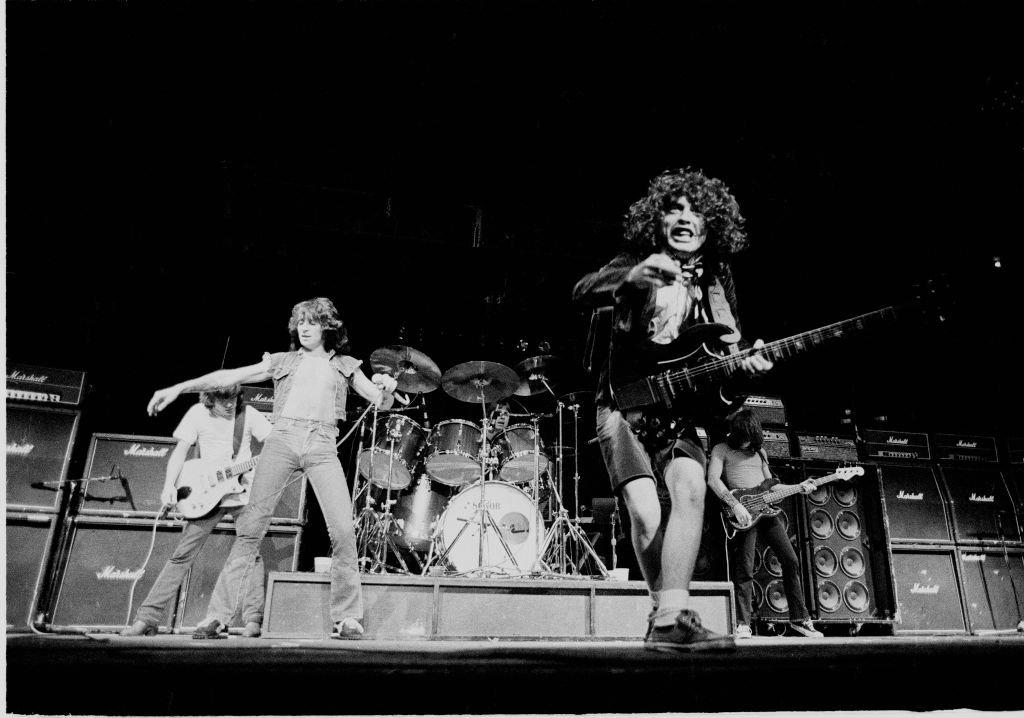

Photo by Michael Putland/Getty Images

AC/DC in 1979

news

Forget The Hearse: AC/DC's 'Back In Black' Turns 40

The classic-rock mainstays' seventh studio album—their first with Brian Johnson—took a longtime trope to its ultimate conclusion: Lead singers may succumb to mortality, but rock’n’roll would never

Back In Black is not a perfect album, but it may be the perfect rock album. What does that say about rock? Probably something about its built-in sexism circa 1980, with the level of horniness both constant and complacent for a band this elemental, more akin to a hostile work environment or catcalling or "locker room talk" than any singular artistic expression of coitus or the overpowering desire for it. "You Shook Me All Night Long"—which is not at all a bad choice for the best rock'n'roll song of all time—transcends the petty bra-snapping of surroundings like "Given the Dog a Bone" and "What You Do for Money Honey" by not only giving their object of desire some description ("American thighs" is probably their most important contribution to our language) but even some dialogue ("she told me to come but I was already there"—bummer). You're not going to get apologies from a band who recorded and released their comeback album in all of five months after their lead singer died. Especially not when his replacement literally sings the words "I never die," as if explaining why he's more cut out for the position. So I digress.

AC/DC's 50-times-platinum masterpiece (25 million of which were shipped domestic) could be the definitive rock album simply for being equidistant from Led Zeppelin IV and Nevermind, in some kind of sales apex window that also includes the Eagles' Greatest Hits and Michael Jackson's Thriller but also probably tops the curve by being so meat and potatoes there might not even be spuds. Kick, snare, kick, snare, kick, snare is rarely as primitive or as powerful as when "You Shook Me All Night Long" loses its intro like tearaway pants. Slow it down to what we now know to be hip-hop speed and you get "Back In Black," a noncontroversial nomination for the greatest guitar riff of all time, which only Wayne Campbell can really decide. Ease it down even more and you get the hungover, bluesy crawl of "Rock and Roll Ain’t Noise Pollution," which didn’t really catch on as a bumper sticker but trudges the album to a close with the confidence as if it did. Back In Black being 40 perfectly parallels its most loyal demographic being in their 60s, an always-in-lockstep cosplay of themselves 20 years younger.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed/pAgnJDJN4VA' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Bon Scott choked on his vomit in the passenger seat after a drinking binge, and less than half a year later, the guy who filled his shoes sang "Have a Drink on Me." There wasn’t any real hesitation; if anything it weirded out the record company more when AC/DC were gonna make their album cover entirely black in tribute. (They were asked to at least provide an outline of the AC/DC logo over it; oh, branding.) Brian Johnson, the new guy, was tasked with writing a tribute song, but not "morbid," so "it has to be a celebration." What a job.

"Back In Black," though, the other song on this album that wouldn’t be a bad choice for the best rock’n’roll song of all time, more than fulfills this prophecy; we may as well go ahead and nominate it for the even more likely Best Riff of All Time award. Makes a great hip-hop song too, though you wouldn’t know it from any official releases since these knuckleheads are against sampling. Search YouTube to find Eminem and the Beastie Boys kicking it like the stomping groove deserves. But those lyrics, which along with "Hells Bells" and "Noise Pollution" comprise the album's only verbiage not directed at women, are the perhaps the only time AC/DC was ever mysterious or impressionistic. Given, Steven Tyler and Anthony Kiedis rap things like "nine lives, cat’s eyes" all the time. But for a band this literal, this nearly artless in their glandular pursuits, it’s Picasso.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed/dN61WU57zBw' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

AC/DC identified something in punk and new wave. From Led Zeppelin to Black Sabbath to Deep Purple and even Aerosmith at their most talk-box spacy, hard rock in the 1970s was celebrated for its psychedelic excess, its pretensions. Elongated, folksy mandolin intros. The simulated endlessness of drum soloing. "Jams." But while AC/DC surely imbibed plenty of the same substances, they ran a no-nonsense assembly line of riffs compiled like car parts into well-oiled machines, no dirt or mess. There’s definitely some Ramones in that. If not for Kiss, you might even be able to say they were the first of this kind, and that Back In Black may have foreseen the coldness of Reagan in its defiance of feeling; for a tribute to a fallen friend, they didn’t even allow a single ballad. "Back In Black" may as well be about how stylish they looked at Bon Scott’s funeral. But it’s clear that Scott wouldn’t have blinked; if anything he would’ve climbed out of the casket to shriek "Shoot to Thrill" himself. And in a way, Back in Black may have taken a longtime trope to its ultimate conclusion: Lead singers may succumb to mortality, but rock’n’roll would never.

He Stuck Around: Foo Fighters' Eponymous Debut Album Turns 25

interview

Slash's New Blues Ball: How His Collaborations Album 'Orgy Of The Damned' Came Together

On his new album, 'Orgy Of The Damned,' Slash recruits several friends — from Aerosmith's Steven Tyler to Demi Lovato — to jam on blues classics. The rock legend details how the project was "an accumulation of stuff I've learned over the years."

In the pantheon of rock guitar gods, Slash ranks high on the list of legends. Many fans have passionately discussed his work — but if you ask him how he views his evolution over the last four decades, he doesn't offer a detailed analysis.

"As a person, I live very much in the moment, not too far in the past and not very far in the future either," Slash asserts. "So it's hard for me to really look at everything I'm doing in the bigger scheme of things."

While his latest endeavor — his new studio album, Orgy Of The Damned — may seem different to many who know him as the shredding guitarist in Guns N' Roses, Slash's Snakepit, Velvet Revolver, and his four albums with Myles Kennedy and the Conspirators, it's a prime example of his living-in-the-moment ethos. And, perhaps most importantly to Slash, it goes back to what has always been at the heart of his playing: the blues.

Orgy Of The Damned strips back much of the heavier side of his playing for a 12-track homage to the songs and artists that have long inspired him. And he recruited several of his rock cohorts — the likes of AC/DC's Brian Johnson, Aerosmith's Steven Tyler, Gary Clark Jr., Iggy Pop, Beth Hart, and Dorothy, among others — to jam on vintage blues tunes with him, from "Hoochie Coochie Man" to "Born Under A Bad Sign."

But don't be skeptical of his current venture — there's plenty of fire in these interpretations; they just have a different energy than his harder rocking material. The album also includes one new Slash original, the majestic instrumental "Metal Chestnut," a nice showcase for his tastefully melodic and expressive playing.

The initial seed for the project was planted with the guitarist's late '90s group Slash's Blues Ball, which jammed on genre classics. Those live, spontaneous collaborations appealed to him, so when he had a small open window to get something done recently, he jumped at the chance to finally make a full-on blues album.

Released May 17, Orgy Of The Damned serves as an authentic bridge from his musical roots to his many hard rock endeavors. It also sees a full-circle moment: two Blues Ball bandmates, bassist Johnny Griparic and keyboardist Teddy Andreadis, helped lay down the basic tracks. Further seizing on his blues exploration, Slash will be headlining his own touring blues festival called S.E.R.P.E.N.T. in July and August, with support acts including the Warren Haynes Band, Keb' Mo', ZZ Ward, and Eric Gales.

Part of what has kept Slash's career so intriguing is the diversity he embraces. While many heavy rockers stay in their lane, Slash has always traveled down other roads. And though most of his Orgy Of The Damned guests are more in his world, he's collaborated with the likes of Michael Jackson, Carole King and Ray Charles — further proof that he's one of rock's genre-bending greats.

Below, Slash discusses some of the most memorable collabs from Orgy Of The Damned, as well as from his wide-spanning career.

I was just listening to "Living For The City," which is my favorite track on the album.

Wow, that's awesome. That was the track that I knew was going to be the most left of center for the average person, but that was my favorite song when [Stevie Wonder's 1973 album] Innervisions came out when I was, like, 9 years old. I loved that song. This record's origins go back to a blues band that I put together back in the '90s.

Slash's Blues Ball.

Right. We used to play "Superstition," that Stevie Wonder song. I did not want to record that [for Orgy Of The Damned], but I still wanted to do a Stevie Wonder song. So it gave me the opportunity to do "Living For The City," which is probably the most complicated of all the songs to learn. I thought we did a pretty good job, and Tash [Neal] sang it great. I'm glad you dig it because you're probably the first person that's actually singled that song out.

With the Blues Ball, you performed Hoyt Axton's "The Pusher" and Robert Johnson's "Crossroads," and they surface here. Isn't it amazing it took this long to record a collection like this?

[Blues Ball] was a fun thrown-together thing that we did when I [was in, I] guess you call it, a transitional period. I'd left Guns N' Roses [in 1996], and it was right before I put together a second incarnation of Snakepit.

I'd been doing a lot of jamming with a lot of blues guys. I'd known Teddy [Andreadis] for a while and been jamming with him at The Baked Potato for years prior to this. So during this period, I got together with Ted and Johnny [Griparic], and we started with this Blues Ball thing. We started touring around the country with it, and then even made it to Europe. It was just fun.

Then Snakepit happened, and then Velvet Revolver. These were more or less serious bands that I was involved in. Blues Ball was really just for the fun of it, so it didn't really take precedence. But all these years later, I was on tour with Guns N' Roses, and we had a three-week break or whatever it was. I thought, I want to make that f—ing record now.

It had been stewing in the back of my mind subconsciously. So I called Teddy and Johnny, and I said, Hey, let's go in the studio and just put together a set and go and record it. We got an old set list from 1998, picked some songs from an app, picked some other songs that I've always wanted to do that I haven't gotten a chance to do.

Then I had the idea of getting Tash Neal involved, because this guy is just an amazing singer/guitar player that I had worked with in a blues thing a couple years prior to that. So we had the nucleus of this band.

Then I thought, Let's bring in a bunch of guest singers to do this. I don't want to try to do a traditional blues record, because I think that's going to just sound corny. So I definitely wanted this to be more eclectic than that, and more of, like, Slash's take on these certain songs, as opposed to it being, like, "blues." It was very off-the-cuff and very loose.

It's refreshing to hear Brian Johnson singing in his lower register on "Killing Floor" like he did in the '70s with Geordie, before he got into AC/DC. Were you expecting him to sound like that?

You know, I didn't know what he was gonna sing it like. He was so enthusiastic about doing a Howlin' Wolf cover.

I think he was one of the first calls that I made, and it was really encouraging the way that he reacted to the idea of the song. So I went to a studio in Florida. We'd already recorded all the music, and he just fell into it in that register.

I think he was more or less trying to keep it in the same feel and in the same sort of tone as the original, which was great. I always say this — because it happened for like two seconds, he sang a bit in the upper register — but it definitely sounded like AC/DC doing a cover of Howlin' Wolf. We're not AC/DC, but he felt more comfortable doing it in the register that Howlin' Wolf did. I just thought it sounded really great.

You chose to have Demi Lovato sing "Papa Was A Rolling Stone." Why did you pick her?

We used to do "Papa Was A Rolling Stone" back in Snakepit, actually, and Johnny played bass. We had this guy named Rod Jackson, who was the singer, and he was incredible. He did a great f—ing interpretation of the Temptations singing it.

When it came to doing it for this record, I wanted to have something different, and the idea of having a young girl's voice telling the story of talking to her mom to find out about her infamous late father, just made sense to me. And Demi was the first person that I thought of. She's got such a great, soulful voice, but it's also got a certain kind of youth to it.

When I told her about it, she reacted like Brian did: "Wow, I would love to do that." There's some deeper meaning about the song to her and her personal life or her experience. We went to the studio, and she just belted it out. It was a lot of fun to do it with her, with that kind of zeal.

You collaborate with Chris Stapleton on Fleetwood Mac's "Oh Well" by Peter Green. I'm assuming the original version of that song inspired "Double Talkin' Jive" by GN'R?

It did not, but now that you mention it, because of the classical interlude thing at the end... Is that what you're talking about? I never thought about it.

I mean the overall vibe of the song.

"Oh Well" was a song that I didn't hear until I was about 12 years old. It was on KMET, a local radio station in LA. I didn't even know there was a Fleetwood Mac before Stevie Nicks and Lindsey Buckingham. I always loved that song, and I think it probably had a big influence on me without me even really realizing it. So no, it didn't have a direct influence on "Double Talkin' Jive," but I get it now that you bring it up.

Was there something new that you learned in making this album? Were your collaborators surprised by their own performances?

I think Gary Clark is just this really f—ing wonderful guitar player. When I got "Crossroads," the idea originally was "Crossroads Blues," which is the original Robert Johnson version. And I called Gary and said, "Would you want to play with me on this thing?"

He and I only just met, so I didn't know what his response was going to be. But apparently, he was a big Guns N' Roses fan — I get the idea, anyway. We changed it to the Cream version just because I needed to have something that was a little bit more upbeat. So when we got together and played, we solo-ed it off each other.

When I listen back to it, his playing is just so f—ing smooth, natural, and tasty. There was a lot of that going on throughout the making of the whole record — acclimating to the song and to the feel of it, just in the moment.

I think that's all an accumulation of stuff that I've learned over the years. The record probably would be way different if I did it 20 years ago, so I don't know what that evolution is. But it does exist. The growth thing — God help us if you don't have it.

You've collaborated with a lot of people over the years — Michael Jackson, Carole King, Lemmy, B.B. King, Fergie. Were there any particular moments that were daunting or really challenging? And was there any collaboration that produced something you didn't expect?

All those are a great example of the growth thing, because that's how you really grow as a musician. Learning how to adapt to playing with other people, and playing with people who are better than you — that really helps you blossom as a player.

Playing with Carole King [in 1993] was a really educational experience because she taught me a lot about something that I thought that I did naturally, but she helped me to fine tune it, which was soloing within the context of the song. [It was] really just a couple of words that she said to me during this take that stuck with me. I can't remember exactly what they were, but it was something having to do with making room for the vocal. It was really in passing, but it was important knowledge.

The session that really was the hardest one that I ever did was [when] I was working with Ray Charles before he passed away. I played on his "God Bless America [Again]" record [on 2002's Ray Charles Sings for America], just doing my thing. It was no big deal. But he asked me to play some standards for the biopic on him [2004's Ray], and he thought that I could just sit in with his band playing all these Ray Charles standards.

That was something that they gave me the chord charts for, and it was over my head. It was all these chord changes. I wasn't familiar with the music, and most of it was either a jazz or bebop kind of a thing, and it wasn't my natural feel.

I remember taking the chord charts home, those kinds you get in a f—ing songbook. They're all kinds of versions of chords that wouldn't be the version that you would play.

That was one of those really tough sessions that I really learned when I got in over my head with something. But a lot of the other ones I fall into more naturally because I have a feel for it.

That's how those marriages happen in the first place — you have this common interest of a song, so you just feel comfortable doing it because it's in your wheelhouse, even though it's a different kind of music than what everybody's familiar with you doing. You find that you can play and be yourself in a lot of different styles. Some are a little bit challenging, but it's fun.

Are there any people you'd like to collaborate with? Or any styles of music you'd like to explore?

When you say styles, I don't really have a wish list for that. Things just happen. I was just working with this composer, Bear McCreary. We did a song on this epic record that's basically a soundtrack for this whole graphic novel thing, and the compositions are very intense. He's very particular about feel, and about the way each one of these parts has to be played, and so on. That was a little bit challenging. We're going to go do it live at some point coming up.

There's people that I would love to play with, but it's really not like that. It's just whatever opportunities present themselves. It's not like there's a lot of forethought as to who you get to play with, or seeking people out. Except for when you're doing a record where you have people come in and sing on your record, and you have to call them up and beg and plead — "Will you come and do this?"

But I always say Stevie Wonder. I think everybody would like to play with Stevie Wonder at some point.

Incubus On Revisiting Morning View & Finding Rejuvenation By Looking To The Past

Photo: Jeff Kravitz/FilmMagic

video

GRAMMY Rewind: Kendrick Lamar Honors Hip-Hop's Greats While Accepting Best Rap Album GRAMMY For 'To Pimp a Butterfly' In 2016

Upon winning the GRAMMY for Best Rap Album for 'To Pimp a Butterfly,' Kendrick Lamar thanked those that helped him get to the stage, and the artists that blazed the trail for him.

Updated Friday Oct. 13, 2023 to include info about Kendrick Lamar's most recent GRAMMY wins, as of the 2023 GRAMMYs.

A GRAMMY veteran these days, Kendrick Lamar has won 17 GRAMMYs and has received 47 GRAMMY nominations overall. A sizable chunk of his trophies came from the 58th annual GRAMMY Awards in 2016, when he walked away with five — including his first-ever win in the Best Rap Album category.

This installment of GRAMMY Rewind turns back the clock to 2016, revisiting Lamar's acceptance speech upon winning Best Rap Album for To Pimp A Butterfly. Though Lamar was alone on stage, he made it clear that he wouldn't be at the top of his game without the help of a broad support system.

"First off, all glory to God, that's for sure," he said, kicking off a speech that went on to thank his parents, who he described as his "those who gave me the responsibility of knowing, of accepting the good with the bad."

Looking for more GRAMMYs news? The 2024 GRAMMY nominations are here!

He also extended his love and gratitude to his fiancée, Whitney Alford, and shouted out his Top Dawg Entertainment labelmates. Lamar specifically praised Top Dawg's CEO, Anthony Tiffith, for finding and developing raw talent that might not otherwise get the chance to pursue their musical dreams.

"We'd never forget that: Taking these kids out of the projects, out of Compton, and putting them right here on this stage, to be the best that they can be," Lamar — a Compton native himself — continued, leading into an impassioned conclusion spotlighting some of the cornerstone rap albums that came before To Pimp a Butterfly.

"Hip-hop. Ice Cube. This is for hip-hop," he said. "This is for Snoop Dogg, Doggystyle. This is for Illmatic, this is for Nas. We will live forever. Believe that."

To Pimp a Butterfly singles "Alright" and "These Walls" earned Lamar three more GRAMMYs that night, the former winning Best Rap Performance and Best Rap Song and the latter taking Best Rap/Sung Collaboration (the song features Bilal, Anna Wise and Thundercat). He also won Best Music Video for the remix of Taylor Swift's "Bad Blood."

Lamar has since won Best Rap Album two more times, taking home the golden gramophone in 2018 for his blockbuster LP DAMN., and in 2023 for his bold fifth album, Mr. Morale & the Big Steppers.

Watch Lamar's full acceptance speech above, and check back at GRAMMY.com every Friday for more GRAMMY Rewind episodes.

10 Essential Facts To Know About GRAMMY-Winning Rapper J. Cole

Photo: Travis Shinn

interview

The Twin Halves Of 'Mammoth II': Wolfgang Van Halen's Sorrow And Jubilation

Mammoth WVH's Wolfgang Van Halen created his latest album after his father's death. On 'Mammoth II,' the multi-instrumentalist faces the vertiginous highs and devastating lows of his last few years with unflinching rock.

There's no end to songs about times being fantastic, or gut-wrenchingly awful. It's rare for one to capture both in parallel — but Wolfgang Van Halen made a whole album of them.

The first tune he wrote for Mammoth II — which landed Aug. 4 — was "Another Celebration at the End of the World." (Naturally, it became the first single.) "A kiss, a casket, and all our rights and wrongs," he sings in the pre-chorus. "We're gonna take it back somehow."

From "Like a Pastime" ("Beat me up like a pastime/ Bring me up to the downside") to "Better Than You"'s dismantling of high horses, Mammoth II is one big yin and yang.

It's even in John Brosio's deliciously witty album art, where a skeleton in a folding chair can't enjoy a fireworks display because he's… well, you know.

"I just thought it was such a somber, dark, but almost sarcastic vibe to it that I just think really, really fit the music, and the album, and the band to a T," Van Halen tells GRAMMY.com of the cover. "I think it really represented my headspace throughout the creation of the album, and just in the last few years."

Which brings us to the elephant in the room: Van Halen's father, guitar titan Eddie, died in mid-2020 of a stroke following a years-long cancer battle.

His old man came up in a Twitter Spaces with GRAMMY.com last year; he said he was handling it terribly, but with a lilt in his voice. When reminded of this, Van Halen chuckles. "Everything's terrible," he admits. "But we're just trying to navigate it."

Within the grooves of his latest creation, the GRAMMY-nominated singer/songwriter and multi-instrumentalist seems to posit that there's nothing rock 'n' roll cannot heal.

Read on for the full interview with Van Halen about the road to Mammoth II, keeping his arrangements simple for maximum impact, and the band he and his father listened to more than any other.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

The first thing that struck me about Mammoth II is that it respected my intelligence. It wasn't constantly trying to impress me, beating me over the head with grabby moments. Because it's guitars, bass, drums, vocals and not much else, I could simply enjoy the songs.

Yeah, I think overcomplicating for the sake of overcomplicating is really dumb. I think you can have your moments, but it's more about the song. If anything gets in the way of the song, that's a problem. The song comes first.

Can you take me from the last Mammoth WVH album to Mammoth II?

The first album came out after my father had passed. I think, people think I was working through that on that album, and no. I finished recording that album in 2018.

All the things that have happened in my life since 2019, you hear on this album. Which I think is why, in comparison to the first, it's much darker and heavier.

While simultaneously, so many good things are happening. It's this kind of whiplash from left to right, of good and bad, and it's hard to keep track.

What were those good things? Career prospects, everything growing for you?

Yeah, just being able to build this and seeing people's response, which was so far out of my expectations.

People are actually really resonating with the material — I'm finally playing places more than once, and seeing more people show up, and more people singing. It's really crazy to see people sing your lyrics back at you.

I think overall with this album, I came into the process with a bit more confidence. Because, with the first one I was trying to figure out what it was or if I could even sing.

With this, I've been doing it for the last two years, so that desire to get great music out there that will be great to play live, was very much there. I think that's why it ended up being a bit more aggressive as well.

Seems like a lot of these new fans aren't showing up just because of your surname.

Exactly. That's the trip, seeing people when they're singing this stuff. It's like, Wow, you guys actually know it. You're not just here for that. It's crazy.

Can you talk about navigating the competitive modern rock landscape?

It's a tough thing, but luckily, I've built a very wonderful vehicle of management and band.

At every level of operation with Mammoth, there are wonderful people involved, and we're able to weather any storm together. I think that's a really important thing, to have people you trust.

I feel like we didn't hear many stories like that when your dad was on top of the world. I feel like every single act of his ilk was…

Getting taken advantage of.

Every single one, it seems.

Yeah, very common. Just growing up and seeing how things can be when they're bad made me strive more to build something from its inception. To be pure, and focused, and driven as a collective, instead of letting selfish interests ruin a good thing for everybody.

Can you talk about the first tune you wrote, or conceived, for the album?

"Another Celebration at the End of the World," which was the first single that we released, was the first song that came about.

It was sort of driven out of the desire to have some more uptempo, upbeat stuff. I think, compared to the first album, that was a bit groovier; there wasn't really stuff that was super quick.

So, that desire for a kind of punky, quick song came about with that one, and it sort of set the tempo — no pun intended — for the whole album. I think, again, that's what contributed to it being more aggressive and heavy.

What were you checking out at the time? I noticed a tinge of NWOBHM in there.

Oh, for sure. I really appreciate heavier music — things like Meshuggah, or Tool especially. I think on a song like "Optimist" on that album, my inspiration or influences creeped out a bit more, the more comfortable I was.

When you were growing up, what kinds of records did you and your dad check out?

AC/DC was, like, our band. Also, Peter Gabriel, [1986's] So. One of my favorite albums of all time. It was one of my dad's favorite albums as well.

Give me a tune on Mammoth II that bears the influence of either AC/DC or Peter.

AC/DC, for sure. I think the song "I'm Alright" has a throwback-y, sort of classic vibe.

But really, when it comes to Peter Gabriel's influence, it's melody more than anything, and that seeps through everything that I do. Melody is probably the most important thing to me; no matter how heavy a song gets, like "Right?" or "Optimist" or "Better Than You," melody is very much there, and an integral part and process of my songwriting.

Who are your other favorite melodists?

There's an Australian band called Karnivool that are very Tool-like in their heaviness. But I really appreciate the singer Ian Kenny and the way he's able to navigate the complication of the songwriting — the progressiveness — but inject melody to it.

I think that's a really admirable trait in that band — how he still manages to get sing-along vocals to an eight-minute prog-rock metal song.

When you write a melody, how do you conceptualize it?

For me, it's just kind of following my gut feeling — what wants to come out when you hear the music. Sometimes, I'll pull my hair out trying to figure stuff out and realize that I've had the melody the whole time, because it's what you immediately jump to when you hear it.

There are many, many moments on this album where I was like, "Oh, that's the melody!" because I wasn't even thinking of it.

Sometimes, you'll come up with joke lyrics. It's kind of like how "Yesterday" by the Beatles, was "Scrambled Eggs," when Paul McCartney was writing it. Because it was about the melody first, and sometimes you just have those melodies that come out by themselves before you realize it.

It reminds me of a Mitch Hedberg joke where he's talking about writing comedy bits: "If I think of something funny, I write it down and there you go. But, if I'm too tired or too far away from that pad of paper, I have to convince myself that what I thought of wasn't funny."

Because there's just that sort of vibe where it's like you're in bed and you're like, Dude, is this worth getting up? Is this thing in my head worth getting up and cataloging? And more often than not it is, but you can't really force whenever creative stuff happens.

Give me a song on Mammoth II where it felt like you had a melodic breakthrough.

I think "Better Than You," the last song on the album is a good representation of, sort of, the mission statement of the band as well — that no matter how heavy it gets, melody is still very prevalent.

And, I really enjoy that duality of the song where it's a really driving, heavy, sort of bendy riff, while the melody's incredibly sing-songy and Beatles-esque, kind of sitting on top of everything.

What made "Better Than You" the natural closing track?

With the first song on the album being very heavy, but melodic, it kind of put a period on that for the album. I think it's our first song to have really long fade out; it just fit perfectly for the album.

I think overall, just lyrically, it was an important statement to make. I think in this day and age, everybody thinks that they're so much better than everybody else, when really everyone's just as miserable as everyone else and trying to convince people that they're not.

Can you talk about your producer and engineer on Mammoth II?

It doesn't take much to make a Mammoth album. It's me, my producer Elvis Baskette, engineer Jef Moll, and Josh our assistant. You put the four of us in the studio, and you get a Mammoth album.

I think a lot of people, when they hear that I record everything on my own, they're sort of like, "Well, how do you get that sort of friction, that a collaborative effort with the band gets?" Elvis literally is that; he's sort of the other half when it comes to everything in the studio.

He helps keep me from doubting myself, making sure I'm on the right path, but also presents ideas that may be conflicting to what I'm presenting. It helps breed that creative environment in the best way possible. I couldn't do it without him.

Tell me about your drum thinking on the album.

I started playing when I was nine, so I feel like I'm most comfortable when playing drums. I think with my heavier influences, I just kind of let that take over on songs.

Like right after the solo. It's practically a Meshuggah djent part, through the lens of Mammoth. Which I think is really funny, because we've never done anything like that before.

I just think I have a really, really rhythmic approach to songwriting in general, and I think that's why everything sort of locks up between the guitar rips, and the bass, and the drums.

Extend this to your guitar approach. When it's time to take a solo, which of your heroes steps up to the plate, mentally speaking?

I'm not sure, because with that one, it was such a different thing for me in terms of writing a solo that I felt like I was kind of standing on my own, trying to figure out how to approach something like that. Because I really hadn't before.

Normally, my solos were really, really quick and to the point, and so to kind of explore that in a minute and a half was a really fun, new thing for me.

But overall, considering I played my dad's original Frankenstein guitar, through his original Marshall Head and Cabinet on the solo, it just felt like a right thing to have him there with me on that. I think it was really, really cool to have that be a part of the song.

There's so much history ingrained in it; you can really feel it. It's a very special thing. I thought it was important to have it show up on this.

*Wolfgang Van Halen performing at O2 Academy Edinburgh in Scotland, 2023. Photo: Roberto Ricciuti/Redferns*

To close out, what is Mammoth II a bridge to? What can you do now that you've made this?

I'm really not sure. It's funny; it almost stresses me out thinking about doing the next album, because we have so much going on with this.

But I just think it's important to do what I did with this album compared to the first, which is just to explore and see where else I can take it, while still being underneath the same umbrella.

I do already have some ideas that could be softer, or just a different flavor, and I think that's what this album did compared to the first song. I'm really excited to just keep exploring the sound — and what Mammoth is capable of.

.jpg)

Photo: Ross Halfin

interview

Living Legends: Def Leppard's Phil Collen Was The Product Of A Massive Transition For Music — And He Wouldn't Change A Thing

Def Leppard is out with a new collaborative album with the Royal Philharmonic, 'Drastic Symphonies.' In an interview with GRAMMY.com, guitarist Phil Collen gets in a reflective mood about their early days of hysteria — and euphoria — in the studio.

Living Legends is a series that spotlights icons in music still going strong today. This week, GRAMMY.com spoke with Phil Collen, the guitarist of Rock and Roll Hall of Famers Def Leppard for more than four decades. Their latest studio album, Diamond Star Halos, was released in 2022; their new album with the Royal Philharmonic, Drastic Symphonies, is available May 16.

By any standard, the 1980s were a transitional era for popular music, a rubicon crossed.

That had a lot to do with emerging technology, which led some to sink and others to swim. While the drift to synths and sequencers left some classic rockers beached, artists from Madge to Prince and Paul Simon flourished. And that trial-by-digital gave us the one and only Def Leppard.

Def Leppard's new release, Drastic Symphonies, out May 16, acts as the opposite point of this arc, proving that the band is adaptable to both tech and the timeless nature of classical music.

Reimagined with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, Drastic Symphonies may be a program of hits (like "Animal" and "Pour Some Sugar on Me") and deep cuts (like "Paper Sun"), but it is far from typical.

Rather, Drastic Symphonies’ splendorous, cinematic treatment provides a window into their tunes’ innate malleability and longevity — while giving their legacy something of a consolidative This Is Your Life treatment.

"It gives it that third dimension that you always want to hear,” Phil Collen, their guitarist of more than 40 years, proudly tells GRAMMY.com over Zoom. “It was a beautiful experience, I've gotta say."

Collen's head is full of memories of that pivotal decade — the one where they were "selling sometimes a million records in a week." If you imagine Def Leppard as being rowdy and recalcitrant in the studio back then, like their current tourmates Mötley Crüe — think again. Under producer extraordinaire Robert "Mutt" Lange, they were perfectionists, breathing the maximum amount of imagination into every song.

"You have this image in your head, and it was creating it for audio," Collen recalls of the era that produced classics like 1983's Pyromania and 1987's Hysteria. "[Lange] always used to say, 'Look, we've got to create Star Wars for the ears."

Operating by that celestial edict, Def Leppard succeeded and then some: they've sold more than 100 million records worldwide, and were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2019. "We're ticking every box," Collen says. "And a lot of these boxes we didn't quite tick in the '80s."

Read on for a rangey interview with Collen about Diamond Star Halos a year on, the genesis of Drastic Symphonies and the state of Def Leppard.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

What's it been like living with Diamond Star Halos over the past year?

It's been great in the fact that we've actually been touring it, and it's been getting accepted as we've been playing it. You know, when you release a new album, it's like: no one really wants to hear it live. They just want to hear all the hot chestnuts — all the older stuff. But we feel this is genuinely, fully integrated into the live set. We're doing, like, three songs, and one of them we're doing acoustically.

I love the album, looking back at it. It's amazing. We felt like we celebrated our heroes on it — everything about the Bowie, T. Rex, Queen era. I think we hit the mark with that one.

Since Def Leppard is still an actively creative enterprise, how do you navigate that tension between the old and the new? You're not devoted to, as David Crosby memorably put it, "turning on the smoke machine and playing the hits."

Well, now you gave me an idea — we'll put the smoke machine on during the new songs!

We just follow the Stones' lead on that. Every time they go out, they carefully place a new song. They know they've got to do "Jumpin' Jack Flash" and "Satisfaction" and all that stuff. We just do that — we integrate it in there.

You've just got to be careful. It's great doing [it as a] first song, because you can use the theatrics of "Here we are." There's a lull at a certain point, and you inject something like that. We're very careful about where and when we put them in the set.

Who were your role models in the early Def Leppard days? Who did you look to and say, "I want to perform live, or make records, or have a career like them"?

It's always been the rock-ness of AC/DC but the finesse of Queen, and the great songs that Queen had. We like to tour like the Rolling Stones but have the caliber of appreciation of Queen. We're kind of getting there, to an extent. But they are the two pillars, I guess, that we kind of base the whole thing on.

Tell me about your relationship to symphonic music, and pave the road to the Royal Philharmonic album. Def Leppard and your peers have always had something of a symphonic sweep, so this seems like the most natural thing in the world.

It is. On "When Love and Hate Collide" and "Two Steps Behind," we had an orchestra. "Let Me Be the One," a song we did in the late '90s [and released in 2002, also did]. Especially ballads lend themselves really well to that.

This came up about a year ago, when we were over in England doing promo for Diamond Star Halos and getting the whole thing sorted out. It just got suggested by the label.

[The Royal Philharmonic] was doing this series of albums of bands like Queen and Pet Sounds by the Beach Boys. We wanted to be involved in it; we didn't just want an orchestra playing our stuff. So, we got into the arrangements; we got our string arranger guy who worked on Diamond Star Halos, Eric Gorfain.

It really worked. And some of the songs absolutely didn't work. They sounded wrong and kind of comical in some respects. We had to demo each song with a keyboard string arrangement, and it was really easy. It was like black or white, yes-no.

Were you in Abbey Road Studios, working with the string players on a hands-on level? What was the nature of the interchange between the band and orchestra?

They played all their stuff live. It was a year of preparation. Eric scored it all out. Ronan McHugh, our front sound guy and producer and everything, got in touch with the producer, Nick Patrick, and all of us met up at Abbey Road. We were there when strings were done.

That was really an icing-on-the-cake type thing. All the prep work had been done — on some of the songs, we'd leave guitars and drums out for whole sections and let the orchestra breathe.

But we'd done that all before, so it was just them literally playing to the conductor and us sitting in the control room hearing this wonderful cacophony coming back, of us playing with them.

Songs like "Paper Sun," which is kind of a deep cut off [1999's] Euphoria, just works so well with an orchestra. It gives it that third dimension that you always want to hear. So, yeah, it was a beautiful experience, I've gotta say.

I think we tend to think of classic songs as preordained — that they'd inevitably come into existence and bake themselves into culture. Back when you guys actually wrote and recorded hits like "Pour Some Sugar On Me," was there any attitude that would be modern standards 40 years on?

This is really funny, actually. I remember Mutt Lange, our producer, 37 years ago or something like that — someone came into the room and said, "The album's taking so long! Why do you spend so much time?" He said, "So that you'll be talking about it in 40 years." He actually said that!

Wow.

Certainly, Mutt Lange had the vision of it. We were just part of his vision!

Sounds like you guys were serious perfectionists in the studio — deeply focused on the product.

We were. And I think we overdid it a little bit, because we'd be there from 10 in the morning 'til 2 the next morning and not take weekends off. As we've gotten more experience, we found that if you have a cut-off point, you actually get more done.

It was gangbusters, the whole thing. It was trying to make something that no one had ever done before in that format. It really worked, but we do have to thank Mutt Lange for that.

In what regard do you think you guys overdid it? Were you scrapping arrangement after arrangement? Were you doing take after take after take?

With the time, actually. You have this image in your head, and it was creating it for audio.

[Lange] always used to say, "Look, we've got to create Star Wars for the ears." And a song like "Rocket" literally was that. Even when we play it now, it's got such immense proportions, and we have this screen and all that stuff. You have this mental image, and you have this stacked-up vocal thing, which takes ages to do. Just singing them over and over, like Queen did.

We did that with the guitars as well. We made orchestrated guitar things, and not gratuitous. There's a big difference between just overdoing it and then doing it for a reason where it actually works and enhances the song; it always comes back down to the song.

Like I said, Mutt knew what he was doing, but back then, we were following his lead. It would be scrapping guitars and adding new parts and copying strings on a guitar with an EBow.

That reminds me of the Boston template, as per their debut album — a brainiac trying to create perfect, idealized rock songs — but it's an actual band with a producer.

About a year ago, I heard this BTS song and thought, "This actually sounds too good. It sounds almost like AI." I don't know whether it was or not.

I know these days a lot of writers will come in. There was this Beyoncé song where they said, "There's 23 writers!" and everything. And I get that. I really understand how that could be. You want to create the best that you can; you have a top-line guy that comes in, you have a drum programmer guy, you have someone writing the lyrics and all of that stuff.

We were kind of doing that back then with Mutt, but it was internal. It's like: OK, we need a melody. We've got this lyric; that works here. That was the approach, and I think it's a similar thing now.

With AI, I think that we are going to hear that. Like I said, I heard this BTS song and thought, This is so amazing. But could a person do that? I had my doubts. Maybe not. Perhaps it was a collective.

*Phil Collen performing with Def Leppard in 1983. Photo: Fryderyk Gabowicz/Picture Alliance via Getty Images*

With Drastic Symphonies on the way, how would you characterize the artistic and professional juncture that Def Leppard is at?

It's great. We're ticking every box. And a lot of these boxes we didn't quite tick in the '80s, when it was massive and we were selling sometimes a million records in a week, which is crazy, just the thought of it.

But there were still a few things that we didn't do. When we finally got into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, that kind of propelled us forward a little bit. Doing an album like this, but actually having a say in it and going, "We'll do it if we can do it this way."

We're actually doing the stadium tour now. We did one last year, which was great, with Mötley Crüe. We're still on tour with them and having such a blast. Grown-up kids at school together, just having that extreme thing.

Peter Frampton On Whether He'll Perform Live Again, Hanging With George Harrison & David Bowie And New Album Frampton Forgets the Words