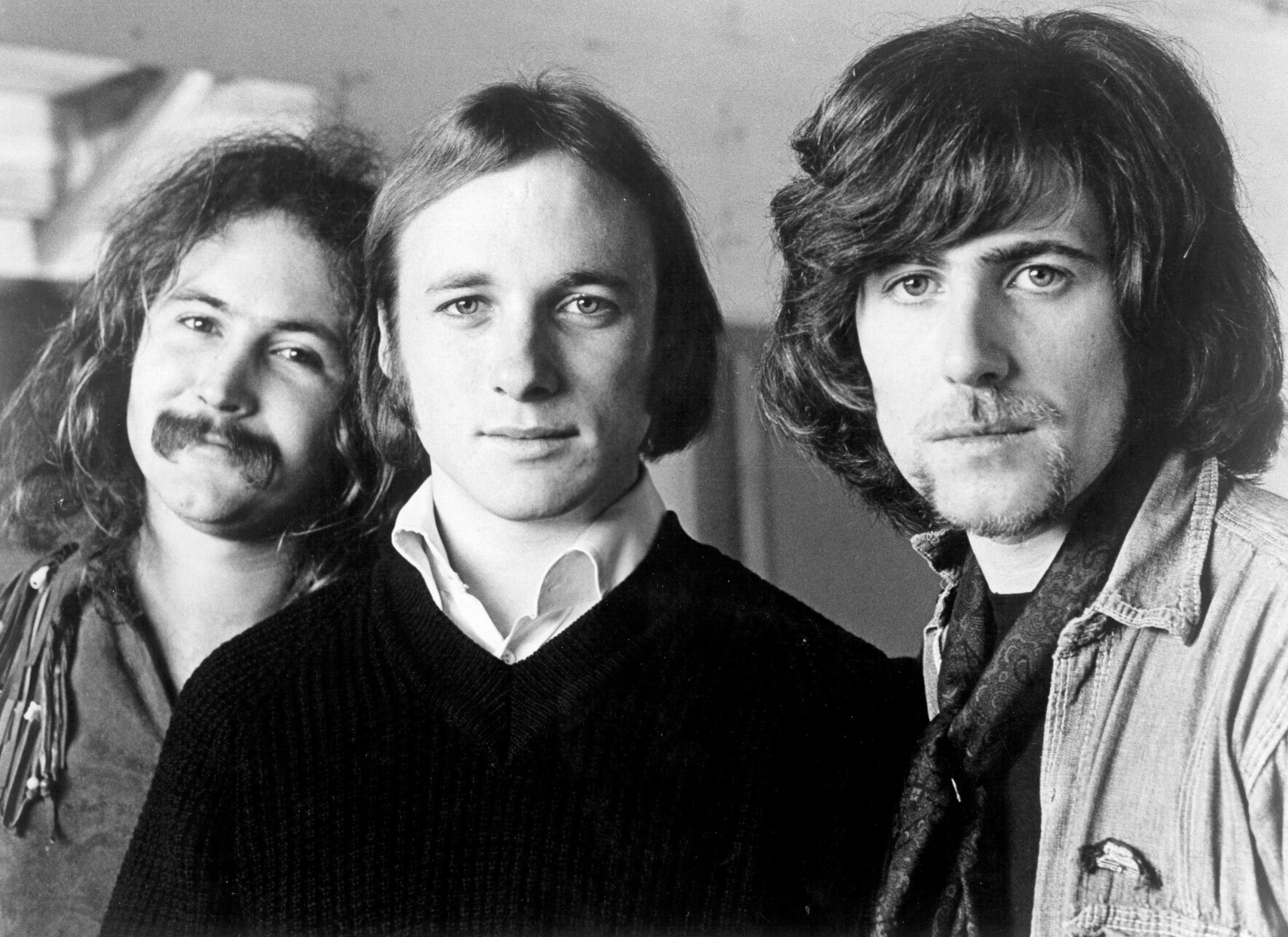

Photo: Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

list

5 Things You Didn't Know About 'Crosby, Stills & Nash'

Featuring classics including "Suite: Judy Blue Eyes," "Wooden Ships" and "Helplessly Hoping," Crosby, Stills and Nash's self-titled 1969 debut album is the ultimate entryway to the folk-rock supergroup. Here are five lesser-known facts about its making.

They'd been on ice since 2015, yet the death of David Crosby in 2023 forever broke up one of the greatest supergroups we'll ever know.

Which means Crosby, Stills & Nash's five-decade career is now capped; there's no reunion without that essential, democratic triangle. (Or quadrangle, when Neil Young was involved.) "This group is like juggling four bottles of nitroglycerine," Crosby once quipped. Replied Stephen Stills, "Yeah — if you drop one, everything goes up in smoke."

Looking back on that strange, turbulent, transcendent career, one fact leaps out: there's no better entryway to the group than their 1969 debut, Crosby, Stills & Nash, which turns 55 this year. Not even its gorgeous 1970 follow-up, Déjà Vu — which featured a few songs with one singer and not the others — their sublimation was about to blow apart, leaving shards to fitfully reassemble through the years. (The Stills-Young Band, anyone? How about the Crosby-Nash gigs?)

Pull out your dusty old LP of Crosby Stills & Nash, and look in the eyes of the three artists sitting on a beat-up couch in their s—kickers. The drugs weren't yet unmanageable; any real drama was years, or decades away. Do they see their infamous 1974 "doom tour"? The album cover with hot dogs on the moon? That discordant, Crosby-sabotaged "Silent Night" in front of the Obamas (which happened to be the trio's last public performance)?

At the time of their debut, the three radiated unity, harmony and boundless promise — and classic Crosby, Stills & Nash cuts like "Suite: Judy Blue Eyes" bottled it for our enjoyment forever. Here are five things you may not know about this bona fide folk-rock classic.

There Was Panic Over The Cover Photo

As silly as it seems today — nobody's going to visually mistake Crosby for Stills, or Stills for Nash — that the three were photographed out of order prompted a brief fire alarm.

"We were panicked about it: 'How could you have Crosby's name over Graham Nash?'" Ron Stone of the Geffen-Roberts company recalled in David Browne's indispensable book Crosby, Stills, Nash And Young: The Wild, Definitive Saga Of Rock's Definitive Supergroup. (The explanation: it was still in flux whether they were going to be "Stills, Crosby & Nash" instead.)

The trio actually returned to the site of the photograph to reshoot the cover, but by that time, that decrepit old house on Palm Avenue in West Hollywood had been torn down. (It's a parking lot today, in case you'd like to drag a sofa out there.)

It Could Have Been A Double Album

At one point during Crosby, Stills & Nash's gestation, the idea was floated to render it a double album — one acoustic, one electric.

"Stephen was pushing them to do a rock-and-roll record instead of a folk album because he was the electric guy," session drummer Dallas Taylor said, according to Browne's book. "He wanted to play." (Back in the Buffalo Springfield, Stills and Young would engage in string-popping guitar duels on songs like "Bluebird," foreshadowing Young's impending electric workouts with Crazy Horse.)

Happily, the finished product blended both the band's electric and acoustic impulses; rockers like "Long Time Gone" happily snuggled up to acoustic meditations like "Guinnevere" sans friction.

Famous Friends Were Soaking Up The Sessions

As Browne notes, there was a "no outsiders decree" as this exciting triangulation of Buffalo Springfield, Hollies and Byrds members was secretly forged.

But rock royalty was in and out: at one point, Atlantic Records co-founder Ahmet Ertegun rolled up in a limo with an "eerily quiet" Phil Spector. Joni Mitchell, Cass Elliott, and Judy Collins also turned up — and, yes, Judy Collins, Stills' recent ex, was the namesake for the epochal "Suite: Judy Blue Eyes."

"It started out as a long narrative poem about my relationship with Judy Collins," Stills said in 1991. "It poured out of me over many months and filled several notebooks." (The "Thursdays and Saturdays" line refers to her therapy visits. "Stephen didn't like therapy and New York," Collins said in the book, "and I was in both.")

"Long Time Gone" Almost Didn't Make It On The Album

Crosby's probing rocker "Long Time Gone" meant a lot to him. He'd less written than channeled it from the ether, immediately after the assassination of Robert F. Kennedy.

"It wasn't just about Bobby," he told Browne in the book. "He was the penultimate trigger. We lost John Kennedy and Martin Luther King, and then we lost Bobby. It was discouraging, to say the least. The song was very organic. I didn't plan it. It just came out that way."

It was always considered for Crosby, Stills & Nash, but it was proving hard to capture it in the studio. It might have died on the vine had Stills not sent Crosby and Nash home so he could work on the arrangement — which took an all-nighter to get right.

When he played the others his new arrangement, an exhilarated Crosby tossed back wine, and dove into the song "with a new, deeper tone," as Browne puts it — "almost as if he were underwater tone, almost as if he were underwater and struggling for air."

Ertegun Boosted The Voices — And Thank Goodness He Did

For all the prodigious, multilayered talent in Crosby, Stills & Nash, it's their voices that were at the forefront of their art — and should have always been.

However, the original mix had their voices relatively lower in the mix; Ertegun, correctly perceiving that their voices were the main attraction, ordered a remix, and thank goodness he did. The band initially pushed back, but as Stills admitted, "Ahmet signs our paychecks." As they say, the rest is history.

David Crosby On His New Album For Free & Why His Twitter Account Is Actually Joyful

Photo: David Redfern/Redferns

list

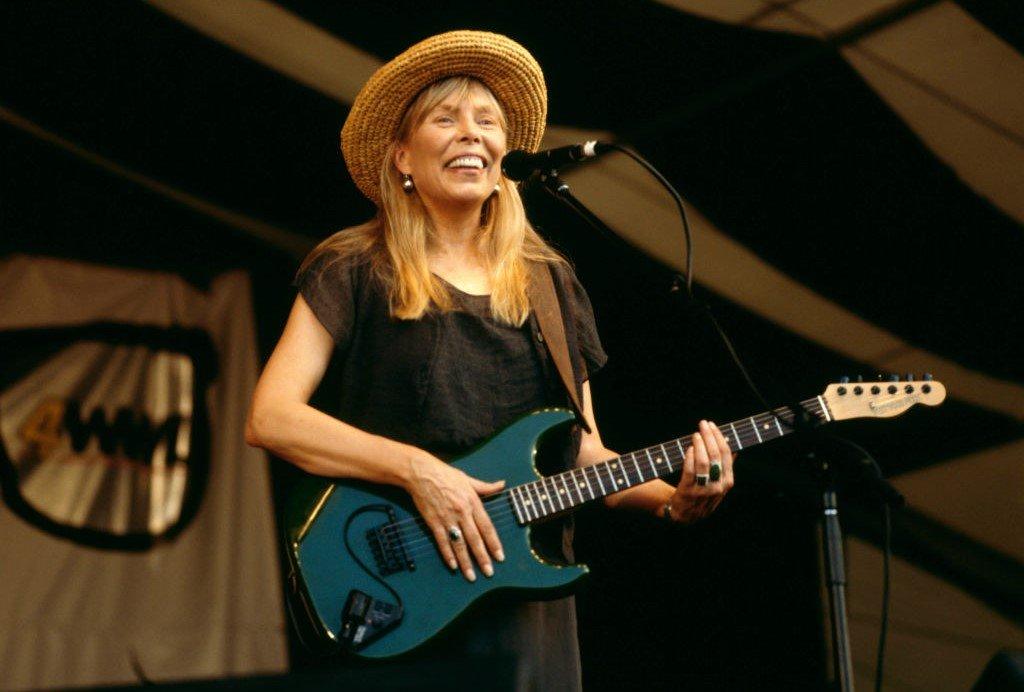

10 Lesser-Known Joni Mitchell Songs You Need To Hear

In celebration of Joni Mitchell's 80th birthday, here are 10 essential deep cuts from the nine-time GRAMMY winner and MusiCares Person Of The Year.

Having rebounded from a 2015 aneurysm, the nine-time GRAMMY winner and 17-time nominee has made a thrilling and inspiring return to the stage. Many of us have seen the images of Mitchell, enthroned in a mockup of her living room, exuding a regal air, clutching a wolf’s-head cane.

Again, this adulation is apt. But adulation can have a flattening effect, especially for those new to this colossal artist. At the MusiCares Person Of The Year event honoring Mitchell ahead of the 2022 GRAMMYs, concert curators Jon Batiste — and Mitchell ambassador Brandi Carlile — illustrated the breadth of her Miles Davis-esque trajectory, of innovation after innovation.

At the three-hour, star-studded bash, the audience got "The Circle Game" and "Big Yellow Taxi" and the other crowd pleasers. But there were also cuts from Hejira and Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter and Night Ride Home, and other dark horses. There were selections that even eluded this Mitchell fan’s knowledge, like "Urge for Going." Batiste and Carlile did their homework.

But what of the general listening public — do they grasp Mitchell’s multitudes like they might her male peers, like Bob Dylan? Is her album-by-album evolution to be poured over with care and nuance, or is she Blue to you?

Of course, everyone’s entitled to commune with the greats at their own pace. However, if you’re out to plumb Mitchell’s depths beyond a superficial level, her 80th birthday — which falls on Nov. 8 — is the perfect time to get to know this still-underrated singer/songwriter legend better. Here are 10 deeper Mitchell cuts to start that journey, into this woman of heart and mind.

"The Gallery" (Clouds, 1969)

Mitchell blew everyone’s minds when David Crosby discovered her in a small club in South Florida. Her 1968 debut, Song to a Seagull, contains key songs from that initial flashpoint, like "Michael from Mountains" and "The Dawntreader."

Mitchell’s artistic vision truly coalesced on her second album, Clouds. Although the production is a little wan and bare-boned, Clouds contains a handful of all-time classics, including "Chelsea Morning," "The Fiddle and the Drum" and the epochal "Both Sides, Now."

That said, "The Gallery," which kicks off side two, belongs at the top of the heap. There remain rumblings that it’s about Leonard Cohen. But whatever the case, Mitchell’s excoriating burst of a pretentious cad’s bubble ("And now you're flying back this way/ Like some lost homing pigeon/ They've monitored your brain, you say/ And changed you with religion") remains incisive, with a gorgeous melody to boot.

(And, it must be said: "That Song About the Midway," also found on Clouds, is a kiss-off to Croz, whom she enjoyed a fleeting fling with and a must-hear.)

"Cold Blue Steel and Sweet Fire" (For the Roses, 1972)

If you think you’ve got a grasp of Mitchell’s early talents, a new archival release proves they were more prodigious than you could imagine.

Joni Mitchell Archives, Vol. 3: The Asylum Years (1972-1975) kicks off with a solo version of "Cold Blue Steel and Sweet Fire." And as great as the studio version is, from 1972’s For the Roses, this version, from a session with Crosby and Graham Nash, arguably eats its lunch.

While Neil Young’s "The Needle and the Damage Done" has proved to be the epochal junkie-warning song of the 1970s, Mitchell’s song about the same subject easily goes toe to toe with it.

Images like "Pawn shops crisscrossed and padlocked/ Corridors spit on prayers and pleas" and "Red water in the bathroom sink/ Fever and the scum brown bowl" are quietly harrowing. Via Mitchell’s acoustic guitar, they’re underpinned by downcast, harmonically teeming blues.

"Sweet Bird" (The Hissing of Summer Lawns, 1975)

The Hissing of Summer Lawns is an unquestionable masterstroke of Mitchell’s fusion era.

Highlights are genuinely everywhere within Lawns — from the swinging and swaying "In France They Kiss on Main Street," to the Dr. Dre-predicting "The Jungle Line," to the title track, a hallucinatory lament for a trophy wife.

But amid these manifold high points, don’t miss "Sweet Bird," the penultimate track on The Hissing of Summer Lawns, tucked between "Harry’s House/Centerpiece" and "Shadows and Light."

"Give me some time/ I feel like I'm losing mine/ Out here on this horizon line," Mitchell sings through her dusky soprano, as the ECM-like atmosphere seems to whirl heavenward. "With the earth spinning/ And the sky forever rushing/ No one knows/ They can never get that close/ Guesses at most."

"A Strange Boy" (Hejira, 1976)

Much like The Hissing of Summer Lawns, Hejira — retroactively, and rightly, canonized as one of Mitchell’s very best albums — is nearly flawless from front to back.

The highs are so high — "Amelia," "Hejira," "Refuge of the Roads" — that almost-as-good tracks might slip through the cracks. "A Strange Boy," about an airline steward with Peter Pan syndrome she briefly linked with.

"He was psychologically astute and severely adolescent at the same time," Mitchell said later. "There was something seductive and charming about his childlike qualities, but I never harbored any illusions about him being my man. He was just a big kid in the end."

As "A Strange Boil" smolders and begins to catch flame, Mitchell delivers the clincher line: "I gave him clothes and jewelry/ I gave him my warm body/ I gave him power over me."

"Otis and Marlena" (Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter, 1977)

One of Mitchell’s most challenging and thorny albums, Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter is one of Mitchell’s least accessible offerings from her most expressionist era. (Mitchell in blackface on the cover, as a character named Art Nouveau, doesn’t exactly grease the wheels — to put it mildly.)

But across the sprawling and head-scratching tracklisting — which includes a seven-minute percussion interlude, in "The Tenth World" — are certain tunes that belong in the Mitchell time capsule.

One is "Otis and Marlena," one of the funniest and most evocative moments on an album full of strange wonders. Mitchell paints a picture of a cheap vacation scene, rife with "rented girls" and "the grand parades of cellulite" against a "neon-mercury vapor-stained Miami sky."

And the kicker of a chorus juxtaposes this dowdy Floridan outing with the realities up north, e.g. the 1977 Hanafi Siege: "They’ve come for fun and sun," MItchell sings, "while Muslims stick up Washington."

"A Chair in the Sky" (Mingus, 1979)

While Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter is rather glowering and unwelcoming, Mingus is a cracked, cubist realm that’s fully inhabitable.

Initially conceived as a collaboration between Mitchell and four-time GRAMMY nominee Charles Mingus, it ended up being a eulogy: Mingus died before the album could be completed.

Despite its lopsided nature — it contains five spoken-word "raps," as well as a true oddity in the eerie, braying "The Wolf That Lives in Lindsey" — Mingus remains rewarding almost 45 years later. And the Mingus-composed "A Chair in the Sky," with lyrics by Mitchell, is arguably its apogee.

Like the rest of Hejira, "A Chair in the Sky" features Jaco Pastorius and Wayne Shorter from Weather Report, as well as the one and only Herbie Hancock; this ethereal, ascendant track demonstrates the magic of when this phenomenal ensemble truly gels.

"Moon at the Window" (Wild Things Run Fast, 1982)

In Mitchell’s trajectory, Wild Things Run Fast represents the conclusion of her fusion phase, in favor of a more rock-driven sound — and, with it, the sunset of her second epoch.

Following Wild Things Run Fast would be 1985’s critically panned Dog Eat Dog and 1988’s even more assailed Chalk Mark in a Rain Storm. But for every arguable misstep, like the guitar-squealing "You Dream Flat Tires," there’s a baby that shouldn’t be thrown out with the bathwater.

One is "Chinese Cafe/Unchained Melody," another is "Ladies’ Man," and perhaps best of all is the luminous "Moon at the Window," where bassist/husband Larry Klein and Shorter wrap Mitchell’s sumptuous lyric, and melody, in spun gold.

"Passion Play (When All the Slaves Are Free)" (Night Ride Home, 1991)

At the dawn of the grunge era, Mitchell found her way back to her atmospheric best, with the gorgeously written, performed and produced Night Ride Home.

While its follow-up, Turbulent Indigo, won the GRAMMY for Best Pop Album (and is certainly worth savoring), Night Ride Home might have more to offer those who were enraptured by the majestic Hejira, and thirsted for a continuation of its aural universe.

The equally excellent "Come in From the Cold" is the one that has ended up on Mitchell setlists in the 2020s, but "Passion Play (When All the Slaves Are Free)" is even more transportive.

Despite the early 1900s sonics, "Passion Play" feels ageless and eternal, tapped into some Jungian collective unconscious as a wizened Mitchell posits, "Who’re you going to get to do your dirty work/ When all the slaves are free?"

"No Apologies" (Taming the Tiger, 1998)

If Night Ride Home sounds less played than conjured Taming the Tiger is like the steam that twists and disperses from its broiling, potent stew.

As much ambience pervaded Night Ride Home, Hejira and the like, Taming the Tiger is the only album in Mitchell’s estimable catalog to feel ambient.

Much of this is owed to Mitchell’s employment of the Roland VG-8 virtual guitar system, which allowed her to change her byzantine guitar tunings at the push of a button; the ensuing sound is a suggestion of a guitar, which enhances Taming the Tiger’s diaphanous and ephemeral feel.

"No Apologies" is something of a centerpiece, where Mitchell sings of war and a dilapidated homeland, sailing forth on a cloud of Greg Liestz’s sonorous lap steel.

"Bad Dreams" (Shine, 2007)

Mitchell has always cast a jaundiced eye at the music industry machine, so it’s no wonder she hasn’t released a new album in 16 years. (Although, as she revealed to Rolling Stone, she’s eyeing a small-ensemble album of standards with her old mates in the jazz scene.)

But if Shine ends up being her swan song, it’d be a fine farewell. "Bad Dreams" — written around a quote from Mitchell’s 3-year-old grandson: "Bad dreams are good / In the great plan" — is impossibly moving.

Therein, Mitchell considers an Edenic tableau as opposed to our modern world, where "these lesions once were lakes." Movingly, the song’s final lines accept reality for what it is ("Who will come to save the day? / Mighty Mouse? Superman?") rather than what she wishes it could be.

With that, Mitchell’s studio discography — as we know it today — reaches its conclusion. But although the artist is only fully getting her flowers today, we’ve only scratched the surface of the gifts she’s bestowed upon us.

Living Legends: Judy Collins On Cats, Joni Mitchell & Spellbound, Her First Album Of All-Original Material

Photo: Burak Cingi/Redferns

list

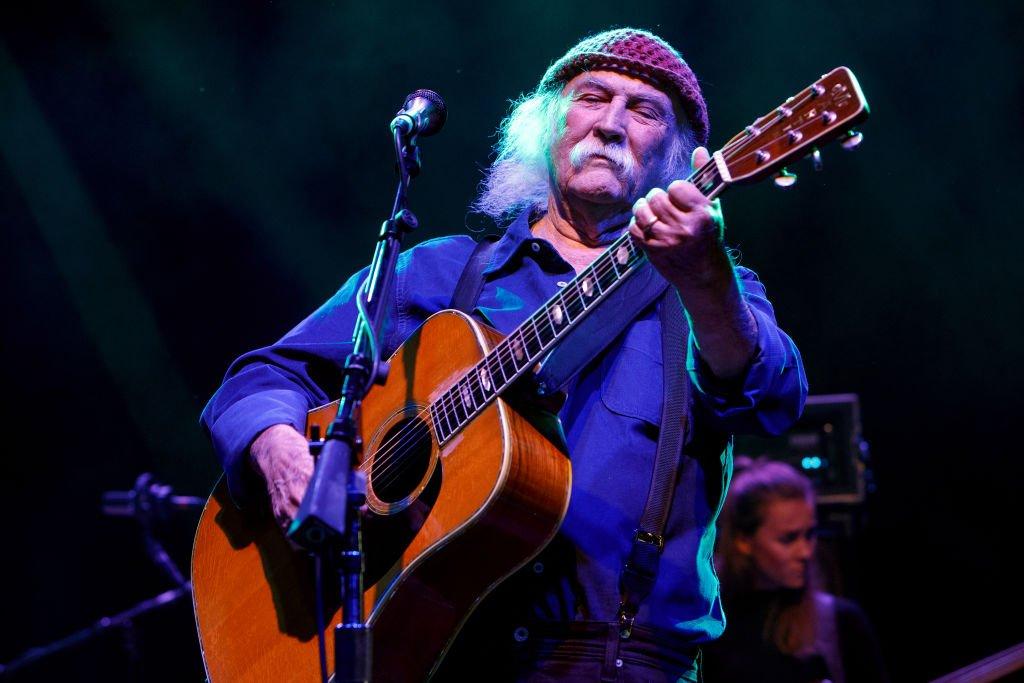

Remembering David Crosby: 5 Tracks That Define The Rock Storyteller's Thoughtful Craft & Social Commentary

Rock icon David Crosby passed away Jan. 19 at age 81. His discography, like his reputation, is an immense and disparate jaunt that doubles as a music history lesson.

David Crosby was a 1960s folk-rock star, a '70s singer-songwriter marvel and a contemporary creative who simply couldn’t stop churning out new music. Crosby died on Jan. 19 at the age of 81, leaving the world with a massive body of work that helped shape multiple generations. Many rightfully remember him as a rock icon.

"GRAMMY Award winner and 10-time nominee David Crosby left an indelible mark on the music community and the world," said Recording Academy CEO Harvey Mason, jr. "As a co-founder of legendary groups the Byrds and Crosby, Stills & Nash, he created some of the most influential rock music in his multi-decade career. His incredible legacy will be remembered forever, and our thoughts are with his fans and loved ones during this difficult time."

Crosby has multiple entries in the GRAMMY Hall of Fame, though his only GRAMMY win came in 1970 with a Best New Artist golden gramophone for his work with Crosby, Stills & Nash. (He was nominated for the same award in 1966 for his work with the Byrds.) Crosby's most recent nomination at the 62nd GRAMMY Awards for his 2019 documentary, Remember My Name.

In a Facebook post, Graham Nash recalled the "pure joy of the music we created together, the sound we discovered with one another, and the deep friendship we shared. David was fearless in life and in music." Neil Young echoed that sentiment in a statement, reflecting on how Crosby's "voice and energy were at the heart of our band. His great songs stood for what we believed in and it was always fun and exciting when we got to play together."

Crosby’s discography, like his reputation, is an immense and disparate jaunt that doubles as a lesson in music history. From his most recent slate of solo singles — which dabbled in folk and jazz — to his groovy work with the Byrds that made him famous, and his sometimes tumultuous collaborations with Stephen Stills, Nash and Young, here are five essential tracks that paint an aural picture of the music legend.

"Turn! Turn! Turn!" (1965)

Crosby helped concoct this anthem while a member of folk-rock group the Byrds, and it's difficult to imagine protests, happenings and fashion of the hippie generation without hearing "Turn! Turn! Turn!"

Folk heavyweight Pete Seeger borrowed the bulk of the lyrics from the Bible's Book of Ecclesiastes, though the Byrds made the song a hit. Crosby's rhythm guitar and backing vocals give the song a mystical quality (along with Roger McGuinn’s 12 string Rickenbacker, of course). Synonymous with the activism that engulfed the conflict in Vietnam, "Turn! Turn! Turn! went to No. 1 just as that war in Southeast Asia was at the top of public consciousness.

"Guinnevere" (1969)

Written by Crosby for Crosby, Stills & Nash's self-titled debut album, the tender, heart-wrenching "Guinnevere" tells the story of three women — among them, a girlfriend he lost in a car accident — opening with the plaintive, "Guinnevere had green eyes" before transitioning into a haunting line: "She shall be free."

Subsequently covered by Miles Davis on The Complete Bitches Brew Sessions, a live version of "Guinnevere" was also one of the very last songs Crosby released. Speaking to Music Radar, Crosby said the torch song "could be his best" — quite a statement, considering the scope of his mighty career.

"Almost Cut My Hair" (1970)

Crosby wrote this irreverent yet poignant ode to the counterculture for Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young's Déjà vu. The song takes Crosby’s famously stubborn nature and transposes it to the fading days of the hippie movement, long hair and all.

"If you’re writing a song like 'Almost Cut My Hair,'" Crosby said in his final interview, just two weeks before his death, "[And it’s] something where you feel like you have a point to make, then that anger can come in there but you’ve got to be careful with that s—." Aside from the of-the-moment lyrics (in which he proclaims he feels like letting his "freak flag fly"), Crosby takes center stage musically. His voice is the only one heard, as Still, Nash and Young pitch in on instrumentation.

"Cowboy Movie" (1971)

Foreshadowing his future career, Crosby was deep in his collaboration with CSNY when he released his debut solo album If I Can Only Remember My Name. Featuring friends such as Joni Mitchell, and members of Santana and the Grateful Dead (they called their band the the Planet Earth Rock and Roll Orchestra), the album was maligned upon its release but has been reassessed to acclaim.

"Cowboy Movie," with the Dead’s Jerry Garcia and Phil Lesh on guitar and bass, is a tribute to the tales of the Old West. "Now I'm dying here in Albuquerque," Crosby sings as the song comes to a close. "I must be the sorriest sight you ever saw."

"She’s Got to Be Somewhere" (2017)

"Whatever time I have left on this planet should be dedicated to making the best music I can," Crosby said in 2018 "It’s the one contribution I can make. Music helps things; it makes things better." Crosby did just that, going on a creative tear where he released a bevy of solo albums.

On 2017's Sky Trails, the man who helped pioneer folk and psychedelic rock is almost unrecognizable. The cool and crackling "She’s Got To Be Somewhere," a co-production between Crosby and his adopted son James Raymond, is an exploration of jazz fusion. "It’s ingrained in me and it’s ingrained in my son James," Crosby said of his jazz influences during a 2019 conversation with Jazz Times, citing jazz titans Dave Brubeck, Chet Baker, Gerry Mulligan and Bill Evans.

David Crosby On His New Album 'For Free' & Why His Twitter Account Is Actually Joyful

Photo: Michael Ochs Archive

video

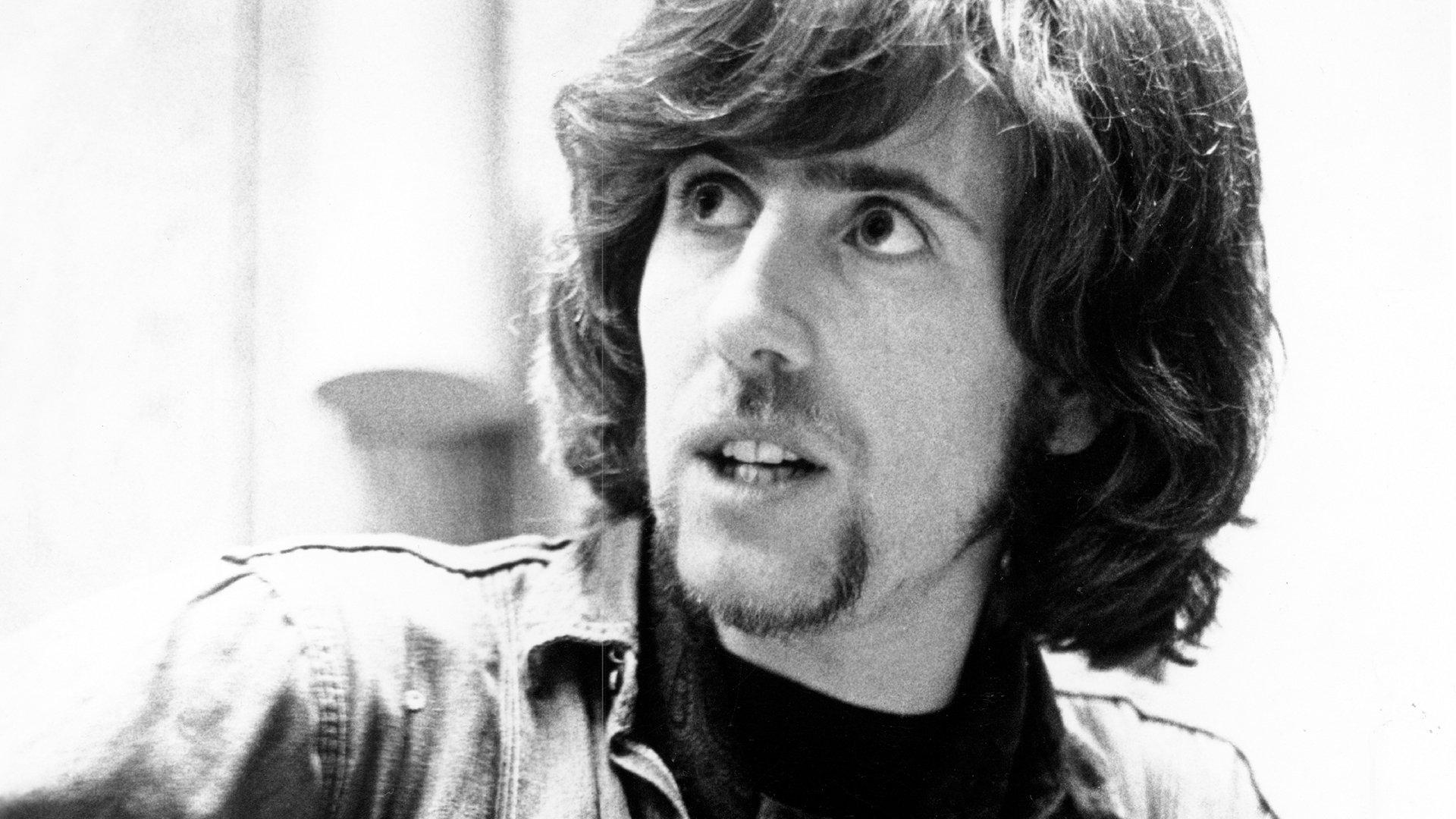

Sound Bites: Graham Nash Reveals How Joni Mitchell Helped Form Supergroup Crosby, Stills & Nash

The other members of Crosby, Stills & Nash might have different stories about how the supergroup became a band, but if you ask Graham Nash, it all dates back to a party at Joni Mitchell's house.

All-star folk rock group Crosby, Stills & Nash became a band when its three members — David Crosby, Stephen Stills and Graham Nash — all found themselves free agents after parting ways with their respective bands. Crosby had been asked to leave the Byrds, Stills was a solo act after Buffalo Springfield broke up, and Nash had left the Hollies — which made the timing perfect for the three artists to come together and form something new.

The three bandmates might remember three different stories, but if you ask Nash, it all began in 1968 with a party at Joni Mitchell's house. He shares the full story in this episode of Sound Bites, remembering that fateful night in a video interview pulled from the GRAMMY archives.

"I took a cab from the airport to 8217 Lookout Mountain, which is where Joni's house was," Nash begins. "And I heard people talking."

He was disappointed, as he'd been hoping to be alone with Mitchell, but walked in to find the aftermath of a dinner party she was having with Stills and Crosby. As he remembers, the four of them "smoked a big one" before Crosby suggested that he and Stills play a song they'd been working on for the room. That song, which Stills had recently written, was "You Don't Have to Cry."

"They got to the end of it, and I said, 'Wow. Well, first of all, it's an incredible song,'" Nash recalls. "...I said, 'Sing it again for me.' They looked at each other, and they shrugged, and they sang it again. And they got to the end of that, the second time, and I said, 'Okay, I think I got it.'"

When they sang it a third time, Nash came in with vocal harmonies. "We got about a minute into it and we had to stop and start laughing, because it was silly. I mean, we were all pretty big fans of harmony, and we've played a lot in our lives, but this was something different. When David and Stephen and I sing well together, it's something else."

That song, and that special vocal harmony, laid the foundation for Crosby, Stills & Nash's career. "You Don't Have to Cry" appeared on their first, self-titled album in 1969, and the following year, it helped them win a GRAMMY Award for Best New Artist.

Press play on the video above to hear Nash's version of how the band's formation all went down — though "Stephen has a different story," he quips — and keep checking GRAMMY.com for more episodes of Sound Bites.

Songbook: How Bruce Springsteen's Portraits Of America Became Sounds Of Hope During Confusing Times

.jpg)

Photo: Barry Feinstein Photography, Inc.

interview

Living Legends: Roger McGuinn On The History Of The Byrds, His One-Man Show And Editing His Own Wikipedia Page

At 80, the former Byrds leader remains as curious as ever — puttering with gadgets, learning obscure folk songs, and playing songs and telling stories on the road. A new, photo-stuffed coffee-table book illuminates his early history like never before.

Living Legends is a series that spotlights icons in music still going strong today. This week, GRAMMY.com spoke with Roger McGuinn, a founding member of the Byrds and folk-rock pioneer who, at 80, remains active as a solo act. A new coffee-table book about the early history of the band, The Byrds: 1964-1967, is available now.

Roger McGuinn is still tinkering.

Decades ago, he helped codify the Rickenbacker 360/12 as a rock 'n' roll armament. He electrified his beloved folk music to make it jangle and chime. He wrote immortal odes to celestial voyages and alternate dimensions, and threw down incendiary "out" solos that would make John Coltrane proud. And that maximum-curious mind is still humming.

This is wholly apparent in his one-man show currently criss-crossing the East Coast. Therein, the 80-year-old former Byrd clarifies, contextualizes and canonizes his life story, perhaps working it out for himself just as much as he is for his audiences.

And as far as the folk canon that galvanized and mobilized him in the first place, he's far from finished with his decades-long analysis. On his website, he releases free-to-download interpretations of songs from the folk, gospel, sea-shanty, and calypso traditions, among others — under the umbrella of his "Folk Den Project."

On top of that, he remains a lifelong enthusiast for all things engineering, aviation, gadgets and science fiction. From the road, McGuinn explains that his engineer grandfather got him interested in all things that light up and whir.

"I take LEDs and put them in a little box with a switch on it and make them blink, just for fun," he tells GRAMMY.com. "I love taking things apart and trying to put them back together."

Fortunately for all of us, McGuinn isn't all that different from the man we learn about in The Byrds: 1964-1967, a lavish new coffee-table book that hit shelves on Sept. 20.

Featuring 400 pages of more than 500 illuminating photographs and an oral history courtesy of surviving Byrds McGuinn, Chris Hillman and David Crosby, the book is a definitive account of the band's genesis, commercial breakthroughs with "Mr. Tambourine Man" and "Turn! Turn! Turn!" and on-ramp to their eventual plunge into psychedelia.

In his post-Byrds life, McGuinn deepened in profound ways — not only in diving deeper into the folk tradition and honing his storytelling acumen, but focusing on his Christian ministry alongside his wife, Camilla. These days, he may have little interest in getting the old band back together, but he arguably remains their most active and public custodian — one one-man show at a time.

Read on for a history-spanning interview with the three-time GRAMMY nominee about the new book, his folkie origins, how he picked up the Rickenbacker, the importance of Gene Clark and Clarence White, and myriad other Byrdsy subjects.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

Before we time-warp to 55 years ago, I think it's important to lead with a question about your life and work today. What's creatively percolating for you?

Well, I've been touring since [hesitates, chuckles] 1960! I'm still doing it at 80 years old. We're on a tour right now. We're going to play a theater in Brattleboro tomorrow night. I think it's a month-long tour; it's going to take us around to Easton. So, that's one thing.

When I'm home, I record; I've got a Folk Den Project that I do every month; I record a song and put it on the internet for a free download, in a section called The Folk Den on my website, McGuinn.com. It's a public service sponsored by UNC Chapel Hill.

I record other things. We've recorded CDs, but CDs are kind of a dying breed, so we've had to find some other way. The streaming thing is working out well.

For people who may know the Byrds, since they've been in the ether for so long, but haven't caught you live, what can they expect from you in performance?

I do a one-man show. I do, like, the life of Will Rogers, except it's not about Will Rogers; it's about me. [Chuckles.] I tell the story about how I was inspired early on in my teens to get a guitar; I played guitar in the Old Town School for Folk Music and got hired by the Limeliters and the Chad Mitchell Trio. [I played with] Bobby Darin and Judy Collins and became a studio musician and writer at the Brill Building in New York.

Tell me how The Byrds: 1964-1967 came to be. Why did it feel appropriate to tell the story of the band's early history mostly through photographs, with an oral history threaded through them?

I wasn't really on the inside of this, but Chris Hillman did an autobiography a couple of years ago for BMG Publishing. They acquired a number of photographs of the Byrds, and I guess they had so many, they couldn't use them all.

So, they said, "What are we going to do with these?" They decided to make a coffee-table book — 400 pages, 500 photos, printed with Italian paper. It's beautiful; it's a gorgeous edition.

Before we dig into this era of the band reflected in its pages, can you tell me about your early love of all things related to technology, outer space and sci-fi? To me, that's one of the most captivating facets of the band — that sense of far-out curiosity, that futuristic bent.

Well, I got into it when I was living in Chicago. My grandfather had been an engineer for the Deering Company or something — I'm not sure of the company — but he was instrumental in building bridges over the Chicago River.

He was always in engineering, and he used to take me to the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago every Sunday. That's where I developed my love of technology. I'd push buttons, things would light up and whir, and I'd go, "Wow! That's cool!"

That's where it all came from. I've just got a little bit of engineering in my blood.

Are you still a tinkerer to this day?

Oh, yeah. Absolutely. I love taking things apart and trying to put them back together. [Chuckles.] Building little things. It's a lifelong hobby.

*The Byrds in Chicago, 1965. Photo: Jim Dickson Archive, courtesy of Henry Diltz Photography*

This coffee-table book goes pretty deep into the band's synthesis of influences, from folk music to the Beatles. But I'm most interested in how the Byrds were almost predicated on a single instrument; that's a rare concept. What attracted you to the bell-like sound of the Rickenbacker so early on?

I was a 12-string player back in the folk days. I got my first 12-string guitar in Chicago in 1957; I believe it was a Regal 12-string. I was interested in the 12-string because of Lead Belly and Pete Seeger and Bob Gibson, who was kind of an acolyte of Pete Seeger.

When I was a studio musician in New York, I was the go-to guy for acoustic 12-string for a lot of folk acts. I was the musical director on Judy Collins' third album [1963's Judy Collins #3]; I played on the demo of "The Sound of Silence" for Paul Simon. The Irish Rovers, a lot of folk acts.

So, I was already a 12-string player, and when the Beatles came out, I was enthralled with [them] because they were using folk-music chords in their rock 'n' roll. I noticed that George Harrison had a Rickenbacker electric 12-string, and I'd never seen one of those before. It was a new instrument at the time; in fact, his was only the second one ever made. The first one went to somebody named Suzi [Arden], who was in a group in Las Vegas, doing lounge acts.

When I found out about the Rickenbacker electric 12-string, I went to a music store and traded in my acoustic 12-string that Bobby Darin had given me and a five-string, long-necked banjo — a Pete Seeger style — and I got the Rickenbacker electric 12.

It was just such a great-sounding instrument. I played it eight hours a day!

*Roger McGuinn performing with the Byrds in 1965. Photo: Barry Feinstein Photography*

I don't think most people grasp how much of a pressure cooker the mid-1960s pop market was like; we hear stories about the Beatles needing to rush out Rubber Soul by Christmas, and so forth. The Turn! Turn! Turn! album came out only six months after Mr. Tambourine Man. Did you guys feel that crunch, that market demand?

We had a contract with Columbia where we had to do an album every six months, so it really did put the pressure on. We came out of the box with a No. 1 hit, and we had to live up to that. Fortunately, "Turn! Turn! Turn!" became a No. 1 as well.

It was a lot of pressure. We had Gene Clark as the main writer; he was doing great. Then, when he left, it was more difficult to come up with enough material for a good album. Every six months — that was part of the contract.

Gene is often framed as the tragic figure of the band, but The Byrds: 1964-1967 lays out what a force he was; he was the most prolific writer in the band. How would you describe his role in the creative machinery early on?

Well, he was obviously the main songwriter. He and I started the group; we started writing songs together, and he and I wrote some songs. Then, Crosby came along, and he wasn't really writing songs at that point.

We were doing some outside material, like Dylan and Seeger, and Gene kept writing every day. He must have written 30 songs a month; some of them were really good, so we ended up using those.

Read More: David Crosby On His New Album For Free & Why His Twitter Account Is Actually Joyful

*The Byrds in Beverly Hills, 1965. Photo: Jim Dickson Archive, courtesy of Henry Diltz Photography*

**The book closes right at that jumping-off point into 1968's The Notorious Byrd Brothers, which means we go deep on that delicious transitional period, with songs like "5D" and your cover of Dylan's "My Back Pages." Those are probably my two favorite Byrds tracks; can you share any memories regarding them?**

"5D": I wrote that while I'd been reading a little book called 1, 2, 3, 4, More, More, More, More [by Don Landis]. It was about multiple dimensions — kind of like string theory, or something. I thought that'd be an interesting subject for a song.

"My Back Pages": Jim Dickson had been the Byrds' manager, and we'd fired him. One day, I was in L.A., driving up La Cienega, and came to a stoplight, and Dickson pulled up next to me and rolled down the window. He said, "Hey, Jim!" — that was me — "You guys ought to record Dylan's 'My Back Pages!'"

I said, "Thank you." It had been a while since the Byrds had a Top 20 hit. So, I went home, got the record out, and listened to the song. It was in 3/4 time, and I had to rearrange it for rock 'n' roll. So, I did, and it became — I think it was No. 22. I'm not sure. [Writer's note: The song peaked at No. 30 on the Billboard Hot 100.]

I feel like "5D" fell into that space where, for decades, people presumed it was about drugs. No such thing: it's the product of a curious mind, which you still possess.

Exactly. It was more of a spiritual thing than a drug thing.

**A lot of people don't grasp how incredible, in my opinion, the band remained in the late '60s and early '70s after so many lineup changes; just recently, I was wigging out to the 16-minute live version of "Eight Miles High" on 1970's (Untitled). What do you remember of this time? Are these happy memories for you?**

Well, [Byrds guitarist and mandolinist] Clarence White and I were good friends, and we loved playing together. He was probably the best guitar player we ever had. It was like having Jimi Hendrix or Eric Clapton in your band, or something.

I remember one time at the Whisky, Jimi Hendrix came backstage, and he went running right over to Clarence and shook his hand. The first time we played at Fillmore East with Clarence and the band, there was a big difference between the way it had been with the audience reaction [and the way it was then].

The audience was used to a certain level of Byrds musicianship, and when Clarence came out there, he just slayed them. He was just incredible.

We lost Clarence too young, just like Gene. What was it like to have those guys in the room?

Well, they didn't hang out in the same room. [Chuckles.]

I know — separately, I mean!

Clarence and I hung out more than Gene and I did. Gene was kind of off to himself; he had his life. But Clarence and I were on the road together, and we'd hang out more. Clarence was just a really nice guy and a brilliant guitar player.

What misconceptions still float around regarding the Byrds and your role therein that you'd like to correct, if any?

Oh, I don't really need to fix history. I tried that once on Wikipedia. Somebody put out some stuff on there that wasn't correct, so I went on Wikipedia and corrected it. And they banned me, because some 15-year-old kid in Canada had changed it!

Oh my gosh. Do you remember what the falsehood was?

I think it had something to do with the Subud religion. I'm not sure. [Writer's note: McGuinn changed his name from Jim to Roger in 1967 during a period of experimentation with Subud.]

[McGuinn's wife, Camilla, interjects in the background.] Oh! I forgot that. My wife says I had friends who went on and corrected it for me.

That's good to hear. The historical record can become distorted. A lie travels around the world before the truth is still putting on its shoes, as they say.

Right, we've heard that saying. I think Henry Ford said, "History is bunk."

Robby Krieger's Memoir Set The Night On Fire Offers A New Perspective On The Doors & Jim Morrison: "There Was Another Side To Him"