seventies jazz fusion was an overall influence. I felt inspired by the perfect meld of analog synthesizers, and then also obviously organic instruments like horns and guitars of that nature. So I wanted to create something that felt like a contemporary version of what could be a fusion record to a certain extent.

Any specific examples?

Songs like "Glass Face," for example, are pretty fusion-y, but also very just experimental in a way that doesn't feel like jazz, even.

My uncle [Kai Eckhardt] is a pretty big-time bass player, and he played on "Glass Face." I just was like, OK, dude, do your thing, and he just did this sort of chordal bass solo. Then, I did all these harmonies over top of the song.

And then, Arooj Aftab is a really good friend and musical artist; she was able to work off of that as well. So, it was an interesting journey to make a lot of these songs and sort of figure out how they all fit together.

How did you strike that balance between analog and synthesized sounds?

I recorded most of this album at a studio, which is very different for me.

I don't normally do that. I use a lot of found sounds like drums and stuff that I've either made or sampled, but I did all of the drums and bass and upright and electric guitars we'd recorded at a studio called Figure 8 in Brooklyn. That was the backbone for a lot of the music that I created for the album.

Then, I took it back home to my home studio. After we had recorded all of the songs, I essentially had some different analog synths and things that I wanted to add into it either at the studio that I worked at or my own personal studio, which happens to also be eight blocks [away] on the same street away.

I struck a balance just mostly with it in the context of working at a very formal studio and then having an engineer and just getting sounds that I wanted that could be organic and more specific in that way. And also using some of the synths they had.

In terms of the approach, I kind of wanted it to be different. And so part of that was just being at more of a formal studio and having an engineer and overseeing the overall process outside of just being inside of my Ableton session.

Tell me more about the guests on KARPEH.

I knew Immanuel through a couple of mutual friends, and he has a certain sort of bite to his sax playing that I felt was so juxtaposed to my sax playing.

And same with Ambrose. I feel like his trumpet style couldn't be more esoteric and out, in the context of how he approaches melodies. It's almost in some ways like, Whoa, I would never play that way.

They're also soloists, and conceptually for me, the idea of being in isolation or being in bittersweet solitude was conceptually a part of the last part of the album. They as soloists have so much to offer that I feel like I can't do and I don't possess.

So, I wanted to have them a part of this album, to demonstrate that individuality within the context of what it takes to make a song.

Julian is just a beautiful and spirited man, a beautiful guitar player. I've liked his sound for a while. I think it was back in 2015 when I first heard him; he had a couple of videos on YouTube that I thought were just super gorgeous.

I feel like he just has this way of playing that's folky. Also, it's jazz in the context of his virtuosic playing style, but it's also not overbearing. I felt like as a writer and as a musician, it would be a really great connecting point for a few of the more personal songs on the record.

And then my uncle Kai as well, — he's not on Blue Note, but he used to play with John McLaughlin and run bass clinics with Victor Wooten and Marcus Miller back in the early 2000s. Dude is a real heavy hitter, and he happens to be my uncle, so it's just cool to be able to have him on the record.

*Cautious Clay. Photo: Meron Menghistab*

With KARPEH out, where do you want to go from here — perhaps through a Blue Note lens?

I really love a lot of the people there, and I feel like this could be the first of many. It's also a stepping stone for me as an artist.

I feel really connected to the relationship I have, and our ability to put this out. It's hard to say what exactly the future holds, but I am genuinely excited for this album. I feel excited to be able to put out something so personal and so connected to everything that sort of made me, in a very concrete way.

From what I understand, this is a one-time thing, but it could potentially be two. It depends, obviously. I'm very open-minded about it. I'd love to keep the good relationship open and see where things go.

I really have enjoyed the process and I feel like this next year is going to be something interesting. So, we'll see.

On Her New Album, Meshell Ndegeocello Reminds Us "Every Day Is Another Chance"

Photo: Paras Griffin/Getty Images

interview

Joy Oladokun's 'Proof Of Life' Honors Her Own Experience — And Encourages Others To Do The Same

On her new album 'Proof of Life,' the Nigerian American singer/songwriter shares how she’s learned to embrace herself, remain hopeful, and be present when collaborating with her heroes.

In the first single off her forthcoming album, Proof of Life, Joy Oladokun sings, "I hate change, but I’ve come of age/Think I’m finally finding my way." Part of her coping strategy of late — in dealing with a world on fire, waters rising, anxiety rocketing — has been to sink deeper into her feelings, to reach a point of "pure acceptance."

"Living in America, I think we can very clearly see the damage that being resistant to the way the world changes can do to us," she tells GRAMMY.com. Two days before we spoke, six people — three of them children — were killed by a 28-year-old who fired 152 rounds of ammunition at a school in Nashville, where Oladokun has lived for the past six years. "Children are getting killed because we are intentionally misreading a document from 200 years ago."

Yet Oladokun was raised in the small farming town of Casa Grande, Arizona — a place where "people shot guns for fun, and we went mudding in our trucks." She continues, "I don't think people understand that I understand the culture because of what I look like."

An unabashedly queer Black singer/songwriter, the 31-year-old uses music to plant her flag in the ground of a world that has traditionally been presumptive and unwelcoming to someone like her. Someone who grew up listening to Bob Marley and Linkin Park, and was ostracized from the church-going community she was part of when she came out; someone who "hits all the high notes but still don’t got a seat in the choir."

Over the course of three albums, Oladokun has created a safe space, for herself and others, to deal with the highs and lows that being true to yourself can bring. "Most of my songs should feel like having a conversation with me on my porch; I tell you something deep about myself and ask if you’ve ever felt that way," she says.

Like many of the artists she grew up admiring, Oladokun’s music is rooted in folk with dashes of R&B, pop and an occasional sprinkling of Afrobeats mixed in — as evident in the Proof of Life track "Revolution," which features Nigerian American rapper Maxo Kream. Whether her voice hovers along a pristine guitar or piano track, as it does on "Somehow," or reaches for the edgier side of her personality, like on the sassy "We’re All Gonna Die" (featuring Noah Kahan), she never falters to be forthright and faithful to her values.

Oladokun played music throughout high school and worked as a church music minister with the intention of becoming a pastor before she lost that job when she came out. After landing in L.A., the singer thought she’d write for others as a living. Instead, she took a chance and started writing for herself. Now, after more than six years in Nashville, Oladokun’s songs have featured in shows like "Grey’s Anatomy" and "This Is Us", and she’s collaborated with Brandi Carlile and Jason Isbell.

She spoke with GRAMMY.com about accepting herself, keeping hope alive through her guitar, and getting advice from John Mayer.

Interview has been edited for length and clarity.

You're on tour with John Mayer. What has that been like so far?

It has been absolutely amazing and challenging and scary. I really, genuinely, am a fan of John Mayer's music, and I felt this way on the My Morning Jacket tour; I felt this way touring with Maren [Morris]. When I get called to play with people that I really respect, some nerves come through. But I do feel like I've been rising to the occasion and I spent a lot of time working on my craft and guitar playing. And not every show has been perfect but I feel like they've been good, and I've been able to be myself in some of the biggest stages and rooms I've ever played.

And just the fact that it's a solo acoustic show, and that John's been so kind and accommodating. Like yesterday, he gave me advice on how to deal with when people talk s—about you on the internet.

Yeah, you’d mentioned on Twitter about having a little difficult time. Did his advice help?

It totally helped because it also is like, Oh, he feels that way, too, you know? My favorite people to work with are the people who admit that they're still human and still processing how weird this job is on us as humans.

People were making comments about my laugh, which is like, I can't change that. I'm gonna be super candid: I'm a Black queer person doing something that I think at least 10 percent of the people in that room don't think I should be doing, just by virtue of me being me.

You have such a great laugh, though!

If you're not used to it, it can be sort of jarring. [Chuckles]

How have you learned to become more vulnerable in your songs?

I think it's mostly about dealing with the feelings. I have this deep, honestly kind of dark, obsession with artists that have died young, and I think about it a lot because I just am someone who struggles with my mental health.

I think I am trying to carve a path for all the people like me, or the people who have gone who were like me, to be able to do this, and to stay healthy, and to stay hopeful. And to say no, if they need to or to be human, and cry in front of people. I don't think people get that I am an actual human being with feelings and thoughts, who is processing the fact that I got asked to go on tour with a hero, and that is just as confusing to me as it is to you.

I sit in my hotel room, I practice guitar and I write songs. And I do everything I can to put my heart and my soul and myself out there in hopes that people of all different walks of life can relate. And that it will cause some people to think twice when they meet people like me in their day-to-day life. That’s what's driving me, and I think that's what brought me here.

On the days that it's scary and sad and I feel isolated, or I feel like everybody hates me, or I feel like I'm embarrassing John in arenas, it is good to remember that sometimes it might just help one person to see that I am me, and that I am doing this. And it doesn't matter how well I do it. It just matters that I'm here.

Are you reaching a point where you really recognize the part that you play in the world around you and articulating that?

I think I've always been a very purpose-centric person and artist, specifically. I have this painting in my studio that says "Remember why you started." I look at it every day, and I just remember when I started, when I inched into the music industry, I was like, "I’m gonna write songs for other people." And I just wanted to write songs that help.

I was doing a job where I was listening to the radio a lot, and I didn't relate to anything. So I just wanted to write songs that people could relate to. I still have that at the core of everything I do and say; it's just desperation to hold onto my humanity, and how that translates into art.

I'm not special. Like, I get that I sing songs for a living, and that not everybody has to like those songs. But I do know that in my heart of hearts, my purpose, and my role, and my goal is to just write songs that help me deal with life, and hopefully help one or two other people. That is something that I feel like I've been accomplishing so far. And until I feel like that isn't happening anymore, I think I wouldn’t continue on this path.

Can you pinpoint when you realized the power of being able to express yourself in a song?

My dad is a huge music fan. I’ve been thinking a lot about Bob Marley's impact on what I do. I think it was growing up listening to a lot of artists who were purpose-centric, like, just so rooted in, "I have something to say," or something to share with, and explain to, the world.

Lauryn Hill opened up the possibilities of hip-hop and how it could combine with folk and soul. Phil Collins and Peter Gabriel and Paul Simon were combining folk, rock and West African music and sounds and influences. I think it was growing up listening to people that were really intentional about every aspect of what they make. I feel like I went to school [by] listening to records.

Your Twitter bio used to say you were the "trap Tracy Chapman"…

It did. I am, right? [Chuckles]

It fits, yes!

Tracy Chapman being herself on stage allowed me as a kid to find an art form that helped me express myself and positively deal with a lot of heavy emotions. I think I'm, like, fine at what I do. I sometimes am a little confused as to why I get the opportunities that I get, but I do know that just by being as much of myself as I can, in whatever venue that I can be, I am doing that same thing for other people. And maybe that's just the value. Maybe I don't have to be the best.

Maybe in two years people won’t remember my name. But there will be a few hundred people who were scared or shy or felt like they were too Black or too queer or too different, whatever, to do anything, and then they show up to a John Mayer show too early, and here's my goofy ass thriving. Maybe that’s just it. Maybe I don't have to win awards. Maybe it really is just honestly, lighting the torch for someone who might be better than me to be able to do the same thing for other people.

"Sweet Symphony" is a lovely duet with Chris Stapleton about your parents. Have you tried to write about them before?

I have a few songs in the past that I've written about my parents. There's one called "Let It Be Me" that I wrote about my dad doing a really beautiful 180 when it comes to my sexuality. I have like this Crosby, Stills and Nash rip off thing apologizing to them for being chaotic when I was a kid.

One of my favorite things about my parents is that they're just in love. I would say my parents are two of the most in love people I've ever seen in my life. Growing up when my dad would come home from work, he would bring flowers from the store and then he would sing my mom like some goofy Motown song or whatever for the first five minutes when he got in. I just wanted to write a song that my dad could sing to my mom. I was in my apartment when I started it. I loaded up a piano on Logic, and I just started playing cheesy Motown chords. My dad still has the demo as his ringtone for when my mom calls.

We talk about all the things that have been hard between us but I think I explored that a lot in my last album. I am the fruit of my parents' love, and to be able to celebrate it with a really cool, amazing duet with Chris Stapleton feels like a blessing.

You performed at the White House during the signing ceremony for the Respect for Marriage Act in December last year, and yet you’re still self-effacing and unassuming. Are you able to realize the significance that your work, your music, has?

I am working through imposter syndrome. I think that's the current change that I'm dealing with. That's why the internet stuff it's hard, too, because not only do I not always feel worthy, I also feel, you shouldn't be here, too.

But I am trying to remember that it's not an accident that I am who I am on this planet at this time. And that's why being so vulnerable has become so important to me. I just try to bring that into every room. I've stopped joking about being mediocre. But I've honestly stopped grading my work. I don't know if it’s good or bad. I just work and create, and perform, and hopefully the heart of it, which is the most important thing to me, is what comes across.

6 Female-Fronted Acts Reviving Rock: Wet Leg, Larkin Poe, Gretel Hänlyn & More